As someone who’s written several times (here and here) about the course of modern health care (its inherent complexity and cost), I’ve been watching the latest moves in US health care funding with a great deal of interest.

From the introduction of antibiotics to the breakthroughs in transplant surgery, medicine in the 20th century was in a position to provide dramatic improvements in health care (both quality of life and length of life) at relatively modest cost. Many consider it a golden age in medicine. My personal belief is that medical care is about to hit another burst of creativity and success (but at much higher cost-to-benefit) as non-invasive imaging, micro-surgery, diagnostic testing, and DNA-propelled pharmaceutical customizations kick in. I may be wrong, but I think my beliefs are a reasonable extrapolation of the trends in medical care since the end of the 1970s “silver bullet” period of medicine.

So what do my guesses about modern medicine mean in a new era of greater tax subsidies for US health care? An era which, by necessity, must politicize health care further. It got me to thinking about the hidden subsidies during earlier periods of American history, powered by the domestic political systems of the time, and driven by citizen/voter appetites. And it got me thinking about the law of unintended consequences.

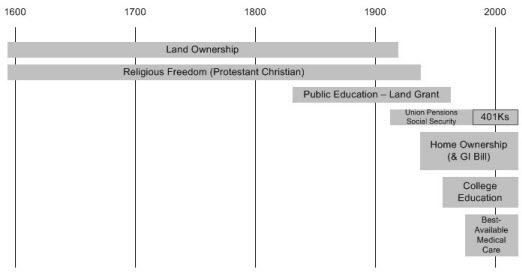

After a few minutes scribbling on the back of an envelope, I came up with the following:

I’m hardly an historian nor an expert but l think the diagram above identifies at least some powerful appetites in American society that were supported and encouraged by political powers at the time. Appetite begat political response. Politics generated subsidies. Subsidies generated yet more appetite. A first American subsidy, even before political freedom, was obviously economic opportunity … which in a pre-industrial society translates into land ownership. Away from European cities and epidemics, early Americans had few limits on their ability to clear and thereby own the land which they settled. Force of arms would remove the land from Native American or Spanish/French control. High reproductive rates and greater life expectancy created a dramatic increase in the number of Americans who also desired their own property. The laws in place, and the decisions of authorities, supported the development of squatting and land purchase which built up its own momentum in the 18th and 19th centuries … defying both British imperial preference (to keep the colonies east of the Appalachians) and the hostility of Native Americans to the methodical conversion of their land from hunting/gathering/subsistence agriculture, to the newly vibrant agricultural practices of the English-speaking world. Every phase of economic development … agricultural equipment and railways … drove further expansion of land development. As late as World War 2, land clearing for agriculture was still underway up North. 350 years.

In partnership with the desire for land was the desire to escape the religious conflicts of the European continent. For Protestant Christians, members of a constantly shifting kaleidoscope of sects and denominations, the development of laws and political traditions that would provide them with freedom of worship were important … and sustained a suspicion of clerical central authority that lasted well into the 20th century. Laws and political traditions responded accordingly. The concept of religious exemptions encouraged churches to acquire their own economic assets.

As part of that religious tradition, dating back at least to the late 16th century, literacy and education were encouraged and seen as an important part of full participation in both religion and society. As time went by, public funds took over from religious organizations in the sponsorship and maintenance of primary and secondary education. Schools were important, and worthy of parental supervision and participation whether on the frontier or in the city. The provision of schooling was therefore a significant political concern as well. The “Land Grant” educational Acts of the late 19th century were a major commitment of funds to the parts of America that were still being settled. The development of these educational institutions was to carry the western part of the country through the transition from predominantly agriculture and resource-extraction, to industrialization and the modern service economy.

As industrialization took hold, and the farms were emptied in the early 20th century … the “hired hands” who once aspired to land ownership were now workers in factories, mines, and urban industries. A new demand for safety and collective bargaining for wages was matched by a burst of laws and regulations governing the formation of unions and the status of labor. The idea of a pension income after a lifetime of service to a company became commonplace. Social Security in the 1930s reflected a new concern that some regions of the country, and some families, were simply unable to provide sustenance for the very elderly. The definitions of “sustenance” and “elderly” were to broaden in following decades. In latter days, we’ve seen a further subsidy of financial arrangements as individuals have become responsible for their own pension schemes (401Ks) and a constellation of laws have made retail investing (and the associated services) a going concern.

Soon after 20th century unionization had changed the terms of work, the workplace, and “retirement,” a new benefit was encouraged by law, tradition, and government … reflecting the aspirations of a newly prosperous and newly urbanized population … home ownership. And thus for many years, the tax regulations, laws, and financial instruments of the United States have leaned heavily toward subsidizing home ownership. Sometimes those subsidies have been generous to the point of silliness (the so-called NINJA loans).

In the post-war era, a college or vocational education changed from being a rare opportunity to an expectation, almost a right. Through direct and indirect subsidies, governments encouraged the expansion of post-secondary education. Educational institutions became non-profit engines of growth … fueled by industrial and government subsidies, and tuition that outpaced inflation. Educational quality now became a distinguishing feature in pricing. The assumption of personal debt in the pursuit of a college or university degree was widely considered reasonable. Certainly the income of college graduates seems to have held up far better in the latter half of the 20th century than that of agricultural and industrial workers.

And finally, health care … and the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-Sixties, which first subsidized health care for citizens during what I’ve proposed was a unique “golden age” of medicine. These programs have since grown like Topsy, to the point that they are woefully underfunded. As we know from the heated discussions surrounding the latest debates on tax-supported health care, the hidden penalties placed on the public health care system to provide emergency room care to all comers, and Medicare treatment at less than cost, has led to the disappearance of many non-profit health care organizations. Someone has to pay. Non-profit can’t be “negative-profit” for long. Either the taxpayer, or the health care plan purchaser, or the company health care plan (and therefore corporate customer) has to pony up. Of course, we’ve seen there’s another option: … make the next couple of generations of citizens pay for current consumption.

Reflecting on four centuries of political subsidies in America, it seems to me that sustainability only comes if the populace is willing to drop some subsidies in order to gain new ones. Land ownership (forty acres, and a mule) gave way to salary work. Not without resistance, mind you. Religious freedom gave way to religious indifference and the dwindling of denominational political power. The union pension (and associated “Cadillac” health care plans) are now limited to government employees and the aging members of dying industries.

Unfortunately, as the diagram above indicates, that still leaves the US with a very full plate of political subsidies to squeeze out of the electorate, and the electorate’s kids and grand-kids.

To make a long story short, then,

* if medical care is about to get more and more expensive (because there’s just more of it), and

* if good medical care and great medical care are more easily distinguished, courtesy of the Internet

Price-pressure on the very best care will be relentless. How many politically subsidized aspirations can the nation support then? How much room is there on that American subsidy plate?

“Retirement”

“Home ownership”

“College education”

“Medicare/Medicaid”

All have been subsidized by past US prosperity, leading to unsustainable “bubble” demand and pricing in the last forty years. Retirements that start too soon and last too long. Home ownership (why not a cottage as well!) far beyond physical need. College education inflated in cost and reputation by self-perpetuating bureaucracies rather than employment requirements. Unfunded liabilities for the medical care of millions of poor Americans, run as a giant Ponzi scheme with the hope that kicking the can down the road will solve the problem on someone else’s watch. Expectations have been established. But which of these cultural expectations and political subsidies will fall away first? In the words of the wise-ass market pundits, “you can make it hop but you can’t make it fly!” You can run up the credit card to pay for the subsidies but eventually the bill comes due.

Having just added a massive set of subsidies in the domestic economy for a service (medical care) that is enhanced by basic scientific and industrial research (and by the inherent frailty of the human form!), I think America has placed its chips on the next big “bubble” … maybe the last big bubble … in human appetite. As one Internet commentator noted … do you really have something better to spend you money on than your health? Not something more preferable but something better. What dream will you give up in order to add a new one to the American subsidy story?

Just as our parents and grand-parents no longer expected to have their own farm, and we gave up trading 35 years of our life for a union pension, we’re going to have to start talking to our kids about what we’re going to give up to get this new health care dream, as and when and how we need it. For everyone in the American boat, legal or not. With the vision of “best possible care” all too visible before us, like foreign vacations, McMansions, and Harvard degrees.

Interesting times ahead.

I’m not sure I’d agree that all of those are/were subsidized. Perhaps you’re using the term *very* broadly. I suppose one could argue that the mortgage interest deduction is a subsidy and perhaps the 401K by the same reasoning… (though I’m leery of treating tax deductions as subsidies it smacks of thinking all of our income belongs to the gov until they give it back) but how do you get union pensions and university educations as subsidized?

If the claim is that the unions and the universities are being subsidized rather than individuals I guess that’s possible, but it’s rather a different kind of case. As one who paid way too much of my very hard earned money for a degree of dubious worth, I find the idea that the university may have been taking money from the feds too not at all encouraging. To put it another way, it seems unlikely that a university successfully seeking favors or handouts from the government has any substantial effect on their charging students whatever the market will bear.

And religious freedom? You completely lost me on that one as a subsidy, unless again you’re stipulating that not only our money buy our consciences belong to the gov until returned to us in fief.

fwiw.

@ John, “charging students whatever the market will bear”: won’t what the market bears be dependent on a student loan system? So won’t that system result in lots of cash for the university administrators to splash?

Yes, there’s something in that. I’d forgotten about the student loan angle. I knew people who had government backed student loans. In my experience they were mostly kind of a joke, but I hear they’ve been changing the system.

Come to think of it, I had a thing called a Pell grant. So I’ll concede the point, but with the observation that it’s hardly giving them a lot of money to splash around, some yes, but I doubt that co-signing for some loans and making small grants in a few cases is a very substantial contribution to inflating tuition rates. My Pell grant paid for somewhere around 5% of my tuition expenses not counting all the other expenses.

So, while I’ll concede an effect from student loans, and a slightly larger one from Pell grants, they can’t amount to very much on the scale of enormous increases in college expenses. I blame irrational exuberance. I think a whole generation of parents raised their kids to believe that a college education was a ticket to financial success which created a crazy bidding war and drove prices to incredible levels. I think there was a false perception of *very* high value in the product which caused prices to rise to the levels commensurate with that value.

John,

We subsidize religion by giving them tax credits that a normal organization can’t obtain.

As far as education, it’s a mixed bag. Some schools are highly subsidized while others have to deal more with the balance sheet. I would like to see the numbers comparing those types of schools.

A minor quibble: Land ownership wasn’t actually subsidized in the 1800’s to any significant degree. Instead what you had were areas that were notionally public property but which had not been surveyed, delimited or which contained any public infrastructure. In short, the fact that the government “owned” them was largely just a legal fiction.

In the vast majority of cases, the government grants of land were simply a post facto legalization of the occupation and cultivation of otherwise useless land by settlers. The public had never put any money into the land and therefore the granting of the land didn’t transfer wealth from one citizen to another.

The biggest government subsidy from 1865-1960s came in the form of racial socialism. The government in all places and at all levels granted individuals of certain races the sole right to work in certain jobs. It was considered the responsibility of the state to ensure the economic and social advantage of white people in the face of superior economic competition from blacks, immigrants, asian etc. The very first Jim Crow laws were economic laws designed to prevent highly skilled freedmen such as blacksmiths from competing against whites. In the north, racists unions seized jobs and blocked all non-Whites from competing for the jobs. The trend intensified in the early 20th century with the rise of eugenics movement which combined, pseudoscientific racism with “progressive” idea that the state had a responsibility to protect the genome of the human species itself.

Racial socialism did represent massive transfer of wealth from non-whites to whites. It both arose from and was reinforced by a sense of entitlement. Whites did not believe they had a moral obligation to compete on a level playing field with non-whites.

The health care subsidy is largely a massive economic transfer between generations. It’s great danger is that medical spending will inevitably increase to consume a significant part of our total GNP. Soon, people won’t just want diseases cured but will demand actual subsidized enhancements. When that happens, we will end up in a de facto socialist state.

I’m surprised not to see railroads included as an example of subsidy. The federal government gave them every other section of land along the right of way as a subsidy. I believe the panic of 1873 was the end of a railroad bubble, sort of like the internet bubble of 2000. I wonder of we could think of 1929 as the end of a bubble of automobile and radio stocks. Only the errors of Hoover and Roosevelt turned it into a depression.

The only way to control health care spending is to introduce a market mechanism. In 1960, 47% of health care spending was out-of-pocket. Now it is 12%. The French have done it. I think we may see it as a larger and larger percentage of the medical profession “drops out” or “goes Galt.” I know many physicians who have quit Medicare and even private insurance to practice for cash.

Most of the sections granted to railroads were almost worthless at the time of granting. What good is G-d’s square mile when it is a week’s wagon ride from any of the benefits of society?

Yes, it is a subsidy, in that some value was granted. But most of the value was built, not redistributed.

It seems that since the 1930s, and certainly since the 1950s, all the subsidies are essentially transfers. Before 1900, most were grants of nature’s virgin bounty or creation of non-material rights.

The short, fat part of the chart (post 1950) is all funded by debt. There is no plate, only the promise of a plate tomorrow. We’re past subsidy capacity already. Somewhere in those decades the balance moved from symbiosis to parasitism.

I suppose the Congress could still grant people things in Second Life. Linden dollars are not a constrained resource.

Michael Kennedy,

I’m surprised not to see railroads included as an example of subsidy.

There really is no redistribution in the case of land grants because the land was worthless without railroads and settlers in the first place.

Land has no intrinsic value. It only has value when we can use it to perform some kind of work. If you can’t perform work on the land, then it has no value. In the 1800s, making land valuable meant either farms or mines. However there is a chicken-and-the-egg feedback loop that blocks the use of the land and therefore renders it valueless. First, the farmer has to get out to the land, which takes money. Then he has to buy and transport supplies, which takes money. He has to have a grubstake to keep him alive at least for the first year, which takes money. Then he has to have a way of shipping his crops to market, which takes money. So, not only did the land not have any value, it arguably had negative value because farmers and everyone supporting the farmers would have to invest huge sums to make the land valuable.

It’s little known but the federal government did try on several occasions to auction off vast tracts of the Great Plains. They got zero takers because the land was worthless without railroads and farmers on it. No one was going to pay for land that they couldn’t get any value out of without first investing vast amounts of time and resources.

People think that the land grants were redistribution or a subsidy because our intuition of the transfer of landownership is based on land that already has a use which is then transferred to a different owner which puts it to a different use. When a farmer sells farm land to a house builder, we trade one value generating use for another. People therefore assume that the 18th century land grants were just the transfer of value generating land from the collective to individuals.

It wasn’t. What was really happening was that the government was removing the government imposed restriction on the use of the land. Since the land generated no value, the collective lost nothing.

Actually, the railroad grants were wildly profitable for the federal government. As has been mentioned, the land along the rights-of-way was given to the railroads as an incentive, but it was only every other square mile – the government kept the other half and in general sold it later for much more than it would have been worth without the railroad having been built. It was a lot more like a start-up bringing in venture capital – trade a bunch of otherwise worthless equity for the resources to exploit an opportunity.

I am glad people understand that the land grants were not subsidies; they were a smart investment by government. There was also the matter of land-grant railroads agreeing to transport government freight and personnel at half the market price — that finally had to be ended in, I think, 1944. It is also the case that the model for the railroad land grants were the private land grants to public transportation developers — in this case land investors who had bought large tracts of land and couldn’t sell them for lack of transportation. They gave the grants to the State of New York to support the building of the Erie Canal. It worked, and everybody was happy.

The big subsidies to land and railroad development came in the form of the security provided by the US Cavalry, which built and maintained forts all across the west prior to settlement. It also included the costs and payments made to the Indian tribes that preceded settlement; those costs continued in terms of support of reservations, which in fact continues today. It’s pretty crappy support, but it still costs something.

People like to talk about pioneer self-reliance, but in most cases they couldn’t deal with the Indians in any big way until the cavalry came.