I have stated in an earlier Chicago Boyz column that:

“One of the maddening things about researching General Douglas MacArthur’s fighting style in WW2 was the way he created, used and discarded military institutions, both logistical and intelligence, in the course of his South West Pacific Area (SWPA) operations. Institutions that had little wartime publicity and have no direct organizational descendent to tell their stories in the modern American military.”

Today’s column is the story of one of those “throw away” logistical institutions, one that started as MacArthur’s “Mission X”, what became the small boats and coastal freighter fleet that served MacArthur from 1942 through 1947 as Supreme Commander Allied Powers (SCAP) in post-war Japan.

A Liberty ship and two captured Japanese sampans discharge and load cargo at an unnamed advanced base.

Small Boats and Coastal Freighters

General Douglas MacArthur had three more or less distinct types of coastal shipping pools operating with the World War II (WW2) Southwest Pacific Area (SPWA) theater’s 7th Fleet:

1) Large vessels that were US Army or War Shipping Administration vessels assigned to Army including Dutch East Indies tramp steamers and Vichie French vessels (along with freighters commandeered by MacArthur as floating storage when they arrived with intentions of return). These were the Army Transport Service (ATS) vessels that were, under a 1941 reorganization, integrated into the Water Division of the US Army Transportation Corps. They were manned by American and; Australian merchant seamen in part, but primarily by the US Coast Guard on newer ship after mid-1944.

.2) The small ships and boats section with watercraft of less than 1,000 tons displacement, almost exclusively of local SWPA origin with some built for the U.S. Army in Australia’s small boatyards, that were essential for operating in the coral filled waters of Northern Australia, the Coral Sea, Papua/New Guinea and the scattered islands of the Philippines. They were crewed primarily by a mix of citizens from Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, some as young as 15-years old after February 1943, due to a world wide merchant seaman shortage.

.3) The US Army Engineer Special Brigades (ESB) in LCVP and LCM landing craft. Each US Army Engineer Special Brigade — and MacArthur had three in the Philippines, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Brigades — was equipped to transport and land a division in a “Shore to shore” operation of under 135 miles. (which was the practical maximum overnight range of a LCM combat loaded with a M4 Sherman tank.) These brigades required a force of 7340 men, 540 LCMs and LCVPs, and 104 command and support boats to move that division. You can find an excellent site dedicated to the ESB’s here — http://ebsr.net/ESBhistory.htm

Of the three coastal shipping pools, the second was the only one MacArthur had for the first 18 months after he came to Australia. It was made up primarily of anything the Australians would let “Mission X”, what later became the US Army Small Ship Service (USASS), impress from Australian harbors. Two and three mast sailing ships, tugs, fishing boats and 40 year old coal powered tramp steamers less than 1,000 tons fit to be hulks were the main components of that fleet.

This small boat “fleet” operated in the face of Japanese air superiority without even Destroyers for escort — the USN did not allow any US Navy warships past Milne Bay. If these small watercraft had escorts, they were Australian motor launches, US Navy PT-Boats and US Army ESB landing craft gunboats.

Mission X

The story of how this small boat fleet came to be involves a family friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Sheridan Fahnestock. In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Fahnestock proposed re-suppling MacArthur’s Army by using sailing ships, trawlers, and old freighters- in fact any sort of vessel that could escape the scrutiny of the Japanese forces – and for these vessels to slip into one of the countless harbours and bays in the islands in the Philippines. Fahnestock’s proposal reached the ears of Brigadier General, Arthur H. Wilson. Who was another family friend of the Roosevelts.

Gen. Wilson saw to it that Fahnestock and his associates were flown to Melborne Australia to organize a relief expedition for Bataan. Unfortunately, Fahnestock arrived in Melborne roughly the same time General Douglas MacArthur did. In the aftermath of the 30 March 1942 command split that Chief of Naval Operation Admiral King arranged for the Guadalcanal campaign, which not incidentally stripped MacArthur of US and Australian naval forces, Fahnestock was made a US Army Colonel by MacArthur and ordered to use “Reverse Lend Lease Authority” to impress every tug, ferry, fishing trawler, sailing ketchs and schooners in Australian ports to transport supplies from Australia to Port Morseby and then later from Port Morsbey to Milne Bay.

These small boats were the key distribution mode for the SWPA. They moved supplies at night from advanced bases outside the bombing range of the Japanese Army and Naval Air Forces. Like the PT-Boat, their biggest enemy in 1942-43 was the small twin float Japanese sea planes that flew day and night both low and slow enough to spot them. Then either these sea planes attacked, or worse, orbited and reported by radio to awaiting Japanese fighter patrols.

The small ships moving from Port Morseby to Milne Bay were the only real logistical supply the 32nd infantry Division had at the Battle of Buna, New Guinea. A small ship could deliver 10 tons of supplies over a beach at night while a C-47 could air drop 2.5 tons that may or may not get recovered.

As MacArthur clawed his way up the New Guinea coast, the small ship section, serving under several different logistical commands with several names, (Chapter X of “Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas” By: Joseph Bykofsky; Harold Larson spends a few pages explaining them) provided expendable coastal “Sea Trucks” to keep irreplacable freighters and amphibious shipping out of harms way. Even after the Engineer Special Brigades arrived, they kept up this logistical function.

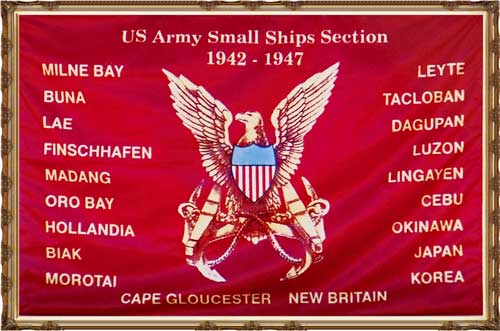

US Army Small Ship Section Campaign Banner

When MacArthur moved into the Philippines, this small ship fleet moved from Hollindia, Biak, Morotai, etc to Leyte to maintain the distribution of supplies to his ground forces from the ports where the larger ships brought supplies. They were still extremely vulnerable to interdiction from _anything_. Especially the suicide motor boats and small numbers of aircraft the Japanese cached at bases all over the Southern Philippines to intredict MacArthur’s sea lines of communications. Dealing with that threat was a large reason for the Southern Philippines Campaign that WW2 US Naval Historian Admiral Samuel Elliott Morison called “unnecessary.”

As the Pacific War was ending, the “US Army Transportation Corps, Water Division, Small Ship Section” was being concentrated in the port of Manila and at Okinawa to support Operation Olympic, the Invasion of Japan. When the Atomic bomb forced Japan to surrender, the USASS moved into Japan and supported American military logistics, as demobilization hit rock bottom, until January 1947. When it was finally and formally shut down.

So now you know the story of another one of those “throw away” MacArthur logistical institutions that didn’t make the naval narrative of the Pacific War.

Notes and Sources —

Army Ships — The Ghost Fleet South West Pacific Area (SWPA), “Forgotten Fleet” by Bill Lunney and Frank Finch, a Review and comment by R. Jackson, http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/rj/swpa/forgotten.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Composition of the Army Fleet in the Southwest Pacific, excerpt from Pages 317-338 of “U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941-1947” by Dr. James R. Masterson, Transportation Unit, Historical Division, Special Staff, U. S. Army October 1949 http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/Masterson.html Last accessed 6-06-2013

The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II, by Captain E. A. Flint, MBE, ED (Retd), and printed in the Journal , “ United Service “ Volume 55 No. 4 Pages 15-20, March 2005 issue, http://www.usarmysmallships.asn.au/html/form_doc.html, Last accessed 6-06-2013

U.S. Army Small Ships Association Incorporated, http://www.usarmysmallships.asn.au/html/fleet.html, Last accessed 6-06-2013

“Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas” By: Joseph Bykofsky; Harold Larson www.history.army.mil/html/books/010/10-21/CMH_Pub_10-21.pdf Last accessed 6-06-2013

Professional Soliders think logistics, not Publicists.

And you GOTTA write a book.

VXXC,

The impression I have of MacArthur as SWPA theater commander was that logistics were his over riding day-to-day concern.

They were even his concern as SCAP, as he replaced the USASS with a Japanese crewed organization that provided the landing craft to the US Navy and USMC for the Inchon landing.

Thanks for another great history lesson. Likely Douglas MacArthur had some irratating personality flaws, but in my opinion he was a genius in strategy and statecraft. It does not surprise me that he improvised in logistics, a most important function. I knew his Chief of Artillery, Major General Hugh Milton, who recounted how his senior staff gathered yearly to celebrate MacArthur’s birthday up until his death and recall memories of that campaign. That kind of loyalty and friendship does not endure without the deepest respect. General Milton was one of the most inspiring and engaging people I ever had the privilege to know. Prior to WW II he was president of New Mexico State and a reserve lieutenant colonel. His opinion of MacArthur meant more to me than any of the opinions of the post war critics who have made their living outside the arena. What he did in and for post war Japan has endured to this day. His comprehensive, forceful approach informs us of the magnitude of what is required to reform medieval, feudal, aggressive societies. There may be other ways that combine containment, gradualism, incentives, counter insurgency, etc., but his five year reconstruction of Japanese institutions has done with the economy of means and duration that demonstrates the genius of this man.

Mike

Dang, make that “irritating”.

And you GOTTA write a book.

I second that notion.

Maybe after I write a couple of years of weekly columns. ;-)

Trent, build it up bit by bit.

This is an important story that has not been told, and a slander has dominated the history for many years.

You, sir, are the man to rectify it.

Agreed on the book!