In previous columns I have been speaking to the US Navy’s communications style and command imperatives to control those communications, especially radio communications and Ultra code breaking intelligence. Today’s ‘History Friday’ column takes that line of research a step further and tells a tale of two strategic bombing campaigns in the winter of 1945 and of secret weather reports in the hands of the US Navy. The two strategic bombing campaigns were the Japanese “Fusen Bakudan” or “Fu-Go” balloon bomb campaign of November 1944 through April 1945 and the American Oct 1944 – August 1945 B-29 bombing of Japan from the Marianas. Both have official narratives. Very few have compared those narratives in relation to how the US Navy exercised distribution control of its Ultra code breaking intelligence from Japanese weather reports.

This column will compare those rival strategic bombing campaign narratives and show how the US Navy’s distribution of decoded Japanese military weather reports on the high altitude jet stream played a role in both, thereby extending the war, and needlessly killing more USAAF B-29 crews, US Navy picket destroyer sailors at Okinawa and Japanese civilians by American B-29 fire bombing.

A METHODOLOGY INTRODUCED AND DEFINED

One of the more interesting things about writing on the end of WW2 in the Pacific is the comparing of institutional narratives with one another. You find a great number of things in those comparisons by remembering the great truth of “Public choice theory,” AKA the use of economics to study the incentives of government. Public choice theory says that institutions are run for the benefit of the people who run them.

This has implications in the way public institutions write their histories. Social science has shown that human beings, teenagers excepted, are far more fearful of the consequences of failure than they are motivated by the rewards of success. That makes failure, and fear of accountability for failure, the strongest motivator for the leaders of large government institutions. In turn, that makes institutional narratives of the past follow a very predictable template. Institutional narratives tend to follow a three step program of hiding failure, talking up the institutional success and the vision of incumbent leaders at the expense of their rivals, and then, finally, telling some truth to the benefit of others in the future. The truth is a very, very distant third compared to the first two parts of this template.

When you lay the official narratives of different events in the same time period in the same place side by side, you find that what is hidden between the narratives is different, what is praised is different, and if you exercise good judgment and validate with original documents, you can find truths to illuminate the hidden areas of rival narratives. If you are very lucky, you will also find a “marker” laid down by the leaders of that time against the narratives, so future events can allow those who care to unlock a deeper hidden truth.**

Such was the case with my research with the Japanese and American strategic bombing campaigns.

PACIFIC COMMAND STRUCTURE BACKGROUND

To understand the two narratives and the ‘marker’ in context requires some background in the Pacific military command structure. First, starting at the top, were the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS). They were the supreme military staff for the western Allies during World War II. The CCS emerged from the meetings of the British-US Arcadia Conference in December 1941. The CCS was constituted from the British Chiefs of Staff Committee and the American Joint Chiefs of Staff. Representatives of allied nations — like Australia, New Zealand and the Dutch East Indies Colonial government in the Pacific Theater– were not members of the CCS. They accepted procedure and were included in consultation with “Military Representatives of Associated Powers” on strategic issues.

The American Joint Chiefs of Staff were formed in early 1942 to face the British Chiefs of Staff with a united front between the American Departments of War (Army and Army Air Force) and the Department of the Navy (Navy and US Marine Corps).

The American members of the Joint Chiefs were General George C. Marshall, the United States Army Chief of Staff, the Chief of Naval Operations, first Admiral Harold R. Stark, who was later replaced early in 1942 by Admiral Ernest J. King; and the Chief (later Commanding General) of the Army Air Forces, Lt. Gen. Henry H. Arnold. President Franklin Roosevelt later added a fourth member as a personal liaison and de facto chairman of the Joint Chiefs in July 1942. That was when Admiral William D. Leahy, formerly FDR’s personal Chief of Staff, joined the JCS.

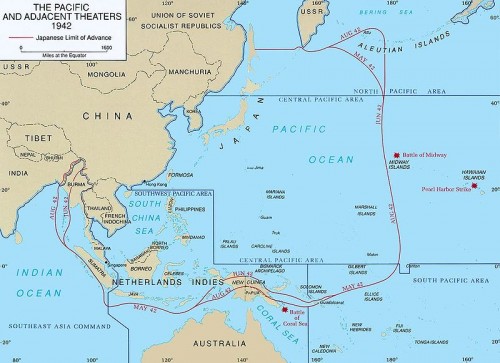

Early in WW2, on 24 March 1942, after the fall of both Singapore and the Dutch East Indies “Java Barrier” to the Japanese, the CCS ceded the entire Pacific to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Six days later the Joint Chiefs of Staff proceeded to divide the Pacific theater into three areas: the Pacific Ocean Areas (POA), the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), and the South Pacific Area. The Pacific Ocean Area command formally became operational on 8 May. The invasion of Alaska during the battle of Midway in August 1942 later saw the POA further divided into the Central Pacific Area and North Pacific Areas.

In terms of theater commands, the SWPA belonged to General Douglas MacArthur and the US Army after the fall of the Philippines. Meanwhile the North, Central and South Pacific theaters all belonged to the US Navy and were subordinate to Admiral Nimitz. Theater commanders controlled their assigned combat units, established logistics priorities to meet JCS objectives in their theater, determined communications policy and the distribution of classified intelligence to all subordinates and attached from other theater units.

MacArthur’s SWPA was a US Army dominated command structure that operated on the principles of coordination and cooperation between services and national forces across vast distances. All of Nimitz’s assigned theaters were Navy dominated ‘joint’ commands with a centralized command and staff structure.

The US Navy, and its Chief of Naval Operations Adm. King most especially, greatly resented the presence of anyone not under naval command in the Pacific. There were many bureaucratic wars between the US Army and specifically with General Douglas MacArthur over the shipping and logistics priorities of the two competing Pacific drives against Japan. However, the bottom line was that it was predominantly the ground forces, air forces and industrial manufacturing capability of Australia that supplied the Pacific theater for the first 18-months of the Pacific War and those belonged to MacArthur’s SWPA Theater. In fact much of the rations Marines and soldiers on Guadalcanal and other Solomon Islands ate in 1942-44 were Australian in origin, provided by US Army Quartermaster units via contracts with Australian suppliers, and paid for by the Australian government via “Reverse Lend Lease.

The Solomons victories in 1942-43, the success of Operation Cartwheel in isolating Rabaul in 1943-44, and the capture of the Marianas Islands in the summer of 1944 resulted in the abolishment of the South Pacific Theater and the folding of it into the Central Pacific Theater as the reborn Pacific Ocean Area (POA) command. Along with this action, the JCS introduced the XXIth Bomber Command of the 20th Air Force into the POA. Under the terms of the JCS directive creating the United States Army Strategic Air Forces (USASTAF) in the Pacific, it was an independent combat command that Admiral Nimitz as theater commander had to supply and could only use for limited operations via prior approval of a direct request to the JCS.

This did not go down well with the Navy.

When USASTAF arrived in the Marianas Islands October 1944, it was bureaucratic war. As it had with the 13th Army Air Force in the Solomons, the 7th Air Force in the Central Pacific and MacArthur’s SWPA, the Navy used logistics and its control of both radio communications and access to Ultra code breaking to play power games with USASTAF and its commanding General Haywood Hansell.

THE RIVAL JAPANESE STRATEGIC BOMBING CAMPAIGN

As this bureaucratic turf war between the American military services was being fought, a different intercontinental strategic bombing campaign was taking shape in Japan. A bombing campaign that had its origins into two events, one well known in America and one that was lost in American military document classification for decades. The first event was the Doolittle Raid launched from American carriers in the spring of 1942. The second event happened in the early 1940s when Japanese weather researchers using high altitude balloons with measuring instruments discovered the eastern transpacific jet stream. The National Geographic article titled “Japan’s Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs” at this link (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/05/130527-map-video-balloon-bomb-wwii-japanese-air-current-jet-stream/) puts it this way:

In the 1940s, the Japanese were mapping out air currents by launching balloons attached with measuring instruments from the western side of Japan and picking them up on the eastern side.

The researchers noticed that a strong air current traveled across the Pacific at about 30,000 feet.

Using that knowledge, in 1944 the Japanese military made what many experts consider the first intercontinental weapon system: explosive devices attached to paper balloons that were buoyed across the ocean by a jet stream.

The Japan-101.com web site picks up and expands the story of the “Fu-Go” balloon bombs as follows (From this link: http://www.japan-101.com/history/fire_balloons_or_balloon_bombs.htm)

…The concept was the brainchild of the Japanese Ninth Army Technical Research Laboratory, under Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, with work performed by Technical Major Teiji Takada and his colleagues. The balloons were intended to make use of a great strong current of winter air that the Japanese had discovered flowing at high altitude and speed over their country, which would someday be known as the jet stream.

The jet stream blew at altitudes above 9.15 kilometers (30,000 feet) and could carry a large balloon across the Pacific in three days, over a distance of more than 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles). Such balloons could carry incendiary and high-explosive bombs to the United States and drop them there to kill people, destroy buildings, and start forest fires. In this way the Japanese would punish the impudence of the Americans for bombing Japan.

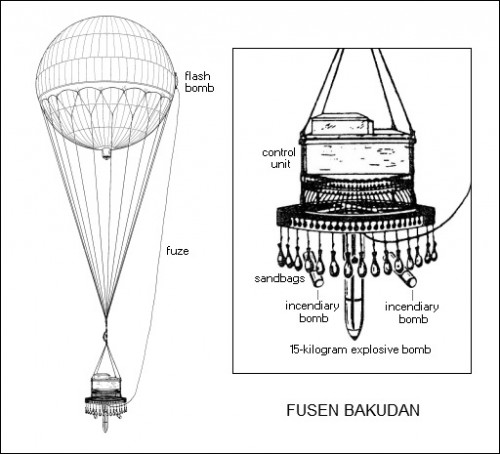

The preparations had consumed much time because the technological problems were acute. A hydrogen balloon expands when warmed by the sunlight, and rises, then contracts when cooled at night, and falls. The engineers devised a control system driven by an altimeter to discard ballast. When the balloon descended below 9 kilometers, it electrically fired a charge to cut loose sandbags. The sandbags were carried on a cast-aluminum four-spoked wheel, and discarded two at a time to keep the wheel balanced.

Similarly, when the balloon rose above about 11.6 kilometers (38,000 feet), the altimeter activated a valve to vent hydrogen. The hydrogen was also vented if the balloon’s pressure reached a critical level.

The control system ran the balloon through three days of flight. At that time, it was likely over the United States, its ballast expended. The final flash of gunpowder released the bombs, also carried on the wheel, and lit a 19.5 meter (64 foot) long fuze that hung from the balloon’s equator. After 84 minutes, the fuze fired a flash bomb that destroyed the balloon.

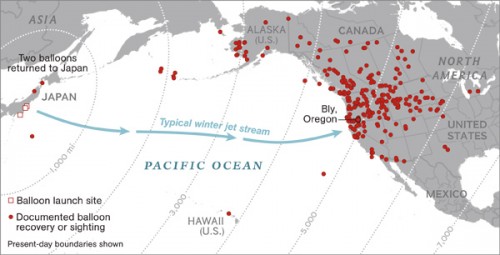

Between November 1944 and April 1945 over 9,000 Fusen Bakudan or “Fu-Go” Balloon bombs were launched at the USA. Various calculations place the estimate of those completing their mission of reaching the USA at 1,000. The US military has documented the impact of less than 300 of these devices including 20 destroyed by fighters.

As the map at the beginning of this column shows, balloon bombs reached Alaska, Canada, Mexico and 16 other U.S. states. They traveled as far east as Michigan and Texas. Most of the balloons were sighted or found in British Columbia, Washington state, Oregon, California, and Montana. Several minor forest fires, in California and Oregon, may have been caused by the balloon bombs.

Japanese military intelligence was using the American press to track results of this strategic bombing campaign. American intelligence through its “ULTRA” code breaking knew that fact. American authorities — through the Chinese intelligence reports and captured Japanese documents — knew of the Japanese biological weapons program and greatly feared that the Japanese would use these balloons to deliver disease to the American heartland.

The American government managed to get the voluntary cooperation of the American press to maintain a complete blackout of the results of the campaign until May 1945. This discouraged the Japanese military, and they ceased launching new balloon bombs in April 1945 after two hydrogen plants supplying balloon bombs had been burned down by B-29 fire bombing raids.

The American censorship policy changed when a group of six picnickers in Oregon died from ignorance by handling a balloon-bomb. At that point, with Ultra telling the American military the balloon bomb campaign had ceased and summer vacation for American schools meaning many more such innocents being exposed to the same danger, the news blackout was lifted and the public informed of the threat.

Improbably, the balloon bombs did score one huge success before the bombing campaign ended, a success well worth the effort made to produce them. According to the US Department of energy document at this link:

http://www.hanford.gov/doe/history/docs/rl-97-1047/c2_s8.pdf

On March 10, 1945, one of the last paper balloons descended in the vicinity of the Manhattan Project’s production facility at the Hanford Site. This balloon caused a short circuit in the power lines supplying electricity for the nuclear reactor cooling pumps, but backup safety devices restored power almost immediately.”

This Hanford nuclear reactor was producing plutonium for the “Fat Man” atomic bomb that would destroy the city of Nagasaki in August 1945…and the Japanese never knew it.

ULTRA, JAPANESE WEATHER REPORTS, AND THE B-29 STRATEGIC BOMBING CAMPAIGN

Despite the decades-long Pacific War B-29 bombing campaign narrative that “no one knew” about the jet stream over Japan, the Japanese offensive balloon bombing campaign makes clear that the Japanese knew. In fact Japanese awareness of, and weather reports for, the jet stream were used to provide for the defense of Japan against B-29 raids. This has been reported in both open and classified sources since the late 1940s. In fact, in 1949 the US Army Seacoast Artillery Research Board survey of Japanese air defenses reported the following in the May-June 1949 issue of the US Army’s Coast Artillery Journal —

In establishing the gun defense, consideration was given to the prevailing wind and the expected direction of attack. The winds were consistently from the west and average 150 to 200 miles per hour at 25,000 to 30,000 feet altitude. The defenses were established on the assumption that we could not bomb effectively from other than within narrow sectors either upwind or down wind.

The Japanese military author of the US Army’s classified Japanese Monograph No. 157 history published in 1952 also stated the following regards the jet stream and Japanese fighter versus B-29 tactics —

Changes in B-29 Tactics

Apparently becoming aware that rigid adherence to the same types of formations and the same approach paths was resulting in losses, the enemy began adopting deceptive and diversionary tactics. The B-29 echelons chose different routes and often separated to attack several targets. In addition, they made changes in their approach routes and often caused interceptor planes to fly into the wind. This was a definite disadvantage to the smaller and lighter fighter aircraft.

American Ultra decoders had by October 1944 broken the Japanese Purple diplomatic, Mainline Japanese Army, Japanese Army Water Transport, Japanese JN-25 Naval and Japanese weather codes. Anyone with Ultra access should have known about the jet stream over Japan. It raises the question: Why didn’t General Hansell know about the jet stream? The answer comes from a ‘marker’ via General Hansell himself, from pages 203 – 204 in his 1986 book “The Strategic Air War Against Germany and Japan: A Memoir” ** –

…Our weather information came chiefly from a nightly B-29 flight to Japan. I had a meteorological officer who did a magnificent job under almost impossible conditions. His name was Col. James Seaver; I had known him in England. He knew perfectly well that my decision to “go” or to “stand down” depended directly upon his forecast. He also knew that his estimate was going to be better than mine, so he stated it without equivocation. He said what he thought would be the case, without hedging it with subjunctive clauses. Sometimes he was wrong, but more often he was right. I relied upon him heavily and was careful never to criticize when the weather forecast did not pan out.

The XXI Bomber Command had no special liaison unit (SLU) to receive Ultra information — a grievous omission. I cannot understand why. Group Captain Winterbotham in Ultra Secret drops the casual statement:

In Brisbane (Australia) many of our main signals now came from Delhi, but radio blackouts were frequent. Sometimes signals came via the Australia Post Office cable, or even radio from Bletchley (England), and Japanese weather reports came up from Melbourne by teleprinter, so the SLU at Brisbane had a bit of a job sorting out what was going on.

What Colonel Seaver would have given for those Japanese weather reports! Weather over Japan was our most implacable and inscrutable enemy. Such reports received through Ultra were of great value in the strategic air war against Germany; they would have been priceless in the air war against Japan. It seems simply incredible that no one “in the know” recognized our need, especially for Japanese weather reports, and took steps to supply me and later General LeMay with an SLU.

The person “in the know” that Hansell was referring to was Admiral Nimitz. Only Nimitz as the POA Theater commander could authorize an Ultra special liaison unit (SLU) to the XXIth Bomber command. Not even the 2nd in command for the 20th Air Force, General Harmon — a former commander of the 13th Army Air Force in the Pacific who had gotten Ultra intelligence from General MacArthur, and had later succeeded Admiral Halsey as a South Pacific Theater commander under Nimitz — someone who was very much “in the know” for Ultra, could countermand Nimitz on providing an Ultra SLU for Hansell.

General Harmon’s death flying to Washington DC to “clear up Army Air Force chain of command issues in the Pacific” takes on entirely different shades of meaning in light of General Hansell’s Ultra weather report ‘marker.’

CONSEQUENCES

General Hansell’s XXIth Bomber Command spent October 1944 through January 1945 learning how to bomb through the jet stream accurately. It turns out that it is possible and that there was a “Book Solution.” As the 1949 the US Army Seacoast Artillery Research Board Survey states, bombing accurately across the jet stream was impossible. The XXIth Bomber Command learned by bombing with the Jet stream that it was impossible, as the ground speed of 500(+) miles an hour (800kph) was far too fast for the analog computer Norden bomb sight.

Bombing into the jet stream at a slightly lower altitude of 27,000 feet was a different story. The ground speeds fell from 300 miles an hour to between 100 and 150 MPH (160 to 240 KPH), which was within the Norden bomb sight’s capability. The fact that the bombs trailed further behind the aircraft when dropped could be compensated for by adjustments in bomb trail built into the sight to account for the drag of different bomb types.

Against German flak gun air defense this would be suicide. Against the Japanese, it wasn’t. It was not until Hansell’s last B-29 mission on 19 Jan 1945 against the Kawasaki aircraft plant located near Akashi, after long experience of learning by dying against Japanese fighters and poor high altitude Japanese anti-aircraft gunnery, that Hansell’s staff hit on that solution. It was, by then, too late for Hansell. He had been relieved by General Curtis LeMay.

Had Hansell and his staff been aware of Japanese upper altitude jet stream weather from the beginning, these adjustments would have happened sooner.

For want of weather reports, the XXIth Bomber Command would have done far more damage to the Japanese aircraft industry, and suffered fewer B-29 crew deaths from repeatedly and ineffectively striking the same aircraft plants over and over again.

For want of experienced B-29 crews by the XXIth, who would have lived and struck effectively using the better tactics weather reports could have provided, the reduced output of Japanese aircraft from approximately late November 1944 through the start of LeMay’s firebombing campaign in March 1945 didn’t happen.

For want of destroyed Japanese aircraft plants these weather reports would have made possible, there were suicide aircraft reserves for the Okinawa campaign. Thus were destroyed many US Navy picket destroyers that should have lived, as the Japanese need to maintain a reserve of suicide aircraft for the Ketsu-Go final defense against invasion that would have truncated the Kamikaze campaigns which those destroyers suffered in May and June 1945.

For want of a more successful with precision bombing campaign those weather reports would have provided, the fire bombings of Japan General Hansell resisted doing would have been delayed further still before the A-bomb arrived, thus reducing the final death toll of Japanese civilians in the Pacific War.

And finally, for want of a Pacific War “narrative comparison” column, you didn’t know any of the above…until now.

**A recent example of this “Laying down a marker against future events” leadership behavior can be seen in the NSA’s “Snowden scandal.” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) made repeated warning about the NSA and American privacy. He went so far as to ask Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper Jr. in public session whether the NSA was collecting phone data on millions of Americans. Clapper denied that the NSA did that. Snowden showed that with the NSA’s metadata programs, Clapper was not telling the truth. Thus collapsed the post 9/11 NSA’s lack of public accountability for the secret surveillance state it created.

Notes and Sources

1. A Brief History of Japan’s Less-than-Effective Balloons of Death

http://jonathanbellinger.typepad.com/blog/world-war-ii/

http://www.hanford.gov/doe/history/docs/rl-97-1047/c2_s8.pdf

2. Combined Chiefs of StafF

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combined_Chiefs_of_Staff

3. E. Bartllett Kerr, “Flames Over Tokyo – The U.S. Army Air Forces’ Incendiary Campaign Against Japan 1944-1945,” Donald J. Fine. Inc, N.Y. C 1991, ISBN 1-55611-301-3 pages 101 – 121

4. Fire Balloons – Incendiary Devices Launched by Japan During World War II

http://www.japan-101.com/history/fire_balloons_or_balloon_bombs.htm

5. Haywood S. Hansell, Jr. Major General, USAF, Retired “The Strategic Air War Against Germany and Japan: A Memoir,” Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C., 1986, ISBN 0-912799-39-0, pages 203 – 204

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/Hansell/index.html#contents

6. Japanese Fugo Bombing Balloons

http://www.stelzriede.com/ms/html/mshwfugo.htm

7. Japanese Monograph No. 157, HOMELAND AIR DEFENSE OPERATIONS RECORD, PREPARED BY HEADQUARTERS, USAFFE AND EIGHTH U.S. ARMY (REAR) 9 June 1952, pages 116

8. Japan’s Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs – The Japanese harnessed air currents to create the first intercontinental weapons—balloons

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/05/130527-map-video-balloon-bomb-wwii-japanese-air-current-jet-stream/

9. Brigadier General Rupert E. Starr, President, Seacoast Artillery Research Board, “Survey of Japanese AAA,” COAST ARTILLERY JOURNAL, MAY-JUNE 1949, pages 23 – 29

Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy states that in any bureaucratic organization there will be two kinds of people”:

First, there will be those who are devoted to the goals of the organization. Examples are dedicated classroom teachers in an educational bureaucracy, many of the engineers and launch technicians and scientists at NASA, even some agricultural scientists and advisors in the former Soviet Union collective farming administration.

Secondly, there will be those dedicated to the organization itself. Examples are many of the administrators in the education system, many professors of education, many teachers union officials, much of the NASA headquarters staff, etc.

The Iron Law states that in every case the second group will gain and keep control of the organization. It will write the rules, and control promotions within the organization.

From http://www.jerrypournelle.com/reports/jerryp/iron.html

It’s like the story of a new MP in the House of Commons. He takes his seat, looks across the floor of the house, and remarks to the bloke next to him “It’s nice to see the faces of the enemy”. The bloke corrects him. “No: those are your opponents. Your enemies are behind you.”

This is OT but Obama appears to have succeeded in politicizing he Medal of Honor even more than Clinton did. Anti-war Democrats seem to think medals should be awarded by quota. There may even be some deserving cases in there but who will believe that now ?

Sorry for the diversion.

This is amazing, Trent. It completely rewrites a key narrative in the history of the war. The story has been that the B-29 program, at immense expense, was a complete waste and failure due to the jet stream, and only LeMay’s brutal extemporization of a low level fire bombing campaign salvaged anything from what would have been a humiliation for the Army Air Corps and for the USA. Now we see that accurate bombing was actually possible, especially in light of weak Japanese air defenses. It also shows Hansell in a very different light. He is usually presented as a hapless leader who refused to face the impossibility of using his bombers as planned and pointlessly persisted in trying to do precision bombing when it was a physical impossibility, and only the tough and realistic LeMay was willing to simply switch to slaughtering civilians as a way to get at their war production. Why didn’t Hansell make a better case to his superiors that they were figuring out to bomb despite the jet stream? Why wasn’t LeMay open to that if so?

Lex,

LeMay’s success rested on a logistical foundation that Hansell built. The bureaucratic games that were played to get and keep that foundation are the subject of the next column.

Make no mistake about Hansell being a precision bombing true believer. He did not _hear_ what General Lauris Norstad was telling him about incendiaries. Most especially implications of the fact that Norstad was the patron of the M-69 incendiary bomb development program.

But above all, Hansell and then LeMay were handicapped by the Navy.

ADmiral Nimitz has always been portrayed as that grandfatherly genius who was very accomodating to his opposites in the Army, though I do remember reading he kept a photo of MacArthur to remind himself not to make “Jovian Pronouncements”. It was always made to look like it was King who played full time hardball. But what I’m beginning to see here is that Nimitz was complicit in keeping a choke hold on information.

Since Halsey seemed to have a genuine friendship with MacArthur, I wonder if he was also kept in the dark my King and Nimitz when they chose to.

Lauris Norstad

What a great name.

My future dad, a B-29 instructor pilot, missed Japan by weeks. His wing was about to fly to the Pacific. He was swimming laps in an Army Air Force base pool in Arizona when his copilot interrupted with a question. “What does it mean that we’ve dropped an atomic bomb on Japan?” My dad replied, “You and I won’t go to war. We won’t have to kill women and children to end the war.” The copilot asked my dad the question because he knew my dad’s college study was physics.

Several times in conversation over the years my dad told me about the B-29 encounter with the jetstream headwind. He told me that higher ranks wanted to court martial pilots that turned back from Japan, claiming fuel gauges said the round trip would not happen. The higher ranks believed the pilots lied, that they had reduced throttle and slowed down to be late to checkpoints and had dumped fuel. Eventually the evidence persuaded folks that the jetstream existed.

That others on the U.S. side of the war knew about but did not share with the AAF the jetstream’s existence meant, as Trent suggested, complicity in the deaths of both U.S. flyers and Japanese civilians. That the others included those in another military arm who were not just plain dummies so that they could not understand the implications makes that complicity even bolder.

A great history on the B29s was in the book Flyboys by James Bradley (author of Flags of Our Fathers).

He was saying that the B29 was designed for high altitude bombing at a time when they knew nothing of the jetstream.

It was this knowledge that forced them to low level bombing – sometimes 1000 feet.

With the terrible firebombings an image that stays in my mind was the site of these huge new planes – with the fire reflecting off their shiny fuselage…visible from the ground.

In regards to the Medal of Honor deal, the reviews were kicked off in 2002 by Congressional order (it’s their medal, after all). So about the only thing President Obama has to do with it is to actually present them to whomever.

As long as they are using the information that’s on file (which should have been written soon after the event), I don’t have much of an issue with it. You could argue that such a review would be valid for *all* recipients of the 2nd highest honor, since people screw up awards for all sorts of reasons.

Roy,

The first two minutes of the US Navy training film I linked to on Youtube, under the first map in the article, shows how well informed the Navy was by Ultra decoded Japanese weather reports.

I am still tracking back through NARA to see its wartime issue date.

As for the USAAF Bomber General arrogance in the face of the raw data from pilots on the jet stream winds…they had their reasons.

As a rule USAAF Bomber generals were young, arrogant, very technically competent in a very narrow sense of how to get bombers with the maximum payload over a target, and generally ignorant outside that narrow technical background. They were also personally brave and lead by flying the lead bomber formations. Their primary means of feedback was personal combat experience. That last fact had a lot of implications for what happened over both Germany and Japan.

The German flak in Europe was so bad that roughly 30% of every heavy bombardment aircraft that flew over a heavily defended locality suffered battle damage. That was why the 8th and 15th Army Air Forces had such horrible serviceability rates (in the high 50% range) compared to the 80-90% for B-29’s at the end of the Strategic Air Campaign versus Japan.

It didn’t matter the size of the raid in Europe or what tactical disposition was used. All the improved tactical dispositions did was reduce the severity of the total force battle damage by reducing exposure times.

Don’t get me wrong, that was important in that fewer bombers took the sorts of engine or flight control surface damage that prevented them from flying close formation with other bombers.

The absolute worse place to be as a damaged straggler heavy bomber was to be in the neighborhood of the bomber stream, as that was where German fighter were. The second worse place was to be a straggler away from the bomber stream heading back to base, because that is where German radar directed fighter patrols were.

If a damaged bomber headed for Sweden or Switzerland, the crew was going to live because the German fighters didn’t waste their time on bombers heading for internment. Word of this fact got around to bomber crews after the two Schweinfurt raids and internments sky rocketed.

It wasn’t until after the war, when shot down bomber crews were debriefed and the interned planes were really looked at by USAAF repair crews, that the Bomber generals learned how effective German flak defenses were and found of from freed POW crew debriefings that most German fighter kills were of flak-damaged planes. Which meant by extension that most of the interned plane crews would have died had they tried to make it to England.

IOW, German fighters were so deadly because German Flak was.

Japanese Flak wasn’t nearly so deadly, so neither were the Japanese fighters. The Japanese fighters had far fewer damaged bombers to pick off than the German fighters did.

None of that information was available to Hansell, LeMay or their subordinates in the Strategic Bomber Campaign versus Japan, and both Hansell and LeMay were forbidden to fly B-29’s over Japan.

Now that I think of it FDR was a Navy man too..

“As long as they are using the information that’s on file (which should have been written soon after the event), I don’t have much of an issue with it. You could argue that such a review would be valid for *all* recipients of the 2nd highest honor, since people screw up awards for all sorts of reasons.”

This has been long said about the DSC. My point is that the recipients are chosen for political reasons. Look at the criteria. Clinton awarded some medals that had been passed over for various bureaucratic reasons. One was Ben Soloman but the Obama medals are all awarded for racism reasons.

Some may be valid but I am suspicious of this bunch.

Editorial Note — I added a Pacific theater map to the column to illustrate the text..

If anyone thinks the award of heroism medals are not highly influenced by upper level command subjective factors, they are mistaken. The higher the level of award, the more subjective factors count. Given the highly politicized flag officer corps we have, you can bet they understand how to use this opportunity to “do the right thing” IAW the POTUS’ and his hacks’ objectives. There are never a shortage of heroes, it is all about how it is written up and who is championing the recommendation.

Historically, the CMOH has been predominantly awarded to those who performed highly heroic actions under heavy combat where others were spared at the cost of horrific injury (often multiple injuries) or death of the honoree in circumstances where others did not act. The difference between the award of the CMOH and a DSC or even Silver Star has often been inexplicable based on the objective facts establishing merit. Other factors have historically often been more decisive. In the past it has been common for CMOH awardees to express feelings that their actions were not unusual, heroic or deserving of such exalted recognition. I’ve known several of these heroes and I can attest that this is their honest feelings, not some false modesty. The reason seems to be that they know personally of others equally deserving who were not so recognized and that their actions were spontaneous with little thought to the danger. When I recently saw one of the awardees express relief that he was recognized and was obviously very pleased with himself during the ceremony, I almost puked. That has never been the norm.

In this age of “social justice” and highly politicized military command structure, such an opportunity as this “review” will not be wasted. Wonder what the POTUS will say at the ceremonies. Maybe they will just arrange a group ceremony with the families sitting at the rear of the audience of members of congress and senior military and DOD appointees providing the back drop for a smiling Barry passing out the goodies.

Mike