[cross-posted on Albion’s Seedlings]

Instapundit has a post up on a book about the Medici and Italian banking:

SO I’VE BEEN READING TIM PARKS’ Medici Money: Banking, Metaphysics, and Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence

. It’s a pretty interesting book, with a juxtaposition of prejudices against sodomy and usury (both seen as “against nature”) as a background for the Renaissance.

It’s mostly a history of the Medici banking empire, though, and it’s interesting to see how the bank declined. The problem was the passing of a generation of bankers who loved the work — Cosimo Medici said that he’d remain a banker even if he could make money by waving a wand — and its replacement by those who weren’t terribly interested in the actual work, but rather in the opportunity their jobs provided to hang around with kings, queens, and cardinals. Not surprisingly, things went downhill fast once that happened.

I think that’s a metaphor for politics and journalism today — and a cautionary example for the blogosphere.

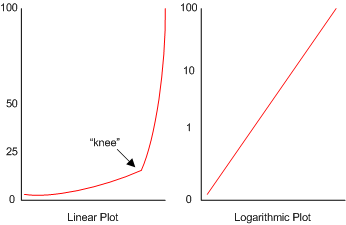

Economic historian Joel Mokyr believes that these periods of innovation in technology (hard and soft) can be spotted repeatedly back to the Greeks (see his Gifts of Athena: Origins of the Knowledge Economy reviewed here, and the The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress

). The distinction, finally, with the Scientific/Industrial Revolution was that the inevitable rent-seekers couldn’t get an adequate grip and the Malthusian caps were breached. The widening of the “epistemic base” (which Mokyr represents with the symbol omega) was creating usable knowledge (symbol lambda) faster than it could be controlled or stamped out by antagonistic parties. To quote Mokyr: “The broader the epistemic base, the more likely it is that technological progress can be sustained for extended periods before it starts to run into diminishing returns.” A virtuous cycle rather than a negative feedback loop gets established. He’s got a great article on Why was the Industrial Revolution A European Phenomena? available in .PDF format.