[ cross-posted from Brainstormers on the Web ]

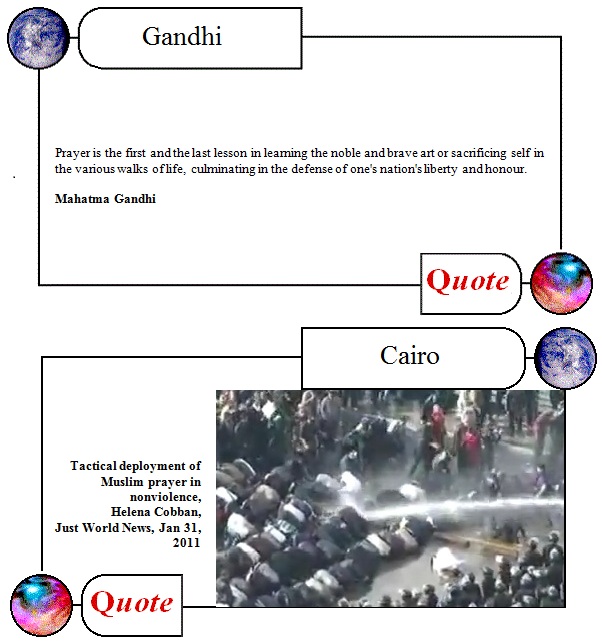

For location / background, see Helena Cobban, Tactical deployment of Muslim prayer in nonviolence.

The image is from the middle of this YouTube video — you can see the prayers begin around the 3.25 mark, and the ending is also worth watching, as Cobban notes.

Ghandi advised the English to surrender to Hitler and said that, even as they were enslaved, they would know they were morally superior to Hitler. Ghandi was fortunate to never encounter Hitler.

Ghandi changed his mind about that later in the war, He had been naive about the danger that the Nazis presented. Like many people in the first year or two of the war, he saw it as just a repeat of WWI which was viewed as being a conflict between moral equals e.g France was no more moral in its war aims than Germany was.

Later, after the war, he made it clear that non-violent resistance only works against someone who is intrinsically moral in the first place e.g. the British in India. Many in Britain thought the Empire good for both people’s and wanted to preserve it but even the most ardent imperialist weren’t willing to slaughter millions of Indians just to preserve India as a colony. Ghandi eventually recognized that and conceded that non-violence had its limits and that at some point you had to fight.

Unfortunately, Ghandi’s more pragmatic stance has been swept under the rug and replaced with a stereotype of “Ghandi said that non-violence is always the answer in every circumstance.”

In any case, the protestors in Cairo are counting that the riot police will not simply kill them outright because of the mutually shared values of respecting religion. In that regard, they are following Ghandi’s real playbook.

It’s Gandhi, guys, not Ghandi — and the Mahdi, not the Madhi, which is the “opposite” typo that I sometimes commit. Anyway…

*

A few points.

Gandhi really seems to have been a fascinating mass of contradictions and tensions. A friend of mine and one-time winner of the National Defense University’s Sun Tzu Award thinks we can understand him best as a master strategist, while from my own religious studies perspective his attempt at the brahmacharya lifestyle is of considerable interest — and it may well be that his doctrine of ahimsa, divorced from the biography of the man himself, is a little easier to puzzle out.

There’s an account of Gandhi’s two letters to Hitler on the site of Koenraad Elst — who interests me anyway because of his writings about Ayodhya and the Babri Masjid / Ram Janmabhoomi controversy from a Vedic perspective.

Shannon writes, “he made it clear that non-violent resistance only works against someone who is intrinsically moral in the first place e.g. the British in India.” Is that Gandhi, or is that later commentary? I’d be interested to see a quote…

In any case, Shannon’s point about the “stereotype” of Gandhi is eloquently made by Gandhi himself in his words:

and:

*

Thanks for the continuing conversation — regards to all.

Ghandi, or Gandhi, was not such an exemplary character as depicted sometimes. He convinced his wife not to have western medical treatment when she was ill and she died. He, on the other hand, had his appendix out promptly when he developed appendicitis.

Agreed, Michael:

Isn’t that always the case? There’s the pedestal, and there’s the man, there’s the hagiography, and there’s the life? I mean, with those who are perceived by some group to embody their ideal…

From another standpoint, there are those we can admire, and those we would elect — not by any means always the same people. It took me quite a while to make that distinction.