Lewis, William, The Power of Productivity: Wealth, Poverty, and the Threat to Global Stability, U of Chicago Press, 2004. 339 pp.

[cross-posted on Albion’s Seedlings]

Preliminary headlines on the upcoming riot season in Paris are starting to appear, recalling the difficulties that European countries face in boosting their economic performance: reducing unemployment and increasing economic growth. Fareed Zakaria’s article in the Washington Post earlier in 2006 entitled the Decline and Fall of Europe is a quick and readable summary.

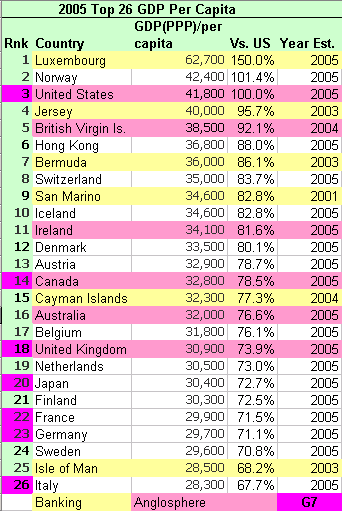

Zakaria quotes a particularly interesting OECD report called “Going for Growth” that shows Europe, rather than catching up to America in per capita GDP, has in fact been falling behind over the last 15 years. Efforts to catch up, while noteworthy and politically difficult, have essentially failed. When the GDP figures are adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP), from country to country and around the world, we end up with shocking tables like the following:

Source: CIA World Factbook

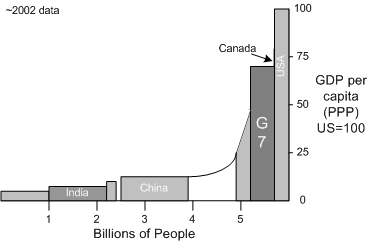

and this:

Source: Adapted from Lewis, The Power of Productivity, 2004.

The United States doesn’t simply lead the world in GDP per capita (PPP adjusted). It is in a class (fully acknowledging its size) entirely by itself. Adding 1 million net citizens every nine months (one every 13 seconds), America is extending its lead in prosperity over not only poor and moderately wealthy nations, but over virtually all of its erstwhile companions on the “heights” of Mount Prosperity. Next-door neighbour Canada is the only eight digit population close to the US, coming in at 78% of US per capita GDP (PPP adjusted).

Most disconcertingly for those of us interested in history, the distribution of per capita wealth across the globe in the last century has barely budged. The only sizeable nation to make the jump from poor to rich in that period was Japan. Grimmer yet, after a half-century of international efforts at economic development, less than 5% of the world’s population has made it into the “middle-income” nations – ranked between 25 and 70% of US per capita GDP. That means we cannot expect any “new” wealthy nations (on a per capita basis) within most of our lifetimes.

Despite China’s massive growth in GDP, its per capita GDP remains very modest. As a recent commentator noted, China will get old long before it gets rich. And at current rates, both it and India would take centuries of per capita GDP growth to reach the levels currently held by the 300 million Americans living today.

The OECD responded to this disturbing pattern with a common European solution: redefine the problem out of existence. As described in a generally laudatory article in the Economist, the OECD decided that social values such as the desire for leisure, and the desire for greater income equality within a nation should permit the adjustment of the rankings of relative prosperity between nations. Well, money isn’t everything, we might grant, while still clinging to the idea that 82 million Germans earning 71 cents for every dollar 300 million Americans earn might just be a long term problem. Who pays for the old-age homes in 2025, for example?

Fifteen years ago, the folks at McKinsey Global Institute under the direction of William W. Lewis began studying globalization from a more anthropological perspective. This led them to focus on relative national productivity (the ratio of the value of goods and services provided consumers to the amount of time worked and capital used to produce the goods and services) at a microeconomic level. More specifically, they began examining countries, industry sector by industry sector, to identify the patterns of productivity within national economies.

To their surprise, their national productivity information tracked GDP per capita information (adjusted for purchasing power parity) very, very closely. Those nations that were most productive on average were also those that generated the most per capita wealth. To quote a summary of their work:

Fifty years of focus on the macroeconomic policies of developing nations didn’t lift their income levels substantially: 80 percent of the world’s people still get by on less than a quarter of the average income in rich countries, much as they did a half century ago. The McKinsey Global Institute’s research in 13 countries suggests that the productivity of the large industries where most people work — “old economy” sectors like retailing, wholesaling, and construction — has the most influence on a country’s gross domestic product. To improve the economic welfare of individuals, countries must increase their productivity, primarily by encouraging economic competition.

Their conclusion:

Global economic agencies underestimate the significance of a level playing field. Competition is more important than education or greater access to capital markets in lifting a country’s gross domestic product. To reduce barriers to competition, policy makers must stand up to business special interests and focus more on the welfare of consumers.

In The Power of Productivity: Wealth, Poverty, and the Threat to Global Stability, William Lewis takes the results of over a decade of research, and the country case studies, and assembles a compelling and very readable review of what productivity is, where it resides (within different countries) and how difficult it is to achieve in all but a handful of nations. He looks at both “best practice” and “bad practice.”

In the course of doing this research, he claims to have constantly tried to avoid using the United States as a benchmark but both his clients, and the productivity statistics, demanded otherwise. Apart from the steel, automotive and electronic industries in Japan, and retail banking in the Netherlands, virtually no other nation on earth has more productive agricultural, industrial, and service sectors than America. It is in the breadth of its economic productivity that the United States finds its great advantage over the rest of the world.

For Lewis, the absolute central issue is the competitiveness of product markets — responding directly to consumer need. The flexibility of labour and capital markets are important, but to him, they are secondary.

Nominal US competitors such as the EU leading industrial nations have some narrow productive manufacturing sectors but much of the rest of their economies (agriculture, housing, services) is quite unproductive. EU total GDP may well approach US levels but the EU now includes 170 million more people than the US. Per capita GDP, especially adjusted for PPP, still places the leading EU countries at little more than 70% of the US. The United Kingdom is a tiny bit more successful than its continental brethren, and Canada a touch still more productive. But the gap with the US is still astonishing, and still growing.

Japan leads the world in the productivity of several sectors of its economy. Its techniques (such as the Toyota Production System) are adopted with great success by American plants, so we know that great productivity is not culture-specific in some ethereal way. But much of the rest of the Japanese economy reaches productivity levels barely 40% of the US in areas such as food processing, housing construction, retailing and wholesaling. When averaged across the economy, Japan fairs little better than Europe in average productivity and GDP stats. And its growth in productivity, like the Europeans, seems stalled in comparison to America since the early 90s. The tremendous post-WW2 global injection of capital and labour, which offers medium-term increases in productivity as an economy industrializes, has come to an end. The Japanese public is still willing to put up with dismal returns on its savings in order to subsidize the inefficiencies of the Japanese economy. For how long is anyone’s guess. Vast portions of the populace in the Japanese economy are working at very low levels of productivity. Housing, for example, operates less productively than the United States did in the 1930s.

Korea, a dweller on the “foothills” of the GDP wealth curve, is trying to follow Japan’s approach to productivity growth but it shares the same narrowness of high-productivity sectors across its economy. And it shares its same vulnerability to stagnation and economic crisis when the ability to improve productivity by working longer or adding cash reaches a limit. A protectionist economic system ensures that only a select few sectors of the economy actually face international competition and exposure to methods of improved productivity.

When Lewis turns to Brazil or Russia or India, virtually no portions of their economies reach 50% of the level of productivity of the United States, unless they are small industrial enterprises run according to Japanese or Western management principles as fully-controlled branch operations. For much of the agricultural sector, per capita productivity in these nations can run as low as the single digits, in some cases, merely one or two percent as productive as the United States. In light of the fact that 65 million Indians are in the dairy farming industry alone (the largest group of people in the world in one business), it’s little wonder that Indian per capita GDP will remain very low for a very long time. The much vaunted Indian IT industry, operating at 50% of the productivity of the United States, yet represents 0.1% of the Indian workforce. Islands of productivity as small as this can’t make a dent in the average stats of a nation where 60% of the workforce is still in agriculture.

Lewis admits that his research surprised him a number of times over the decade or so that information was assembled. In the early part of the 20th century, when the United States had a per capita GDP somewhat similar to the middle-income nations of the modern world, the portion of GDP represented by the American government was about 8%. Today, for countries such as Brazil and Russia, struggling their way toward increased productivity, their government GDP percentage is closer to 40%. Thus the relative amounts of per capita capital available for private commercial economic expansion in these countries are a fraction of what was available to the American economy before the First World War!

So what about that American economy? Apart from a few industries where Japan and the Netherlands have something substantial to teach it, why does America keeping growing wealthier than everyone else? Was it the computer boom of the 90s?

According to Lewis, no. The industries (large enough to make a real dent in the productivity stats, remember) that made the greatest gains in the 80s, 90s and 00s weren’t high-tech. They were the massive retail and wholesale businesses who employ millions and sell to tens of millions more. Those businesses, typified by Wal-Mart, were able to rationalize, consolidate and optimize in ways unmatched by the companies of any other nation in the world. The disruption to local businesses, mid-sized wholesalers and retailers is well-known. Sears and K-Mart and a huge number of small paper-pushing wholesalers entered very troubled water and many did not survive. In their place, new giants appeared — much as standardization and automation had struck the agriculture, manufacturing, and housing businesses in America decades before. More importantly, Wal-Mart’s methods were matched by a new generation of retail stores — the Targets, Office Depots, etc. that applied the new information technology to improve their businesses. Silicon Valley itself may only have had a modest impact on the productivity stats of America but the spinoff benefits of its products, especially once AMD began to compete with Intel, were applied to vast sectors of the economy with tremendous success.

In a brief review for a focused blog, it’s impossible to do justice to the broader microeconomic argument which Lewis provides across hundreds of pages. One could do worse however than read the interview with Lewis in TCS Daily which was so striking that I purchased his book for further study. There is also additional information at the McKinsey website on the title.

I can summarize his arguments briefly and then turn to some implications for the Anglosphere:

1. Poor national economic performance can be better understood by analysis at the level of individual industries rather than macroeconomics alone.

2. Differences in capital and labour markets are overstated as determinants of national economic performance. Differences in competition in product markets are much more important.

3. While attention to exchange rates, inflation and government solvency were emphasized to developing nations, the importance of a level playing field for competition in a country was vastly underestimated.

4. The importance of the education of a workforce has been taken way too far. Education is not the way out of the poverty trap. Workers around the world are successfully trained on the job for high productivity. In a favourite Lewis anecdote, illiterate Spanish-speaking unskilled labourers in Houston have some of the highest construction productivity levels in the world because of the system they work in and how they are trained.

5. The solution for developing countries does not start with more capital — it starts with the way that it organizes and deploys the capital and labour it has. Balanced budgets and better productivity would allow most countries to access all the capital they need from both domestic and foreign sources.

6. “Social objectives” which distort markets severely and limit productivity growth also slow economic growth and cause unemployment. Creating a level playing field and then managing distribution of a bigger pie through taxes on individuals is the better sequence.

7. Big governments demand big taxation. The more informal the economy, the more legitimate and productive businesses are held back by such taxation. Western countries did not have this problem in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

8. Salvation does not come from elites. Elites are responsible for big government and reward themselves richly. They are in the business of the un-level playing field.

9. Protectionism of national industries keeps highly productive companies out of a country. Poor countries have the ability to grow much faster than people think but subsidizing low productivity is self-defeating.

10. Production unlinked to consumer desire misunderstands the real nature of “value.” Production is only worth what people will pay. Only one force can stand up to producer special interests — consumer interests. Most poor countries are a long way from a consumption mindset and consumer rights. As a result, they are poor.

Again, I encourage anyone interested in the global economy, and in evaluating how nations differ in their economic attitudes and success, to read this book. It’s very well written, lucidly argued, and offers up some very useful information (and fascinating anecdotes) on the national economies discussed above. The chapter on India, particularly, is a sobering balance for those considering India’s role in the “Third Anglosphere.”

Anglosphere Implications

The Power of Productivity offers us yet another way of examining economies, both modern and historical. On the one hand, the Anglosphere economies enjoy a position of affluence on the global ranking of per capita GDP, yet that troubling 20-25% gap in productivity between the United States and virtually everyone else needs explaining and examination.

For myself, I think Lewis’ book is yet another strong argument for suggesting that America is a unique data point, even within the Anglosphere. To have reached such a size, and such an economic and demographic growth rate over the last hundred years is unprecedented. More importantly, since 1990, there is every indication that other industrialized nations have stalled in keeping up. Other Anglosphere nations suffer perhaps a little less than Japan or continental Europe but still — there is something about Lewis? point on consumer focus, and the broad competitiveness of the product markets (goods and services) — that places the United States out by itself on the charts. It’s an outlier nation yet again, as it is on so many surveys and assessments. Neither fish nor fowl.

What is clear is that the remaining Big Five in the Anglosphere (UK, Canada, Australia, NZ, Eire) will struggle with their cultural predisposition to “fix” the product markets and penalize their overall economic productivity growth. The US market is huge and fiercely competitive — and manages to constantly find new areas where technology, technique and economies of scale can be applied. One look at eBay and Amazon.com confirms it. In many ways, the next largest economy (the UK) is very aware of these trends and routes to increased productivity but the political culture of Great Britain does not allow the nation’s government to extract itself from the product marketplace to the same degree.

As for India’s role in the Anglosphere, as mentioned above, I found Lewis’s book very sobering. India, short of some new kind of mathematics, simply cannot reach even middle-income per capita GDP within a century or two. Whether the intervening years bring a great exodus of Indian talent to the other Anglosphere countries — or some epidemiological catastrophe shrinks the population such that new economic rules can be instituted — it’s hard to read Lewis and come to the conclusion that India as we know it will fulfill any national role as broadly wealthy country in the near- or medium-term. Indian individuals and cohorts may be tremendously influential. The nation however, as it is currently organized, falls behind the rest of the Anglosphere (let alone the US) minute-by-minute.

It should be emphasized that Lewis himself is very cognizant of the importance of raising productivity levels around the world, if only from the perspective of global stability, while admitting that he was overwhelmed by the great practical divide that separates the Anglosphere, Europeans and Japan from the rest of the world. His research really suggests (as the ten points above indicate) that institutions such as the World Bank and IMF are still not grasping the cultural nettle in the developing world that inhibits productivity growth and therefore the accumulation of national per capita wealth.

As he notes, decades of international development efforts (let alone Christian missionary efforts) have created Third World cadres with explicit rationales for behaviour that intrinsically inhibits economic productivity. And we can see the same behaviour replicated across the Anglosphere itself to greater or lesser degrees. Have we reached a situation where nations are their own worst enemies? Big government and educated elites are hitting developing economies at the very point in time when they need the unusually high levels of productivity growth that can only come from unimpeded foreign direct participation in national economies. By and large, it ain’t going to happen. Which in turn suggests that some 22nd century William W. Lewis may well write a book on how little has changed on the per capita GDP curve during the 21st century. One hopes not, but the data in this book on 20th century progress is hard to deny.

–==–

Table of Contents

1 Findings: The Global Economic Landscape [1]

Part 1 Rich and Middle-Income Countries

2 Japan: A Dual Economy [23]

3 Europe: Falling Behind [50]

4 The United States: Consumer is King [80]

5 Korea: Following Japan’s Path [105]

Part 2 Poor Countries

6 Brazil: Big Government is a Big Problem [135]

7 Russia: Distorted Market Economy [166]

8 India: Bad Economic Management from a Democratic Government [197]

Part 3 Causes and Implications

9 Patterns: Clear and Strong [229]

10 Why Bad Economics Policy around the World? [257]

11 New Approaches [285]

12 So What? [312]

That’s fascinating about the 65 million Indians in the dairy farming business–I wonder, though, is dairy all they do, or are these farmers who also have one or two cows in addition to whatever else they raise?

When the distribution of wealth is so outrageously skewed (the three richest people in the world own more wealth than the GDP of the 40 poorest countries combined) an average per capita is not illuminating. The question is, what’s the bottom quartile of wealth; the middle half; the upper quartile; in Europe compared to the US? Most people in Western Europe could have a better standard of living than most of us, while per capita GDP is lower. In the US, while GDP has gone up, median income has remained the same for the past 20 years.

Anonymous:

-You are confusing wealth and income.

-Why is the distribution of wealth outrageous? What would be a non-outrageous distribution of wealth? How do you think the world would differ if such a wealth distribution existed?

Mankiw did a post relevant to this. Although there is more income inequality in the US than in Europe, higher average US income means that the poor in the US have similar real incomes to the poor in Europe. The difference? Above average and wealthy Americans are much richer.

http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2006/10/us-and-european-inequality.html

“Apart from the steel, automotive and electronic industries in Japan, and retail banking in the Netherlands, virtually no other nation on earth has more productive agricultural, industrial, and service sectors than America.”

I’m not sure what “electronics” refers to, but if you take the remaining industries, Autos, Steel and Banking you have two of the most unionized industries (steel, autos), two of the most regulated (autos, banking) and one of the biggest beneciary of tarriffs (steel.)

If we got rid of the tarriff’s, regulations and disbanded the unions we’d probably lead in those industries as well.

Another great post James. When are you yourself going to write a book instead of reviewing those of others, or have you already?

The power of compounding over time – we seem to be the beneficiaries of a long series of good investment decisions on what to buy, what to keep, and what to sell off. In some ways, the last is the most important. The best way to raise productive capital is to move it from an unproductive use.

“…what to sell off.” Mitch, agreed absolutely.

We’ve got good bankruptcy procedures. This is a huge advantage. Failed businesses can be sent to the slaughterhouse in a cold, efficient, orderly and non-violent manner. This something most other cultures don’t do well at all.

About poverty in the US vs other rich countries:

Prof Mankiw cites a paper by Smeeding and Rainwater that draws exactly the opposite conclusion from what has been stated here. They argue that despite higher mean income, the US has more poverty than Europe. (And wealth inequality and income inequality are of course closely related). Here’s the paper:

http://www.lisproject.org/publications/liswps/244.pdf

To sum up their conclusions:

“The United States has

one of the highest poverty rates of all the countries participating in the [study], whether poverty is

measured using an absolute or a relative standard for determining who is poor. Although the

high rate of relative poverty in the United States is no surprise, given the country’s well-known

tolerance of wide economic disparities, the lofty rate of absolute poverty is much more troubling.

After Luxembourg, the United States has the highest average income in the industrialized world…. yet it ranks third

highest in the percentage of its population with absolute incomes below the American poverty

line. The per capita income of the United States is more than 30 percent higher than it is, on

average, in the other ten countries of our survey. Yet the absolute poverty rate in the United

States is 13.6 percent, while the average rate in the other 10 countries is just 8.1 percent…

The relative size of the low-income population in the United States is larger than in other

rich countries for two main reasons: low market wages and limited public benefits.” They show that children and the elderly in the US are, in particular, much more likely to be poor than in W. Europe.

I’m not sure why, in fact, Mankiw drew his graph from these folks’ “Luxemburg Income Study”.

The elderly in the US are poor? Last I remember only about 15%.

They have enough money to go to the cas***inos. And they certainly have better teeth than Britain.

What age do they define “elderly?”

–Education is not the way out of the poverty trap. —

1. Get a HS education.

2. Don’t get married until after age 20.

3. Don’t have kids until after married.

That’s the secret of staying out of poverty, barring unforseen circumstances.

—-

I just read part of India are becoming less vegetarian. A theory is that they’re becoming more prosperous and can afford meat.

—

I should have added, maybe our “elders” are poor because they’re spending too much time in the cas***ino (for some reason, the filter doesn’t like that word) or there’s just too much to buy and do.

There’s lots of elderly driving big Lincolns and Caddys in the no state tax FL.

Just another argument to lower or erase corp. taxes and get tort reform. Then watch our possibilities.

However, Norway – don’t they get a lot of income from their natural resources??? It’s a shame we can’t.

“we seem to be the beneficiaries of a long series of good investment decisions”

Mitch, that’s true, but I think too many leftists would attribute our good fortune to luck or avarice.

As James’ peice points out, we made good decisions, or rather, we made better decisions than our global competitors only because competition forced us to.

Sandy P.’s observations would seem merely anecdotal but I suspect they are broadly applicable. For instance, census data indicates: Median net wealth peaked among householders aged 65 to 69. Widows who live by themselves & own farms, small businesses, or at least manage their husband’s pensions are often from families barely getting by during the widow’s thirties & forties, as they scrimped to pay off the mortgage, invest in their children & their pensions.

The observation that Europeans “feel” more secure strikes me as important & probably right. It also implies that we have made different tradeoffs & that we see the “good life” differently. Others tend to think we see the “good life” in terms of goods – and it is true, I have trouble seeing people with cell phones, multiple televisions, cars, etc. as “poor” in any historical sense. But I think we choose vitality over security – and there are places where some choices have to be made that prioritize these.

Anecdotes:

-I met an American guy who got an academic job in Sweden a long time ago. He married a Swedish woman and has children. He told me that he can’t leave Sweden, among other reasons because Swedish tax rates are so high that he has been unable to accumulate significant assets and is therefore dependent on the Swedish state for his retirement income. I don’t think he minds this situation, since he seems to have made a satisfying life for himself in Sweden. He has security of a sort. However, he lacks choices and in that sense is in a much different situation than are many Americans of similar age and professional achievements. Even Americans who have fewer talents than he does may have more opportunities, because of the more open and competitive nature of our society.

-A long time ago I visited relatives who lived on an Israeli kibbutz. In discussing kibbutz life they pointed out to me that the kibbutz took care of its members after they retired, and that someone who developed health or other problems and couldn’t work would always be taken care of. Moving forward to the present, my surviving relatives from that and another kibbutz have all left the kibbutz system. The kibbutz system, which for all the years was living off government subsidies, is now struggling and trying to compete in the market economy. The security of knowing that you would always be taken care of may not exist anymore, and even if it does it is decreasingly competitive with alternatives available to people in the profit sector of the economy.

The point of the study is that by being so pro-consumer accross all industries, the U.S. has been unmatched in productivity accross all industries; whereas, say Japan, while productive in a few key industries is completely ineffecient in the industries that make up the majority of its economy. According to the study, that and and only that seem to be the main thrust of difference between the US’s and other stong, but no quite as productive economies.

This pro-consumer bent helps the poor(er) because it provides them with much more purchasing power per dollar.

To be sure, India does face some significant challenges, but for those clamouring to get into China, I would advise that it represents a better alternative.

However byzantine their bureaucracy may be, India has gone a long way to clean it up. Also, being a parliamentary democracy, there is less likelihood of the government taking arbitrary action against foreign firms.

Goldman Sachs, in their BRIC discussion paper, pointed out that India suffers relative to China due to the amount of FDI. This is remarkable given that India’s capital markets are more mature and their loan failure rate is less than half the PRC average.

My worry is that investment in the PRC will become the undoing of many companies. Either through unilateral actions from Beijing, the trading band of the Yuan, or the number of bad loans that come to surface from their banking sector, or all of the above, it may become a bubble ripe for bursting.

I’d rather invest in India if I had a choice between the two populous neighbours…

Re: Smeeding on absolute poverty

In recent presentations, Smeeding has been a bit hesitant in how to interpret the absolute poverty measures. When questioned about them he conceded that the US has had — over a longer period of time — a larger pool of low-wage immigrants than Europe and that consumption and income figures track each other very poorly for the lowest quintile in the US. He agreed with someone’s guess that tracking US and European citizens and their children from the 1970s to 2000 (excluding immigrants) would probably not lead to such dramatic differences in absolute poverty. This suggests that part of the variance for the US comes from immigration as well as from high birth rates among the poor — which is consistent with the dynamic nature of the US economy — as well as with poor measures of non-wage income. He has been doing work on poverty which has equally large problems of interpretation. Mid-level Italians seem to have more wealth than Americans, but it is mostly in housing/land and is highly dependent on how that housing is valued (given that housing is not an internationally trade commodity).

“He has been doing work on poverty…”

I meant wealth, not poverty.

To add an anecdote: has anyone met a poor European or been to where they live? The next time you are in Paris, take an RER train to one of the famous banlieues where the riots took place (which killed three people nationally, by the way). Then visit a segregated urban housing project in the US or a rural trailer park….

And by the way, why is there this defensiveness about how great America is compared to Europe? Fifty years ago, we knew we were a great nation and didn’t carp against Europe. It seems to me itself a symptom of decline…

a comment: What exactly is your point? Fifty years ago the European press was not attacking us to the extent that it is now, so we were not as defensive. Ingrates.

I’ve been to those places in the EU and Eastern Europe. I tend not to sneer at them or at their American counterparts, because I come from a pretty poor rural background – my family lived in a mobile home for a few years when I was a kid, although it was on a wooded lot up in the Appalachian foothills, and not in a park. My grandparents’ house had no indoor toilet. We moved on and moved up, although in our particular case a knife fight at the roadhouse a little further up the mountain that left a neighbor missing an ear helped with the decision to get out of Dodge.

The attribute that separates American poor people from Europeans in my experience is where they are headed, not where they are. Even Americans whose work habits are so poor that you just know they are never going anywhere still have dreams of getting to a better place. The European poor I’ve met are just waiting for the next government handout. Not that a lot of American poor don’t have that attitude, too, but there are very, very few European poor who will move out of their socio-economic situation, whereas for lots of Southern people like my family, the trailer is only a stop along the way. That striving for upward mobility is less true in the American inner city, where European-style welfare programs have warped people’s thinking, but it’s still more true there than in any European (or Eastern European) slum.

I appreciate John’s experience that rural poverty can be accompanied by an all-American striving for something better, which is something I admire in American society even when it’s not fulfilled. However, blaming the devastation of the American inner city on a welfare mentality, as John implies in his last sentence, is blaming the victim pure and simple. He is aware that transfer payments to the poor are less here than in any of the other 11 industrial countries, and that most recipients of those payments are white and not inner city residents. Places like the South Bronx, the South and West Sides of Chicago, and inner city Detroit have few public services, massive unemployment, poor public transportation, poor schools, are often in proximity to toxic industrial areas, have dangerous public housing (unlike the ugly but livable housing in Western Europe) and serve as drug distribution centers for the largely white drug consumers in surrounding areas. What about this has anything to do with “European-style welfare programs”?