[Readers needing background may refer to the earlier members of this series, Don’t Panic: Against the Spirit of the Age, and Don’t Panic: A Continuing Series.]

Time is running out, the man explains, speaking calmly and confidently, in the manner of a university professor. A deadly disease, spread by primitive tribespeople through dead bodies, will kill vast numbers of Americans unless the Federal government uses its powers to stop it.

The man is Russell Eugene Weston Jr., a paranoid schizophrenic who murdered two policemen inside the Capitol building in the summer of 1998. He has been institutionalized ever since.

As I write this, the most widely-read individual blog in the English-speaking world, written by a genuine university professor, is infested with (invariably pseudonymous) commenters not readily distinguishable from Weston; we can only hope that none of them will act on their impulses as he did. Vast majorities of Americans have expressed sympathy for drastic measures to counter the supposed threat from EVD. Fortunately, and as pointed out by Jonathan in this forum, markets remain unperturbed, which you would think would tell conservatives something (it probably would if the current President were a Republican). But the possibility of thousands of deaths among people choosing to drive rather than fly, and far greater numbers among those who choose to avoid hospitalization for a variety of ailments, remains.

How to characterize the range of reactions among Americans, many of them bizarre to the point of the delusional (cf Naomi Wolf), in a way that imparts understanding and improves our tactics for properly assessing and responding to the threat if there is one at all?

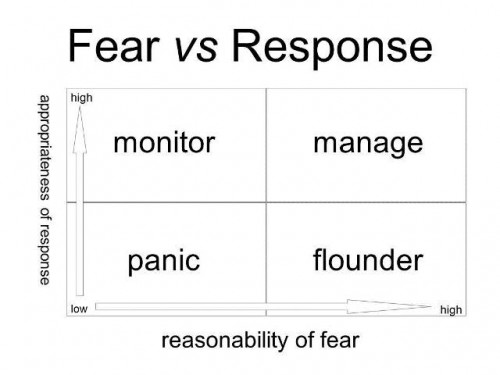

I like quadrant diagrams, which probably says at least as much about me as it does about any given situation I apply them to. I do try to at least get the presentation right, by putting the independent variable on the x-axis and the dependent variable on the y-axis. So here’s one:

As I see it, there are four basic kinds of fear-prompted reactions, the independent variable being the reasonability of the fear itself and the dependent variable being appropriateness of the response to it. We of course like to think that we respond in an appropriate, linear fashion to alarming stimuli, but having recently heard of (for example) people changing clothes because they just passed through DFW airport, I think I know better. A reasonable fear is one involving a high-magnitude negative risk event (threat), magnitude being probability × impact. An appropriate response is one that best allocates resources, including marginally available time, emotional energy, finances, and physical energy, to effective management of the threat.

The immediate case is squarely in the panic quadrant: a wild overreaction to a threat which is itself statistically comparable to being struck by lightning extreme low probability but high impact. Behaviors, as noted above, range from the merely absurd to ironic exposure to far greater levels of negative risk, most acutely for those needing hospital care at a facility whose resources have been diverted to an Ebola false alarm.

A proper answer to those behaviors is simply to back off and shift things upward into the monitor quadrant. At the individual level, for EVD this means continuing to pay attention, even after the midterm elections this Tuesday (after which I expect the amount of frantic commentary on Ebola to plummet), although probably not much more attention than you would to the risk of being, as already mentioned, struck by lightning. If you still feel like you need to do anything at all, keep an eye on airline stocks and ignore everything else. Institutionally, monitoring implies relatively easy testing, and various devices have preliminary regulatory approval.

Now suppose the fear becomes reasonable but our responses don’t improve. Instead of EVD, which isn’t especially easy to catch, and is spreading in an environment differing drastically from the US one without potable water or reliable electricity, with far poorer nutrition, probably with high prevalence of anemia and hypertension, almost certainly with high levels of helminth infections, and notoriously lacking in medical resources or, indeed, functioning institutions let’s imagine, as posited in my list of fears in the first post in this series, a novel viral pandemic. Something with a worst-case combination of a long period of subclinical infection overlapping with communicability, plus high mortality in the clinical infection phase. It shows up in many places simultaneously, urban and rural, all over the country, so ring vaccination is futile. Based on the noisier reactions to Ebola, I would expect us to at least temporarily be in the flounder quadrant, flopping around in a metaphorical basket of delusional conspiracy theories, useless home remedies, and often-fatal political/economic decisions. This situation might obtain even if the event were an all-too-straightforward bioterror attack with Variola major virus, which has been killing people since the dawn of civilization and was not fully controlled until the 1970s.

How to ascend into the manage quadrant, where even severe threats are handled properly? Institutionally, we will need both inexpensive testing inexpensive in all four of the senses of Margin, referenced above, which is to say quick, (relatively) non-stressful, cheap, and easy but also good process design, as noted in the second member of this series, to prevent bottlenecks at critical facilities. To the extent that institutional responses emerge from individual behavior, however, we all need to tighten up on some things, starting with attitude. Running and hiding will only make things worse, and a careful evaluation of our fears is the first step toward cultivating a truly constructive apprehension. Most of all, be deeply circumspect about consigning more power to the State; it has a way of accumulating.

Don’t be Weston. There is no Black Heva.

Is this a pitch for abstaining from quarantines? Just because America is less vulnerable, doesn’t mean that cases here don’t consume significant resources (hospitalization, transport, dialysis, alternate housing, replacement income, tracking personnel, hazardous waste disposal, and hazmat personnel……); resources that would be far better and more effectively spent at the epicenter in W Africa.

Did you read the earlier post where I discussed the risk of diverted medical resources?

What is EVD? Is it a new acronym for Ebola?

Another dimension to fear is whether it is singular and random or is it likely to extinguish your close DNA group?

The former, like lightning, is individualistic and knows out only one carrier of the family DNA.

The latter is more dangerous to one’s DNA batch since while the odds over a large population might be the same, killing you and your genetic relations means the end of your genetic inheritance.

Mr. Manifold,

Do you have personal experience including either failure or success of your Quadrant? I mean personally, when death is present and looking for victims. There’s game theory, then there’s Life.

Of course the experts aren’t trusted, people don’t want to suffer the tortures of Africa as inflicted by experts, such as many deaths from infected needles, something WHO has known is infecting a new child every 20 seconds since the 90s, but did not act or allow action [1 time use needles] for fear of stopping the precious programs.

Do go have a whirl at your Quadrant, let us know how it passes the test of life and death.

Traffic stats: Whenever someone mentions traffic deaths know that they mean harm.

The DNA comment is fascinating.

“…having recently heard of (for example) people changing clothes because they just passed through DFW airport…”

And?

I view that as horrible as someone deciding to wash their hands an extra 5 seconds because they passed through DFW. The cost of the action they are taking is minimal; Hell, if I arrived after an overseas flight, then I might want to change clothes anyways.

A crazy guy once got upset about a non-existent disease, so don’t ever be concerned about a deadly epidemic that could, through mismanagement, be severely disruptive and kill more people than necessary. Got it.