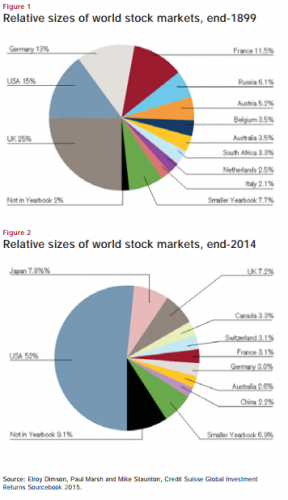

Every weekend I read Barry Ritholtz’s recommended reading and there are a lot of gems in there. Recently he posted this Credit Suisse graphic about markets at the turn of the 20th Century by market share and compared it with 2014 on the topic of global equity investing.

In his article he mentioned the fallacy one might fall into as a UK equity investor in 1899… why bother investing in the USA when the UK market is so much larger? And then this line of thought ends up missing the huge growth in US market share over the next century.

However, the real issue here isn’t the relative change in market share by the different countries; it is the fact that almost all of these markets were entirely extinguished at one time or another by political, economic or military events that wiped out the investors.

The implicit “long run” theory of investing can be pithily summarized as “leave in your money indefinitely, keep investing, and it will all work out for you”. Sure, the USA had a near-death experience in the 1920s-1930s with the Great Depression, but if you would have been able to hang in there, long term gains would have more than made up for any of those losses!

But this model doesn’t work out if you are completely liquidated by a discontinuous event somewhere along the line. There is no ability to recover from lows if your equity basis is driven down to zero. The only way to survive in this sort of long term model is to pull out entirely from markets at some point, put your capital in a different market, and return to that market when those calamitous events have passed. This is at complete odds with the “long run” model that I vastly simplified in the previous paragraph.

It is completely obvious but that German market share from 1899 to 2014 didn’t “drop” from 13% to 3%… that is a statistical artifact because all of the German equity investors were wiped out by war and then a new class of equity investors came to take their place under the “German” name. The pre- and post-war markets shared nothing in common from a continuous-investor perspective, especially if you were a US resident attempting to invest in Germany. All of these markets with the exception of the US, UK and parts of the British empire (Canada, Australia, South Africa) had “liquidation” events that took out all the investors and in 1940 before the US entered WW2 even the Commonwealth had a near-death experience.

There is no “long run” model as I described above for ANY significant market with statistics except the US and UK yet this fact is rarely mentioned alongside the statistics. The only way to be a global investor with a mega-long horizon (decades) is to try to get in and out of these markets before “wipe out” events occur, of which there are many, including:

– Currency Events – Greece is essentially going to wipe out their equity markets (it already has mostly happened) if they leave the Euro, and there will be a new group of investors that would take the place of those that were liquidated

– Military Events – at some point US investors likely will be pushed entirely out of Russian markets if our military escalation continues, and this will be linked with currency market changes as well as commodity market changes and nationalizations

– Commodity Market / Nationalizations – in Latin America today we see nationalization of assets which can be closely linked with commodity price movements (oil price drops) as well as distortions of their currency markets

To use a bad sports analogy, it is as if we base all of our predictions and records on the NY Yankees and don’t talk about all those teams that started, folded, and moved since the 1927 Yankees fielded arguably the most dominant team of all time relative to competition. We don’t talk about the Montreal Expos, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Washington Senators, etc… and we can learn just as much, if not more, by looking at the dead-ends and how they ended up failing as we can by following the most successful teams and thus celebrating their great fortune as the de-facto norm.

Cross posted at LITGM

There is a school of thought that German investors moved assets to Argentina and after the war, moved them back to Germany and that this was a good part of the “Wirtschaftswunder.”

I don’t know a good source for this theory but I have read about it. Any thoughts ?

I think we are headed for an “inflection point” with our economy. I wish I had bought gold in 1997 but am starting to think it is getting time. I did buy in 1978 and sold a year later for 100% profit.

“Greece is essentially going to wipe out their equity markets (it already has mostly happened) if they leave the Euro”

Greece has some options that Germany and the EU don’t want anyone to know about.

OK, here’s the obvious solution: Greece can print up small-denomination zero-coupon bearer bonds, essentially IOUs. They say “The Greek government will pay the bearer 1 euro on Jan 1 2016.” Greece can roll them over annually, like other debt. Mostly, they would exist as electronic book entries in bank accounts, but Greece can print up physical notes too.

Basically a de facto alternative virtual currency, backed by the Euro. Actually, since the Euro will soon go the way of all those “prior” markets you mention, they would be better off switching to bitcoins or some other digital alternative or just allow circulation of all currencies.

Good post. Some thoughts:

-There was a “UK” in 1899?

-Survivorship bias is a common source of error in financial market analysis. Most companies don’t survive in business for decades. Any long-term investment analysis that looks only at companies that remain in existence for the entire period tested will overstate returns. National markets, as supersets of individual stocks, are also subject to survivorship bias.

-“Buy and hold” as investment strategy is marketing spin. An individual stock might appear to have great prospects even when the market as a whole is at risk due to the possibility of extreme political or other non-market events. Anybody who is serious about trading or investing has a way to control that risk, including by liquidating individual positions and even exiting all positions when non-market risks grow to unacceptable levels.

-Theories are fine but losing money is an absolute constraint. You can’t invest if you lose your capital. If you lose half of your capital you need to make a 100% return merely to get back to even. Even if you lose a mere 1/3 of your capital you need to generate a 50% net return to break even. Doing that isn’t easy. The prudent investor will have in mind a loss level on his total equity at which point he will liquidate all positions and reevaluate.

-Currency devaluations, capital controls, market shutdowns and other consequences of natural disasters, wars and other extreme political events can make it impossible to cash in your investments even if you are clever enough to try to do so before price declines wipe you out. There’s a lot to be said for spreading your investments between different countries as well as asset classes before you need to.

-US investments are not invulnerable to any of these considerations.

“US investments are not invulnerable to any of these considerations.”

Even now, I am skeptical that the US stock market ever recovered from 1929. Think $20 gold and the Dow high in September 1929.

Certainly, it is an inflation hedge.

Excellent post, Carl.

The world is a much riskier place than merely looking at the anomalous unbroken continuity of the US stock market would suggest.

“There was a ‘UK” in 1899?”

There has been a United Kingdom since 1707. The Act of Union created a new entity out of the previously existing kingdoms of England and Scotland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

I am not sure when it became common usage to refer to what is now the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as “the UK.” Certainly after the Second World War.

I stand corrected.

Did an Ngram on United Kingdom, UK, Britain, Great Britain and England. United Kingdom takes off after 1945 and UK 1960. But what is very interesting is that use of Great Britain collapses after 1940 and Britain doesn’t do much better. England, by far the most frequently used term, began falling in use in 1880 and has been on a steady decline until 2003 when its use began to climb. In the mid 1990’s England appeared about 50% more often than Britain, Now it appears 100% more often.

}}} In the mid 1990’s England appeared about 50% more often than Britain, Now it appears 100% more often.

Proof that “There will always be an England…” :-D

Check out the book “Triumph of the Optimists” by Dimson, Marsh,and Staunton for an overview of world market history.

I am honored to get the “deep thoughts” tag :)

Watching Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, on Charlie Rose.

He talks about countries that are “on” or “off” the grid… the same types of analysis that we list above how capital is destroyed, and mentions latin america and Russia and soon-to-be-Greece if they leave the Euro.