In my post Technology in 1925, I mentioned the Bartlane process for transmitting news photographs via undersea cable. The way that this process works is so..so…the words ‘elegant’ and ‘baroque’ both come to mind..that I thought it deserved its own post.

Transatlantic cables had been around since the 1860s, originally handling transmissions in Morse Code or its cable variant. By 1925, teleprinter transmission thru the cables was increasingly common. Bandwidths had increased but were still quite limited–a maximum of 25 to 40 characters per second, usually multiplexed into multiple slower subchannels. These cables were strictly for telegraphy: voice telephony under the Atlantic was still many years away. News stories could be transmitted under the ocean almost instantaneously, but the accompanying photos would take a week or more: obviously there would be commercial value if the photos could be transmitted by cable as well.

So how was telegraphy married with photography?

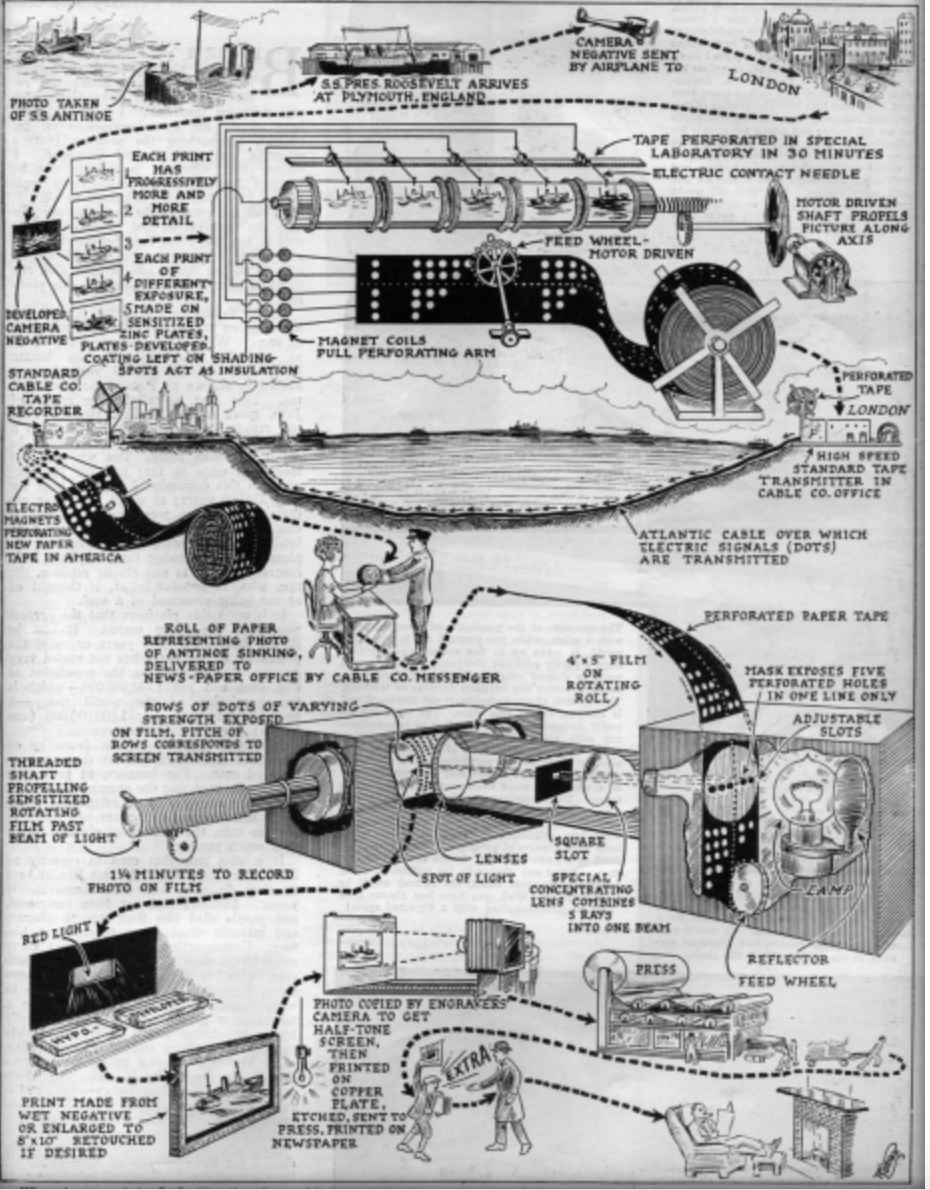

The Bartlane process (Bartlane comes from the names of co-inventors Maynard McFarlane and Harry Bartholomew) starts with analog-to-digital conversion of the filmed image (although neither ‘analog’ nor ‘digital’ were terms in common use at the time)..varying shades of gray at particular points in the negative (‘pixels’, in our terminology) are captured as combinations of holes punched into a paper tape. The completed tape is sent to the cable office where it is transmitted using standard cable transmission equipment..simultaneously punching a duplicate tape at the other end of the cable. The received tape is then run through a device which recreates the original picture…with quality limited by the density of pixels and the number of shades of gray that the equipment can handle.

In its original 1924 released form, the Bartlane system contained no electronic components at all–it was strictly mechanical, electrical, and optical. How did that work?

Like this…

Five thin plates, each coated with photosensitive insulation, were exposed to the film negative for varying amounts of time. The plate having the shortest exposure time records only the black tone in its insulated areas, the next plate insulates the dark and gray areas, and so on until the last plate, with the maximum exposure, insulates all areas except white.

The plates are wrapped around a rotating cylinder which is scanned helically. Each plate is electrically read by a contact finger, and those fingers are linked to a punched paper tape device. For each picture element, from zero to five holes will be punched (in parallel) into the paper tape, which is then advanced for the next pixel. The number of holes will be punched in any position on the tape will depend on how light or dark the corresponding point on the photo negative is.

When the image conversion is complete, the tape is taken to the cable telegraph office and transmitted using standard cable tape transmission equipment. At the receiving end of the cable, another paper tape is punched, duplicating the one that was transmitted. The tape is then run through an optical system which combines light shining through all 5 of the parallel holes in each position of the tape. The more holes are punched, the more light will be focused on the selected spot on the film–which continuously changes as the tape and the film both advance. The film is then developed and made printable thru the usual photo engraving process.

The system as originally released could only quantize the pixels into five levels, which was less than required for really good image quality. McFarlane said in a 1972 retrospective that the five-prints-plus-electrical-contact-fingers approach had been used because reliable photoelectric sensors were not yet available: by 1927, an improved Bartlane system was introduced which did use such sensors, along with vacuum tubes for amplification, plus a chain of sensitive relays to code the image: it could capture 15 levels of gray. Here’s an image after transmission with the original 5-level system and a slightly later image transmitted with 15 levels. Electronics, even though a small part of the revised system, made the difference.

In his 1972 article, Bartlane co-inventor McFarlane said that creating the sending tape from the film took about 40 minutes and transmission of that tape over the cable would take 45 minutes to 1 hour. (It was entirely possible to cut the tape into segments for simultaneous transmission over multiple channels, and this seems to have been the usual practice) Transmission was not cheap: a standard 5×4 news photograph would be represented by 72,000 pixels, each punched into a row of holes in the tape, in the same way that a single character of a normal telegram would be punched. If a typical cablegram was 15 words and we use 6 characters per word, that would be 90 characters…add 10 more at a guess for message header information for a total of 100 characters per telegram. That implies that a single photograph would require the same cable capacity as 720 normal text cablegrams.

McFarlane in 1972: “Seated in a comfortable armchair watching live television from the moon, it is hard to believe that in the early 1920s it took the better part of a week or more to get news pictures across the Atlantic. The Bartlane cable picture transmission system reduced this to a matter of 2 or 3 hrs to enable publication of pictures with the news they represented.”

What was the impact of fast transatlantic picture transmission?

First, the effect on the media of the time: The ability to print timely pictures from far away would have improved the competitive position of newspapers relative to that of radio–until television was introduced, adding moving images to radio and greatly reducing the influence of text.

From a broader social standpoint: Telegraphy had already made the world seem smaller and focused people’s attention much more on events beyond their traditional horizon: cable photography surely accelerated this trend and later technologies would accelerate it still further. CS Lewis saw this broadening of horizons as mainly a bad thing: do you agree?

I remember as late as 1989 during Tiananmen Square, when all the Western reporters were confined to their hotels and denied wire facilities, they had to physically smuggle photos and tape out for publication.

By the way, that 5 channel tape used the Baudot encoding scheme. this is where the term baud rate comes from, meaning characters per second.

Unbeknownst to most people, paper tape was everywhere, once.

And then suddenly it was nowhere.

I am personally glad it’s gone.

ed in texas….I bet that somewhere there’s an NC machine still running off paper tape.