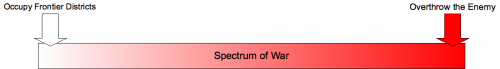

Clausewitz teaches the faithful that war is a spectrum. He identifies several points on this Spectrum of War. Here’s two from his note of July 10, 1827:

War can be of two kinds, in the sense that either the objective is to overthrow the enemy—to render him politically helpless or militarily impotent, thus forcing him to sign whatever peace we please; or merely to occupy some of his frontier districts so that we can annex them or use them for bargaining at the peace negotiations…the fact that the aims of the two types are quite different must be clear at all times, and their points of irreconcilability brought out.

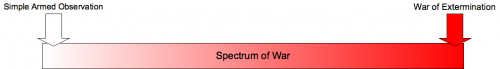

Two from Book 1 Chapter 1:

Generally speaking, a military objective that matches the political object in scale will, if the latter is reduced, be reduced in proportion; this will be all the more so as the political object increases its predominance. Thus it follows that without any inconsistency wars can have all degrees of importance and intensity, ranging from a war of extermination down to simple armed observation.

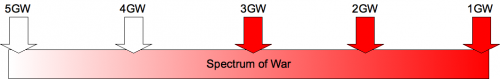

Five from Book 1 Chapter 2:

We now see that in war many roads lead to success, and that they do not all involve the opponent’s outright defeat. They range from the destruction of the enemy’s forces, the conquest of his territory, to a temporary occupation or invasion, to projects with an immediate political purpose, and finally to passively awaiting the enemy’s attacks.

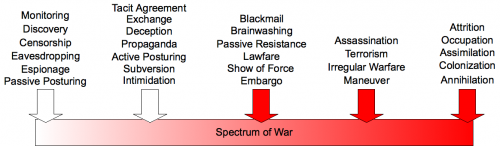

Being human creates even more points on the Spectrum of War:

Any one of these [means] may be used to overcome the enemy’s will: the choice depends on circumstances. One further kind of action, of shortcuts to the goal, needs mention: one would call them arguments [against the man]. Is there a field of human affairs where personal relations do not count, where the sparks they strike do not leap across all practical considerations? The personalities of statesmen and soldiers are such important factors that in war above all it is vital not to underrate them. It is enough to mention this point: it would be pedantic to attempt a systematic classification. It can be said, however, that these questions of personality and personal relations raise the number of possible ways of achieving the goal of policy to infinity.

What separates one point on the spectrum from another is the concentration of violence and effort. A war of annihilation, as Clausewitz points out, will involve more effort than simple armed observation, occupying a slice of territory, or even destroying the enemy’s forces. The Spectrum of War is useful because it presents war as a range of choices from which policy can select, subject to the constraints of available resources. This range of choices is best represented as a series of representative points on the spectrum. This can take any form that will communicate the point effectively:

Or another:

Or a more useful range of choices:

It is useful to view the Spectrum of War as if it was controlled by a knob. Turned one way, policy can rationally ratchet up the violence. Turned another, it can ratchet it down. The regulating mechanism is the political object of the war, subject only to the BIG ifs of chance, passion, and friction:

When whole communities go to war—whole peoples, and especially civilized peoples—the reason always lies in some political situation, and the occasion is always due to some political object.

Notice that Clausewitz doesn’t restrict his discussion to states, as is often alleged. Even “non-state actors” are communities and communities all have political objects:

War, therefore, is an act of policy. Were it a complete, untrammeled, absolute manifestation of violence…war would of its own independent will usurp the place of policy the moment policy had brought it into being; it would then drive policy out of office and rule by the laws of its own nature, very much like a mine that can explode only in the manner or direction predetermined by the setting…

Real war is different:

[War’s] violence is not of the kind that explodes in a single discharge, but the effects of forces that do not always develop in exactly the same manner or to the same degree. At times they will expand sufficiently to overcome the resistance of inertia or friction; at others they are too weak to have any effect. War is a pulsation of violence, variable in strength and therefore variable in the speed with which it explodes and discharges its energy. War moves on its goal with varying speeds; but it always lasts long enough for influence to be exerted on the goal and for its own course to be changed in one way or another—long enough…to remain subject to the action of a superior intelligence.

Clausewitz, however, gives us a caveat:

This…does not imply that the political aim is a tyrant. It must adapt itself to its chosen means, a process that can radically change it…

This point about adaption must be reiterated:

If the p0litical aims are small, the motives slight and tensions low, a prudent general may look for any way to avoid to avoid major crises and decisive actions, exploit weaknesses in the opponent’s military and political strategy, and finally reach a peaceful settlement…But he must never forget that he is moving on devious paths where the god of war may catch him unawares. He must always keep an eye on his opponent so that he does not, if the latter has taken up a sharp sword, approach him armed only with an ornamental rapier.

But the point remains:

[T]he political aim remains the first consideration. Policy, then, will permeate all military operations, and, in so far as their violent nature will admit, it will have a continuous influence on them.

The combinations of means are endless. Says Master Sun:

What enables an army to withstand the enemy’s attack and not be defeated are unorthodox and orthodox maneuvers. The army will be like throwing a stone against an egg; it is a matter of weakness and strength.

Generally, in battle, use the orthodox to engage the enemy and the unorthodox to gain victory. Those skilled at unorthodox maneuvers are as endless as the heavens and earth, and as inexhaustible as the rivers and seas.

Like the sun and the moon, they set and rise again.

Like the four seasons, they pass and return again.

There are no more than five musical notes, yet the variations in the five notes cannot all be heard.

There are no more than five basic colors, yet the variations in the five colors cannot all be seen.

There are no more than five basic flavors, yet the variations in the five flavors cannot all be tasted.

In battle, there are no more than two types of attacks:

Unorthodox and orthodox, yet the variations of the unorthodox and orthodox cannot all be comprehended.

The unorthodox and the orthodox produce each other, like an endless circle.

Who can comprehend them?

The need for such range is ultimately dictated by the multitude of political objectives to pursue. War, as an instrument of policy, must be equally varied:

To think of these shortcuts as rare exceptions, or to minimize the differences they can make to the conduct of war, would be to underrate them. To avoid that we need only bear in mind how wide a range of political interests can lead to war, or think for a moment of the gulf that separates a war of annihilation, a struggle for political existence, from a war reluctantly declared in consequence of political pressure or of an alliance that no longer seems to reflect the state’s true interests. Between these two extremes lie numerous gradations. If we reject a single one of them on theoretical grounds, we may as well reject them all, and lose contact with the real world.

War, subject to unequal distributions of power, passion, chance, and friction, offers a wide range of fare to the discriminating policy maker of taste.

A war of annihilation, as Clausewitz points out, will involve less effort than simple armed observation, occupying a slice of territory, or even destroying the enemy’s forces

Shouldn’t this be: involve more effort?

Indeed it should and now it does.

This post has been linked for the HOT5 Daily 1/17/2009, at The Unreligious Right

“War, subject to unequal distributions of power, passion, chance, and friction, offers a wide range of fare to the discriminating policy maker of taste.”

It also offers horrendous risks, while presenting an enticing mask of simplicity. In war everything is simple. That simplicity beckons to the policy maker, beset by complexity. Draw the sword, cut the knot, unify the people, win a victory, reestablish the regime on the blood of its enemies.

Yet everything is difficult in war. The very aim and purpose of the war, as the political leadership first imagined, warps and dissolves and hardens into new and unexpected forms. Fortuna turns her face away, and Nemesis offers her unwanted embrace.

War as a means to a policy goal turns out to be not a strong medicine but a lethal poison. It is so easy to get it wrong. It is so easy to send the army out, so hard to get it back with anything worth having, and the dead stay dead.

The first and highest self-discipline of the politician is to eat as little as possible from the buffet. Just as much as needed to sustain life, and not to be greedy. Some of those chocolate bon bons are laced with arsenic.

The elasticity of the term “war” is problematic. I and other commentators sometimes use it to refer to a wider spectrum of conflict than is supported by the conventional use of the word. Most people use it to discuss merely military confrontation. Clausewitz probably confined his use of the term war to military confrontations though there are hints that his thinking may have been expanding the spectrum of war beyond that. Perhaps we need better terms and concepts to discuss the gray region on the spectrum that falls between war-war and jaw-jaw since the majority of Great Power conflict since 1945 falls within that range and this nation is still poorly equipped for it in comparison with some other Powers.