Nisbett, R.E., Intelligence and How to Get It: Why Schools and Cultures Count, Norton, 2009. 304 pp.

[The publisher kindly provided a copy of this title for review]

Warning: 10,000+ words.

One of my side-interests is cognitive psychology, particularly cognitive biases in medical decision-making. Back in 2006, I stumbled over some research on how Asians and Westerners place very different emphases on objects when evaluating the world. The material was intriguing enough that I bought and cb reviewed) a copy of U Michigan social psychologist Richard Nisbett’s The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently…And Why (2003). Since then I’ve been doing a lot of reading on the history of science in East and West, and I found “Geography” very useful as a basis for thinking about past and future trends in global scientific culture. The subject showed up again indirectly in a cb review of Shutting Out the Sun.

My purchase of “Geography” earned me a pre-publication nudge from Amazon on the Professor’s latest book, which is different in subject matter from his earlier publication. Intelligence is a cognitive/social psychologist’s look at the educational and social environment leading to success in current American culture. It appears to be a plain-language summary of his NIH/NSF-sponsored research work on IQ/race and education. A less sexed-up title for the book might therefore be “The Role of Environment in American IQ and Accomplishment.”

Needless to say, the topic is massive so Intelligence spends a great deal of time recounting earlier research on the topic of IQ and race, academic achievement, career accomplishment, and the success of American secondary educational programs. In its academic variant, my guess is that the material was larded with footnotes and statistical detail. In Intelligence, the author take pity on the reader and adjusts the book’s content to describe research in plain English, and the impact or influence of potential activities on IQ scores in terms in of SD (standard deviation) or percentiles of student achievement. Appendices handle statistical definitions, a professional-level discussion of race and IQ, and a consideration of multivariate analysis. As noted, however, the book covers at lot of territory so my goal in this review is to mention the book’s topics (to tweak reader interest) rather than try to reiterate the author’s careful summaries and lucid assessments of the scientific literature. In other words, don’t take my word for it when it comes to the subtleties of research on particular subjects. Read the original, and the underlying articles.

The challenge, as with all social science research, is identifying the “confounding factors” that can muddy the results of research on IQ and subsequent individual success. The effective use of “controls” in a research program will improve confidence in the results. Otherwise, scientists are comparing apples and oranges without reaching any useful conclusions. Nisbett goes out of his way to give a sense of whether the research he reviews is misguided, inadequate, or merely suggestive without sufficient followup.

The Acknowledgements section of the book mentions John Brockman and Katinka Matson. This is a very good sign.Those two individuals are literary representatives for a stellar cast of scientists currently writing for the general public. Intelligence, despite being an overview of a vast amount of social science research, is very well written and edited. You’ll not find a better use of introductory, summary and concluding materials in each chapter to keep the reader oriented and motivated.

Table of Contents

1 Varieties of Intelligence [1]

2 Heritability and Mutability [21]

3 Getting Smarter [39]

4 Improving the Schools [57]

5 Social Class and Cognitive Culture [78]

6 IQ in Black and White [93]

7 Mind the Gap [119]

8 Advantage Asia? [153]

9 People of the Book [171]

10 Raising Your Child’s Intelligence … and Your Own [182]

Epilogue What We Now Know about Intelligence and Academic Achievement [193]

Definitions and Limitations

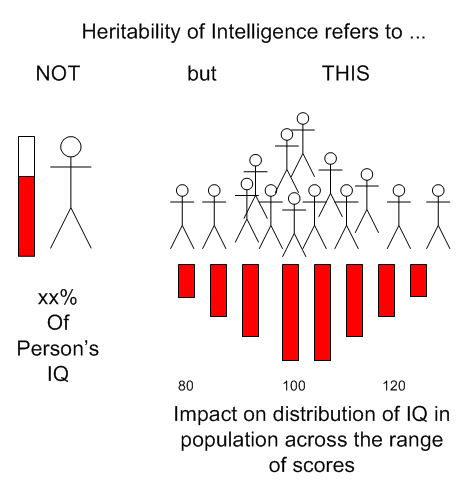

First off, the reader needs to understand that when scientists talk about the heritability of IQ, they aren’t talking about the percentage of any particular individual’s IQ that is controlled by genes. Instead, they are describing the distribution of IQ scores for a specific population. Differences in distribution between men and women, between ethnic or occupational groups, or within families would be example populations. The focus of this book is the American population generally, and different ethnic and socioeconomic status (SES) groups specifically.

Chapter 1

(Varieties of Intelligence) kicks off with a review of the role of IQ testing and its relation to scholastic and real-life accomplishment. The different definitions of intelligence are discussed. The most widely used definition of intelligence identifies two components: fluid intelligence (logical/analytical thinking) and crystallized intelligence (facts, step-by-step practical knowledge). These two kinds of intelligence seem to map most successfully to discrete brain function. The former capacity tends to level off in adulthood. The latter may increase throughout life. Recently, the term “intelligence” has been poached to describe other skills and attributes. Nisbett briefly evaluates whether such an expansion accurately mirrors intellectual capacity and sets the stage for a more traditional, but workable, definition.

The author notes that socioeconomic status (SES) tends to trend well with IQ. People with higher incomes tend to have higher IQs. That confirms the pattern that higher IQ has a “multiplier effect” on academic success and occupational achievement. Teasing apart the role of genes, specifically, in the IQ of particular occupations or social classes is the core issue addressed by Intelligence in the many pages that follow.

“Higher socioeconomic status of parents is related to educational attainment of the child, but higher-socioeconomic-status parents have higher IQs, and this affects both the genes that the child has and the emphasis that the parents are likely to place on education and the quality of the parenting with respect to encouragement of intellectual skills and so on. So statements such as “IQ accounts for X percent of the variation in occupational attainment” are built on the shakiest of statistical foundations. What nature hath joined together, multiple regressions cannot put asunder.” p.18

Teasing out the role that family environment has on IQ, distinct from the genetic variance in IQ within families (or between families) can identify not only the role of upbringing but the multiplier effects that determine how siblings, raised in the same environment, can have very different incomes & social outcomes affected specifically by their IQ. Nisbett makes an important point. If all IQ heritability research is undertaken within a relatively narrow range of SES, or depends on small pools of people, conclusions about the role of genes and environment will be inevitably skewed. It’s important that the research on IQ aggressively seek out data from as many environments and as many different types of people (from the very young to the very old) as possible.

Chapter 2

(Heritability and Mutability) takes a very close look at the statistical research associated IQ and race … and seeks to tease out the role that environment and socioeconomic status (SES) has on IQ as a child grows to adulthood. The author admits that this is the most intellectually challenging chapter of the book but does a good job of presenting the arguments in a methodical manner.

It’s been widely proclaimed, and largely assumed that IQ is “75-85% heritable” … that is, the particular distribution of IQ for the general population (averages, means, modal distribution, etc.) is mostly determined by genetic inheritance. Nisbett describes this as the “heriditarian” viewpoint, and it dominates general scientific received wisdom to this day. Any influence on IQ or its growth that is environmentally determined is largely assumed to disappear entirely by late adolescence. In contrast, the “environmentalist” viewpoint holds that IQ distribution in the general population is controlled by genes less than 50%, that IQ growth can be influenced much earlier and much later than traditionally assumed. Nutrition, perinatal health/prematurity, home life, education, and experience are all considered to have direct measurable impacts on IQ growth, IQ sustainment, and subsequent application of that intelligence to academic and occupational achievement.

We do know that there is roughly a 12-18% difference between the average IQ of high SES populations (the top third) and low SES populations (the bottom third). Even so, there may also be a 15-25% differences between the IQ of specific children within or across families in the same SES. Differences in environmental influence on IQ have been assumed to be nil after childhood and therefore not influential on adult life. Birth order, for example, may have a role in childhood development but the hereditarians would suggest it has very little adult impact on IQ.

Nisbett reviews the scientific foundation of the estimates on the role of genes by looking more closely at the research conducted 40-50 years ago which largely focused on adoption studies (kids from the same parents raised in different families) or twins studies (identical [monozygotic] twins raised in different families). The results of these studies suggested very little difference in IQ by adulthood for these study subjects. Confirmation of genetic influence on IQ … or evidence of research “confounding factors”?

Nisbett notes that not only are the number of study subjects very limited (N=?), but the controls to eliminate the role of environment were very poorly evaluated. For example, twins may share extensive uterine and post-natal environments before leaving the parental home. And when twins, or non-twin children, are re-located they often move to relatives or families with a predisposition toward adoption. And when science looks more closely at those adoptive families they find a few things. Firstly, those families are quite similar (i.e., non-randomly) to the birth family. And secondly, the families with a predisposition to adopt are largely middle or high SES and have parenting skills well above average (as measured by indices such as HOME – Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment . Finally, researchers found that middle class twins are logistically easier to study … so they inadvertently focused on families where the range of family/schooling environments was unusually narrow and generally quite positive.

In other words, the scientific basis for the heritability of adult IQ has been inadvertently reinforced by major research design flaws. The environments that children were born into and raised in were not randomly chosen, nor were they methodically controlled. If you move a child from a home and into a largely identical home, it’s not surprising that you’ll not spot any environmental impact on IQ. The more similar the environment, the less that its impact on IQ across a population will be accurately measured. Heritability will be measurable only when other externals are measured and controlled. Within SES classes, similar research challenges await. Genes affect IQ .70 standard deviations (SD) of IQ amongst the upper class and .10 SD in the lower class. Why? Because the range of home environments in the two classes are dramatically different. From largely good to excellent (in the upper class) to “quite good to pathological” in the lower class.

Fortunately, there is some research that attempted to randomize the impact of environment on IQ and IQ growth. A French study which didn’t constrain the SES of adoptive homes found a difference average IQ of 12 points between children raised in low SES homes and high SES home. Adoption, generally, seems to offer an IQ improvement for children-at-risk … but the increase is 8 points when adopted by a low SES family, 16 points when adopted by a middle SES family, and 20 points when adopted by a high SES family.

Such numbers are non-trivial when one considers that distinctions between average IQ for working, office, and management/ professional classes are often measurable in 10 point increments. An indirect confirmation of the role of environment in IQ also comes from the fact that there is a poor correlation between adoptive parent IQ and adoptive kid IQ. If environment quality has a major impact, then an adoptive parent’s IQ (distinct from their parenting skills!) may only play a small role on an adoptive child’s IQ growth.

Nisbett wraps this chapter with some references to very recent science books for the general public that largely accept at face value that IQ is overwhelmingly governed by genes … just as it was proclaimed in the Bell Curve 15 years ago. In a final point, Nisbett notes that there’s no known inherent limit on the mutability of IQ if the role of environment is, in fact, substantial. That interesting tidbit leads naturally to the next chapter which discusses the continued growth of average IQ through the 20th century and into the 21st.

Chapter 3

(Getting smarter) examines the puzzling relentless upward trend in IQ results, for all populations, over the last 90 years. The so-called Flynn effect is the upward trend in average IQ score in the US from 1947 to 2002, roughly 0.3 points per year for a total of 18 points of increase. Where does it come from? And how can it keep climbing? The answers are fascinating. IQ tests were developed and refined during WW1 to help the Army predict the academic potential of its recruits. The tests were largely successful and led to their wider adoption in subsequent years.

The growth in IQ through the 20th century largely parallels the expansion of, and change in, the schooling received by the American public. It can’t, for example, be attributable to IQ test-taking familiarity since that was largely non-existent before WW2. Nor can it explain the phenomena in the years since WW2 because IQ re-testing only tweaks IQ results by several points. Similarly, nutritional deficiencies substantial enough to seriously impede IQ largely disappeared in the US after WW2. So we can have some confidence that the growth in IQ over the last 60 years has some very real ties to education.

So each generation is “smarter” than the previous. And noticeably moreso than their grandparents. Is there something about schooling that makes you smarter? Strangely enough, we can say with some certainty that time away from school — summer vacation — seems to make you “dumber.” Student growth in IQ (and academic skills) stagnates or even falls backwards during summers off. Nisbett works his way through the literature on the impact of schooling (number of days per years, number of years total, variations between schooling hours in different countries) and largely concludes that more schooling increases IQ … that one year of school has twice as much impact on IQ as one year of additional biological age. Dropouts, for example, have anywhere between a 13 and 18 reduction in average IQ. In cases where schooling was arbitrarily cut off from children during the 20th century (examples include WW2 and periods of civil rights controversy in the US) children had noticeable reductions in average IQ … as much as 2 points per year of schooling missed.

Most interestingly, even a few months of Western-style schooling can have a major impact on IQ for both younger and older children in places such as Africa where neither IQ testing nor formal education have been available. Clearly IQ is measuring something acquired by schooling and reinforced by physical and social maturation.

What does this mean at a practical level? Say a post-WW2 grand-parent had an average IQ (100). They would find a modern four-year college curriculum very tough. Their grandchild with a 118 IQ however would be considered well-equipped for a profession and for the extensive post-secondary and graduate education involved.

A side-issue associated with IQ has always been “culture-relevance.” Are IQ tests inherently biased to particular cultures? The results of recent testing which correlates very modest Western education with big jumps in IQ test results in developing nations suggests that even the IQ tests which proclaim themselves most independent of any particular cultural content (names, dates, grammar, etc.) such as the Raven Progressive Matrices are actually measuring something enhanced by the content and nature of modern education. What is it?

“[W]e have every reason to believe that the culture is producing superior executive-control functions than were found for earlier eras, and that these altered executive functions are improving performance on fluid-intelligence tasks — certainly for Raven matrices and probably for other fluid-intelligence tasks such as those in the WISC performance package.” p. 50

It turns out that the shift in education over the last century (and even videogame entertainment in the last two decades) has been enhancing ability in particular kinds of categorization, organization, modelling, and analysis.

“… [I]t does mean that we can think analytically in ways that help us to understand and generate metaphors and similes and that we have gained in our ability to categorize objects and events in ways that are relevant to scientific classifications. And these changes are of real significance.” p.52

While there has been no improvement in scores related to static information or simpler arithmetic ability … there has been a major change in the more advanced kinds of mathematical skills and the capacities which support scientific reasoning and logical organization. Nisbett notes in passing as a case example that geometry was an advanced subject for schools in 1900 and calculus was left largely to colleges. In 2000, calculus is now widely taught in high school and sometimes creeps down into junior high. And while the Flynn effect appears to have levelled off in places like Scandanavia, IQ averages are surging in the developing world as exposure to particular kinds of education, and more years of education, are becoming more widely available.

Chapter 4

(Improving Schools) looks at school performance and the quality of educational social science research that evaluates school performance. Angst over US performance on the “league tables” of the world’s educational systems is perennial. Just like health care, one can find pockets of excellence and pockets of abject failure. Nisbett notes that US students taking advanced placement (AP) calculus and physics (1% and 5% of American students respectively) do about as well as the top 10-20% of students in other nations.

Is it a matter of money? Whether the students are rich or poor, adding more money to the current systems does not appear to be an influential factor. Where civil rights litigation has mandated the investment of many millions of dollars in schools, gyms, pools and equipment (e.g. Kansas city) it has had no impact on school performance. While Nisbett does support spending more than what is spent now, it must be spent in particular ways.

Voucher systems and charter schools do not appear to be a panacea either. There is the problem of self-selection … parents who take/use vouchers or who jump through the hurdles to put their children in charter schools are likely superior parents in the first place. Parents who don’t seek out such educational advantages may be more influential (in a negative sense) than any specific educational system. Some research claims a 1/3 reduction in the black/white IQ gap in such schools but the underlying ability to properly control sample groups opens the results to serious question.

When lotteries are used to control access to charter schools, a .10 SD difference in IQ distribution (very small) is identified. Nisbett says that these schools may be good, but there is no good evidence to prove it. The research does suggest that charter schools have minimal impact on student performance in first few years of operation and are much less positive for students who starting in the charter environment at an older age.

If not money, then, what can positively influence IQ and academic performance? The research on class size is conflicting, though it does seem to help more for poor and minority students to have smaller classes. The training of teachers (certificates or graduate degrees) has no impact on teacher quality … though stronger evidence suggests that first year teachers can have a negative effect on class success. There is plenty of solid anecdotal evidence for the powerful influence of individual teachers on many hundreds of their students … but such “statistical outliers” are an impossible way to renovate an educational system. It does appear that excellent first-grade (even kindergarten) teachers have an outsized impact on eventual student success.

All this discussion takes place in the debate minefield of teacher compensation. How to identify, train, and reward good teaching is “very poorly handled.” The tales of “effective schools” are rarely more than anecdotal and it’s clear that Nisbett (coming from social and cognitive psychology) is a bit scandalized by the state of the quality in educational research which “rarely rises to the level of being scientifically acceptable.”

[…] schools with better outcomes have better principals with better strategies and teachers who are more committed to seeing that their students flourish.”p.67

” Without knowing *that* a treatment is effective, there can be no way of knowing *how* it is effective.”p.68

Nisbett turns his attention from the issues of educational funding and technique to look at “whole school interventions” but finds that research into their effectiveness is similarly poor in design, under-sized in scale, or simply not extended for a long enough period. The research out of instructional design offers a bit more hope. Computer usage for instruction in math and reading, or for the use of mentoring, appears to make a significant positive impact. A structured mentor/student approach can similarly be beneficial. Nisbett does recommend the US Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse as a first stop for parents and teachers seeking educational methods that have some solid (or relatively solid!) research behind them.

There are interesting hints of what curriculum enhancement might offer if a focus was made directly on logical thinking and problem solving. Many years back I recall hearing that Edward de Bono (the originator of the term “lateral thinking”) had successfully convinced the Venezuelan government to introduce one of his courses into the national school system. Nisbett notes the research of Richard Herrnstein in the same country, looking at teaching seventh-graders the basics of problem solving. The results clearly showed that general problem-solving skills can be directly taught and practical abilities substantially enhanced. A change of government, apparently, spelled the end to the program and research. And in light of recent news from the region, we’re unlikely to see Venezuelan petro-dollars directed to teaching thinking skills in the classrooms of that nation any time soon.

Nisbett wraps the chapter with a summary of the great deal that we do know about effective instruction and the little we know about good-to-great teachers. The absence of solid evidence on entire school systems that work (in all SES environments) is something that clearly bothers him.

Chapter 5

(Social class and cognitive culture) returns to a discussion of socio-economic status and its impact on IQ. The author leads with some sociological definitions of the poor (unemployed, on welfare, non-skilled), the working class, middle class, and upper-middle class. He first reviews the specific environmental issues that affect IQ and IQ development for children in poverty: low birth weight, poor overall health, lack of breast-feeding, inadequate or non-existent medical care, local pollution, and asthma are just a few of the highlights. In terms of the social environments for kids, poor families tend to move more often and children have increased behavioural problems. Parenting is usually described as “punitive/stressful.” Disrupted neurological development in early childhood can’t help but have downstream impact. There’s some suggestion that the prefrontal cortex has a role in “fluid intelligence” of the kind directly measured by IQ tests. I don’t think it will come as news that kids from poor households have lower average IQ and academic achievement.

Nisbett notes that US income disparity is usually matched with a skill disparity and that “gap” sets the tone for the adult stress levels and cognitive/social focus of the family. The author implies that this is something that can and should be urgently addressed. To chip in my own two cents, I think it’s worth pointing out that American social disparities are inevitably inflated by a scale of immigration (legit or otherwise) that inadvertently re-supplies the unskilled labour pool. Tens of millions of unskilled immigrants have moved their families into the middle class during the 19th and 20th centuries. It hardly seems fair to expect the US, alone among industrialized nations, to approach the levels of income equity shown in the rest of the G7 when only it is expanding its population.

It will be pretty hard to shrink the relative size of the low SES group in the US without some major economic and political adjustments. The industrialized populations in the EU and Japan (now well under zero population growth), have low to nil immigration and therefore less income disparity. They manage only about 75% of the per-capita annual GDP of the US (see cb review of pertinent data). The capacities of those nations to actually accept large numbers of immigrants is therefore much more constrained. “Our jobs would be more equitable … if we created any” doesn’t seem like much of a boast.

The point the author makes, that household income can directly influence childhood development, is a solid one. I’m not sure “elevating IQ” has any more traction on the Right as a rationale for income redistribution than “merit pay for teachers” has on the Left. The disparity between reading and math skills for the top 25% of SES versus the bottom 25% mimics the difference between the developed world and developing countries. In other words, big.

“In a word, if we want the poor to be smarter, we need to find ways to make them richer.” p. 85

What is the role of the “cognitive culture” of a family or community on childhood development of IQ? The differences in behaviour between families in different SES groups is one of the most interesting parts of this book. Children in the families of professionals & high-level managers are cultivated to have questioning, analytic minds. Parents in lower SES families feel successful if they raise obedient children with good behaviour. Professional parents talk more to their kids and include them in adult conversations with vocabulary they may not immediately understand. Researchers have actually monitored parental behaviour across the spectrum of SES groups in great detail. Professional families speak an average of 2,000 words per hour to a child versus an average of 1300 words per hour in working class families. By age 3, that’s a difference of 30 million words versus 20 million. Kids raised in professional families will have 50% more vocabulary words than working class kids by that time. The tone and nature of parent-kid interactions differ substantially. The ratio of encouragement-to-reprimand is 6:1 in professional families versus 2:1 in working families. And it’s encouragement, as opposed to flattery or abuse, that seems to propel learning and curiosity and, in turn, enhance IQ.

Middle-class parenting encourages an analysis of the world, emphasizes reading more to children, provides more child-friendly books in the house, makes particular kinds of intellectual requests of children. Beyond simply the analysis of what (identifying the object), there are the why? questions, placing the object in a dynamic environment. Middle-class kids are frequently asked to evaluate and compare, often in the context of reading.

For the working class, raising a successful children is about socialization for factory and office. There is an emphasis on paying attention in a timely fashion and following direct commands. There’s no request to interpret detailed instructions which must be then tweaked for the practical world. Recipes are more rarely used for food preparation. As a result, the “translation tasks” that middle-class kids are inundated with are simply absent in many working class environments. It’s not hard to imagine how kids then respond to such tasks in the first few years of school. They’re confused (1) by what they are being asked to do, and (2) why an adult in authority would be asking them to do it in the first place. As a result, working class kids tend to drop in academic skill during summer vacations while middle-class kids merely stagnate in their skill levels.

Interestingly enough, these different cognitive skills in home life actually persist, according to the research, beyond an immediate improvement in family economic circumstance. Parents who’ve lifted themselves from the working class in young adulthood nonetheless tend to raise their middle-class kids in a working class manner. Apparently it takes a generation or so to integrate the educational and occupational obsessions of the middle class into home life.

Chapter 6

(IQ in Black/White)

Having set the stage for the contrast between midde-class and working class realities for childhood development styles of child-rearing, Nisbett returns to the issue of race and IQ, providing a specialist section in Appendix B for readers with the background and motivation to address the scientific literature directly. How does black America fare in a world that rewards particular kinds of intellectual skills with money?

In preamble, the author notes that the Moors and Jews of Spain, and the Romans and Greeks of the classical era, had a very low opinion of the intellectual capacities of the northern Europeans. So prejudices about what different races are capable of is nothing new. Until 600 years ago, there was little to suggest that Europe would be generating anything new or useful. Crosby’s Measure of Reality reviewed a few years back in chicagoboyz opens with the contrast at the time between the Islamic and European worlds. Expectations about particular races and groups shift back and forth through history as wealth and technology change hands. To a measurable degree, however, black Americans have internalized recent expectations about their genetic capacity and Nisbett reviews the literature from social psychology on the impact of testing IQ in black populations under conditions where there is a “stereotype threat.” The publication of The Bell Curve in the mid-90s kicked off a fierce, and ultimately too brief, public discussion of race and IQ. Despite the fact that average black IQ in America now matches (courtesy of the Flynn effect) the average IQ of white America in 1950, there is still a widely-held assumption that it is genetic capacity that will hold back blacks.

Turning to physiology, Nisbett notes briefly that attributes like brain size are poor proxies for intellectual capacity. While men and women notably different in brain size they share the same average IQ. They do not, it should be noted, shared the same distribution of IQ across the lower and higher ranges. Average human brain size has actually been shrinking since the first appearance of homo sapiens sapiens some 200,000 years ago. So brain size offers no particular value, at this point, to the discussion of IQ.

What about correlations between specific genetic makeup and IQ? If African genes have any role, or place any limitation, on intellectual capacity, black Americans provide the ideal study group to provide it … since they have widely differing ratios of European genes in their genetic makeup. But when studies of detailed genetic makeup are matched with IQ, there are no correlations between the extent of European ancestry and IQ. Other studies with mixed-race kids in post-WW2 Germany show similar results.

As mentioned, with the advent of additional schooling and the impact of education and occupational opportunity, average black IQ is now superior to that of average white IQ in 1950. Black IQ has seen rapid growth, both in a drop in the absolute size of the black/white IQ gap and in the relative improvement of black IQ toward the moving target provided by the Flynn effect. As Nisbett notes, these reductions are non-trivial, especially amongst the higher ranges of IQ. A 15 point gap in average IQ of one group over another would lead one to expect an 18:1 ratio of individuals with an IQ over 130. And an IQ of 130 is the rough benchmark for expectations of stellar achievement in the professions. A 10 point gap in relative average IQ between two groups however reduces the expected ratio of individuals with an IQ over 130 to 6:1. These changes in ratio translate into tremendous jumps in representation in higher SES groups.

Every bit of “catching up” in IQ has massive implications for academic achievement and occupational accomplishment. The “multiplier effect” is at work again.

Nesbitt, making the case for the broader role of environment in the determination of IQ, notes that black America still has many environmental barriers to accomplishment: lower SES (and all that entails, discussed above), redlining in housing, single-parent families, etc. etc. He identifies two trends: one good, one bad. The growth of middle-class black America has been substantial and it’s shown up in the rocketing average IQ figures for that segment of America. But there is also a lower class black America and the catastrophic changes occurring in the black families outlined in the Moynihan Report have become exacerbated. Cultural attitudes by young, black males has opened up a difference in average IQ between black males and black females that is unseen in white populations.

The discrimination against blacks, per se, in northern cities is really a 20th century phenomena, according to Nisbett. Indeed, the 19th century Irish and Appalachians were considered less desirable workers and neighbours than “free blacks.” The author turns to much of Thomas Sowell’s research to fill in the demographic and cultural changes in rural and urban America that shifted attitude to skin colour in the last 100 years. Even today, the attitude in American cities to West Indians with African backgrounds is driven by a reputation for incredible hard work and family durability. As Nisbett notes, ironically a lilting Caribbean accent (despite the colour of one’s skin) can be a passport to opportunity in America. A negative reputation can be equally devastating.

In a discussion sure to raise eyebrows, if not hackles, Nisbett looks at the sociological information on the role of home life in black America on IQ scores.

“On top of all the demographic disadvantages of American blacks as a whole, many also socialize their children in ways that are less likely to encourage high IQ scores and high academic achievement than do whites of comparable social and economic circumstances.” p. 111

Recalling the statistics discussed earlier where professionals averaged 2,000 words per hour with their infant children, and working class families averaged 1,300 words per hour with their children, black Americans on welfare averaged 600 words per hour with their very young children. Extrapolating as before, that means that a three year old from the respective SES groups will have had 30, 20, or 10 million words directly at them. With vastly reduced direct adult interaction, a dramatically narrowed list of vocabulary, few if any books (and none suitable for children), and a dramatically reduced set of parental demands to identify objects or create verbal or written responses … school age analogies and extrapolation are largely impossible for kids from poor families just starting school. Requests from a kindergarten or first-grade teacher are a complete mystery. Without familiarity at home to structured story-telling, and with limited opportunities to gain skills in categorization, an child’s extrapolation from a stylized school-time story to real objects in the world is incredibly difficult.

Studies following up specific communities after a 20 year interval suggest that for some African-American families the “cognitive style” and parenting skills have gotten even worse. For black families on welfare, the encouragement-reprimand ratio for conversations with their children is 1:2, in comparison to professional families (6:1) and working class (2:1). As mentioned above, the black middle class is making significant gains in average IQ scores but it still contains an adolescent male subculture that considers many of the academic skills needed to boost IQ scores as “acting white.” Athletic ability or an entertainment career is seen as the only acceptable path forward. This is creating a divergence in average IQ scores (and subsequent academic attainment) between black females and black males … destabilizing black families even further.

The story of IQ in black and white has optimistic and discouraging elements.

Chapter 7

(Mind the Gap) looks at educational initiatives to reduce the IQ distinctions between different groups in America. In 2002, the No Child Left Behind Act mandated the elimination of a vast array of educational gaps (between races, ethnic groups and social classes) by 2014. Nisbett is singularly unimpressed.

“Intellectual capital is the result of stimulation and support for exploration and achievement in the home, the neighbourhood, and the schools. To think that this can be changed by mandate — operating only through the schools — is preposterous.” p.119

As Nisbett outlined earlier, while the gap between the races in average IQ scores is closing rapidly as access to education and occupational opportunities continue, the gaps in average IQ scores between the social classes are persistent. There is a built-in bias for high SES groups, because they not only have a marginal (and understandable) higher average IQ to begin with but the environment in which they raise their children is optimized for the development of particular kinds of skills. The fact that the best research available suggests a 12 – 18 point IQ advantage to being raised in a higher SES group than the lowest SES group simply confirms the current situation. It does not place an inherent limit, however, on the the potential increase possible to all kids, across the socioeconomic status spectrum. As described in earlier chapters, the educational system is still very poor at designing researcht that will identify and put into practice the methods and resources that will work. We do know that children experience a halt or drop-off in their intellectual capacity during summer vacation. What of the time before they even get to school?

Plenty of evidence suggests that early childhood education programs (the poster child is Headstart) do not get great results and are questionable value for money. For one thing, such programs cannot be sporadic or occasional. They must be sustained (as the vacation drop-off phenomena suggests). Yet many of these early childhood initiatives have better accomplishment outcomes than their gains or sustainment in IQ scores. In other words, subsequent evaluations of student participants may see initial IQ gains fade, but a pattern of improved social and occupational achievement may continue later in life.

This is all rather mysterious at the moment. We know that the abilities reflected in high IQ scores open up opportunities for academic achievement and occupational accomplishment. IQ acts as both enabler and multiplier for many positive things in a person’s life. How particular programs could temporarily increase IQ growth and yet maintain longer-term impacts on practical achievement seems like a significant piece of information. One that researchers would want to examine with carefully designed experiments.

Unfortunately, Nisbett’s review of the scientific literature on pre-school and primary school education suggests that “bad research” and “no research” are the only kinds of research in great supply. He looks at isolated examples of great results from temporary programs from decades past (e.g. the Abecedarian program of the 70s and the Perry Preschool program of the 60s). Again the pattern shows that comprehensive, year-round programs that acknowledge and support the child’s home life can make an impressive difference in IQ scores … and that those scores may fall back when the programs end but the differences in lifetime achievement can still remain significant. Black and Hispanic children seem to benefit the most from the pre-school programs, as would be predicted if they are most lacking in family environments which inadvertently reinforce the acceleration of fluid intelligence in specific areas.

The results of school-age interventions suffer, as mentioned above, from the problem of self-selection. Parents who persist in finding the best education for their children may well outweigh all the other influences that good educational methodology could provide. In some socioeconomic settings, having parents at all is a major childhood advantage. Nisbett finds questionable research methodology rampant in evaluations of the many school-age programs that are available. He looks at Project SEED, a Heritage Foundation program, and the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP). Yet again we see extraordinary individuals such as math teacher Jaime Escalante (of Stand and Deliver fame) can make incredible strides in educating kids from lower SES backgrounds. But extraordinary individuals and fortuitous combinations of principals and school budgets make such stories unique and always ephemeral.

Nisbett also reviews the inexpensive interventions tested by social psychologists to support improved learning. Simply telling students that IQ is not a fixed value can encouragement improvement. Or asking them to map out their future, before undertaking a course of study. Or reassuring minority students, through experimental means, that people from all races and backgrounds share worries about academic ability and social acceptability when they enter high school or college. It’s clear, by implication, that there are many small and cheap ways that they educational system could remove minor barriers to educational success, even if the big barriers remain.

Interestingly enough, college seems to have fewer distinctions in attitudes between the races than high schools. Nisbett hypothesizes that the quality of the education is more even across institutions, that there is less peer pressure to not “act white” and less intentional “effort reduction.”

The author wraps up the chapter with a summary of programs with clear benefits for minority kids — SEEDS (math) and Reading Recovery (reading). The KIPP program, with young teachers working at reduced rates for several years, also appears successful. But are these benefits worth their costs? What are the social benefits of each year a child has an solid education versus the social costs when they don’t? Can such programs still be run effectively when regular union rules about teacher behaviour and teach compensation (driven by seniority and certificates) are enforced?

It certainly appears that we know how to improve minority education (at school and at home). The paucity of any research conducted in the last few decades, however, suggests neither the money nor the the political will exists to intrude on low-income homes to directly change parenting practices that inhibit IQ scores (and associated later achievement).

James,

Thanks for the excellent post!

I’m going to review on certain parts of Nisbett’s chapters, as reflected in your post. Much of the writing seems solid, so I will save my comments for those parts I disagree with.

Second post seems solid. Some claims mentioned by first post are more questionable. Not sure if I will just copy and paste from this email to comment, or revise further. We’ll see how opinionated I get ;-)

1 & 2. This is mentioned late in the second post, but f there are two sources of variation, it’s obvious that the effect of one increases as the variation in the other is reduced. So obviously, the more you vary nurture, the less nature seems to matter, and vice versa.

3 & 7. Summer vacation only makes dumb kids dumber. It makes smart kids smarter.

I mentioned this in passing earlier.

http://www.tdaxp.com/archive/2009/03/10/obama-on-education-2.html

SES is deeply, deeply unfair. Solutions which we may devise to help the slowest will hurt the swiftest.

4. Saying the top 20% of Americans are on part with the top 20% of international students doesn’t do much good for the author’s goal of equality, fi the other 80% are dangerously behind.

5. There may be something to parenting, but I would like to know why whites do best w/ authoritative parenting styles, and blacks and asians seem to do best w/ authoritarian parenting styles. I can’t make anything out of this repeated finding in parenting research. It seems arbitrary.

6. This sort of close-our-eyes nonsense is everywhere in the debate on race, mostly on the side of merrily ignorant liberals.

“What about correlations between specific genetic makeup and IQ? If African genes have any role, or place any limitation, on intellectual capacity, black Americans provide the ideal study group to provide it ”¦ since they have widely differing ratios of European genes in their genetic makeup. But when studies of detailed genetic makeup are matched with IQ, there are no correlations between the extent of European ancestry and IQ. Other studies with mixed-race kids in post-WW2 Germany show similar results.”

The first part of this claim strikes me as absurd, even assuming that the genetic contribution of IQ is always zero. Imagine you have two populations which differ in IQ and SES entirely for cultural reasons. Now imagine some cross-breeding between them. As like breeds with like, we should expect that lower-than-average IQ/SES members of the higher-performing population would mate with higher-than-average IQ/SES members of the lower-performing population. Sure enough, that’s what we see with white-black (“African-American”) mixing. There’s a whole literature on whether this can explained as high-performing blacks ‘trading’ objective spouse quality in exchange for social access. So my impression is the author’s comments here are making facts up.

The interpretation WW2 Germany study is actually contridcted by another part of the synopsis of the book. The Army used IQ testing to sort recruits. In general, a soldier with a bastard in Germany was (a) smart enough to get in the infantry and (b) dumb enough to be in the infantry (alternative: smart enough to blow-up a German and dumb enough to knock-up a German). Unless the author is arguing that the WW2-era army engaged in massive affirmative action, there’s no reason to expect an IQ gap between black infantry and white infantry.

I mentioned this two years ago

http://www.tdaxp.com/archive/2007/12/04/genetic-and-environmental-causes-of-human-diversity.html

Also, the comments on the Flynn Effect are deceptive, as you are trying to compare two scales that are differently normalized. Imagine weighing yourself and your wife first on a scale on the Moon, and then one on Earth. “Look, honey,” you say, “you are already as massive as I was on the Moon!” If you do that, you might be Richard Nisbett!

1. There can be no question that some people sre duller than others and some are sharper. This difference might have something to do with intelligence. I doubt that it has anything to do with IQ.

2. IQ was invented by teachers to explain why some teachers are better than other teachers. Better teachers are better because their students have high IQs. Bad teachers are bad because their students have low IQs. And the teacher have developed tests that prove that teaching ability has nothing to do with how much the student learns, provided the teacher is a union member.

Great post. Nisbett’s research is extremely well-regarded and solid, even if he panders to liberals with his definitions of equality (What discipline, outside of economics, DOESN’T do so at the PhD level?).

My (soon-to-be) wife has very similar interests in cultural and cognitive psychology, especially regarding intelligence and the east asian/western divide. If you want to read research of equal quality (without the prestigious name) I’m sure she would have have a dozen recommendations.

Off the top of my head:

On Intelligence: The Mindset by Carol Dweck (Stanford). Comes from a ‘culturally blind’ lineage so east/west divides are ignored. Excellent insight into motivation and behavior as it related to cognitive psychology and real-life achievements.

On East/West Cultural Divide: Heejung Kim (Stanford PhD, currently at UCSB). This woman is absolutely prolific in the field. She is making enormous strides in the body of cultural psychology research.

Happy readings.