Chua, Amy, World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability , Doubleday (2003) 340 pp.

, Doubleday (2003) 340 pp.

In a post earlier this year, Jim Bennett outlined both his concerns and his appreciation for Amy Chua’s book “World on Fire.”

Unlike Jim, I was less convinced that she was offering a “one size fits all” model but very much inspired by the utility of her model for understanding the relationship of the world to the United States and the Anglosphere. The US, and its occasional allies, are locked in a passionate love-hate relationship with the rest of the world — a discussion fought now on television that often appears deranged or infantile yet is driven by very real concerns and anxieties. There’s hypocrisy and cant aplenty on both sides of the argument as far as the eye can see. And it is the “do as I say, not as I do” conundrums facing the Anglosphere that will drive new and focused solutions — new legal structures, new ethical propositions, new responses to weapons of mass destruction and hyper-destructive individuals, new balances between individual and social rights, new clarity and, one assumes, a newly-minted sense of self-preservation.

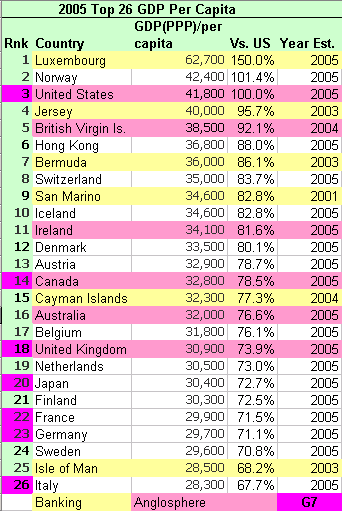

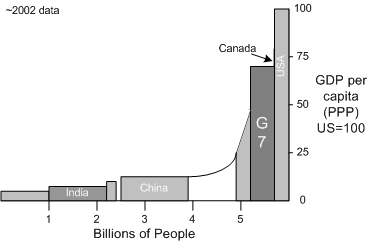

Much of the reading I’ve been doing over the last year has focused on national productivity figures (cf. Lewis’s The Power of Productivity) and on the EU’s response to the increasing GDP per capita gap between it and the US (The 2000 Lisbon Agenda). To summarize: the United States (with 300 million people) has roughly 30% greater GDP per capita (purchasing price parity) than all other nations over 10 million in size. Canada (at roughly 78% of the US standard and 30 million people) is the only exception. US GDP percentage growth also leads its large industrialized competitors. My reading focus has been on the solutions offered by serious people around the world to close the gap or find a way to accommodate the gap within a successful sustainable social model. At the same time, I’ve been watching the figures, and discussion, on higher education and the “scientific wealth of nations.” In many ways, however, the responses and strategies put forward to catching up with the US, by both the industrialized and industrializing world, have been eerily parallel to those documented in the past by Chua for nations who have struggled to cope with free markets and democracy over the last forty years. There’s a lot more finger-pointing and bad-mouthing than concrete progress.

To quote Chua (p.6):

This book is about a phenomenon – pervasive outside the West yet rarely acknowledged, indeed often viewed as taboo – that turns free market democracy into an engine of ethnic conflagration. The phenomenon I refer to is that of market-dominant minorities: ethnic minorities who, for widely varying reasons, tend under market conditions to dominate economically, often to a startling extent, the “indigenous” majorities around them.

Read more