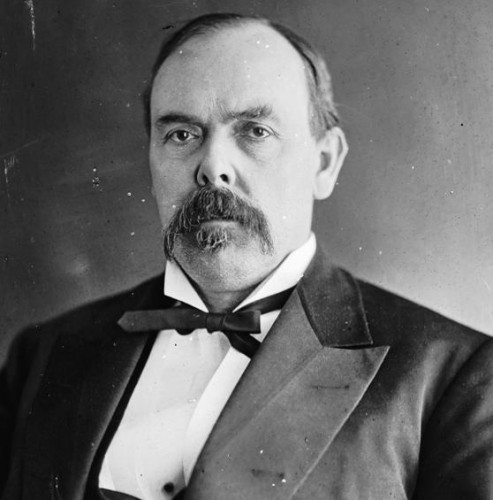

I mentioned Oliver P. Morton, the Governor of Indiana during the Civil War, in this post.

The statue in front of the Indiana state house has a plaque which says he shall “ever to be known in history as”¨ The Great War Governor.” When the Union veterans who built the state house and put up the statue were alive, I am sure they believed the heroic deeds of the war would “ever be known … .”

But one of the lessons of history is the fleetingness of fame. The things that move and inspire one generation are rejected by the next, or simply forgotten. This is especially true in America, where we are a forward looking people and typically not terribly concerned about what happened in the past. Henry Ford spoke for America when he said history is more or less bunk.

This short article from the Indiana Historical Bureau, entitled OLIVER P. MORTON AND CIVIL WAR POLITICS IN INDIANA is worth reading.

At first, as is often the case, the war generated enthusiasm and unity.

Hoosier support for the Union surpassed all expectations. When the war began with the shots fired at Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. Governor Morton responded by telegram that same day, tendering 10,000 Indiana soldiers to enforce the laws of the United States, four thousand more than he had offered the national government back in January. The War Department informed Morton that Indiana should provide about 4,600 men, in six regiments. In keeping with his Union Party ideal, the governor appointed Lew Wallace, a Democrat and military veteran who had served in the U.S.-Mexican War, to the post of adjutant general and tasked him with mustering and preparing the troops for service. Within days, Wallace transformed the state fairgrounds at Indianapolis into “Camp Morton,” and began the work of training the volunteers. Meanwhile, the Indiana General Assembly passed resolutions supporting the war and voted for laws giving the governor the authority to borrow money and spend it to purchase arms and supplies for the troops. The legislature also expanded the governor’s authority over the state militia. Democrats voted along with the Republican majority to mobilize the state for war. No wonder the Indianapolis Daily Journal, Indiana’s leading Republican newspaper, joyously argued that, “We are no longer Republicans or Democrats,” but that “in this hour of our country’s trial, we know no party, but that which upholds the flag of our country.”

[T]he governor proved an effective administrator. Under his leadership, troops were recruited, enlisted, trained, equipped, supplied, and made ready for service in the U.S. Army. To be sure, it wasn’t easy. Finding enough guns, uniforms, and supplies of food required long hours and lots of ingenuity. Morton lived up to the job, visiting Washington to obtain arms, scouring the state for weapons stored in local arsenals, and sending Owen on purchasing trips. His efforts proved so effective that he became the most famous of many politicians called “The Soldiers’ Friend.”

Political opposition arose and became organized as the war dragged on, and Lincoln and Morton cracked down — up to and over the limits of their Constitutional authority.

The Democratic convention in January 1862 marked the end of political unity. There, the growing dissent among Democrats erupted into action; the party adopted a platform that promised support for the war and the Union, but also criticized the Republicans for trampling on the Constitution and destroying liberty. The arrest of Democratic leaders and newspaper editors critical of the Lincoln administration lent credence to their arguments, as did the federal government’s suspension of habeas corpus later in 1862.

The growing power of government also divided Hoosiers, as plans for conscription began to be implemented. Governor Morton and other leaders tried to delay the draft, but it became clear that it would soon be a reality, and many Democrats denounced it as a further example of tyranny and another loss of liberty. Union prospects looked bleak as the war became so unpopular and costly that the government had to turn to conscription to enlist enough soldiers to fight it.

Indiana was strongly for the Union, but only a minority were abolitionists. The Emancipation Proclamation was not widely celebrated in the Hoosier state.

In the North, the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation set off a political firestorm. While abolitionists delighted in Lincoln’s move, most Democrats saw it as a confirmation of their fears about the Republican agenda. Their worries that the Republicans wanted to implement a nationalist expansion of government power now combined with their fears of the abolitionists, who they argued wanted not only to end slavery but destroy American values and tradition. They argued that emancipation would bring thousands of unwanted black immigrants to states like Indiana. Many Northerners, including many in Indiana, balked at the very idea of emancipation and expressed their outrage that the War for Union had now become a war about slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation undercut Morton’s careful cultivation of a working political alliance with pro-Union Democrats.

The slavery issue now boosted Democratic political fortunes again, and they swept the state elections in October 1862, winning seven of the eleven congressional seats and a large majority in the state legislature. The stage was set for a Democratic showdown with Governor Morton.

When the Democrats took control of the legislature in January 1863, the official Emancipation Proclamation had just taken effect. Its widespread unpopularity gave the Democrats confidence in their designs to challenge the governor and take power from him.

The Democrats had their majority, but Morton and his allies used both legal and illegal methods to thwart their efforts to push back against Lincoln, Morton and the Republican prosecution of what had become a war against slavery.

Democrats passed resolutions criticizing Morton and Lincoln and denounced their Republican enemies as tyrants and dictators in long, rousing speeches. They also called for investigations of Republican abuses of power and the infringement of civil liberties, including the arrest of those who had criticized the administration. Peace Democrats seized the opportunity presented by the unpopularity of the Emancipation Proclamation to introduce resolutions calling for an armistice and a negotiated peace with the South. The Democratic majority challenged Morton’s power directly by introducing a new militia bill which severely limited the governor’s authority and established a committee of state officers to share control of the militia with him. Time after time, the Republicans bolted from the session to deny the majority a quorum and prevent passage of Democratic measures aimed at the Governor.

When this parliamentary maneuvering was running out of steam, Morton simply took over the state and ran Indiana by totally extra-Constitutional methods.

When the Republicans bolted to stop the militia bill, the session ended. Democrats confidently prepared for stronger measures when the governor called for a special session, which they were sure he must do because they had not passed an appropriations bill and, without a budget, the state government would come screeching to a halt. But Morton surprised them by refusing to call the legislature back into session and instead began a period of “One Man Rule.” He borrowed money from New York bankers and the counties controlled by Republican commissioners. He obtained funds from the War Department and took additional money designated for the state arsenal. Morton kept all of this money in a large safe in his office and disbursed it through an assistant he named to head the “Bureau of Finance.” Ignoring the state Constitution and the illegality of his actions, the governor effectively ran the state without the legislature until after the next election; he finally reconvened the Indiana General Assembly in January 1865.

Morton hung on, despite the increasing unpopularity of his unlawful measures, by vilifying his opponents as traitors and by claiming the existence of conspiracies against him and the Union cause.

Orderly politics and law abiding government returned with the Confederate surrender.

That is often what happens in Anglosphere countries, over the centuries. The people are willing to tolerate extraordinary executive power and discretion when serious military threats exist, but to demand a return to the rule of law when the danger has passed.

Morton was bigger than life, a physically big man, an outsized political operator, and ruthless in the service of the Union cause.

He made Indiana, a state which was deeply divided in its support for the war, into one of the great sources of manpower for the Union war effort.

Morton had a stroke immediately after the war, but went on to serve ten years in the U.S. Senate.

It is interesting to speculate about what you would do, sitting behind the governor’s desk, not knowing how it would all turn out.

Were his actions wrong?

Was his lawbreaking excused by the severity of the emergency?

Was preserving the Union worth the price?

Would the war have been worth it if the Union had been preserved but with slavery still ongoing in some form? We now recoil from that idea, but most of the people who actually fought, bled and died in the Union cause believe that. It is hard for us to imagine now.

In the eyes of his fellow citizens, whatever we may think now from the comfort of our present circumstances, Morton was vindicated by victory.

For those who may want more, here is a two volume biography of Morton, William Dudley Foulke, The Life of Oliver P. Morton: Including His Important Speeches, 2 Volumes (1899).

I especially like this description of the man:

His intellectual processes were clear as daylight. The object to be attained he pursued by the directest road, and crushed all obstacles by sheer force. He disdained the finesse of diplomacy; his weapon was the hammer of Thor. In argument, as in deed, he was not so much persuasive as compelling; he would condense the reasons of his opponents into a few words, and then shatter them at a single stroke. His statement was so strong and his reasons so cogent, that they bore down all resistance.

The winners get the statues.

A similar situation played out in Illinois with the General Assembly dissolved from 1863 to 1865. There were actual rebellious skirmishes in the southern part of the state, but then everything below I-70 has always been more part of the South than the Midwest.

The war really was a serious crisis and these reflections on it put our current state troubles in proper perspective.

Had Sherman not taken Atlanta, Lincoln would almost certainly lost the 1864 election. The alternate history possibilities have been studied including by Winston Churchill in a volume of alternate histories.

Barry “I won” Obama will get the statues.

No chance. Obama got it backward. He started as farce and he is ending as tragedy.