I am reading Churchill: A Study in Failure (1970), by Robert Rhodes James. It is a famous book, which describes Churchill’s career up to 1939. It is an excellent book as of page 132/385. In fact, it is so good, I now want to read other things by this author.

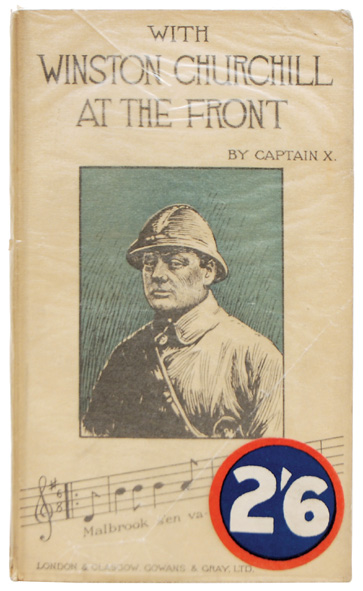

A relatively little-known episode in Churchill’s career was his uniformed service at the front in World War I. Following the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, which was Churchill’s brainchild, he was driven out of the cabinet, where he had been First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill volunteered for active service, and was given the command of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers battalion from January to May, 1916.

Churchill, before being assigned this command toured several sectors of the front, including some visits to the French Army. On one such trip, he was given a French helmet, which he wore throughout his service at the front. Supposedly, this was because he found the French helmet to be a superior design. In fact, Churchill was an actor in a grand drama, and he was always the star. The French helmet, which no one else was wearing, made him unmistakeable in any group and in any photograph.

The helmet was blue.

Rhodes James has a footnote which was intriguing, after mentioning Churchill’s front-line service:

For a delightful account of this period, see With Winston Churchill at the Front by “Captain X” (Captain A.D. Gibb, who was Churchill’s adjutant and subsequently Regius Professor of Law at the University of Glasgow.)

This being the Age of the Internet, I searched for this book and immediately found it full text online as a Word document.

I have been reading it on my phone, in bits and pieces, and it is indeed delightful. This passage I found especially striking:

In the comparatively early days when Churchill was with us it so happened that going over the top was not in the fashion, and so it unfortunately is not my part to chronicle any wild deeds of valour on the part of our redoubtable Colonel with his Scottish dogs of war slipped from the leash. In a quiet time, however, he did contrive to enliven our trench-fighting to a considerable extent, and on more than one occasion seriously to scare the Huns opposite to us.

Going round the line on a beautiful morning about one or two o’clock the Colonel would see perhaps a man or men brought in badly wounded on patrol. This sight brought with it apparently a desire to get some of his own back. I remember well one evening in particular, when we had two men seriously wounded and one killed. Winston’s coming into the dug-out in the front-line where my company commander was sitting, just returned from leave, and recounting his experiences, exciting and highly discreditable, to an enraptured audience. The blue helmet appeared round the door and we heard a voice say: “Come on, war is declared,” and we were bidden all to turn out and superintend the rapid-fire of our half-waking platoons. We found that Winston had arranged for almost all the guns of the Division to support our little alarum, and as soon as the rifle-fire began there was a perfect blaze of artillery behind us and the Hun very soon became alarmed and fired off rockets “of every colour in the summer solstice” s Ramsey put it. Unfortunately he did not confine himself to firing off rockets, but fired off a multitude of whizzbangs and other unpleasant projectiles as well. Just as the enemy field guns began, the Colonel came along our trench and suggested a view over the parapet. As we stood up on the fire-step we felt the wind and swish of several whizzbangs flying past our heads, which, as it always did, horrified me. Then I heard Winston say in a dreamy, far-away voice: “Do you like War?”

The only thing to do was to pretend not to hear him. At that moment I profoundly hated war. But at that and every moment I believe Winston Churchill revelled in it. There was no such thing as fear in him.

He was the only man for the job in 1940. If Britain was actually going to be invaded, and there was going to be fighting in the streets of London, Churchill was the only political leader who would have, at some level, loved the drama, and hoped to leave a blood-soaked legend behind by dying with a rifle in his hand. He said if the Germans invaded, when they were approaching Downing Street, he would have gone out with a rifle and fired at them until he was killed. I am sure he would have done exactly that.

At that moment I profoundly hated war. But at that and every moment I believe Winston Churchill revelled in it. There was no such thing as fear in him.

You don’t hear much about that type these contemporary days, though maybe only because it isn’t fashionable to admire – or even focus on – the kind. And it is a sort of morally neutral quality – like intelligence – that can serve bad as easily as good. I wonder if it’s bred in the bone, or the crib?

The British helmet of WW I always looked absurd to me until I understood what it was really designed to protect against – WW I era shrapnel-shells raining lead balls down into your trench from overhead. I didn’t know that “shrapnel*” in WWI was essentially a giant shotgun shell propelled over the enemy where, when it arced down at the proper trajectory, a fuse would set off a powder-charge at the shell’s base, just strong enough to scoot the balls out of the shell and spread them out. The charge didn’t really accelerate the balls, so they would travel at the same velocity of the shell itself, which by the time it went off might be much less fast than a bullet. Fast enough to cave in your skull, but often not fast enough to penetrate the helmet. The difference between dying and a concussion. I guess the French helmet may have afforded a bit more protection when you weren’t in a trench.

*IIRC, it is named so after a British artillery officer, a Mr. Shrapnel.

RR James is a superior historian and biographer, anything by him worth a read. he was a career Tory MP, so he knew the practical side of politics as well as the scholarly.

My wife first met RRJ at 10:00 one morning. He stank of brandy. It’s remarkable that he managed to write at all.

P.S. About his own life he was a bit of a fantasist – how sound he is as a historian I don’t know.

Churchill highly interesting. Have read a couple accounts of his life. Also wore that hat on visits to the near front lines in WW2

Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.

Winston Churchill

By Luckas. He kept England fighting.

http://www.amazon.com/Five-Days-London-May-1940/dp/0300084668

In Churchill’s autobiographical writings, he tended to downplay his heroics at the front in WWI.

How uncharacteristic of him!