I spoke at the AFEA (The French Association for American Studies, Association Française d’Études Américaines) 2014 Conference on May 23, 2014 at the Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle. The title of the conference was The USA: Models, Counter-Models, The End of Models?

I attended at the invitation of Prof. Jérôme Noirot, of the Ecole Centrale, Lyon. I was initiated due to my coauthorship of America 3.0. My coauthor Jim Bennett was initially invited, but he had a conflict. Fortunately, I was able to attend in his place.

Heartfelt thanks to Prof. Noirot for the opportunity to participate in the conference.

I will also thank here the unnamed individuals whose financial assistance made the trip possible, and my friend who allowed me to stay at his home in Paris.

I participated in a panel entitled “American Politics: What future model for political America: manifestly gridlocked destiny or reinvented union?” A description of Prof. Noirot’s aim for the panel discussion is below.

The evening before the panel I met with Prof. Noirot and we had an excellent conversation. He is unusual in French academics in that he is a classical liberal thinker who is not reflexively opposed to the United States. I found that we were near complete agreement about the world and its problems and the potential solutions. Prof. Noirot emphasized that he wanted the participants to hear a case made for a decentralized approach to economic and political problems, hence his request that I discuss the Tenth Amendment in my presentation.

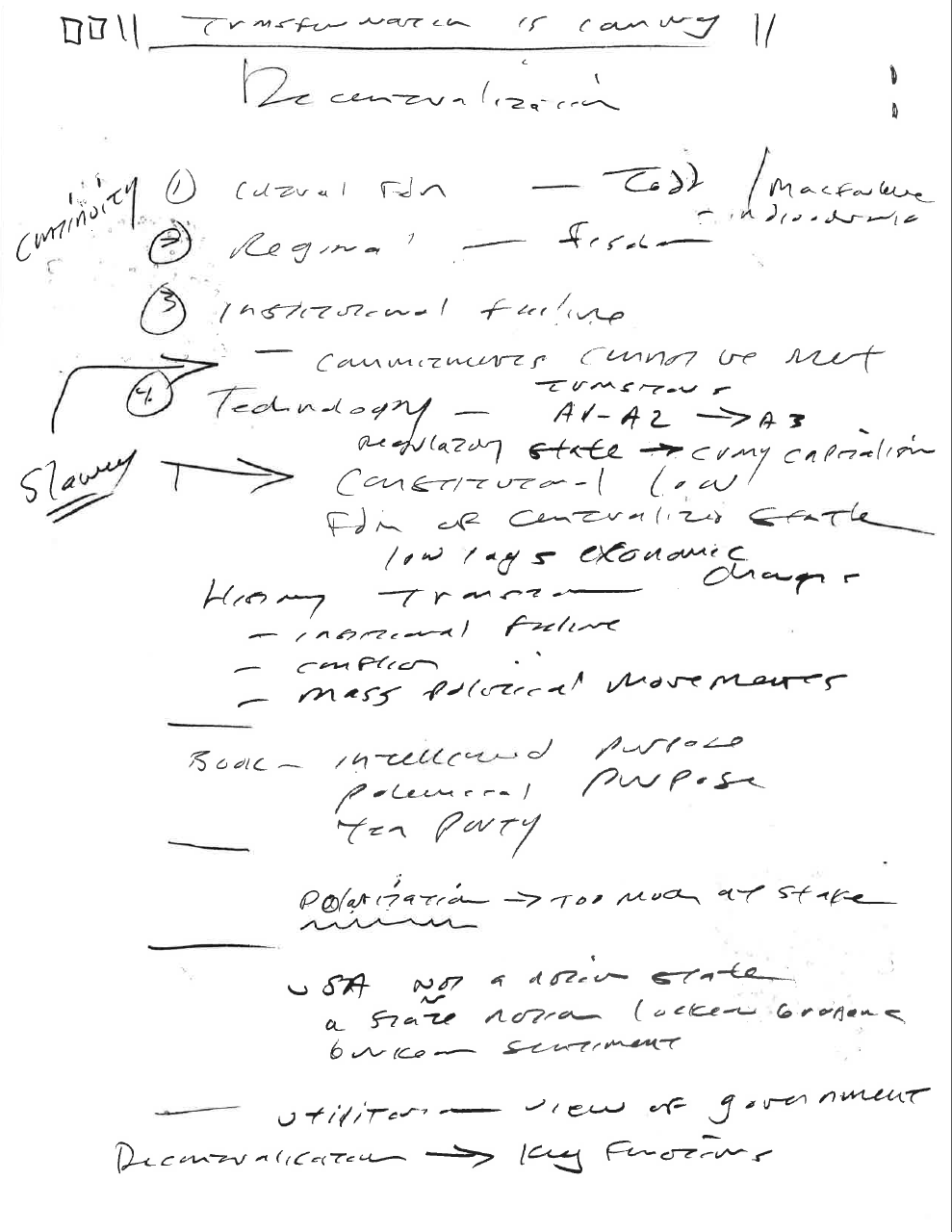

I knew what I was going to say, but I prepared a one page outline, anyway. I always do this just in case I get brain-lock and need to remind myself what I was supposed to be talking about. My outline is below, in my unreadable handwriting, which may provide some amusement.

The next day I travelled on the user-friendly Paris Metro, arrived early, and participated in the meeting. The panel consisted of Prof. Noirot, myself, Ashley Byock of Edgewood College, Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3. Unfortunately, François Vergniollle de Chantal of the Université Paris Diderot did not participate. The panel was conducted in English. Several of the participants were native speakers. Generally the French participants spoke excellent English.

Prof. Noirot spoke first briefly, along the lines of the document appended below.

Then Prof. Byock spoke. Her topic was “The Bonded/Resistant Slave Body and The Emergence of Neoliberalism in the U.S. Context.” Frankly, her approach used terminology which was not familiar to me and I am afraid I could not understand it. For example she used the word “rights” in a way I questioned, and she said she used the word in a literary or metaphorical way. I think like a lawyer. Rights may be metaphorical, but more importantly, they are tangible and enforceable, or they are not really rights. To possess a right means you can invoke the coercive power of the state to compel someone else to do or not do something. Prof. Byock referenced Nat Turner’s rebellion in her presentation, also in a metaphorical way, seeing Turner as a symbol of American discomfort with the image of a strong, Black man. However, I look at Turner more tangibly as a failed guerrilla. I asked her whether she had considered in her analysis that Nat Turner’s revolt failed because he did not have enough guns, and that denying guns to African Americans had been perhaps the most important means of keeping them oppressed. This was, as it happened, not a focus of her analysis. So, that was a bit of a culture clash, but a civil one.

Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy shared with us his research toward his doctorate about the occurrence of certain words in presidential state of the union addresses. The rise and fall of certain terms was demonstrated. What conclusions he will ultimately draw from these findings has yet to be determined.

I spoke last. I summarized the material in America 3.0. I discussed the work of Emmanuel Todd and Alan Macfarlane, which showed the deep cultural roots of American culture. I also mentioned David Hackett Fischer and the regional variety of America, which I believed a European audience would not know about. I then talked about the transition from America 1.0 to America 2.0, and the ongoing crisis as the America 2.0 political and economic structure continues to falter. I mentioned the flimsy Constitutional foundations for the modern centralized state, and how the existing Constitution is well suited to the coming decentralized and networked state and economy. I mentioned the recurring process in America life of the appearance of mass political movements at times of crisis. I explained the Tea Party to them in a way they would not have heard it before, as someone who participated in it, in a small way. I also made clear that America 3.0 had an intellectual purpose, but also had a polemical purpose. The goal of the book is to provide accurate information to inspire political engagement and action. It was not written for academics and we did not seek their approval for what we wrote. I closed by talking about the future prospects of a decentralized America and the ongoing importance of the Tenth Amendment.

I got multiple responses from the group. Generally, no one engaged with any of the substantive points I made. Rather, they seized on points that they apparently perceived as anti-progressive and attempted to shoe horn me into being on the other side of their preexisting opinions even if I had not addressed an issue.

For example, one professor who was an expert on the law relating to voting rights in the USA seemed to think that a less cumbersome federal government would mean that there would be a return to the disenfranchisement of African Americans. Not correct. The size and expense of the existing US Government is going to shrink whether any reform proposal I am making ever happens. Further, in the book we expressly say that protection of civil rights of American citizens is one of the legitimate functions of the Federal government, and in particular the federal courts will continue to enforce the Voting Rights Act and any similar laws.

One person (American, not French) objected when I referred to vote fraud, saying that “studies” showed there was no such thing. This is preposterous, but it is widely believed and circulated. First the “study” which underlies this claim, which originates from partisan sources, measures the wrong thing – criminal convictions for vote fraud. But of course most vote fraud never gets anywhere near a criminal conviction. Further, I told the fellow that I could introduce him to several people who work on election integrity, who have seen serious vote fraud with their own eyes, and I described some such instances. The gentleman shook his head, looked at me like I was an idiot, and said, “those are just anecdotes.” Amazing, to me. Eye witness reports are anecdotes, but the wispy presence of a purported study carries a lot of weight. Moments like that make me very, very happy I did not spend my life in the academic world. It is much better to be a lawyer, and during elections work with the Republican National Lawyers Association, whose members can tell you about many, many examples of vote fraud. And have no doubt: Vote fraud happens, it happens massively, it is a serious problem in American political life, and it undermines the legitimacy of the democratic process.

Several of the participants enjoyed a very pleasant lunch afterwards. The informal conversation was at an elevated intellectual level with give and take. I found this conversation far superior to the Q&A after the presentation, which had a more confrontational air about it. Still to be clear, the tone was courteous and did not have any personal edge to it, unlike what one often encounters from politically correct Americans.

One young woman is a doctoral student researching the Tea Party in two American cities. I will be interested to see what she concludes from her research.

Also, and as one expects in Paris, the food was very good. Prof. Noirot gently insisted I get the duck confit, which was a good call. The French people deliberating earnestly over the wine selection was also exactly as expected.

The entire event was nicely executed and everyone was very nice and courteous.

Afterward, I could not tell if my presentation had made any impact or not. However, Prof. Noirot assured me that my presentation had been “a breath of fresh air.” He later told me that the attendees were very grateful for my insight and the “very well-structured presentation.” I was of course pleased to hear this.

I am a somewhat unusual American conservative, since I am generally a Francophile. My first visit to France did nothing to undermine that.

Perhaps I will have the good fortune to return there on a similar visit at some point. I certainly hope so.

AFEA May 2014

American Politics: What future model for political America: manifestly gridlocked destiny or reinvented union?

Conventional wisdom has it that ever since New Deal policies were first carried out and fuelled conservative opposition to the growth of government, two increasingly distinct visions of American society have vied for public support and moved the nation closer to political gridlock with potentially dire economic consequences. The gap between these two visions is said to originate in the seemingly irreconcilable answers which they give to two basic philosophical and political questions: first, what are respectively the proper limits of government and individual freedom? Second, what role should the Constitution, and more generally the country’s Judeo-Christian heritage, play in marking out those limits?

On one side is the vision of the Founding Fathers who designed a system of government focusing on the primacy of inalienable individual rights particularly as defined in the Declaration of Independence. From this perspective, the need to protect such rights and obviate any risk of a “war of all against all” mechanically brings individuals together and societies into existence. That in turn leads to the creation of government whose role consists essentially in promoting the peaceful exercise of individual rights and freedoms. However because of the fallen condition of human nature as reflected in selfishness and the lust for domination, limits must be set to political power. It is therefore to neutralize the threat of tyranny that separation of power came to be adopted as a guiding principle by the Founding Fathers. The Founders regarded a written constitution as the essential tool to codify that separation both horizontally between the legislative, the executive and the judiciary, and vertically between the federal government and the States. Yet such a constitution could not on its own guarantee the success of a republican form of government based on the consistent exercise of individual freedom. The Founding Fathers therefore stressed the need to foster durably, both among the governed and their elected representatives, the notion of virtue described as the religiously-inspired moral ability to tame selfish impulses for the common good.

The opposing vision of American society has successively been conceived and partly implemented by Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and today Barack Obama. It is based on a more optimistic view of government’s ability to craft solutions to contemporary social and economic issues. Consequently, less divided government may well be needed to share out the country’s wealth more equitably, allow the exercise of individual freedom more fully particularly through universal access to health care and education, and adjust tradition to changing lifestyles. Seen from this perspective, the Constitution is dismissed as both obsolete and a political, social, and economic straitjacket that needs to be made more “living”, flexible, and inclusive to reflect society’s constantly changing norms.

The aim of this panel is to examine the actual scope and depth of the increasingly strident political, legislative, and judicial strifes that the two visions of American society seem to be generating both at the federal level and within the States. More particularly, the panel will look into whether such strifes reflect artificially partisan positioning naturally dictated by the rules of democratic electioneering, or whether they act as a check on the growing unification of the executive and legislative branches that may have been developing since the presidency of George W. Bush whenever either party has held the two branches simultaneously. In other words, is American society hopeless riven by divergent philosophical and political views of its nature and function, or is there still enough common ground for the American people to shape their country’s destiny consensually? If the survival of nations does depend on constant renewal, the panel will test the proposition that American renewal may ultimately rest on a combination of innovation and tradition in yet another rendition of E Pluribus Unum.

“I found this conversation far superior to the Q&A after the presentation, which had a confrontational air about it.” That may simply be your American background: I’ve witnessed Americans flinching from the frankness and directness of discussions after seminars in the UK, NZ and Australia, as well as on the Continent.

It sounds as though the reflexively leftist opinions of academics are as common in France as here. I am also a Francophile. I wonder how many realize that the excellent French Social Security system, including the best designed healthcare model in the world, in my opinion, was designed and written up by the Free French while in exile in London. When they returned, they implemented the whole system over a period of years, culminated by De Gaulle when he was President.

The failure of the French economic system is largely due to Socialism which has starved the Social Security system of revenue and required increasing proportions of tax subsidy to what was designed as a self-funded system. My series on health reform has used the French system as the best model I found for reform. Most discussion of reforms use small countries as examples and they do not scale up well. The French health care system was a new model that replaced a system much like ours before the war.

[Jonathan adds: Here’s the link to Michael Kennedy’s series of blog posts on health-care reform.]

“My series on health reform has used the French system as the best model I found for reform.”

Other knowledgeable people have told me this as well.

Other candidates for best model include Switzerland and Singapore, which as you note are small countries.

The French academics were confrontational but civil. It was not personal. I am going to clarify this in the post.

This sounds great.

And when I am in France, if I have the choice, I always order confit. For every meal, every time. I have been tempted to try to make my own but it is a lot of hassle.

I might add that the Free French had the opportunity to reform the healthcare system because the old system was destroyed by the Germans after 1940. The Free French had a blank slate to work with. I wonder if something similar will allow reforms like America 3.0 after a similar cataclysm.

“That may simply be your American background”

Let’s see… I’ve been told by Europeans that we Americans eat portions that are too large,

are inefficient for not using the metric system,

never walk anywhere,

have silly, derivative TV programs,

watch inferior sports like American football instead of soccer,

call football football instead of calling soccer football,

have worse music,

tip way too much,

don’t swear enough,

don’t drink as well as they do…

I’m sure there are more

The Aussie’s are confrontational, but at least they have sense of humor about it.

They also seem to make it over here more than the Huns and the Franks, so they’re used to it.

In 1977, on my first visit to Britain, we were standing in line on a Saturday morning to tour Parliament, including the House of Commons. Those were the pre-IRA days when you could do so. A tall official looking man came along and said, “Come with me, please.” He took us to the front of the line right at the doors. He said, “Stay here,” and left. After a few minutes, we realized he was collecting everyone in line who was speaking English. As the doors opened, we were the first group in the tour. He told us to keep up and stay with him. We got a great tour including some things that I doubt others heard. At one point, he described the day after Common had been bombed in the Blitz. He said, “Winston was standing there, and I was there.” He was a retired policeman supplementing his pension with work as a tour guide. He told us that he didn’t want French or Germans in his group. The Germans, he said, “Couldn’t get here on their own,” and he wasn’t helping them. He much preferred Americans.

He got a good tip from me.