Lewis, William, The Power of Productivity: Wealth, Poverty, and the Threat to Global Stability, U of Chicago Press, 2004. 339 pp.

[cross-posted on Albion’s Seedlings]

Preliminary headlines on the upcoming riot season in Paris are starting to appear, recalling the difficulties that European countries face in boosting their economic performance: reducing unemployment and increasing economic growth. Fareed Zakaria’s article in the Washington Post earlier in 2006 entitled the Decline and Fall of Europe is a quick and readable summary.

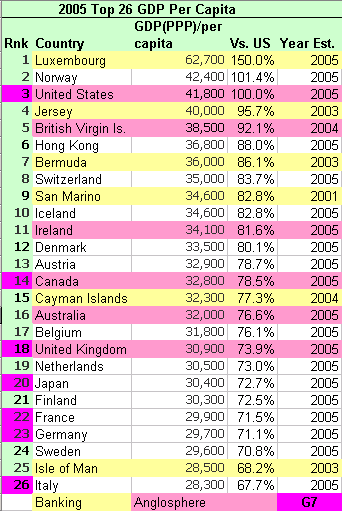

Zakaria quotes a particularly interesting OECD report called “Going for Growth” that shows Europe, rather than catching up to America in per capita GDP, has in fact been falling behind over the last 15 years. Efforts to catch up, while noteworthy and politically difficult, have essentially failed. When the GDP figures are adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP), from country to country and around the world, we end up with shocking tables like the following:

Source: CIA World Factbook

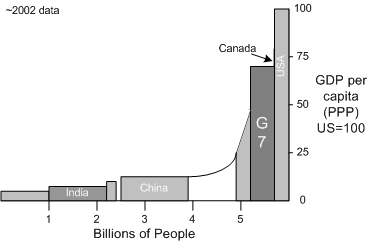

and this:

Source: Adapted from Lewis, The Power of Productivity, 2004.

The United States doesn’t simply lead the world in GDP per capita (PPP adjusted). It is in a class (fully acknowledging its size) entirely by itself. Adding 1 million net citizens every nine months (one every 13 seconds), America is extending its lead in prosperity over not only poor and moderately wealthy nations, but over virtually all of its erstwhile companions on the “heights” of Mount Prosperity. Next-door neighbour Canada is the only eight digit population close to the US, coming in at 78% of US per capita GDP (PPP adjusted).