The Battle of Cowpens captures American strategy in microcosm. Meet Daniel Morgan, the “Old Waggoner”. Morgan was a Virginia frontiersman whose first taste of military life came during the French and Indian War. He also learned to hate the British: after he punched a British officer, Morgan was whipped 499 times. He survived this experience, leaving him stronger and thirsting for revenge. So Morgan was ready for action when, after Lexington and Concord, Virginia made him captain of a company armed with accurate but slow-loading rifles for sharpshooting instead of the fast-loading but inaccurate muskets issued to regular infantry. He served with distinction in campaigns like the abortive liberation of Canada and Saratoga, rising to the rank of colonel with command of a regiment. But, repeatedly passed over for promotion to brigadier general and racked with pain from various ailments, Morgan resigned his commission and went home. He refused repeated requests to serve again until the American disaster at Camden finally drew him back into service. Morgan was quickly promoted to brigadier general by Nathanael Greene, commander of American forces in the South.

Morgan was blessed with a stereotypical British antagonist. Banastre Tarleton was a British lieutenant colonel famous for his aggressive cavalry tactics and his propensity for killing American prisoners and civilians. Tarleton was the fourth son of a prosperous slave trader, foreshadowing his later taste for innocent human flesh. Having squandered most of his inheritance on a life of aristocratic dissipation, Tarleton, reflecting the proud British tradition of military meritocracy, bought an officer’s commission. Recognizing that war could be highly profitable to a broke nouveau riche aristocrat on the make, Tarleton volunteered for service in King George III’s War on Freedom in 1775. Throughout the early years of the American Revolution, Tarleton served with distinction, even unwittingly helping the Americans by relieving them of Charles Lee. Tarleton transferred to the Southern theater of operations in 1780, where his talent for murder found full expression. His most notorious crime was a massacre of surrendering Americans at Waxhaws: “Tarleton’s Quarter” became notorious.

The road to Cowpens began when Greene divided his army to better gather provisions while showing the flag to the people of the Carolinas. Morgan was dispatched with ~600 men to the Carolina backcountry. ~400 of his men were American regulars (“Continentals“) while another ~200 were militia with past experience as regulars. Morgan was joined en route by other militia, including partisans who’d been harassing the British and their American quislings (“Loyalists” or proto-Canadians). The force grew to between 800 (Morgan’s estimate) and 2000 men. Morgan’s command was primarily made up of infantry but included ~200 cavalry under the command of George Washington’s second cousin William Washington.

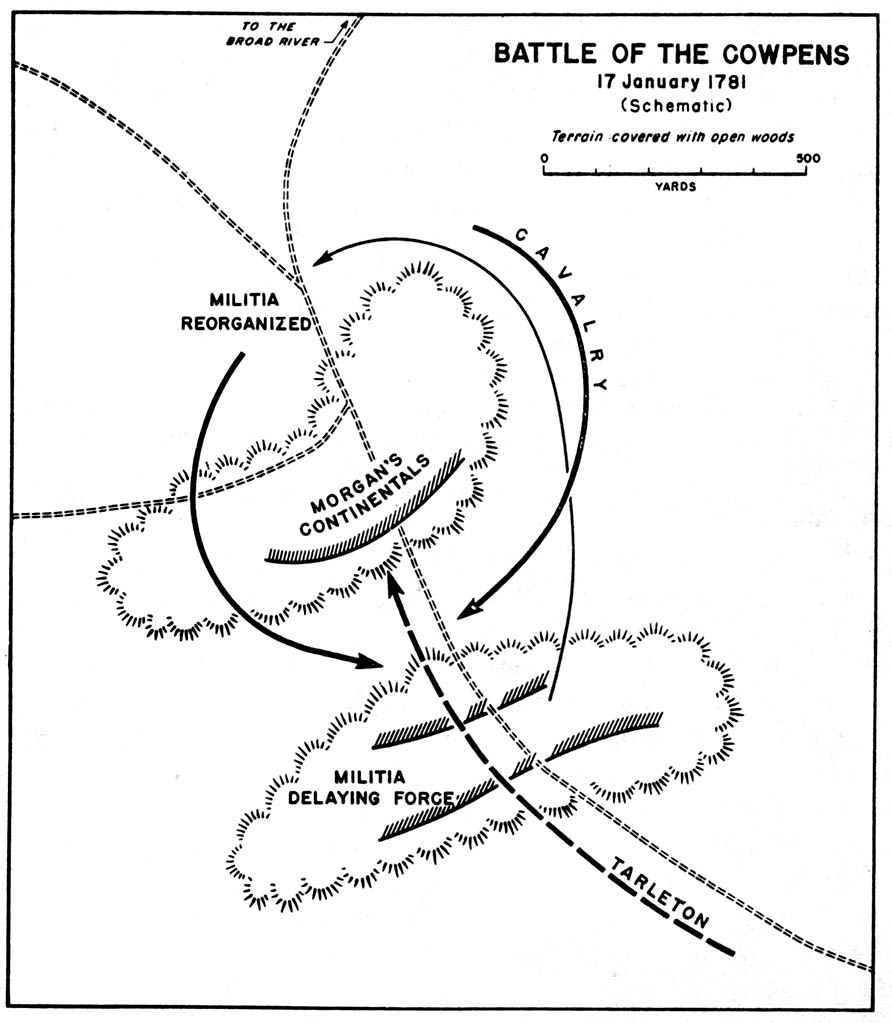

Lord Cornwallis, commander of British forces in the South, dispatched Tarleton to intercept Morgan’s force. Tarleton had ~1,150 English, Highlanders, and American traitors under his command, ~300 of whom were cavalry, and two three-pounder cannons served by 24 artillerymen. Tarleton moved on Morgan’s forces aggressively and Morgan retreated northwards. However, Tarleton caught up with Morgan at a cow grazing area called the Cowpens in north central South Carolina. His scouts found Morgan’s army pinned between the Broad and Pacolet Rivers, with no open line of retreat. Even better, Tarleton’s scouts reported that Morgan’s forces were primarily militia. American militia had a strong reputation for one thing: running away as soon as shooting started. In Tarleton’s experience, a little cannon fire and a good bayonet charge were sufficient to route any American militia, especially if you were quick about it. So, even though his army had less than four hours of sleep and hadn’t eaten for 48 hours, Tarleton decided to attack immediately. He formed his infantry up and sent them head on at the American position, keeping ~200 infantrymen in reserve and ~250 cavalry for pursuing the fleeing rebels after they were routed.

Tarleton first sent his dragoons to disperse a line of American skirmishers in front of the American position. Many of these skirmishers turned out to be sharpshooters and they drove back the dragoons. Tarleton immediately sent his main body of infantry up in response to this repulse and the skirmishers fell back on another line of militia to their rear. Unusually, this militia didn’t immediately run away at the sight of oncoming Redcoats. They actually stood their ground, fired two volleys, and inflicted substantial casualties on the British. But the British kept on coming and the militia fled. The British, sensing victory, pursued.

Then they ran into a well-organized line of Continentals. The Continentals fired into the disorganized British, causing more casualties. At the same time, one body of retreating militia suddenly turned around and fired into a column of flanking Scots. Then an American officer shouted, “Charge bayonets!” This was a novel experience for the British. Americans fled bayonet charges. They didn’t make bayonet charges. The British, hungry, tired, surprised, and confronted by the potency of American manhood, turned and fled. While they were fleeing, they were hit on their right flank by American cavalry under the command of Washington and on their left flank by the “retreating” militia.

Redcoats surrendered or were cut down. Many fell to the ground out of shock. The few that resisted surrendered after being completely surrounded. Tarleton was stabbed in the neck by Mel Gibson with a bayonet ordered his last remaining unit of cavalry to charge but they fled the field. Tarleton managed to scrounge up another forty cavalry and tried to retrieve his artillery. He failed.

(YouTube)

Tarleton was confronted by Washington, who called out, “Where is now the boasting Tarleton?” and swung his saber at him, cutting Tarleton’s hand. Tarleton shot Washington’s horse out from under him like the shopkeeper he was and fled.

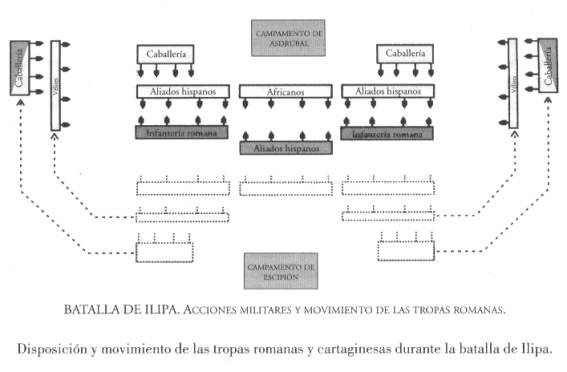

The battle was over in an hour. In the course of that hour, Tarleton went from the next Prince Rupert to the latest Gaius Terentius Varro. Tarleton lost 110 killed and 712 captured, an 86% casualty rate. Perhaps it was to be expected. No one ever expects the double envelopment. Tarleton had been lured into a second Cannae.

The battle of Cannae is the benchmark of tactical excellence. Alfred, Graf von Schlieffen, infamous drafter of the precursor to the Schlieffen Moltke Plan, was obsessed with Cannae, even writing a monograph on the battle. It could be said that World War I was precipitated by Hannibal envy.

Most military leaders never get a chance to produce a Cannae. In Patterns of Conflict, John Boyd even argued that Cannae’s siren call should be resisted. Boyd argued that the battle of Leuctra was a better model since the oblique order was sufficient for morally disrupting the enemy. A double envelopment was unnecessary showboating.

B.H. Liddell Hart argued that the battle of Ilipa was a better Cannae than Cannae.

Yet Daniel Morgan, backwoodsmen, leader of a ragtag group of militia, pulled off the highest form of battlefield art. And it was all made possible by one man: Banastre Tarleton.

Morgan’s battle plan was designed to exploit Tarleton’s contempt for American forces. More importantly, it was designed to remedy the underlying reasons for Tarleton’s contempt. Morgan intentionally trapped his own army against two flooding rivers. This was so his militia couldn’t run away, leaving his Continentals high and dry. Figuring that Tarleton’s contempt for American militia would cause him to eschew complicated maneuvering in favor of a simple head on frontal assault, Morgan then arranged his infantry in three lines. The first line would be made up of elite skirmishers to delay and harass the oncoming British. These skirmishers would then disperse to reveal a second line of militia. Morgan turned this militia’s usual military uselessness into a military advantage. First, the militia would mask the third line. Second, the militia would only be required to fire two volleys before they were allowed to run away. Third, the sight of the militia running away would draw the British after them, throwing them out of formation in their thirst for red, red American blood. Then they would hit Morgan’s third line. This third line would be composed of Continentals, professional soldiers who had been trained in the use of the bayonet by Baron von Steuben, making them honorary Prussians. They were positioned at the top of a hill, meaning that the British would suddenly run into them as they were marching uphill. At this point, Morgan figured, the British would have been worn out by their march uphill through the first two lines. All it should take is the Continentals firing into the British infantry and then charging them with the bayonet while, at the same time, Washington’s cavalry hit the British right and the reorganized militia from the second line hit the British left. The British would be shattered.

Everything went according to plan except for Tarleton’s escape from Mel Gibson’s bayonet.

Morgan successfully combined the two major schools of American strategy: the unorthodox Magic Bullet strategy and the orthodox strategy of the Headless Chicken. The Magic Bullet strategy is based on harnessing the power of the Chosen One or the Select Few. Strategy is formulated by the lone genius or elite few who carefully, precisely, and exactly bring about victory through dedicated professionalism, specialized craft, sheer brainpower, and inspired foresight. The Headless Chicken theme harnesses the rough, predominantly uncoordinated actions of the many to produce many strategies through a process of emergent order. This diverse thicket of strategies forms an adaptive tumult that meets all challenges by simply adapting faster than challenges can arise. The Headless Chicken road to victory is rough, amateurish, and poorly targeted. It usually triumphs through sheer grit and by inflicting attrition. The Magic Bullet is the hammer and the Headless Chicken is the anvil. Victory is forged between them.

Morgan himself came from a Magic Bullet background. As a commander of riflemen, he had led one of the Continental Army’s elite forces, capable of decapitating a British force by unsportingly picking off officers and NCOs from the safety of the woods. Morgan’s riflemen provided the crucial unorthodox element that brought victory over Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne at Saratoga. However, on a few occasions during the battles at Saratoga, Morgan’s riflemen were caught out in the open by British regulars and forced to beat a hasty retreat back to the safety of the woods.

Experiences like this taught Morgan the advantages and disadvantages of the Magic Bullet approach. Under the right circumstances, the Magic Bullet could deliver sudden strokes that brought victory. But the Magic Bullet couldn’t stand up to sustained attrition or it would quickly wear away. This is where the mass of the Headless Chicken was needed to secure victory. It absorbed enemy attacks while the Magic Bullet was prepped to deliver the killing blow. The Headless Chicken couldn’t deliver victory by itself either. It needed the Magic Bullet to stiffen its resolve, to provide specialized services, and deliver the killing blow through sudden shock. Without this elite backbone of iron, the Headless Chicken was liable to run around in disarray before retreating as a mob.

At Cowpens, Morgan used his Magic Bullets to provide leavening and to deliver the eventual coup de grace. He used the Headless Chicken to wear the British down but not to absorb the full impact of a Redcoat assault. The Headless Chicken was also useful for attacking British forces after they had been thrown into disorder. In a melee between disorganized mobs, the bigger mob usually wins and no man is a bigger hero than when he’s running down confused and emotionally shattered enemies.

There is a broader lesson here for contemporary American strategy. Neither the Headless Chicken or the Magic Bullet is sufficient by itself. You need both generality and specialty, mass and precision, orthodox and unorthodox, amateur and professional. The foundations of strategy must be broad and spread throughout the body of the American citizenry. Strategy must be made robust through the extreme redundancy of local initiative. Yet a highly trained cadre of with specialized skills must be maintained. Knowledge of those specialties must be widespread but only a few can dedicate their full time and attention to mastering them. However, American strategy cannot be outsourced to the few or the one. There must not be a critical bottleneck that fails in times of stress. American strategy making must be widespread. Its basic principles must be widely understood. While the talents and skills of the one or the few must be used for the common good, the American system must not rely on the providential appearance of genius to rescue it. No Magic Bullet will deliver us from evil by itself. Strategy works best when there are many hands working to sustain it.

ADDENDUM:

Committee of Public Safety regular T. Greer links to these great images of Cowpens:

Marvelously informative and well written. Thank you.

So there were fewer than 5,000 men fighting, as opposed to 150,000 at Waterloo or Austerlitz? I haven’t seen any indication that any battle in the American Revolution involved more than 30,000 men total. We were really the beneficiaries of logistics. The British and their allies could support the armies needed to crush Napoleon, but the English Channel not as wide as the Atlantic.

Given the numbers involved, had the British succeeded in restoring the colonies to obedience (no doubt having hanged a number of rebels), this campaign would have been as well-remembered as the War of the Austrian Succession. That is, until the second revolution.

Is this one?

Magic Bullet: George Marshalls little black book, with a list of superannuated majors and lt.cols. who went to three and four stars from 1940-45. Headless Chicken: 8+ million man army of civilians in uniform, making sh*t up as they go along.

Or this?

Magic Bullet: A small number of panzers; Headless chicken: a big mob of landser staggering along in the dust cloud miles behind the tanks.

@Mitch

Britain sent the largest expedition ever dispatched to the New World from the Old World in 1776. Over 20,000 British soldiers faced about 19,000 American defenders around New York City. The British smashed the American forces and nearly crushed the rebellion with one swift stroke. Washington’s winter campaign in New Jersey in 1776-1777, with two victories at Trenton and one at Princeton coupled with numerous partisan attacks exposed Britain’s fundamental weakness. Not only was the North American seaboard far from Britain but it was as large as Western Europe and populated by a hostile population. Successful American warfare and diplomacy in 1778 brought France into the war, soon to be followed by the Netherlands and Spain. This split Britain’s forces among numerous theaters of war, including facing the possibility of a French invasion of the British Isles themselves in 1779. By the end of the war, Britain had mobilized almost 1 million men. Given the fact that it was fighting alone, with no allies, all over the world, Britain’s failure to crush the Americans is quite understandable.

@Lex

Yes.

Your example of Marshall illustrates the Headless Chicken vs. Magic Bullet issue pretty well. The all professional war fighting we use today dates back to the landing of American forces in Cuba in 1898. It was such a mess that many Regular Army officers swore that the volunteer companies raised by prominent citizens would never be used again. No more Rough Riders. Any future mobilization of forces would happen entirely within the structure of the Regular Army. The Regular Army tried to kill off the National Guard and replace it with an Army Reserve controlled by the War Department but Congress fought off the attempt and made the National Guard and a new Army Reserve the back up formations for the Regular Army. The National Guard was forced to train up to the same standard as the Regular Army.

After America entered World War I, Theodore Roosevelt started raising his own volunteer company. However, the Regular Army went to Thomas Woodrow Wilson and argued that expanding the Regular Army through a draft would be preferable to raising a wide variety of ad hoc volunteer companies led by political generals. Since TR was a political opponent, Wilson was happy to accede to the Army’s request. The blueprint and organization developed for the Regular Army in World War I set the course for the American Way of War up to our present day. Marshall was a definite reflection of this Regular Army preference.

It could be argued that pouring American recruits into the tight straight jacket of the Old Regular Army suppressed small unit initiative when compared to the stronger small unit initiative in the Reichswehr/Wehrmacht. The Regular Army in 1917 (and even in 1939) was a hidebound organization populated by a class of people that most American civilians of the time frankly considered losers. In response, the Old Army was a rather authoritarian anomaly within American society, even considering the particular requirements of a military organization. The men who became high quality officers and NCOs often went into other, more profitable civilian fields. For higher quality officers of the time like Marshall or Eisenhower, making the military a career came at great personal sacrifice even in peacetime. Patton was unusual in that his great personal wealth made military service quite affordable. Volunteer formations may have had more initiative and innovative instinct than Regular Army formations. Interesting question.

Um, hadn’t the British dude ever heard of the Battle of Hastings? In, you know, the year 1066? About the tactic of a false retreat to lure an attacker into a trap? Dude?

It’s interesting how much of the story of the Cowpens parallels the Little Bighorn fight with Custer cast as the confident Tarleton and the combined tribes as Morgan. Cannae for sure.

My childhood was spent crawling around, through, and under Fort Pickens, in the panhandle of Florida.

Now I know how it got its name.

Dennis, I would say Custer fought the opposite of Cannae. He did not charge but set up small outposts along the ridge line. His main body was placed in the center and they had the high ground. I was last there many years ago but, at that time, it was the most impressive battlefield I have seen, and I’ve seen a few. You stand there by the monument, looking down the slope to the river in the distance. You can almost hear the Indians coming. Custer was foolish in bringing such a small number into the range of a huge force with no possibility of reenforcement. It probably had more similarity to the Alamo although it wasn’t intentional.

Michael,

I meant that the Indians executed the Cannae. Reno’s force rode out in a charge but fought initially as Dragoons (as I think was logical in his situation). Custer, whatever he was trying to do, got himself trapped on a ridge surrounded by ravines. The Indians, by use of the ravines were able to surround him and wipe out the command.

The parallels have to do with his underestimates of the fighting abilities of the Indians and, so, his willingness to attack with a greatly outnumbered force which he then further weakened by dividing his forces. The Indian strategy may well have been of the Headless Chicken variety, but it was well and forcefully executed which, as Patton said, is the critical hinge of success in battle.

Exellently presented essay, by the way.