Okay, this is my first post since I joined up as a member of Chicago Boyz, and I’m delighted to be here — thanks to Zen and Lex for the introduction and invitation!

I’ve had a couple of guest-posts here already, one for the Afghanistan 2050 roundtable and one on the topic of religion and violence — a perennial interest of mine — and I’d like to take the opportunity now to address another of my passions.

*

I’m deeply interested in games and play.

It’s my contention that play is the mode in which children learn and masters create and express themselves. And with the coming of modeling, simulations and scenario-planning I think we’re deep in a movement away from the binary opposition of theory and practice and into a zone where play occupies an intermediary position between the two — with simulation and modeling giving us the opportunity to practice our theories in a “safe” zone which allows us to learn positive lessons from both positive and negative decisions, without suffering from the negative consequences of poor decision-making in the “real world”.

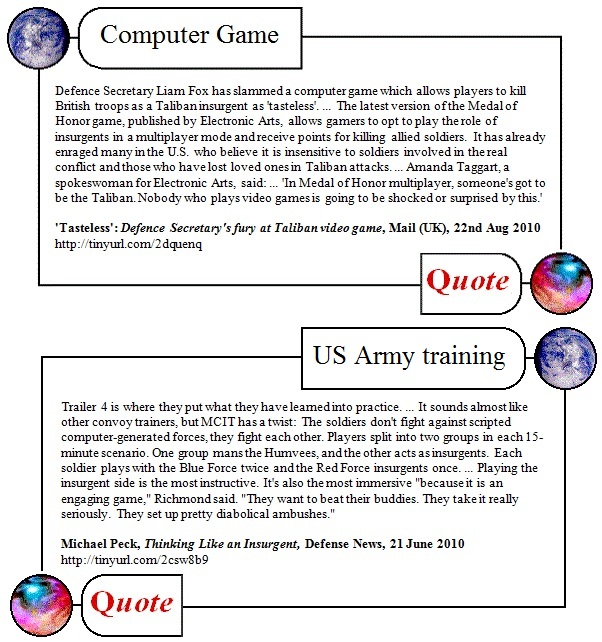

I try to keep tabs on games of war — and peace — because of this, and would like to offer you one of my “DoubleQuotes” based on a couple of things I read recently. The idea behind these DoubleQuotes is to drop two quotes into the mind simultaneously, like two pebbles dropped into a pond, and see how the ripples intersect and interact.

Here’s today’s example:

I’m not arguing for or against anything here, just inviting you to consider the implications of two related but different news items: one one of them, the US army is thinking of banning a game because it allows players to play an insurgent role, in the other the army is using insurgent role-playing as part of training.

Josh at Al-Sahwa has an interesting recent post on the same conundrum, and links to this CNN video, which shows some of the training in action.

What do you think? It’s your thoughts I’d like to get at here, my own contribution is mostly intended as an opening salvo to get a conversation going.

*

So: should Paul van Riper have been allowed to play Red in a game like Millennium Challenge 2002?

I know, my own bias is beginning to show … I favor modeling, scenario-planning and gaming with as much intelligence and creativity as possible.

Frank Herbert, noted for his creation of the Dune series and his big pouffy beard, had a series of stories involving a Bureau of Sabotage (BuSab).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bureau_of_Sabotage

Per Wikipedia:

Institutionalized red teaming (or benign sabotage) would be nice for our own governmental functions but red teaming always comes with the risk of focusing on defeating the Near Enemy and neglecting the Far Enemy.

The first quote seems to apply to the British defense establishment, not the US Army. Right?

Art:

You’re right, of course. Yes, the first quote has to do with the British. I put the two quotes together before I read that the US has its own problems with the game, and is banning its sale on US army bases:

My basic point remains the same — but thanks for catching the error!

M. Fouche:

Thank you for the pointer to Frank Herbert’s BuSab.

As you may imagine, I’m a big fan of the Dune series, not least because it deals with a whole slew of topics in religion that interest me greatly — prophecy (the Bene Gesserit), ecstatic intoxication (the Spice), and Mahdism.

I’m also reminded of Tolkien’s creation story, the “Music of the Ainur”, in The Silmarillion. Counterpoint as in Bach, chiaroscuro as in Rembrandt and dramatic tension as in Shakespeare all seem to demonstrate the power that can be derived from a skillful use of “opposition”.

http://richardyates.org/bib_russo.html

I suppose some people are afraid that certain types of play may become a kind of indoctrination. But “charismatics” and recruiters will look for the weak in any way they can, so keeping young people away from the video games won’t help. Or it’s just plain disrespectful.

I just made that up. Is there anything to it? I’m on the “we need to play so we are not behind the curve” side, myself.

– Madhu

Okay, I wasn’t talking about army recruiters in my above comment, just to be clear. I meant recruiters for something more sinister.

– Madhu

Interesting comparison. I believe this is one of those circumstances in which context is crucial.

There is no better way to analyze the tactics of one’s opponent than to occupy their position in a simulated environment. The Navy’s Top Gun program does exactly this, as does (I believe) the Air Force; military exercises have separated soldiers into opposing forces so as to train how to, and how not to, overcome an equal adversary. Putting soldiers in the role of insurgents is a necessary and appropriate exercise: whether in the field, in the classroom, or in a computer or otherwise-simulated environment.

Not so, pimply-faced teenagers or their older counterparts. I recognize that the free market is called that for a reason. I recognize also the outrage that military officials and military families express as valid—indeed, my brother is a Marine officer halfway to Afghanistan for another tour, having completed his first in Iraq. Under no circumstances would I play such a video game in the adversarial role, nor purchase same for my children. For the military to ban nonprofessional applications of this software is reasonable. Military service has strict boundaries: that’s why they call it ‘service’, and not ‘free-for-all’.

Let software engineers make what they will (within the bounds of human decency). Let people freely express their disgust, and parents exercise their guidance. It’s the worst of systems, to paraphrase Churchill—except for all the others.

The United States’ great strength is its willingness to undertake unpleasant changes and challenges with less flinching and denial than just about anybody else. Not permitting the game is a flinch. I think it’s one we can survive but you never know…

You might find Red Team Journal worthwhile:

http://redteamjournal.com/

Charles Cameron wrote:

“It’s my contention that play is the mode in which children learn and masters create and express themselves. And with the coming of modeling, simulations and scenario-planning I think we’re deep in a movement away from the binary opposition of theory and practice and into a zone where play occupies an intermediary position between the two ”” with simulation and modeling giving us the opportunity to practice our theories in a “safe” zone which allows us to learn positive lessons from both positive and negative decisions, without suffering from the negative consequences of poor decision-making in the “real world”.”

http://www.amazon.com/Play-Shapes-Brain-Imagination-Invigorates/dp/1583333339

Hi Mahdu:

A pleasure to talk with you again. And it looks as though I need to read Richard Yates — thanks for the pointer.

Both Hezbollah and the US DOD use games for recruitment. Hezbollah, for instance, has a 2007 game called “Special Force 2: Tale of the Truthful Pledge” which a spokesman admits has training potential:

On the US side:

Mlyster, TMLutas: Thanks for your comments.

Zen: Thanks for the pointer.

I’d just like to express my delight at the conversation here…

More shortly.

I gave a presentation on games of war and peace to one of Stephen O’Leary’s classes at USC’s Annenberg School one time, and the sheer range of issues that can come up for discussion is amazing.

I’ll break this post up a bit, so I don’t get too tangled up in my own HTML.

First, there are some pretty trivial “quickie” games.

How does killing bin Laden compare with killing Obama? I doubt that Special Forces wants to recruit players of the first game, or that the Secret Service bothers to track those who play the second — and then there’s Barney. How do you feel about killing Barney the dinosaur? All three games are pretty much the same as games, and nobody believes killing Barney is “real”.

FWIW, there’s even a GURPs manual for a game called Barney Jihad:

These are not particularly realistic games, and perhaps the choice of target doesn’t make as much diffrerence here as it would in more complex games…

Is it okay to torture prisoners in a game? In Al Qaidamon:

This is another of those quickie games – but the issue of the rules of war is a real consideration for serious game designers. America’s Army, for instance, wouldn’t let you torture people:

Under Siege also claims to follow appropriate rules of engagement:

Covering the same conflict from a human rights perspective, we have Safe Passage:

And at the peacemaking end of the spectrum, still dealing with the Israeli-Palestinian issue, there’s my friend Asi Burak’s prize-winning game, Peacemaker:

It’s quite a spectrum”¦

And then there’s academia — something of a realm unto itself. There’s a “ton of material at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies, where the games industry meets the military.

James der Derian’s Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network is IMO the key reading in this area.

You’ll find the history of wargaming from Kriegspiel up to and including the beginnings of the ICT and America’s Army in Lenoir and Lowood’s Theaters of War: The Military-Entertainment Complex.

And then there are scattered pieces of the puzzle all across the acadedmy — Patrick Rogers-Ostema’s 2010 MS thesis Building and using a model of insurgent behavior to avoid IEDs in an online video game, for instance, isn’t about voiding IEDs in a video game, although the title reads that way — it’s about using a video game to learn how to train soldiers to avoid IEDs in real life.

Okay — one final short post and then I’m done — but I don’t want to leave the topic without some mention of Chess and Go.

For Go (and games of war), let me point you to Scott Boorman’s book, The Protracted Game: A Wei-Ch’i Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy.

And I’d like to present this graphic of a chess game in al-Andalus between Muslim and Christian as an example of Chess (and games of peace).

Phew! I’m done for now.

Not to take the comments thread too far off-track, but the only Richard Yates I’ve read is Revolutionary Road. I was prepared to hate the novel thinking it was just another pan of American middle class culture as soulless and deadening.

I know it’s been read and reviewed that way, but honestly, I thought it was something altogether more heart-breaking and subtle. I thought it was about the sadness some feel in life because they dreamt dreams – big or small – that just didn’t happen. I think his novels are about sadness.

– Madhu

Er, the one novel I read, I mean.

– Madhu

Thanks, Madhu — and my apologies for mis-spelling your name above. I haven’t read anything of his, but you’ve persuaded me to try.

And today brings a new twist to the “games of war and peace” angle…

Spencer Ackerman leads off his Wired post How To Spot A Whitewash In Army’s Death-Squad Inquiry:

As I said in my comment over there, I don’t think that’s quite right: I think part of the horror here lies in the phrase “hunted and killed Afghan civilians for sport” — that little phrase “for sport” is the give-away.

If the story as recounted is true, the soldiers were “playing a game” – as in the story The Most Dangerous Game first filmed in 1932 with Joel McCrea and Fay Wray — or for that matter in the movie Surviving the Game with Ice-T, Rutger Hauer, Gary Busey, F Murray Abraham.

As far as I know, death squads kill political opponents, or people whose lands they wish to seize. Killing just for the thrill of the kill is in a whole other dimension.

*

The most honorable use made of the “hunter hunted” archetype may well be Geoffrey Household’s novel Rogue Male, described in Household’s NYT obituary as:

Pretty clearly, the dictator in question (the novel was published in 1939) was Hitler, as Household later acknowledged.

Attempting to assassinate Hitler in a “big-game hunting” manner comes closer to the “targeted killing” idea and the recent US finding approving the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki.

Itself a matter of some contention.

@ Charles Cameron:

I heard the following story on NPR yesterday and it gave me the chills. This is complicated business, isn’t it?

“In the fall of 1958 Theodore Kaczynski, a brilliant but vulnerable boy of sixteen, entered Harvard College. There he encountered a prevailing intellectual atmosphere of anti-technological despair. There, also, he was deceived into subjecting himself to a series of purposely brutalizing psychological experiments — experiments that may have confirmed his still-forming belief in the evil of science. Was the Unabomber born at Harvard? A look inside the files.

http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/2000/06/chase.htm

– Madhu

In case the relation of my last comment to the current thread isn’t clear, I’m wondering about the psychological impact of different types of game-playing.

– Madhu

Hi, Madhu:

I’m pretty sure that “play” is akin to “flow” in the sense in which CsÃkszentmihaly uses the term, and games and play go pretty deep into the human psyche. Carl Jung told his friend the novelist Laurens van der Post, “One of the most difficult tasks men can perform, however much others may despise it, is the invention of good games and it cannot be done by men out of touch with their instinctive selves.”

In very simple, cartoonish games like the ones I linked with above where you “kill” Barney, or Obama, or bin Laden, the separation between the “pretend world” of the game and the “real world” outside it is pretty clear — but the more sophisticated and “realistic” a game gets, the easier it may be to forget the distinction, so that the symbolic representation elicits real feelings…

But we’re getting into the realm of how the arts work — and I’d refer you here to Oatley’s paper, “Shakespeare’s invention of theatre as

simulation that runs on minds”, downloadable in .pdf here — and to sources such as Abhinavagupta and Ibn ‘Arabi.