Friday, August 2, 1923 was to be Coolidge’s last day of vacation at Plymouth Notch. He had posed for photographs for the small pool of reporters who covered his doings. They had shown him chopping away rot from a maple tree, wearing his suit pants and vest but bowing to the informality of the occasion by removing his suit coat. He had previously worn a woolen smock that had belonged to his grandfather for such chores but, recently, there had been accusations that it was a costume of some sort. He remarked that “In public life it is sometimes necessary in order to appear really natural to be actually artificial.”

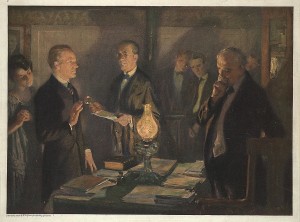

The Coolidge family retired early. A telegram from San Francisco conveying the news of the president’s death reached reporters staying in a boarding house in Bridgewater, Vermont. They hastened the eight miles to Plymouth Notch and knocked on the door of John Coolidge’s house. He awakened his son who then dressed and came downstairs. He was informed in a telephone call from his father’s store to Secretary of State Hughes that the oath of office could be administered by a notary. Coolidge returned home and, at 2:47 am, his father administered the oath of office as president.

The nation’s newspapers carried drawings and paintings of the scene the next day. It is still the only instance of a father administering the oath of office of president to his son and of a man taking the oath at home. The house was small and lacked indoor plumbing. It was typical of Coolidge in its lack of pretension and the image was a powerful one to begin his presidency. After the oath was administered, the Coolidges returned to bed, also typical. They arose at 6 am and began the trip back to Washington with a stop at his mother’s grave in a nearby cemetery. These symbols would stand him in good stead when the Harding scandals began to fill the newspapers in the months to come.

Harding’s body was returned to Washington on August 7 where he lay in state in the Capitol. Coolidge issued a proclamation for a day of national mourning and it was apparent that Harding was genuinely liked by the public. The funeral was in Marion, Ohio on August 10.

In 1923, the presidency was very different from what it became under Hoover and Roosevelt. Coolidge greeted White House visitors in person, the last president to do so. He had one secretary and no aides. His telephone was not on his desk but in a nearby booth and unused. He did not know how to drive a car. He had carefully cultivated his image, even to his famous lack of small talk. At a dinner party while vice-president, a woman next to him at the dinner table told him she had a bet with her husband that she could get him to say at least three words. His reply was, “You lose.”

Now, he was president. In 1924, he told William Allen White that “A lot of people in Plymouth can’t understand how I got to be president, least of all my father.” He added, “Now a lot of those people remember some interesting things that never happened.” White’s comment was that Coolidge never grinned after his jokes. This misled some people into thinking he was dumb. Rural Vermonters appreciated his wit but many of the intelligentsia did not. He did not suffer fools gladly, for one thing. Once, after a long and animated conversation with financier Bernard Baruch, he asked why Baruch was smiling. The financier replied, “Mr President, you are so different from what people say you are. Your smile indicates both amusement at that and interest — and I hope friendliness.” Baruch added, “Everybody says you never say anything.” “Well Baruch,” Coolidge replied, “many times I say only ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to people. Even that is too much. It winds them up for twenty minutes or more.”

One of Coolidge’s most famous sayings was made to Hoover, whom he disliked, on the latter’s ascension to the presidency in 1928. ” You have to stand every day three or four hours of visitors. Nine-tenths of them want something they ought not to have. If you keep dead still they will run down in three or four minutes. If you even cough or smile, they will start up all over again.” Will Rogers appreciated Coolidge’s dry wit. “Mr Coolidge had more subtle humor than almost any public man I ever met. I have often said I would like to have hidden in his desk somewhere and just heard the sly little digs that he pulled on various people that never got ’em at all.”

Another story concerned his wife’s asking about the preacher’s sermon in church that morning. “What did he talk about.” His reply was concise. “Sin.” When asked for more detail, he replied, “He’s against it.” Someone told him the story one day and his reply was “It would be better if it were true.” Still, these stories indicated a warmth toward him that was widely held and that would serve him well. His son, Calvin, inherited the family wit and showed it one day when working at a summer job as a laborer. One of the other boys said, “Gee. If my father was the president , I wouldn’t be working here !” Calvin replied, “You would if your father were my father.”

Harding had held twice weekly press conferences and Coolidge assured the reporters that would continue. He held a total of 520 press conferences in the next five years. The questions were submitted in writing and he answered those he chose to. The answers were to be attributed to a “White House spokesman.” He was genuinely liked by reporters and commented on his excellent relations with the press in his Autobiography. He needed a secretary and was advised well by Congressional leaders to hire C. Bascom Slemp, a 53 year old former Congressman and master political strategist. Coolidge faced a difficult relationship with his Republican colleagues in the Senate. Harding had been one of them and was a friendly man; neither was true of Coolidge.

There was Frank Stearns, an old supporter from Massachusetts. Coolidge liked to have Stearns with him even though both might not say a word. He thought better when Stearns was there. One day, after an hour in which neither said a word, Stearns rose to leave and Coolidge said, “Stay a while longer.” Dwight Morrow, a friend from Amherst and now a partner at JP Morgan was another close friend. Murray Crain was gone but his assistant, William Butler, was there. He was RNC chair, with help from Coolidge, and, when Lodge died, Butler took his place in the Senate. House Speaker Gillett was the fourth of the “Massachusetts gang.” Aside from them, Coolidge had few friends.

Mellon and Hoover with Coolidge

He retained Harding’s cabinet although several left under a cloud by 1924. The last to leave was Hoover, to run for president in 1928. Coolidge respected but did not like Hoover, calling him “Wonder Boy.” His most trusted adviser was Treasury Secretary Mellon. At their first meeting, Mellon told the president he had come to resign. The president said, “Forget it.” Coolidge was the last president to write all his own speeches and they have stood up well over time. He was also the first to use radio in reaching out to the public. When asked for a theme of his administration, he answered “stability, confidence and reassurance.” We are currently seeing how important the lack of those qualities may be in economic recovery, or the lack of it. It is possible (more of this later in a summing up) that his decision to retire in 1928 may have led to the Great Depression as Hoover was an active progressive and Roosevelt followed his lead almost completely. The depression of 1920-21 was the last to be treated with Laissez Faire economics. The 1929 crash and depression might have been short as the country was already emerging in 1932 in spite of Hoover’s misguided policies. We will never know.

One area where Coolidge enjoyed the approbation of everyone was with his wife, Grace. She was witty, attractive and provided a useful contrast to her husband. Their two sons were also attractive and a positive aspect of his presidency although that was to be dashed during the summer of 1924. Coolidge had four months to prepare before he would be obliged to state his policies before Congress. Major problems included the war reparations issue which would eventually lead to the 1929 crash and much of which was out of his hands as Benjamin Strong and the other major central bank leaders were almost immune to political influence. The other members of this small club included the Bank of England director Montagu Norman, Bank of France director Emile Morceau, and Hjalmer Schacht of the Reichsbank. These men controlled world finance and tried to “sterilize” the reparations that France had insisted Germany pay for World War I. Strong was ill with tuberculosis and died in 1928, leaving the Federal Reserve in weak hands.

The Washington Naval Conference of 1923 was considered a success. It had major consequences as Japan was encouraged and England was damaged but Coolidge was a very determined disarmament advocate for fiscal reasons. He had little interest in foreign affairs although he was a mild supporter of the League of Nations and was not an isolationist as Hiram Johnson had been. Relations with Mexico had been poor since the 1911 Mexican revolution and Albert Fall had been expected to help with this but he chose to enrich himself instead. Ironically, the Teapot Dome scandal did eventually have some beneficial effects such as large capacity oil storage facilities in Pearl Harbor.

It also got a beautiful new library for my alma mater, the University of Southern California. Rufus von Kleinschmidt, president of the university, agreed to testify as a character witness for Harry Doheny, one of the principals in the Teapot Dome affair. Doheny donated a magnificent library that is still the center of the campus. It was donated in memory of his son, H L Doheny Jr and the date of his death is given as 1921. Many still probably assume that he was wounded in the war and died of his wounds but, in fact, he was shot by his mistress.

Coolidge’s first address to Congress as president took place on December 6, 1923. He presented a list of requests that continued Harding policies. Immigration was to be restricted for the first time. Railroads needed investment. Highways were to be funded although the states were expected to do much of this. He included other issues, such as civil service reforms and military and naval increases. Harding had been a great Navy president and Coolidge continued almost all his policies. He declined suggestions to cancel foreign debts, they would be canceled eventually anyway in the Depression. He differed a bit from Harding in his enthusiastic support for civil rights for “colored people” and advocated funding for black doctors and colleges. He opposed support for crop prices, which would become a major issue the rest of his presidency. His State of the Union address was the first to be broadcast to the American public. It was well received. The next night, at the annual Gridiron Dinner, he announced that he was a candidate for 1924.

His most important recommendation was for a reduction in the income tax rates, possibly one reason why Ronald Reagan was so fond of him. Wilson had raised income tax rates during the war to very high levels. The federal income tax had only been introduced in 1913. In 1914, only 360,000 tax payers had paid any tax at all. The Progressives who had been behind the constitutional amendment had seen it as a redistributionist measure and expected that only the rich would pay taxes. However, in 1917, Congress passed a surtax as a war measure that affected anyone with more than a $6,000 income. At $100,000 income, the tax was 25%. After the war, the surtax remained in place bringing in $1.3 billion in 1919 and over $1 billion in 1920, years of severe recession, if not depression. In 1920, the top bracket was 70% and while everyone talked about tax cuts, nobody seemed to do anything about it until Harding took office.

Coolidge had to convince a reluctant Congress about tax cuts. The Simmons-Longworth Bill, the best he could get, cut maximum surtax rates to 40% but raised the estate tax and added a gift tax. He wanted to return to pre-war rates but it was a hard fight. There is nothing new under the sun, least of all Congressional spending. The Coolidges worked on building friendships and entertained more than the Hardings had. One issue that was divisive was Prohibition. It was a Progressive initiative and Gifford Pinchot, a Progressive governor of Pennsylvania and passionate Prohibitionist complained that Coolidge was a weak supporter. The conventional wisdom has come down to us that Prohibition was a cause supported by blue nose Republicans. Nothing could be further from the truth. It was a Progressive cause. Pinchot supporters encouraged him to run against Coolidge in the 1924 primaries. They noted that brewery interests had supported Coolidge in Massachusetts. PInchot had already clashed with Coolidge when he asked him to intervene in a coal strike in Pennsylvania and Coolidge declined.

In October, 1923, the Tea Pot Dome scandal began to surface. Coolidge was under suspicion for a while as he had been present at many cabinet meetings where decisions were made. Eventually, he was shown to be clear of any involvement and his reputation as incorruptible kept him out of the scandal. Senator Thomas J Walsh of Montana, a Democrat and maverick, had been leading the investigation. Coolidge then took charge of the investigation, outflanking Walsh by appointing a special counsel. In fact, he appointed two, a Democrat and a Republican. This act took much of the partisan steam out of the scandal and it did not affect the 1924 election.

Harry Daugherty was the next Tea Pot Dome figure to come under scrutiny. He had been Harding’s campaign mastermind but he had no relationship with Coolidge. However, the austere Coolidge resisted efforts to dismiss Daugherty. He said “I will not remove the Attorney General, for two reasons. First, it is a sound rule that when the president dies in office, it is the duty of his successor for the remainder of that term to maintain the counselors and policies of the deceased president. Second, I ask you if there is any man in the cabinet for whom- were he still living- President Harding would more surely demand his day in court?

Tremendous pressure was brought to bear on Coolidge. One evening, February 18, 1924, William Borah, a powerful member of the Senate, was urging the president to request Daugherty’s resignation. As he talked, Daugherty walked into the room. Coolidge had arranged a mano a mano. The next day Burton K Wheeler (who was to incur my father’s bitter enmity by his isolationist antics in 1940), a freshman Democratic Senator from Montana, introduced a resolution calling for an investigation of Daugherty’s Justice Department. It was all based on innuendo. Recent investigation of the entire scandal has suggested that Daugherty, while appearances were not good, bore little responsibility for the crimes committed by some of his associates. In fact, some (including Coolidge’s biographer Robert Sobel) have concluded that the real target was Coolidge. He was well liked by the public but had little support within the GOP, especially the bosses.

Coolidge stood firm and many of the attacks on him by Democrats backfired. On February 29, the Democrats called upon him to release the tax records of Doheny, Fall and Sinclair. He refused noting this was prohibited by law. Slemp, his secretary, appeared before Congress as a witness and was questioned about telegrams he had seen. Nothing of consequence resulted. Burton K Wheeler then accused Daugherty of criminal activities. Daugherty retaliated with an accusation that Wheeler, a Democrat, was involved with the Industrial Workers of the World, the “Wobblies,” a radical socialist group. Eventually, the entire matter deteriorated into a series of accusations directed at each side. Daugherty refused to provide Justice Department records to the Senate committee and, eventually, this provided Coolidge with a justification to request his resignation and end the controversy.

For Daugherty’s replacement, Coolidge chose an Amherst alumnus (naturally), named Harlan Fisk Stone, former Dean of Columbia Law School and a distinguished judge. To replace Denby, Borah suggested Curtis Wilbur, an Annapolis graduate and Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court. Both were outstanding nominations and they were quickly confirmed. First, Coolidge had to ease Daugherty out and he asked Chief Justice Taft, with whom he had a close relationship, to bring Daugherty around to reality. Coolidge replied to Daugherty’s protests with ” I am not questioning your fairness or integrity. I am merely reciting the fact that you are placed in two positions; one is your personal interest, the other your office of attorney general, which may be in conflict. How can I satisfy a request for action in matters of this nature on the grounds that you, as attorney general, advise against it, when you are the individual against whom the inquiry is directed necessarily have a personal interest in it?” Daugherty protested but resigned the next day.

Harlan Stone was easily confirmed as Attorney General and the entire matter faded from public view, especially after Senator Wheeler was himself indicted on a bribery charge. He was eventually exonerated but the public lost interest in the committee and the scandal. The only people actually tried were Fall, Doheny and Sinclair. Later, after the matter had faded from the press, Wheeler and Walsh had occasion to meet with the president to plead for a road project in Montana. He listened to their presentation then commented dryly, “Well, I don’t want to see any scandal about it.” Wheeler told the story on himself

The entire matter had left Coolidge a popular president with the country but not in Washington. The politicians had not wanted him on the ticket in 1920 and they did not want him in 1924. His legislative agenda, some thirty recommended pieces of legislation, was defunct with only one item passed. That was a minor bill reorganizing the diplomatic service. The Soldiers’ Bonus Bill passed both houses of Congress and was vetoed by Coolidge as another would be by Roosevelt. It passed over his veto in the form of a paid up insurance plan which cost the government $2 billion. Coolidge signed the immigration bill with reluctance because it singled out Japanese immigrants for a total ban. This would have repercussions later in foreign policy with Japan. Newspapers commented on the record of Congress ignoring Coolidge’s agenda in legislation. However, the public was behind Coolidge. The 1924 election was coming quickly.

This is becoming too long for a single post and will be continued this weekend.

Michael,

Can you please put some of this post “blow the fold?”

There should not be more than 500 words or so above the gold, as a courtesy to other people posting on the blog.

This is a good series, Michael. Thank you for posting.

Wow great post. Looking forward to more.

As for the “below the fold” deal, I am a huge proponent of that, and take advantage of it after typically a paragraph or two. Most folks know by then if they want more or not.

Cool Cal would never be caught flying around the country patting himself on the back for a ‘gutsy call’ made possible by people his administration seeks to prosecute. Oh, how far we’ve ‘progressed.’

d(^_^)b

http://libertyatstake.blogspot.com/

“Because the Only Good Progressive is a Failed Progressive”

Jonathan has been helpful in getting the “below the fold” done.

This has been a great series. I’m looking forward to the weekend.