The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..

The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..

Radio had been pioneered in the early 1900s, but was initially restricted to wireless telegraphy for point-to-point or ship-to-shore use. Broadcasting has to wait for the introduction and improvement of vacuum tubes and development of a viable business model. The first US broadcasting station, KDKA in Pittsburgh, went on the air in November 1920 and reported the results of that year’s presidential election. By 1925, there were about 500 US radio stations, and nearly 20% of households owned a receiver. Good receivers were expensive, though: $119 for a loudspeaker model (headset-only versions were cheaper)…that’s about $2200 in our present money.

Broadcast stations all transmitted with vacuum tubes, however, there were still some earlier technologies (spark, arc, and alternator-based transmitters) in use for other applications.

One important broadcasting event of 1925 was the debut of WSM in Nashville and its most famous program, The Grand Old Opry; along with portable recording for the phonograph (discussed later), this would have a real impact on the national spread of music that had previously been regional or local.

The telephone was still far from universal–only about 35% of households had phones, and those that did used it mainly for local communication. (Telephone connections were often ‘party line’, so privacy could not be assumed) Transcontinental telephone service had been launched in 1911 (again, enabled by vacuum tube amplification) but was still very expensive. Rapid long-distance communication was usually conducted by telegraph. Morse code was still very much in use, although printing telegraphs had long been available and were handling a growing proportion of the traffic. One specialized form of printing telegraph was the stock ticker–these devices were shortly to get a real workout, in 1929.

Dial telephone technology had been developed and was expanding, but most calls were still completed manually by operators. There were 178,000 women working as operators in 1920 (men and boys had been tried, but did not work out well) and the number was still growing, reaching 342,000 by 1950. And those numbers count just the employees working in phone company central offices, not the switchboard operators in businesses and government offices.

Transoceanic telegraph cables had been in use since the 1860s, but undersea telephone cables were far from being a practical possibility. Still, a transatlantic telephone service would soon be available (launched in 1927), based on high-power long wave radio stations at each end…but not many could afford to use it.

Movies had reached extreme levels of popularity. I can’t find specific numbers for 1925, but by 1930, the weekly movie audience would reach 65 million. These were black & white films, and without sound–musical accompaniment was usually provided by local orchestras. Sound wasn’t too far away, though, the first mainstream sound film, The Jazz Singer, came out in 1927. The early sound films used a process called Vitaphone, which required synchronization of the sound on a phonograph record with the stream of images on film. It would be replaced by a process in which the soundtrack was recorded on the film itself.

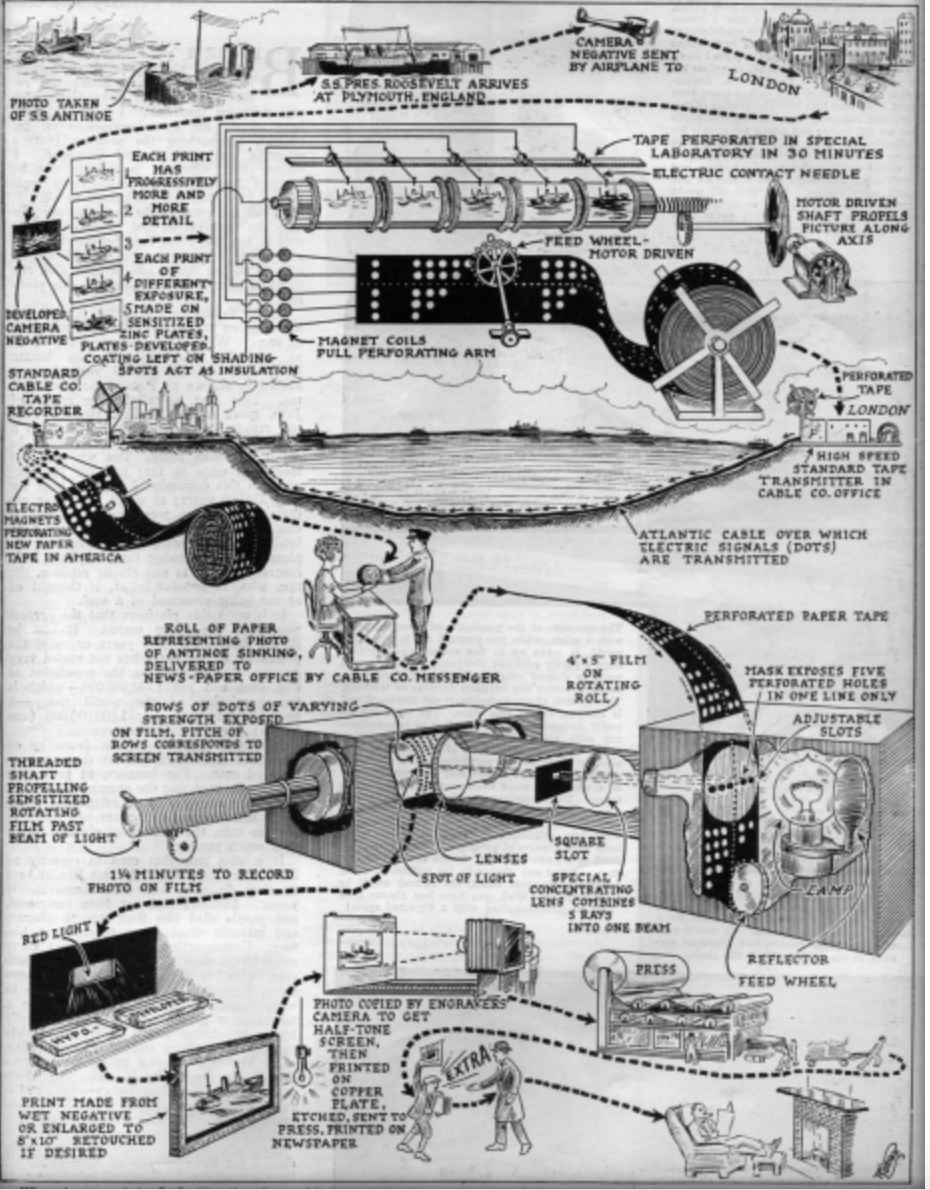

Newpapers were a huge deal in 1925. Their success was enabled by a convergence of technologies: the rotary printing press, the Linotype machine, photography and halftone printing, and the telegraph. (That line from the song The Easter Parade about “you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure” wouldn’t have made sense to people in 1925, since rotogravure printing wasn’t introduced until 1926.)

Just over the horizon (1927) was the teletypesetter,which allowed stories transmitted by telegraph to be entered directly into a Linotype machine for typesetting, without the necessity of being re-keyed…so a news item written by an Associated Press reporter in (say) New York City could be inserted into the copy for hundreds of newspapers around the country, almost untouched by human hands.

Books and magazines were increasingly popular–this phenomenon was driven more by expanded literacy than by any particular technological improvement, although mechanized binding and reduced paper costs (driven by improvements in chemical pulping processes) contributed to the growth of the book-publishing industry, while magazines benefited from highly-selective use of color. Grok says that in a mass-circulation weekly like the Saturday Evening Post you might see 1 full-color cover, 5-15 color ad pages (5-10% of total pages), occasional two-color accents (eg, blue headers) on 10-20% of editorial pages, and 80-90% black & white interior pages, and notes:

Where color appeared, it dazzled. A 1925 reader flipping to a Lucky Strike ad with a green pack and golden smoke in Collier’s (circulation ~1 million) felt the modernity of the Jazz Age. Publishers knew color sold—ads with it often doubled engagement, per early ad studies—and it became a status symbol. But for every color page, dozens stayed monochrome, balancing art with economics.

The Phonograph had been invented by Thomas Edison in 1877: for several decades, both recording and playback were via a direct mechanical process: for recording, sound vibrations were impressed on the cylinder or disk, and for playback, the process was reversed. Most home phonographs in 1925 would have been of this mechanical type, although some higher-end products had been introduced with electronic pickup and amplification. For recording, Western Electric introduced an electronics-based system in 1925. Some versions of this system were portable (although heavy and cumbersome)–previously, recording could only be done in studios, while with the new system, sound could be captured anywhere. Searching for new performers and new markets, record companies took the Western Electric system on the road to record music that had previously been heard only by local people: the Cash family being one example.

There’s a great documentary made in 2015, American Epic. An original 1925 recording machine was restored by engineer Nicholas Berg (the electronics runs off batteries and the recording lathe is powered by a descending weight) and the producers took the restored machine on an extended trip, introducing 1925 recording technology to some present-day performers and having them record their own renditions of music from the machine’s younger days. Highly recommended. The move website is here. The book that accompanies the program is subtitled The first time America heard itself.

Read more

The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..

The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..