Tea Partiers want to be left alone government kept from faith and speech, guns and books. Government restrained from taking property house or wallet. Anyone who thinks those beliefs don’t have legs isn’t getting my phone calls the tea party candidate’s supporters in the primary fill the answering machine and from my husband’s relatives fill our in-box. It has legs because this is who we are, or at least want to be: responsible adults, autonomous. Equivalence with the Occupiers misses core differences; Occupiers want what they fantasize the 1% have. We are human we covet. But Americans haven’t taken to OWS because we aren’t proud of our envy; we prefer grandeur to pettiness.

The Tea Party has roots – aware that restraint of power is difficult, but has a proud American history. Washington’s greatness lay not only in his victories but also his restraint he refused (as few have) to abuse his power restraint gained him respect, gave him another kind of power. Respect for flag and country characterizes the tea party; it is respect for a greatness defined by its restraint recognizing the limits of government when it bumps against man’s intrinsic rights.

Our system is designed (or was let’s hope is) to channel our desire for goods and power into productive action. A responsible individual sees money and respect derived from action. Goods gained by earned wealth and power by earned respect are not easily gained. If lust for power is too great, the respect necessary to achieve it will be withheld. And earned wealth is our goal to have tested our minds and muscles, stretched ourselves a bit, thought & invented. Our systems political and economic have built-in restraints. When we weaken those restraints (as surely the bail-outs did), we become less able to become who we can be.

America’s exceptionalism our outlier status is at root individualism. (See Lipset & Fischer) Liberty breeds it. We value community, faith, family, vocation. But our myths emphasize individual choice, liberty. Hyperbolic, hyperventilating, but not exactly wrong, Leslie Fiedler sees American cultural heroes as outsiders, pushing against the limits. Early modernists, we delight in heroes on the move, alienated perhaps, but mythic in their competence, their self-reliance. These twentieth century characters contrast with couples whose marriage and immersion in communities produce so many comedic conclusions. The Tea Partiers are part of the community, but each also relies on personal resources, personal strengths.

So, if this is us independent, resilient, but sometimes awfully high and lonesome do we see it in our culture? Well, yes. It was extreme in Roger Williams. As stubborn as heroic, as fervent as thoughtful, he defined a distinctive thread that runs throughout our culture. Most prefer John Winthrop, whose great lay-sermon “A Model of Christian Charity” emphasizes the “ligaments of love” that bind us. Not surprisingly, fewer settled Rhode Island. But Williams’ beliefs are bracing; Providence, with its houses in a straight line, each looking at its own horizon rather than facing one another, well, that is also our heritage. This spring, a good student observed that the Puritans stand in a circle contemplating the beauty of God’s grace; Transcendentalists stand in a circle looking outward, each contemplating his own horizon. He simplified; the Puritans were remarkably introspective and the Transcendentalists reinforced each other in their community. But he had a point. The introspection remained, but communal not so much. He was one of those who find the first quarter moving, but his irritation with the American romantics led him to a real truth.

We still read “Self-Reliance.” We prefer the rancher to the farmer, the hard boiled dick to the policeman, Shane‘s Alan Ladd to Van Heflin, Casablanca‘s Humphrey Bogart to Paul Henreid: they don’t get the girl; horizons beckon; they are the surveyors of the wilderness. Shane explains, they live by their own codes, could not be themselves (could not lose themselves) immersed in community & family. Shane says that with regret. But his position is firm. Competent and courageous, these hero’s codes are only imperfectly embodied in the laws of their world but firmly writ in their hearts. In more complex versions, deep sadness characterizes this alienation. But a sense of integrity, of the wholeness of the self, remains building the self is the hero’s responsibility. If film noir is America’s gift to twentieth century mythic alienation, our steps toward it began long ago. Our earliest writers are concerned with how man is rent from his God a rending that then rends us from one another.

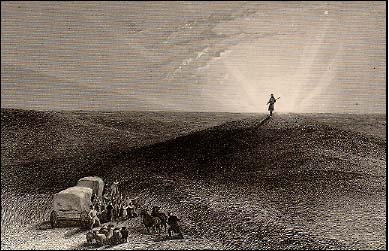

But if we saw the down side, we also saw the up. In the nineteenth century, we saw that rending is necessary for self-consciousness; it is the first step as each of us makes a separate self. In the first decades, this myth was perhaps best defined by James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851). The Spy is early espionage the epitome of the loner who for the good of the community takes its scorn. Natty Bumppo is an easier myth: he lives by his code; his maturity disciplined by nature which teaches him competence, proportionality, and humility. The nature that does that is sublime. Huge, beautiful, it beckons to the heroic in man. Cooper’s characters become dots on the horizon in a Cole painting. Natty Bumppo himself, larger than life with the sun setting behind him, reigns in an illustration for ;The Prairie, where, as a quite old man, he dies even then moving ahead of the encroaching “civilization.”

Cooper’s settings have a harsh grandeur, sublime and magnificent. He and his contemporary, Washington Irving (1783-1859), define American fiction’s early forms. Both use rural New York settings. Cooper sweeps us forward with his great narrative arcs, though his style may be cumbersome. Irving is urbane and witty, his practiced wit skewering characters, his style a model for schoolchildren. The two prepare the way for later, often more complex writers. Few characters, however, cast as grand a shadow as Leatherstocking.

It has roots I agree Ginny but there is a sizable percentage of Americans who want a govt check and not to work – but it is a minority I think – but a big minority.

Very apt – and a great many of the Tea Partiers that I know, they also have something of the same sense of history, and a grasp of our basic American character.

One of the major incentives for the tea party movement is a very rational and considered opinion that the statist vision of an all-encompassing government controlling vast areas of public and private life simply doesn’t work.

One of the major reasons that the opponents of the tea party accuse its members of rage and hatred and racism is that they are terrified of any in-depth discussion of governmental efficiency, competence, and productivity.

One of the major driving forces behind the tea party and its campaign against the expansive state is the simple realization by many capable and productive citizens that the so-called experts and technocrats who claim the right to run everything because of their alleged superior intelligience and training actually have no idea what they are doing, and the resulting economic and social disruptions they have created are irrefutable testimony as to their incompetence and cupidity.

The ordinary people of the US are the same people who operate and manage and deal with a 15+ trillion dollar economy with a global scope on a daily basis. They are far from the fools and stumblebums the elite tranzis snigger about at their cocktail parties.

The average citizen has looked at the mess we are in and made his or her judgement—all these experts don’t know what they’re doing, and need to be stopped, and curtailed sharply in the future, from pretending they can run everything and everybody.

The jury has deliberated carefully and announce its verdict—not competent by reason of arrogant stupidity and invincible ignorance.

Bring on the tar and feathers.