I. Departure

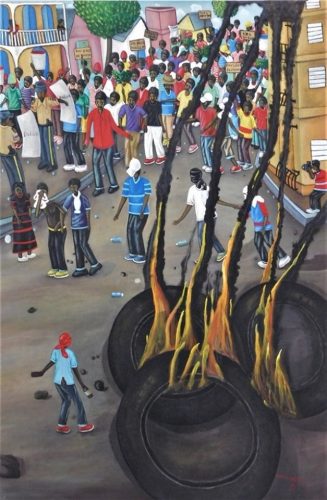

Our transportation to Aéroport International Toussaint Louverture was a decrepit Honda Civic with no working inside door handles, no exhaust system, and a barely functional starter. The guesthouse driver poured a liter of water into the radiator immediately before starting the engine so that it would not overheat, even though the drive was only 3 kilometers. Our luggage proved too big for the trunk, so most of the team’s belongings were wedged in beneath the open trunk lid, which was not secured by so much as a single bungee cord. Threading through the remnants of at least a dozen barricades on Avenue Gerard Téodart half an hour before sunrise, we high-centered on some rubble and dragged a sizable rock for several hundred meters before the driver backed the car up to dislodge it. After we made the turn onto Boulevard Toussaint Louverture, there were no more barricades, thanks to the proximity of a MINUSTAH logistics base and a Police Nationale d’Haïti station. There were pedestrians, of course—Port-au-Prince is very much a city that never sleeps—but not many, and few vehicles thanks to severely interrupted fuel deliveries, which had nearly stranded us altogether. One of the team members riding in the back seat later told me that the gas gauge was on “E.”

What is happening when a Third World country loses a key component of its energy supply, and what might be the lessons to learn for those apprehensive over a significant breakdown of logistics in the US?

II. Fuel Budgets, Culture, Population Density, and Their Consequences

I was in Haiti from 21-28 September, which stay included three nights in Port-au-Prince, four nights in Musac de La Vallée (hereafter “Mizak”), and a day trip to Jacmel, and thereby got a direct look at significant second-order consequences of Venezuelan collapse in the form of unavailability of subsidized fuel.

Haitian gasoline consumption is on the close order of 3 × 10ⵠbbl/mo; dividing by 30 yields a figure of 10ⴠbbl/day (half of daily imports of refined petroleum products). To two significant figures, 1 barrel = 160 L. Current population is just over 11 million. Daily per capita gasoline consumption is therefore ((1 × 10ⴠbbl/day) × 160 L/bbl) / 1.1 × 10ⷠpersons ≃ 0.15 L/person/day.

This may be taken as an upper limit; some online sources indicate that the real number may be as low as 0.05, which the corresponding US figure (~4.4) exceeds by nearly two orders of magnitude. For ease of calculation, I will assume the true figure to be 0.1 L/person/day. So if it’s that low, how much difference can it make in daily life for it to intermittently disappear altogether?

A “tap-tap” rated at 22 mpg (4.2 gal/100 mi) city and with 10 occupants is (22 miles × 1.6 km/mi) / (3.8 L/gal) ~ 10 km/L, and (~10 km/L) × 10 occupants ≃ 100 passenger-km / L = 0.01 L / passenger-km. This is probably an optimistic number, but again for ease of calculation, I will use it. Similarly, a moto with 2 riders rated at 75 mpg is (75 miles × 1.6 km/mi) / (3.8 L/gal) ≃ 30 km/L, and (≃30 km/L) × 2 occupants ≃ 60 passenger-km / L ~ 0.02 L / passenger-km.

Lessons from the above:

- The modal day for the modal Haitian is on foot. A single round trip of 10 kilometers can take an entire day’s fuel budget. An intercity trip, say Port-au-Prince to Petit-Goâve and back, can easily be a couple of weeks’ worth.

- The likely way around this constraint is for families to designate one member to run errands that involve traveling distances much greater than a typical walking radius (~2 km).

- As unpleasant as a crowded tap-tap can be, it’s much cheaper than a moto, which—given that the passenger is also paying for the driver—is ~4x higher to cover the same distance. This also explains motos with more than 1 passenger, a common sight.

Motos, incidentally, are much smaller than motorcycles in the US. The largest engine displacement I have ever directly observed on a two-wheeled vehicle in Haiti is 200cc. Nearly all are 150cc or lower. The smallest one I’ve ever ridden onshore was a 250cc Honda Nighthawk, and I owned an 1100cc (Yamaha XS Eleven) for several years in the first decade of the millennium.

Actual fuel prices vary considerably; the one data point I have is from a gas station on Route Nationale #2 somewhere around Gressier, where it was ((G224/L) / (93G/$)) × 3.8 L/gal ≃ $9.20/gal. This is $2.40/L, but rumor had prices ranging as high as $11/gal, which would be nearly $3/L. Haitian per capita GDP is $5/day, so 0.1 L/day can be ~6% of that for the average person. For comparison, the US figure (4.4 L/day at $2.67/gal = $0.70/L and per capita GDP of $~160/day) is less than 2%. So the (very approximate) US equivalent would be a tripling of motorized transportation costs for the average person. Historically, our actual gas price runups have been 50% or less, even in ’73-’74 and ’78-’80.

The analogous event, then, would be something at least twice as bad as the oil shocks of the ’70s happening to a country with, at best, 3% of our per capita wealth creation … and, per the Lewis Model, a “multi-active” culture which does not plan ahead in the North American “linear-active” manner.

Applying A = 4Ï€r ² shows that in a metro area with an aggregate population density of 17,000 persons/km ², the walking radius of 2 km mentioned above means that a pedestrian can routinely cover an area inhabited by over 200,000 people. Haiti’s capital is more densely populated than any American municipality or official subdivision thereof except Manhattan Island, and the commune of Port-au-Prince itself nearly equals Manhattan in density—with few wide streets and no buildings taller than about four stories.

Both its vehicular and pedestrian traffic density therefore appear stupefying to most Americans, myself certainly included, given that I live in a city with 1/30 the density and far more paved roads, streets, and traffic signals per capita (although, to be sure, many more cars per capita as well). An absence of heavy traffic in Port-au-Prince is a sure sign of trouble: the chikungunya pandemic in the summer of 2014, the desperate fuel shortages and unrest now.

So while the ability to physically access a six-digit number of one’s fellow citizens ordinarily means lots of amenities—and even in Haiti’s present circumstances, continues to fulfill the ancient function of cities as concentrations of information (p 503 ¶ 2)—hobbled motorized transport creates spot shortages of necessities literally overnight (again, in the absence of the sort of logistical planning we are used to). As I will explain below, this is much worse in the countryside.

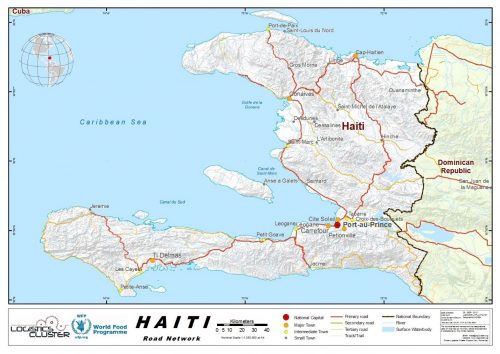

Besides port facilities, four main highways connect Port-au-Prince: Route Nationale #3 to the northeast, RN8 to the east, RN2 to the west, and RN1 to the northwest. All are two lanes, traverse significant topography, and are readily susceptible to blockade. This represents a severe logistical bottleneck for much of the country outside of the Port-au-Prince metro and south of the Massif du Nord, especially the Tiburon (southern) Peninsula.

Haiti’s population is estimated to be 11.3 million; subtracting the Port-au-Prince metro and the three northernmost départements (Nord-Ouest, Nord, and Nord-Est; assuming they can be supplied from Cap-Haïtien) leaves ~7.6 million. A bit of searching finds foodstuffs averaging 1500 kcal/kg and average daily caloric consumption in Haiti as 1850 kcal, which I will round down a bit to make the math easier; (1800 kcal/day) / (1500 kcal/kg) = 1.2 kg/day; (1.2 kg/person/day) × 7.6M people ≃ 9100T/day.

This amount could be transported on ~300 semi-trailers, 18,000 small pickup trucks, or some combination. A semi traveling 200 km would burn ~120L of fuel, and a small pickup would burn ~22L, so the total fuel budget to feed the southern two-thirds of Haiti from a road network effectively centered on Port-au-Prince is on the order of 4 × 10âµ L/day ~ 2,500 bbl ~ ¼ of all daily Haitian fuel consumption.

III. Adventures, Ground and Air

On Thursday 26 September, either Route Nationale #4, which goes north from Jacmel over the Chaîne de la Selle to Carrefour du Fort Léogâne, or RN2 somewhere between there and Port-au-Prince, were effectively cut by manifestasyons, which likely isolated most or all of four of Haiti’s ten départements (Grand’Anse, Nippes, Sud, and Sud-Est). I learned about this via the simple expedient of being directly affected by it.

Our team was picked up at Peace Inn in Mizak (18 °15’20” N, 72 °36’35” W) at 5:30 AM EDT that morning. Upon crossing the Pont Rivière Gauche about fifteen minutes later, our van driver spoke to the driver of another van returning to Jacmel and established that the road was blocked somewhere ahead.

Our objective was a guesthouse in a neighborhood called Village Thomas Théodat, only about a kilometer north of the east end of the airport. After coming in from the west on RN2, we expected the tricky spots to be around the Champs de Mars and—my best guess—the intersection of Delmas 33 and Route de Delmas. If all had gone well, we could have reached the guesthouse by 9 AM.

This approach having been obviated, our driver mentioned that a private plane could be chartered from the Jacmel airstrip (JAK) for $~100 per person. The team quickly agreed. We briefly discussed waiting until the next day—none of us were to fly out of PAP until Saturday—but I, for one, didn’t want to spend 24 hours wondering whether it would really work, so we proceeded to the airstrip … somehow getting around a burning barricade a few hundred meters west of the Rivière Grosseline. It was still dark. Somebody got up really early to get that one going; fortunately it was unmanned.

I had ridden past the Jacmel airstrip several times on the way to Plage Raymond-les-Bains and never seen any activity there, but that morning there was a 1977 Piper PA-32R-300 (N2296Q), parked outside the terminal, a more substantial building than I had realized. We actually went through security; our baggage was hand-searched by two guards who didn’t seem any worse at it than American TSA agents who do it about a thousand times more often. We paid cash, never showed ID, and one of the team wrote our names down on the flight plan. A Haitian woman was to have joined us as a fifth passenger but was left off the flight, reasons unknown, which I found annoying as it suggested favoritism for the grand blancs.

The flight was almost perfectly smooth; I had taken “less drowsy” Dramamine and felt no discomfort. Notwithstanding recent storms, it was mostly clear, the air seemed very stable, and the views were jaw-dropping. Our ground track roughly followed the roads we would have taken—north to the Léogâne Plain and east over Baie de Port-au-Prince, rather than straight northeast. It took, at most, half an hour.

Our arrival through General Aviation meant a short delay while our driver found us, nearly a kilometer east of the main terminal. On the way to the guesthouse, I saw the only UN vehicle I encountered on the entire trip, a plain white SUV pulling into the MINUSTAH logistics center. There were two PNH on a motorcycle on Avenue Gerard Téodart, where we passed the remnants of several barricades without incident. So we arrived somewhat earlier than originally planned.

Less than 48 hours later, after the brief but memorable predawn journey described at the beginning of this post, we were in the departure lounge at PAP. I am acutely aware that I was spared all but the briefest glimpses of the chaos which is disrupting the lives of millions of people in Haiti. Deye mon, gen mon.*

IV. Failure Modes and Responses

I am wont to quote Hollnagel, Woods, and Levenson on the components of resilience. I rate Haiti as follows …

- buffering capacity (absorb/adapt to disruption): medium-low; ordinary Haitians are able to employ uncomfortable but, thus far, survivable workarounds on timescales of a year or more

- flexibility vs stiffness (ability to restructure): low; Haiti has very little internal ability to significantly alter either its infrastructure or its vehicle/fuel options

- margin (distance to performance boundaries): low; living on 1850 kcal/day doesn’t leave a lot of reserve to draw on

- tolerance (graceful degradation vs collapse): medium-low; this seems to be a sort of punctuated equilibrium where functionality returns for a couple of days each week, so as noted above, they’ve managed to sputter along since sometime in 2018

All of these are—usually—much higher in the US, which is why we notice it so quickly when resilience is lacking, as in the gas lines of ’73 and ’79, or PG&E’s troubles in California now.

I have elsewhere criticized the flash-cut nature of disaster scenarios as favored by novelists—and preppers; everything “on” is turned “off,” by some kind of large, metaphorical, offstage knife-switch (the preferred diabolus ex machina being nuclear EMP). I encourage careful observation of real-world examples, in which only some things are turned off, and only intermittently. The people in Haiti in the most precarious position now are in the countryside—at the edge of the network, to use a 21st century expression. Fleeing to your hideout far from concentrations of population is not indicated, to put it mildly. What you want is the largest possible community, ideally one with excellent infrastructure connecting it to as much of the country as possible.

More broadly, beware single-root-cause analysis; all this is massively multifactorial. Familiarization with the Lewis Model, mentioned above, is helpful. That said, there seem to be two major factors at work in this situation, one internal and one external.

The internal factor is endemic low cooperation in politics, going back to the cultural founder effect of a slave-plantation colony successfully revolting and then not quite knowing what it wanted next. See Acemoglu and Robinson on extractive vs inclusive institutions. Haiti has no tradition of political compromise and has experienced at least 32 coups since its founding. At the moment it seems to be lurching toward its third delayed election in a row due to parliamentary gridlock and widespread distrust of its current president.

The good news is that the Haitian Revolution was won by the Haitians (and the good news for the US is that we immediately got the Louisiana Purchase out of it, and the first curbs on the slave trade shortly thereafter). Enabling the development of, eg, functional institutions is something else again.

The external factor is the collapse of Venezuela and its effect on the PetroCaribe fund, which was providing subsidized fuel. This unraveled last year, and much of the money associated with the program seems to have disappeared somewhere along the line in any case. Perhaps not coincidentally, the gourde’s value relative to the dollar has dropped from 41:1 to 93:1 over the eight and a half years I have been going to Haiti, and most of that decline has occurred since the spring of 2018.

The effects of the above are a good deal of public frustration, escalating to significant disruption in daily routines. As noted earlier, Haitian topography and limited road infrastructure combine with sociopolitical elements to practically guarantee that buffers become depleted, margins are always precarious, processes are not so much stiff as nonexistent (or hopelessly corrupt), and squeezes are always tight. A single relatively modest manifestasyon can close a chokepoint for an entire day.

At least some schools in Port-au-Prince were closed three days out of the week of 13 September (and probably every week since). There was much more traffic than usual on the roads on Sunday the 22nd when we rode up to Mizak, and I got the distinct impression that people were getting out to run errands while they could. Thankfully the rumor that RN2 had been physically cut near Léogâne was incorrect, but I observed remnants of roadblocks on both RN4 and the side road up La Vallée de Jacmel.

On days they are open, gas stations are swarmed by Haitians with jerrycans to buy as much fuel as possible—which often is limited to 5 gallons (Haiti uses a mixture of English and metric thanks to the 1915-34 US occupation), a familiar maximum to those of us old enough to have memories of the US economy in the ’70s. Gas stations are now guarded by TWO shotgun-carrying security people positioned to maintain overlapping fields of fire—I observed this at the (otherwise) pleasantly modern Sol gas station and convenience store/bakery in Léogâne.

Haitians are paying cash for purchases with the oldest, most tattered currency they have. The difference between it and relatively fresh bills is obvious; I suspect a sort of Gresham’s Law at work, combined with, or as an expression of, the natural (Haitian) tendency to hold better items in reserve.

If I may quote myself—

John Gilmore famously said that “the Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” The future adaptation of representative democracies will depend on our capability, as individuals, to interpret endemic institutional dysfunctionality as damage and route around it. In this regard, Haiti may be more advanced than the United States …

… even if only in the sense of being further along a harder road.

*various alliterative translations aside, the best colloquial English for this is probably “it’s just one damn thing after another”

Excellent post, Jay.

I wonder how much of this is a result of the pillaging, masked as disaster support, after the earthquake of 2010. My impression was that the Clintons,and maybe Bush, directed millions to Rodham, Hillary’s brother and other profiteers. What was the effect on the Dominican Republic, which shares the island and is also corrupt but seems far less dysfunctional.

At this point, it’s far more Maduro than Clinton.

So basically Baltimore without Baltimore’s access to white people?

Baltimore’s violent death rate is considerably higher, so we might speak of Baltimore’s lack of access to the positive elements of Haitian culture.

I suspect that the complexity and efficiency of our economic system will both work against it in the event of a major insult. True, we have some resilience due to that complexity as well, with different “pathways” available for supplying needs, but having little buffer (thanks to our efficiency) will make that less useful than we might hope.

Haiti has been a basket case since the revolution some 200 years ago. The underlying problem is the black population. Haiti’s problems exist in every predominately black country. They are genetic. There is no cure.

White rules helps, as witnessed by Rhodesia and South Africa.

See Acemoglu and Robinson for the counterexample of Botswana.

Coming soon to the glorious people’s republic of Amerikwa. Forward!

Re. Botswana: https://fee.org/articles/how-botswana-became-one-of-africas-wealthiest-nations/

Yikes. Several of the above comments really have no reason to be left up. I’d say overt racism unambiguously violates rule 1 of the comments policy.

As for the post, very interesting, and it’s completely horrifying to me that the nation isn’t scandalized by the northern California blackout situation. A reliable and dependable electricity grid really is a non-negotiable part of being a first world country. It doesn’t seem too long before NY, and perhaps other northeast blue states, are going to see similar problems. In NY, for instance, the governor and the Dems have done everything possible to choke off natural gas supplies (as well as close nuclear plants), and this summer the company that provides heating, electricity, etc. (National Grid) refused to hook up new houses since they couldn’t guarantee they would have enough gas to keep them supplied, leaving the idiot governor to fume that the utility has too much power and is playing politics with people’s energy, so they of course backed down and are making the hookups. But at some point soon at this rate, people are going to lose power and heat in January, and people will die, and the idiotic politicians who caused it all will not get any of the blame, and unfortunately too many out of staters will say “well, NYers deserve to get what they voted for”, neglecting the fact that upstate has absolutely zero political power, and people will continue to leave, and the Empire State will continue to crumble into dust.

Culture and race are intertwined. Historically black folks around the world have been associated with a culture that was/is relatively ineffective so Bob Sykes saying “genetic” isn’t accurate and Brian’s right, it’s racist. Bob Sykes could have said ” Haiti’s problems exist in every predominately black country. They are “inherent” (as opposed to genetic). There is no cure.” and been closer to the the truth of the matter IMHO.

.

But of course there is certainly “a cure”. Dark skinned people who are regular, functioning, citizens of the USA and elsewhere have demonstrated that there is a cure. In short, it’s adoption of the main thrusts of western civilization that are the cure.

tyouth19

@Anonymous,

Sykes may in fact be racist, but that does not belie the fact that it is accurate. Given the fact that relative performance of a society is tightly correlated to IQ, has a great deal of bearing on the ability of said individuals to build a civilization. Depending on which scale you use (have been several over the decades) somewhere around 80IQ or below the ability to maintain a viable society ceases.

See, https://brainstats.com/average-iq-by-country.html, then consider which areas of the globe are constantly in peril.

Dark skinned people who are regular, functioning, citizens of the USA and elsewhere have demonstrated that there is a cure. In short, it’s adoption of the main thrusts of western civilization that are the cure.

Yes. Theodore Dalrymple’s column is worth reading on the topic of failure in Africa.

The young black doctors who earned the same salary as we whites could not achieve the same standard of living for a very simple reason: they had an immense number of social obligations to fulfill. They were expected to provide for an ever expanding circle of family members (some of whom may have invested in their education) and people from their village, tribe, and province. An income that allowed a white to live like a lord because of a lack of such obligations scarcely raised a black above the level of his family. Mere equality of salary, therefore, was quite insufficient to procure for them the standard of living that they saw the whites had and that it was only human nature for them to desire””and believe themselves entitled to, on account of the superior talent that had allowed them to raise themselves above their fellows. In fact, a salary a thousand times as great would hardly have been sufficient to procure it: for their social obligations increased pari passu with their incomes.

That was Rhodesia before Zimbabwe. Now, of course, it is disaster.

Brian: “I’d say overt racism unambiguously violates rule 1 of the comments policy.”

That is very disappointing, Brian. Perhaps if a comment were overt racism, it would violate Rule 1. But it is far too easy for people to scream “Racism!” in order to shut down a discussion rather than to look seriously at the facts.

If I observed that the typical NBA team does not ‘look like America’, would that make me one of your racists? Or would it make me someone with eyes in my head?

Immigrants to several European countries are responsible for disproportionate shares of violent crime. If someone from Sweden or the UK makes that observation, does that make her a racist? The people who are going to have problems on Judgement Day are the self-satisfied well-insulated liberals who go around screaming “Racist!” every time someone mentions an inconvenient truth. The people screaming “Racists!” have blood on their hands — because they are shutting down discussion on important topics, which ensures that other innocent people will continue to be unnecessary victims of crime.

“Racism” today is mainly another one of the tools the liberal elite uses to divide and conquer us peons. Fight back! Don’t let those people control your thoughts.

From my experience I’ve found that Haitians are a wonderful people, but they have been cursed with extreme Bonapartism and Jacobinism, the duvaliera and aristide respectively, although the senior Duvalier, was one of those resistance leaders in the 30s and 40s,

Years ago, I went to school with the one who would be the longest serving prime minister in recent Haitian history, he had been the foreign minister, having worked for mickey martelly’s company, but he ran afoul of certain cronies of the regime at the time, and was dismissed,

Collectivist and single-root-cause analyses can, as seen above, quickly become overtly racist. Antidotes include individualism and explanatory granularity. Well, besides actually spending time in the environment(s) in question.

Lots of mostly pre-earthquake data in A Demographic Profile of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, including that Haitians had a labor force participation rate greater than the averages for both US natives and all immigrants combined.

The more recent Key facts about black immigrants in the U.S. presents a broadly positive picture regarding English proficiency and compliance with immigration law, but it is not specific to Haiti. My impression is that most Haitian immigrants quickly learn English (possibly excepting some of those in very large immigrant enclaves) but that well over the 15% foreign-born black average are “under the radar,” in part because of deliberately relaxed requirements in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake.

If you want to hear “Racism” against Haitians, I suggest you go visit their neighbor The Dominican Republic, and talk to the citizens. You will find numerous dark skinned Dominicans who -unprompted – will say the most derogatory things about them.

My experience in Haiti is that they are nice people, but completely unequipped to build a 1st world country. Its the “Talented Tenth” that provides the brains and leadership in most advanced countries, and in Haiti – that “tenth” has either emigrated to France or North America, or is uninterested in helping the rest of their countrymen pull out of poverty. All the “rah-rah open borders” types fail to understand that all those super-smart 3rd World professionals in the USA, are needed in the countries they came from.

I think that corruption and lack of properly enforced laws, which is just two ways to say the same thing, coupled with a lack of natural resources is more than enough to account for Haiti’s condition. No need for race to enter into it. As Venezuela shows, even abundant natural resources won’t do more than delay the inevitable once the corruption cripples that.

Everything that the article on Botswana cites is, unsurprisingly, absent in Haiti and has been throughout its history, absent U.S. Marines. Botswana, unfortunately, may be heading down the path of Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Calling the U.N. and Clinton Foundation earthquake relief a botch implies that it was ever intended to benefit the Haitians. It actually succeeded splendidly in enriching the “philanthropists” and bureaucrats. You wouldn’t expect Hillary to waste money on “those sorts of people”. The money spent in Haiti was the minimum needed to keep the grift going. The only efforts I ever heard being effective were the smaller scale, mostly religious inspired, ones.

“The only efforts I ever heard being effective were the smaller scale, mostly religious inspired, ones.” Every year my dentist and some of her assistants go to Haiti and work on people’s teeth for a week for free.

I have come to believe that the conceptually simpler and more broad-based the putative Haitian relief project, the better its chances of success (vaccination campaigns are the gold standard here). Also that the people who are going to make the greatest difference are not randos like me but the immigrants who keep a foot in both worlds, either by spending part of each year in Haiti and the US/Canada, or who eventually move back. A certain amount of forced repatriation from the US, obnoxious as it would be, might have interesting effects, though I would certainly prefer it be done through incentives rather than empowering FedGov; it is all too easy to imagine a future Administration using such powers to exile their opponents.

I think that Haiti is, and long has been, beyond redemption. Your part timers would either be co-opted by the corruptocrats or killed. The only outside entity that has ever managed to make any impression were the Marines, and that was fleeting and such interventions have since passed out of style.

If the aid fiasco had a bright side; it was that since so little money was spent in Haiti, the Haitian crooks were enriched far less than they expected.

There is no chance I see of an internal movement dislodging the the power structure, any such will be substituting one set of crooks for another. There is no outside power that is likely to see an advantage. Possibly, if Mexico succeeds in ejecting the cartels, they might try to take advantage of the situation. They would be ruthless enough.

The argument for race over culture as THE source of problems is belied by the facy of the third most prosperous nation group in the USA is Nigerian-Americans. They rank #3 in average income among national groupings… Mainly because they have one of the highest percentages of graduate degrees — Masters and higher — of any national grouping.

This seems improbable if race was actually central to the issue of black poverty.

“It’s the culture, stupid.”