Now that Mark Zuckerberg has admitted to caving to government pressure to censor Facebook users’ remarks about COVID policy and to suppress the story about Hunter Biden’s laptop and its incriminating emails, maybe it would be a good idea to revisit the policy of Facebook, YouTube and others to ban the mere mention of the name Eric Ciaramella, the CIA analyst rumored to be the whistleblower involved in Trump’s first impeachment. The New York Times profiled the whistleblower without naming names, and a number of journalists found one guy who fit the description. For whatever reasons, various platforms insist that if someone is rumored to be a government whistleblower, the person must receive absolutely no public mention under any circumstances or in any context whatsoever.

The whistleblower law prohibits the Intelligence Community Inspector General from disclosing the identity of a whistleblower, and it protects the whistleblower against workplace retaliation. It does not grant whistleblower anonymity – witnesses to the whistleblowing other than the ICIG are not prohibited from disclosing the person’s identity. The law certainly doesn’t prohibit anyone without firsthand knowledge from speculating on whistleblower identity. Various social media platforms and press outlets choose to censor EC’s name because they want to, not because they have to.

YouTube embraces this practice. It famously removed a video in which Rand Paul explains the significance of the question he wanted to put forth during the Senate impeachment proceedings, but which John Roberts would not allow. The question has no bearing on whistleblower identity, and everything to do with the origins of plans to impeach the President:

Are you aware that House intelligence committee staffer Shawn Misko had a close relationship with Eric Ciaramella while at the National Security Council together and are you aware and how do you respond to reports that Ciaramella and Misko may have worked together to plot impeaching the President before there were formal house impeachment proceedings?

Cited in the linked Federalist article, YouTube’s Ivy Choi said this of the censorship decision:

“Videos, comments, and other forms of content that mention the leaked whistleblower’s name violate YouTube’s Community Guidelines and will be removed from YouTube,” Choi said. “We’ve removed hundreds of videos and over ten thousand comments that contained the name. Video uploaders have the option to edit their videos and exclude the name and reupload.”

She confirms that the mere mention of Ciaramella’s name is prohibited, and she cites no rule that this prohibition enforces. I have searched YouTube’s community guidelines and cannot figure out what rule she claims to be enforcing.

Facebook’s community guidelines are more transparent than YouTube’s. They keep an online record of previous updates, but the change log for the Coordinating Harm and Promoting Crime section goes only as far back as November 30, 2019, and the first to apply to disclosing identities is in the November 18, 2020 update: “Do not post…Content revealing the identity of someone as a witness, informant, activist, or individuals whose identity or involvement in a legal case has been restricted from public disclosure.” If prior to that date a similar rule was filed in a different section, I can’t find it. The current policy prohibits “exposing the identity of [informants et. al.] and putting them at risk of harm [including]…Witnesses, informants , activists, detained persons or hostages.”

At the time of the 2019 impeachment proceedings, an unnamed Facebook spokesindividual confirmed that Facebook would purge “any and all mentions of the potential whistleblower’s name,” claiming that “Any mention of the potential whistleblower’s name violates our coordinating harm policy, which prohibits content ‘outing of witness, informant, or activist.'”

This claim misrepresents the letter of Facebook policy, as well as the English language. To expose something requires citing first-hand sources, which in this case are the instigator of and the direct witnesses to the filing of the whistleblower complaint. Facebook rules do not prohibit speculation about informant identity, nor do they prohibit the mere mention of an alleged informant without any reference to informant status (like the Rand Paul video banned by YouTube).

Except for the one example of individuals whose relevance to a legal proceeding is classified, the rule cannot be applied evenly. Public disclosure of hostage identity is sometimes authorized, as in the case of Hamas captives. The other situations describe persons who have and who have not been granted anonymity. Michael Cohen is a witness. Jacob Chansley’s status as a detained person was never a secret. Half the frickin’ Screen Actors Guild is composed of activists. Informants come in three varieties: identified citizen informant, informant from the criminal world known to law enforcement, and anonymous informant. An informant can be an NSA contractor leaking classified material. Or someone who publicly posts screenshots documenting that person’s conflict with an online entity – what I’m about to do.

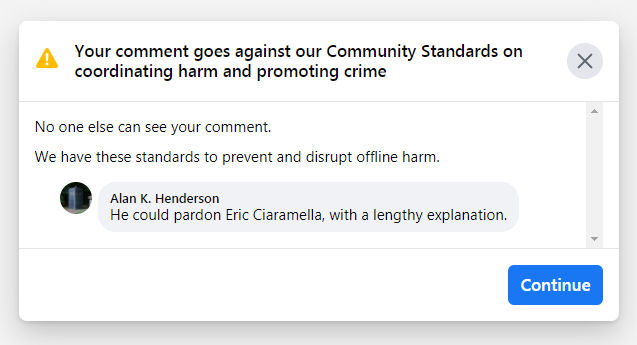

In social media when discussing a complex issue, I often try to cram everything I have to say into a single comment. On a few occasions I put forth the basic premise in one comment and work on the details to be posted later on in the anticipated reply chain. Such was the case in a comment to a Facebook post January 13, 2021.

You might be asking, “Pardon for what?” The whistleblower had failed to disclose in his report to the ICIG that he had contacted Adam Schiff’s staff about the matter prior to filing the report. Government record-keeping omissions do tend to be illegal. I felt that the nominal whistleblower was really a bit player in the impeachment fiasco, little more than a message boy. I based that opinion on the fact that the whistleblower report amounted to hearsay, and pundits had expressed the opinion that the language of the report had the appearance of having been written by a legal team rather than a single person. The pardon would demonstrate a willingness not to retaliate in response to the whistleblower’s direct role in the impeachment, and it would give Trump an excuse to speechify about the perfidy of much bigger fish like Schiff and Vindman.

Alas, I did not get a chance to elaborate on my pardon recommendation. Facebook sent a notification, which I decided to open in a separate tab.

When I saw this I considered two possibilities: a live operator was evil enough to misrepresent a recommendation for a pardon as an endorsement of harmful and/or criminal activity, or (more likely) a programmer was evil enough to create a bot that would automatically flag the mere mention of Ciaramella’s name as such. For at least a couple of years Facebook demonetized my account; as far as I can tell users do not have access to punishments history, so I don’t know when the ban was lifted. Now I really wish I could come up with ideas for monetizing it, just to stick a finger in the eye of Zuckerberg and the anonymous minion.

As stated earlier, Coordinating Harm and Promoting Crime is a section title in the guidelines. There is no objective means to determine that naming a non-anonymous witness, informant, activist, or detained person (citing examples form the current rules) presents a risk of harm greater than that posed by subjecting prominent individuals to negative press. P. Diddy might agree.

If Trump wins the November election that coincides with both Guy Fawkes Night and my 64th birthday, I still think he should issue that pardon – right before announcing a formal investigation of Obama administration officials’ involvement in the firing of Ukraine’s top prosecutor Viktor Shokin. RealClearInvestigations has a trove of White House emails relevant to the issue, some of which involve Ciaramella, who for two reasons would not be shielded from such an investigation. First, he’s now in the private sector. Second, as noted in the RCI article:

“None of the whistleblower protections apply to this particular situation,” said Jason Foster, former chief investigative counsel for the Senate Judiciary Committee and a whistleblower expert. He also noted that the Whistleblower Protection Act doesn’t shield whistleblowers from any other conduct they might have been involved in, including their own conduct. Nor does it give them a legal right to anonymity.

There is a related matter I want investigated. At least as late as June 9, 2015, the date of this letter from Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland to Viktor Shokin, our State Department was satisfied with Shokin’s law enforcement efforts. At some point this attitude changed, for reasons that have never been explained, and which should be documented somewhere in State Department emails. Time to start digging.

There were rumors that Facebook was set up under Zuckerberg with government support, for the explicit purpose of harvesting personal information on Americans. When Congress shut down the government’s Total Information Awareness project as a threat to civil liberties, the spooks merely resurrected it as Facebook.

If so, Zuckerberg may have felt he owed the government a favor or two.