A story about Maxine Waters [h/t Instapundit] and Barney Frank’s intervention on behalf of a minority owned bank on whose board Waters sat, has this little gem:

In January, Ms. Waters acknowledged she made a call to the Treasury on OneUnited’s behalf. The bank’s capital, which was heavily invested in shares of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, was all but wiped out with the federal takeover of the two mortgage giants, and the bank was seeking help from regulators. [emp added]

For leftists, OneUnited should represent the perfect bank. It’s small. It’s minority owned. The “socially responsible” Maxine Water’s invested in the bank and sat on its board. There’s no evidence it made predatory loans.

Yet, it failed.

It failed not due to any short-sighted greedy decisions that the bank’s management made but rather because the bank’s management, including board members like Waters, trusted that the mortgage-backed securities issued by the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fanny Mae and Freddie Mac were worth the paper they were written on.

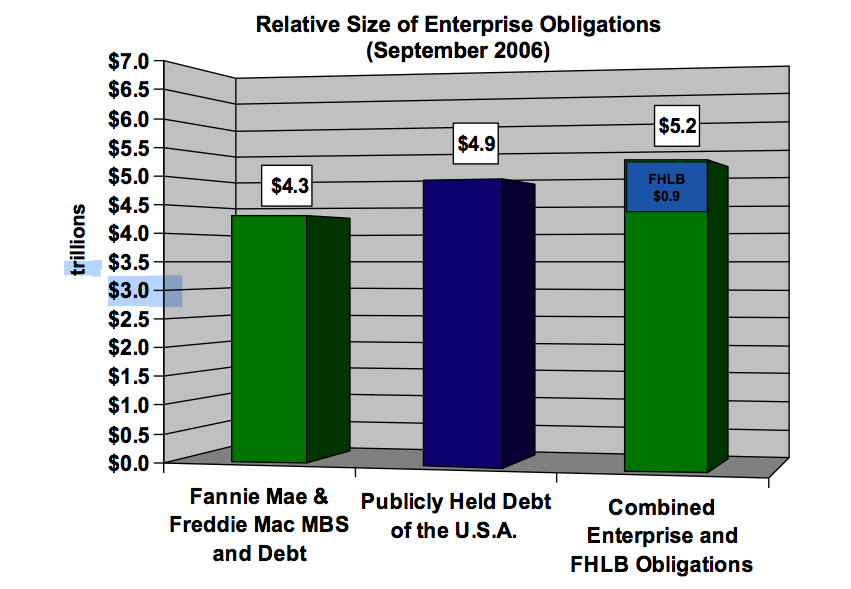

OneUnited is a microcosm of the entire financial collapse. Over the past 40 years the GSEs have piled up a vast store of toxic assets created by the attempt to get something for nothing by fooling the market about the risk of residential mortgages. Ratings firms gave the GSEs top ratings because of their implied government guarantee and oversight. Banks like OneUnited bought into the political myth and now they and everyone else are paying for it.

Leftists need to explain why we shouldn’t regard the failure of OneUnited and other institutions as the results of government action. They won’t, of course.