Today, the trial begins to determine if Detroit can enter chapter 9 bankruptcy. I have been trying to read a lot about what this means for the muni bond markets. As of right now, not much. But in the future, possibly a lot.

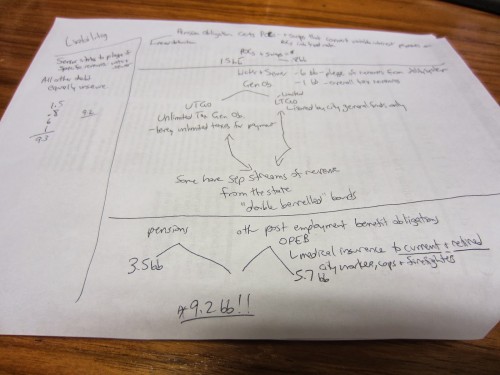

Here is a great piece on the subject and one that I will refer to through this post. It is written by the Chicago Fed, and explains what is going on, and how the Emergency Manager, Kevyn Orr, is going about trying to right the ship. The document is short, but somewhat dense. I had to read it three times and making some notes helped me understand it better.

After making this diagram, I joked to myself that this is probably a better flow chart understanding of the City of Detroit’s debt than any sort of financial documents the city of Detroit had prior to the EM taking over. But I digress.

After the issue of letting Detroit go Chapter 9 is resolved (I guess I don’t really see any other option) there are several interesting issues that may affect the muni bond market moving forward.

The debt looks like this, in simplified form:

Water and sewer debt – $6bb

General Obligation debt (limited tax backed and unlimited tax backed) – $1bb

Pension Obligation Certificates and associated swaps – $2.3bb

Pensions – $3.5bb

Other Post Employment Benefit Obligations – $5.7bb

First, Orr has decided that the only things that he will be treating as secured debt will be the water and sewer system bonds (backed by a pledge of revenues from the utility system) and the “double barreled” UTGO (unlimited tax general obligation) and LTGO (limited tax general obligation) bonds. Double barreled means that these certain bonds have separate income streams derived from the State of Michigan. This is significant because no General Obligation bond in the muni universe in any Chapter 9 filing has ever been impaired (with the exception of the disastrous Jefferson County, Alabama filing in 2011). Basically, Orr is offering ten cents on the dollar to EVERYONE that is not secured. This includes pensions, OPEB (other post employment benefit) plans, pension obligation certificates, swaps, and all the rest. In the middle of this, the fact that Orr treated the UTGO debt (which can be funded by unlimited property tax levies) just like all of the other debt is a first. This will also be settled in court, and will affect the perception of a lot of other cities’ GO debt as relates to the backing by property tax levies.

The next Big Deal to the muni bond universe is that there is a conflict between state and federal law as to if Orr can pound down the pensions and OPEBs. Law in the State of Michigan says he can’t but federal law has no issue with it. There is no law on record that addresses this and I am sure it will be a bitter battle to the end. If there is some sort of sweeping Tenth Amendment ruling that says that you can’t touch the pensions, this will affect the debt of a LOT of large cities that have similar state laws in place, such as Chicago, LA and others that have giant unfunded pension obligations. But to me, winning this in court is one thing for the pensions, actually getting the money out of the city of Detroit, that has none, is quite another. I am sure that they would at that time try to get preferred secure status over the utility bonds, but I don’t think that will really happen.

So far, the markets have just shrugged their shoulders at this whole affair, with the small exception of punishing the bonds slightly from places in the State of Michigan. I am sure that as this disaster winds its way through the courts, that this may change. Being an investor in the muni market, I will be keeping a close eye on how this plays out, as well as the soon to be crisis in Puerto Rico.

Cross posted at LITGM.