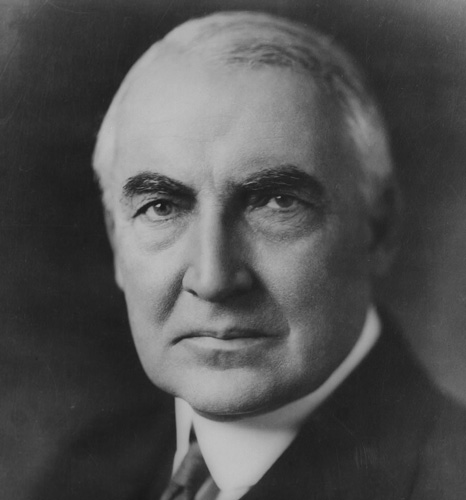

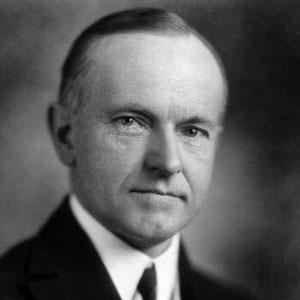

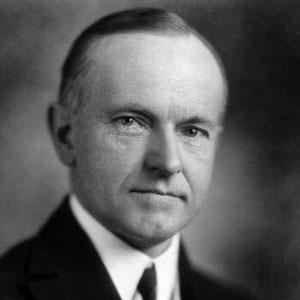

Calvin Coolidge is one of our least understood, and certainly least appreciated presidents. Here is what the hip (for the times) writers had to say.

Apart from that, he did little, and believed that the surging stock market vindicated his minimalist approach. He showed as little concern for the idea that the boom might be unsustainable as he did for the fact that, during his presidency, membership of the Ku Klux Klan exceeded 4 million. Instead, he developed, and encouraged a reputation for being a man of few words. Commentators approved. “This active inactivity suits the mood and certain of the needs of the country admirably,” wrote Walter Lippmann in 1926. No one imagined the economic catastrophe that lay ahead.

I have just read Coolidge’s autobiography and have another thought. First, all the clever quips about him show no understanding at all of his nature and experience. Second, would the “economic catastrophe that lay ahead” have occurred if he had chosen to run for another term ? Was the boom “unsustainable” ?

There is a thread of self hatred in all the discussion of the “Roaring 20s” and The Depression. We deserved the Depression, as best I can tell from the writings of the Roosevelt supporters after 1932.

Here is Coolidge in some of his own words. First, everyone should read this book to get an understanding of what America was like before the Welfare State. John Calvin Coolidge was raised by a father who taught him industry and thrift. His grandfather, Calvin Galusha Coolidge, died when his grandson was six years old. Here is the impression he made on his grandson.

“He was a spare man over 6 feet tall, of a nature that caused people to confide in him, and of a character which made him a constant choice for public office.”

“He and my grandmother brought up as their own children, the boy and girl of his only sister, whose parents died when they were less than two years old. He made them no charge, but managed their inheritance and turned it all over to them with the income, besides giving the boy $800 of his own money when he was eighteen years old, the same as he did my father.”

“In his mind, the only real respectable way to get a living was from tilling the soil. He therefore did not exactly approve having his son go into trade.

In order to tie me to the land, in his last sickness he executed a deed to me for life of forty acres, called the Lime Kiln lot, on the west part of his farm, with the remainder to my lineal descendants, thinking that, as I could not sell it, and my creditors could not get it, it would be necessary for me to cultivate it.”

Coolidge’s father kept a store and was elected to the state legislature. He chose the law for his son although it was very hard for him when his son left for Massachusetts to follow his desires. The account of Calvin’s boyhood is one of hard work but simple pleasure. He drove a team of oxen for plowing when he was 12 years old. Anyone who assumed airs were held in contempt. If the hired girl or man needed to go to town with the family, Calvin surrendered his seat in the wagon. His mother was an invalid although a strong personality. She died at 39 when he was a boy.

At the age of 13, he was sent to an Academy to further his schooling and prepare him for college. Both boys and girls attended and several of his family were graduates. He worked part time in a cab shop in the town where the Black River Academy lay. Vacations were from May to September to allow time for farm work. His father paid for his school expenses but any extra money he earned was deposited in a bank for him by his father. The principal and his assistant both lived to see Coolidge President.

In March of his senior year, his younger sister died of appendicitis. This was 1890 and knowledge of appendicitis was very recent. He carried this heartbreak with the discretion common for the time. After graduation, he moved on to Amherst College. His education was delayed a year as he became ill and had to spend time recovering; time he spent painting the interior of his father’s store. In the fall of 1891, he finally began at Amherst. His father remarried the year he began college and he was very fond of his stepmother, a school teacher.

In college, Coolidge excelled in mathematics, including calculus. He was not so strong in languages. His studies in History and Philosophy were also favorites. His grades improved with time and he graduated cum laude. From there, he entered into the study of law. He served as clerk for a firm whose partners he greatly respected. He dryly comments on the two methods of learning the law, by schooling and by experience. He prefers the latter and writes, “I think counsels are mistaken in the facts of their case about as often as they are mistaken in the law.” He also comments, “It is one thing to know how to get admitted to the bar but quite another to know how to practice law. Those who attend a law school know how to pass examinations, while those who study in an office know how to apply their knowledge to actual practice.”

He lived within the frugal limits of the funds his father provided for his upkeep, $30 per month. This left little for “unnecessary pleasantries of life.” In June of 1897, he felt adequately prepared for the bar exam and took it, passing as of July 4. 1897. He then entered the practice of general law. Since he had completed his preparation in less time than he had expected, he remained in the same law office for seven months after being admitted to the bar before he settled in an office in Northhampton. Here, he was to remain for 21 years until elected Governor of Massachusetts. His rent for his office was $200 per year.

He became involved in local politics, natural for a lawyer, and was elected to the city council, then became City Solicitor, which came with a salary of $600 per year. He held this office until 1902. In 1903, he was appointed Clerk of the Courts for Hampshire County by the Supreme Judicial Court. He considered this the highest honor he received as a lawyer. In 1904, he met Grace Goodhue who had graduated from college and came to the Clarke School for the Deaf to teach.

They were married in October of 1905. In 1906, they rented the home, half of a two family house, they were to have for 31 years. Their first child was born in September 1906. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives and served two terms, after which he declined renomination, something of a tradition in Massachusetts politics. Their second son was born and Calvin decided to devote all his time to his law practice. In 1910, he was elected Mayor of Northhampton. This was a local office and would not interfere with his law practice. In 1911, he was elected to the Massachusetts state Senate. He was re-elected in 1912 and became something of a force, interested in the western part of the state and its issues, especially transportation which at the time meant trolleys and railroads. In 1914, a bad year for Republicans, he became President of the Senate with the support of most of the Democrats as well as his own party.

The World War began the following summer. The Republicans were able to unite and became the legislative majority in the following election. The Governor was a Democrat but he and Coolidge cooperated well. Some of Coolidge’s later philosophy began here as he shows pride in reducing the volume of legislation and regulations in each year he served as President of the Senate, an office second only to the Governor. After the 1915 legislative session, he had intended to return to his law practice but found that he was being widely supported for Lieutenant Governor. He dryly comments that he was widely considered a liberal but even the businessmen came to him to offer support. As a result, he offered his name for the office but did not campaign.

He was elected Lieutenant Governor in 1915 by 75,000 to 50,000. He had spent the election season campaigning for the candidate for Governor, Samuel McCall. Since the office did not include presiding over the state Senate, Coolidge thought he might have time for his law practice but this was not to be and he took in an associate who, in time, took over the law practice. He mentions that the public expects Chief Executives in all levels of government to conduct themselves as an “entertainment bureau.” For this reason, he spent much time speaking on behalf of the Governor.

In 1917, the US entered the war and the Governor, who wished to become a US Senator, suggested that Coolidge announce for Governor in 1918. He was elected and, shortly after the election, the Armistice was signed, ending the War.

I will continue this in the next post. I think Coolidge will become a more important historical figure as we see how Barack Obama is duplicating the pattern of Hoover/Roosevelt in turning a severe recession into a depression. Had Coolidge been president in 1929-30, history might be very different. In the next post, I will go more into his political philosophy as VP and President.