Walter McDougall introduces us to young Alexis de Tocqueville in his book Throes of Democracy:

As late as 1997 a historian with some pretensions to veracity wrote (albeit tongue in cheek) that “complete objectivity about America is a characteristic only of God and Alexis de Tocqueville”. In truth, the young Frenchman’s methods were highly subjective. He was an aristocrat whose parents narrowly escaped the guillotine during the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution. So he came to America inclined to believe that government in the hands of the envious masses was far more dangerous than rule by disinterested aristocrats. Tocqueville was raised a Catholic, but exposure to Enlightenment philosophy hobbled his faith: “I believe, but I cannot practice”. So he came to America with little appreciation of what made religious people tick, especially Protestants of British stock. His classical education and training for a French legal career biased his mind toward deduction rather than empirical, historical thought. So he came to America with little sense of the profound experience that inspired the thirteen colonies to found the United States.

Tocqueville traveled for other motives:

Most tellingly, Tocqueville’s motive was didactic. He meant to argue that democracy either did not work in America or else could not be made to work back in France. What prompted his journey in the first place was the French Revolution of 1830 that overthrew the last Bourbon king and installed the “bourgeois monarchy” of Louis-Philippe. Its motto was juste milieu, meaning government prudently balanced between royal and popular sovereignty. But it was born of mob violence and its empowerment of the French middle class was bound to provoke demands for representation from the lower classes.

Tocqueville’s worldview bred some observational quirks:

Tocqueville revealed another damaging trait, which was to turn the opinions of others or his own first impressions into postulates. He took the New York chandler Peter Schermerhorn at his word when Schermerhorn insisted that there was no rancorous party spirit in America, that the Union was in no danger of dissolution, and that the “greatest blot on the national character was the avidity to get riche and to do it by any means whatever”. Tocqueville’s diary and letters reveal a plethora of instant judgments. Upon meeting the governor of New York in a humble boarding house, he concluded, “the greatest equality seems to reign, even among those who occupy very different positions in society.” Upon hearing Americans boast over their “very copious’ suppers he decided, “These people seem to me stinking with national conceit, it pierces through all their courtesy”. After one Sunday in Manhattan, he wrote, “Taken together,” the Americans “seem a religious people”. After one stroll down Broadway he agreed with [his friend and traveling companion Gustave de] Beaumont that fine arts in America “are still in their infancy”. After one conversation he decided, “Political passions here are only on the surface. The profound passion…is the acquisition of riches; and there are a thousand ways of acquiring them,” many of which involved “cupidity, fraud, and bad faith”. All those judgements were rendered during Tocqueville’s first week in the country even though, he confessed in a letter, his English was still laughably poor.

Tocqueville made curious scheduling decisions:

Tocqueville and Beaumont spend only forty-one weeks on American soil. Their inspections of Sing Sing and other prisons consumed eight weeks. Beaumont’s desire to study Indians around the Great Lakes cost five more weeks. A sentimental journey to French Quebec lasted ten days. Nor did they use the remaining six months wisely: they devoted to the entire South just one month.

Tocqueville continued his streak of “snap judgements”:

He decided that Philadelphians “knew only arithmetic” because of their grid of numbered streets, and that their women “practice and unrestrained coquetry” even though “tout de monde agrees in acknowledging that they stop there.” A Quaker merchant who had lived in New Orleans told him that northerners were active, intelligent, cold, and calculating, whereas southerners were open and lively but inclined to a hauteur and laziness. This primed Tocqueville to admire New England and to sense something “disorderly, revolutionary, passionate” about the South. On the shores of Lake Huron an old Catholic priest dismissed America’s 450-odd Protestant sects as rienists (“nothingarians“), wherefore Tocqueville deduced that all Americans must someday gravitate to natural religion or Catholicism! In Cincinnati he was told Ohio thrived while Kentucky languished on account of slavery in the latter. Accordingly,Tocqueville failed to notice the fantastic wealth of planters and merchants as he raced through the South on steamboats and stagecoaches.

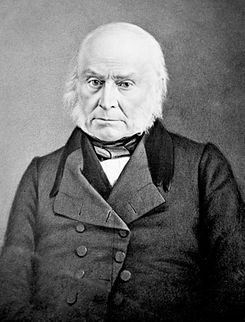

In Washington City, the former president John Quincy Adams explained that whereas New England was founded “by a race of very enlightened and profoundly religious men,” the new western states were “populated by all the adventurers to be found in the Union, people who for the moste part were without principles or morality” or “who knew only the passion to get rich”. Had Tocqueville visited Saint Louis and talked with Senator Thomas Hart Benton, perhaps he would xanaxcost have realized how quickly the West was replicating the civilization beloved by Adams. He even squandered his entrée in the federal city by engaging in small talk with President Jackson and evening frivolities with his cabinet. In any event, Tocqueville though the rustic capital a sorry excuse for America’s Paris, and couldn’t wait to board ship for home. He admitted having spent less than half the time needed to get a true picture of the United States. “Yet I hope I have not wasted my time.”

McDougall argues that Tocqueville missed a lot about America:

Insofar as De la Democratie en Amerique made him famous he had not wasted his time. But the volumes were neither systematic nor thorough. Tocqueville failed to cover the country in terms of geography; never set foot in a college or factory; and met no authors, artists, or scientists. He studied no canals and failed to grasp how important government-private partnerships were in constructing them. He inspected no miliary or naval facilities, and witnessed no revivals or camp meetings. He heard complaints about Jackson, but missed the new two-party system then in gestation. He suspected the potential of railroads, but did not imagine the transport, energy, and industrial revolutions they would spark. It could even be said that the society he tried to describe in Democracy in America ceased to exist before the decade was out.

Not that the young Frenchman’s work was without insight:

Tocqueville deserves renown. He helped to pioneer sociology and posed questions of timeless relevance. What institutions, laws, and customs make a democracy? Are democratic ideals universal, and if so must democratic forms vary across nations and cultures? What social conventions and popular habits buttress or threaten democracy? Moreover, he got some things right. Although irony was not in his nature, he suspected democracy in America was a great truth maintained by a delicate balance of fictions. A brilliant young lawyer in Cincinnati gave him the clue. “We have carried ‘Democracy’ to its last limits,” the man said. “The right of voting is universal. Thence result, especially in our towns, some very bad elections.” The unworthy candidates won “by mingling with the populace, by base flattery, by drinking with it,” whereas distinguished men simply “can’t struggle struggle against the flood of public opinion.” Thus did the future chief justice Salmon P. Chase encourage Tocqueville to conclude that “the ablest men in the United States are rarely placed at the head of affairs”.

Yet, even with a scaffolding of “fiction”, democracy in America had important supports:

Last but not least, democracy in America was sustained by a breathtaking conformity imposed by public opinion shaped in turn by religion. Tocqueville learned that last point from a doctor in Baltimore. Don’t be misled, the doctor said, by separation of church and state and the seeming indifference to doctrine prevailing among Protestants. The great majority of Americans were fervent believers and quick to ostracize unbelief. Such social pressure mus create many hypocrites, Tocqueville replied. Yes, said the doctor, but “it prevents people’s speaking of it. Public opinion accomplishes with us what the Inquisition was never able to do.” If American men (not to say women) desired success in society, matrimony, business, or politics, they learned “to keep their mouths shut” about religious doubts. Tocqueville did not grimace; he marveled. So their secret was this. Americans were a people “seeking with almost equal eagerness material wealth and moral satisfaction; heaven in the world beyond, and well-being and liberty in this one.” They established a religious tolerance to which even Catholics conformed. But a dominant Protestant ethic regulated domestic life, especially through the influence of women, forging a public consensus that in turn regulated the state. To be sure, sects proliferated. But all conflated civil and religious liberty and all preached the same moral code. “Thus while the law permits the Americans to do what they please, religion prevents them from conceiving, and forbids them to commit, what is rash or unjust.”

Now Tocqueville knew why missionaries from New England were so anxious to proselytize the West. Since the liberty and equality Americans cherished were derived from religion, the future of their democracy hinged on saving the frontier from heathenism. “Despotism may govern without faith,” he wrote, “but liberty cannot…How is it possible that society should escape destruction if the moral tie is not strengthened in proportion as the political tie is relaxed? And what can be done with a people who are their own masters if they are not submissive to the Diety?” Evidently, the American answer was to help them believe, and if they still could not believe make them fake it. Thus were the spirits of religion and liberty, so often at war in Europe, “intimately united” in America. The separation of church and state empowered Protestant public opinion to make civil society a sort of church.

“The American,” Tocqueville quipped, “is the Englishman left to himself.”

Originally posted on the Committee of Public Safety.

“How is it possible that society should escape destruction if the moral tie is not strengthened in proportion as the political tie is relaxed?”

Good post Fouche. The above quote encompasses much of our current social questions and problems, doesn’t it? One might put it another way: “when the people cannot rule themselves, the will be ruled” (quotes mine).

arrrgh! that last should read “they will be ruled”.

Another Frenchman who visited the U.S. in roughly the same time period was Michael Chevalier. He was an engineer, here on an official government mission to check out the canals, railroads, etc, but he was also an astute social observer. The title of the book is “Society, Manners, and Politics in the United States.” I’ll try to pull some extracts if I get time.

Interesting and valuable post. I received the Liberty Fund four volume French/English version of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America; and while I read a version of DOA twenty years ago, this post combined w/the gift encouraged me to give it another look. Many thanks!

I read Democracy in America with a book group about ten years ago. We broke the book into ten chunks and met once a month and drilled down. A great experience. Despite the difficulties noted, Tocqueville had a good gut, and got a lot of it right.

David, yet another interesting book suggestion. Society, Manners, and Politics in the United States by Michael Chevalier looks promising.

I have started this book, but I strongly recommend reading Freedom just around the corner first. It is the first in a three volume general history of the US that is outstanding for many reasons.