Through an English friend in the Chinese service, Ward obtained an introduction to Wu, the Taotoi of Shanghai, and to a millionaire merchant and mandarin named Tah Kee. The plan he proposed was as simple as it was daring. He offered to recruit a foreign legion, with which he would defend Shanghai, and at the same time attack such of the Taiping strongholds as were within striking distance, stipulating that for every city captured he was to receive seventy-five thousand dollars in gold, that his men were to have the first day’s looting, and that each place taken should immediately be garrisoned by imperial troops, leaving his own force free for further operations. Wu on behalf of the government, and Tah Kee as the representative of the Shanghai merchants, promptly agreed to this proposal, and signed the contract. They had, indeed, everything to gain and nothing to lose. It was also arranged that Tah Kee should at the outset furnish the arms, ammunition, clothing, and commissary supplies necessary to equip the legion. These preliminaries once settled, Ward wasted no time in recruiting his force, for every day was bringing the Taipings nearer. A number of brave and experienced officers, for the most part soldiers of fortune like himself, hastened to offer him their services, General Edward Forester, an American, being appointed second in command. The rank and file of the legion was recruited from the scum and offscourings of the East, Malay pirates, Burmese dacoits, Tartar brigands, and desperadoes, adventurers, and fugitives from justice from every corner of the farther East being attracted by the high rate of pay, which in view of the hazardous nature of the service, was fixed at one hundred dollars a month for enlisted men, and proportionately more for officers. The non-commissioned officers, who were counted upon to stiffen the ranks of the Orientals, were for the most part veterans of continental armies, and could be relied upon to fight as long as stock and barrel held together. The officers carried swords and Colt’s revolvers, the latter proving terribly effective in the hand-to-hand fighting which Ward made the rule; while the men were armed with Sharp’s repeating carbines and the vicious Malay kris. Everything considered, I doubt if a more formidable aggregation of ruffians ever took the field. Ward placed his men under a discipline which made that of the German army appear like a kindergarten; taught them the tactics he had learned under Garibaldi, Walker, and Juarez; and finally, when they were as keen as razors and as tough as rawhide, he entered them in battle on a most astonished foe.

From Gentlemen Rovers by E. Alexander Powell (1913), chapter entitled “Cities Taken by Contract” about Frederick Townsend Ward and the Ever Victorious Army during the Taiping Rebellion. After Ward’s death, the Ever Victorious Army was led on to victory by Charles “Chinese” Gordon. (The title of Powell’s book is based on the poem The Lost Legion by Rudyard Kipling.) See also The “Ever Victorious Army”: A History of the Chinese Campaign under Lt.-Col. C.G. Gordon, C.B., R.E., and of the Suppression of the Tai-Ping Rebellion by Andrew Wilson (1868).

UPDATE: Reading the Wilson book, I found this excellent paragraph, about the death of the Emperor, who had suffered both the Taiping rebellion as well as foreign invasion, culminating in the destruction of the Summer Palace, and unremitting disaster throughout his reign:

About this time some events occurred at Peking which had a not unimportant bearing on the future of China and of Tai-pingdom. On the 21st August the Emperor Hien-fung died at the Jehol, his hunting-seat in Tartary, in the 26th year of his age and the 11th of his reign. Unequal to the difficulties of a transition period, he had, like many other rulers similarly placed, sought consolation in sensual indulgences, and had allowed himself to be led by unworthy favourites. At last, as the decree announcing his death stated, “his malady attacked him with increasing violence, bringing him to the last extremity, and on the 17th day of the moon he sped upwards upon the dragon to be a guest on high. We tore the earth and cried to heaven, yet reached we not to him with our hands or voices.” When the mortal shell of this frail and unfortunate monarch was laid in its ” cedar palace,” his spirit ascending on the dragon would have many strange things to tell to the older Emperors of his line. He would have to speak of trouble, rebellion, and change through all the years of his reign, over all the vast plains of the Celestial Empire, from the guttural voiced tribes of Mongolia and the blue-capped Mohammedans of Shensi, down to the innumerable pirates of Kwangtung; he might complain that, east and west, north and south, his people had been disobedient and rebellious; the administration of his empire had been set at defiance, and his sacred decrees had been imperfectly carried out by weak and corrupt viceroys, much more intent upon their own aggrandisement than upon the welfare of the people. Year after year great bands of marauding rebels had moved across the once happy Flowery Land, marking their progress in the darkness of night by the glare of burning villages, or shadowing it in the day by the rolling smoke of consuming towns. A maniac usurper had not only sought to ascend the dragon throne, but had nearly done so, and had claimed divine honours; while invading armies of the outside barbarian had humiliated the empire, had visited the once inviolate city of Peking, and had burned the palace of the Son of Heaven.

Woe unto poor China, and her unhappy Emperor. A vivid and tragic depiction of the destruction of the Summer Palace, mentioned here, can be found in How We got into Pekin: A Narrative of the North China Campaign of 1860 by The Rev. R.J.L. M’Ghee (1862), which is a very worthy book.

I think this highlights the basic model that the British and other Europeans used to conquer big chunks of the world.

Places like China were filled with brave and skilled warriors. What they lacked, however, was competent and skilled leadership and organization. In the vast majority of non-Western cultures, military leaders (indeed all leaders) were picked based not on merit but on their family and their specific position within a family. This meant that they usually had second and third rate talent in the officer corp. Individuals were loyal to their family first and to any external entity second if at all. This led to corruption and indifference to the welfare of the men. Their armies were often little more than poorly trained mobs who depended on mass to win.

Since officers and NCOs usually comprise only 5% or less of total force, Westerners could create large, competent armies seemingly out of thin air just by supplying merit selected officers with Western organizational training and expectations. Small, highly trained and highly disciplined forces routinely defeated the mob armies.

Taiping Rebellion is very interesting in itself. It is one of those great conflicts unknown to most Westerners and even most Asians outside of China. Some histories rank the deaths in the conflict as high as 60 million (compared to WWII’s 42 million) making it the bloodiest war in history.

What they lacked, however, was competent and skilled leadership and organization. In the vast majority of non-Western cultures, military leaders (indeed all leaders) were picked based not on merit but on their family and their specific position within a family.

This is still true of most Arab armies. It is unknown what the situation with Iran is but no one is likely to invade Iran. If they attack Israel, they will be flattened with nuclear weapons.

Shannon, that is certainly correct. Some groups were less good as basic material for armies, others were what the British called “martial races”. This is now dismissed as racist mumbo jumbo, but the people who did this sort of thing for a living were certain of it and I don’t doubt they knew what they were about. Where you had the basics in place, a leavening of European officers would be sufficient. Kipling has a poem about this, specifically training the Egyptians into an effective army, which well describes the process, though of course it lacks the racial sensitivity of our era.

Shannon….In addition to leader-selection criteria, the culture of a society, and of a particular military organization within a society, has a major impact on victory or defeat. In 1797, the Spanish naval official Don Domingo Perez de Grandallana analyzed the reasons why his country was repeatedly defeated by the British in naval engagements:

“An Englishman enters a naval action with the firm conviction that his duty is to hurt his enemies and help his friends and allies without looking out for directions in the midst of the fight; and while he thus clears his mind of all subsidiary distractions, he rests in confidence on the certainty that his comrades, actuated by the same principles as himself, will be bound by the sacred and priceless principle of mutual support.

Accordingly, both he and his fellows fix their minds on acting with zeal and judgement upon the spur of the moment, and with the certainty that they will not be deserted. Experience shows, on the contrary, that a Frenchman or a Spaniard, working under a system which leans to formality and strict order being maintained in battle, has no feeling for mutual support, and goes into battle with hesitation, preoccupied with the anxiety of seeing or hearing the commander-in-chief’s signals for such and such maneuvers.”

More here. Note especially the WashPost link, which suggests that American society is increasingly driven by the kind of rule-driven micromanagement that Grandallana attributed to the Spanish fleet.

Ward was clearly an interesting individual, though I think you missed an excellent opportunity to use the Frazetta picture (the “Warlord” one Zenpundit is fond of) as an illustration. So, who’s a contemporary equivalent? Erik Prince? Tim Spicer?

We don’t often hear praise of scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes, adventurers, and fugitives from justice these days, Lex. Well, pirates and adventurers, maybe. What a marvelous piece of writing!

There’s a religious conundrum in there too, I think — a hint of an answer to the age-old question of theodicy.

*

I attended a presentation-seminar given by Ali A Allawi at the Jamestown Foundation a few years back, where he was speaking about Mahdist groups surfacing “under the radar” in Iraq, and suggested to him that memories of the Taiping Rebellion, and the huge losses of life involved in curtailing it, were behind the current Chinese government’s strong reaction to Falun Gong. Allawi’s response was that similar memories of the Babist / Baha’i uprising were behind the swift response of the Najaf religious and civil authorities to the “Soldiers of Heaven” incident during the Ashura pilgrimage in January 2007.

*

There is so much going on in this thread that interests me, as a writer, a researcher specializing in millenarian movements — and as the son of a British naval officer. David Foster’s comments from Don Domingo Perez de Grandallana answer a question that’s been in the back of my mind for years — where the notion of the Navy as having a more independent-minded (could I say, “distributed”) sense of command than the Army came from.

I hadn’t realized it was so specific to us Brits.

It’s worth mentioning another notable American mercenary in recent Chinese history:

Homer Lea

Not only a hunchbacked dwarf mercenary general for Dr. Sun Yat-sen, but a writer of some of the first geopolitical works written by an American:

The Valor of Ignorance (1909)

http://www.archive.org/details/valorofignorance00leahuoft

Predicted the rise of an imperialist militarist Japan that would cause irritations for the U.S.

The Day of the Saxon (1912)

http://www.archive.org/details/dayofsaxonhomer00leahuoft

Predicted the rise of an imperialist militarist Germany that would cause irritations for the U.S.

Wikipedia reports that Lea died before he could start working on a book called The Swarming of the Slavs that would have predicted the rise of an imperialist militarist Russia that would cause irritations for the U.S.

Charles, have you read N.A.M. Rodger’s Command of the Ocean? (This has got to be on the top 10 list of books I’m always citing for all sorts of purposes.) It shows how some of the aspects of command we think are “self-evident” took centuries to evolve, and for the most part evolved in England long before anywhere else. For example, the principle that there should be a separate naval hierarchy based on talent, or at least seniority, in which the highest-ranking aristocrat (in terms of his inherited title) did not automatically get command of ship or fleet. The English navy had commoners in command over titled aristocrats (actually, few of the latter went into the Navy to begin with — it was a middle-class service) centuries before the French or Spanish did; in fact, until the French revolution commoners couldn’t become officers at all, except in some of the technical arms.

Even such concept as the captain of a ship having to obey the squadron commander in battle, or the captain being pre-eminent in the ship took a long time to be established. In the middle ages the commander of army troops on a ship was senior over the captain, who was considered to be a species of bus driver. Even the idea of Marines as being subject to the Navy, (originally Marines reported to the Secretary at War; it took decades before they were put under the Admiralty) or being trained to act on their own initiative, took, likewise, decades to evolve.

This probably has a lot to do with the superior social mobility of England versus the continent, and the relatively porous nature of the aristocracy.

“Some groups were less good as basic material for armies, others were what the British called “martial races”. This is now dismissed as racist mumbo jumbo, but the people who did this sort of thing for a living were certain of it and I don’t doubt they knew what they were about. Where you had the basics in place, a leavening of European officers would be sufficient.”

Is it more tribe or ethnic group or “culture” that we are talking about in that instance?

I ask, speaking as a descendent of those “martial races”:

A lot of half-formed ideas, well, inform the Jat-Sikh gang culture of Vancouver, etc. (I was raised Hindu but for my more rural relatives, Jat “trumped” religion in terms of marriage etc.)

– Madhu

British India stirs odd emotions in me, being an American of Indian origin. I’m a rabid anglophile and not a rabid anglophile all at the same time :)

[Comment removed by request of commenter. Jonathan]

By the way, do you know there is an Australian band called British India? Not half bad, either.

– Madhu

Last one:

This is the sort of thing that I mean by “informing” gang culture:

Apparently, from some Indian diaspora webistes I used to read, this sort of thing is romanticized. Well, that’s human beings for you :) Even I read that stuff and think, hmmm, that’s interesting….

– Madhu

Charles…British army vs British navy: “the notion of the Navy as having a more independent-minded (could I say, “distributed”) sense of command than the Army”

Perhaps partly due to the geographical/technological realities of single ship or task group command in an era before wireless…maybe also the fact that “purchase” of commissions was never used in the navy in the same way as in the army, AFAIK, played a part.

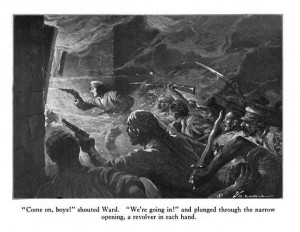

Chris, I used a picture of Ward himself, from the book I quoted.

Not sure who a modern equivalent would be. It is hard to pull off that sort of thing nowadays.

Here is a toy soldier depiction of Ward leading the EVA, but with a stick instead of two revolvers. I bet in real life he had two revolvers.

Charles Cameron said “We don’t often hear praise of scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes, adventurers, and fugitives from justice these days,….”

Ah, but you neglect to use the adjectives of “successful and enterprising” in the description of these mercenaries – one must give the devil his due, as they say.

Tyouth:

Ah, but it was the delicious multilingual English of “scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes” rolling off the tongue that I was after – even “adventurers, and fugitives from justice” sounded a bit bland compared to the rest of them!

My point is that the dramatic, story-telling mind of a creator relishes precisely those dark passages in the swirling chiaroscuro of life which puzzle those whose preference is for all beginnings, middles and endings to be happy.

As poet, this doesn’t seem paradoxical to me at all, but as a student of religions I know it does to others – it’s called “the problem of theodicy” and people are still trying to “solve” it.

Jim, Hi:

No, I haven’t read Rodger, and will keep an eye out for it.

Do you happen to know when (and why) the Navy (RN) came to be known as the Senior Service?

Hello, Madhu:

Perhaps you could write up a post about the “Jat-Sikh gang culture of Vancouver” at some point I know nothing about it beyond your comments here, but the crossover of religious and gang identity is one that’s of considerable interest to me, see my post Mexico, Africa, Zarqawi?

David:

I’d understood the idea that navies before wireless might have limited communications (or indeed turn a “blind eye” to them on occasion), but not that the British would be able to adapt better to this circumstance than, say, the Spanish – this whole conversation is very educational for me. Thanks.

Charles, I agree that this writer, Powell, is a poet in his use of words. The whole book is like that, with a good touch for the sound and feel of the words as well as the sense and meaning. Here is one more good snippet:

As to poetic influence in the narrower sense, I noticed only after I posted this, and only after I added the comment linking to Kipling’s “Pharaoh and the Sargeant,” that Powell’s phrase “… entered them in battle on a most astonished foe” is a direct quotation from that very poem:

Said England to the Sergeant, “You can let my people go!”

(England used ’em cheap and nasty from the start),

And they entered ’em in battle on a most astonished foe —

But the Sergeant he had hardened Pharaoh’s heart

Which was broke, along of all the plagues of Egypt,

Three thousand years before the Sergeant came

And he mended it again in a little more than ten,

Till Pharaoh fought like Sergeant Whatisname.

My memory is better than I was consciously aware of, apparently.

I only just now looked up Mr. Powell himself. He is manifestly a gentleman whose further acquaintance I must seek out.

As to the Taiping Rebellion, it is the most strangely under-studied major modern event I can think of. It was by reliable account the bloodiest and most destructive conflict of the 19th Century, yet very few Americans have heard of it. I suspect that it would have many lessons about fighting against, or creating, a religiously-based revolutionary movement. Moreover, it has had a major impact on Chinese thinking to this day, including official hostility to Christian missionary work in China, as you note.

On the issue of the Royal Navy, remember that Britain’s enemies always had to treat their navies as luxuries, and land armies as necessities for survival. With Britain it was the other way around. Further, you can put together an army “on the fly” and it may or may not work well for you. But a Navy cannot be built and run intermittently and haphazardly and episodically. You have one way of thinking for fighting land war, then you have to try to do the best you can making those individuals into naval commanders. This does not usually end happily. The British benefited greatly by never facing an unremitting naval foe, but rather a series of naval “surges” by their enemies over the centuries. As a result, Brittania’s enemies never had the hard-won, bone-deep know-how that the officers and Jack Tars of the Royal Navy brought to every watery affray. Of the five major threats presented over the last five centuries to British (then Anglo-American) naval power (Spain, France, Germany, Japan, Soviet Russia), the most dangerous was France. It won the Battle of the Capes, securing the independence of the USA, making it probably the single most consequential naval battle in history. But, alas for the French navy, the future was only Trafalgar and a long passing into England’s shade.

Madhu’s comment about the martial races leads me to suggest scrutiny of The Martial Races of India (1933) by Sir George MacMunn. It appears to be a late compendium of British wisdom and practice on the subject. The fighting qualities of the Jats are duly noted by MacMunn. It comes as no surprise that modern young men of Jat or Sikh ancestry, in search of stirring tales of courage and tenacity, would seek out the many books from the time of British rule which extol the fighting qualities of their ancestors. These stories lift the chin and straighten the spine just as they are, to any reader the least bit open to such stimuli. (I raise my hand.) How much more so if you are told, “these are your fathers, and this is how they were: They fought like tigers, they faced hardship without flinching, they were loyal to the last drop of blood draining from the bullet holes and saber slashes. Their strength was in their blood and their bones, and it is in yours as well. You are one of them.” It was an intoxicating vintage in its time, and I have no doubt the same dusty bottles, opened today, would be no less inspiriting. What sensible street gang leader would fail to make use of such material?

I note that MacMunn’s India and the War (1915) has some lovely color illustrations. Here is a Risaldar Major of the 14th Murray’s Jat Lancers.

Charles Cameron, you’re a poet! How nice for you but it doesn’t seem relevant somehow.

“We don’t often hear praise of scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes, adventurers, and fugitives from justice these days, Lex.” That’s a shot at who the Ever Victorious Army was and what they did, (consciously or unconsciously) you are critical in all of your descriptive terms.

I can appreciate your comment WRT the theocity question and the EVA (although it is, I think, obscurely tangential to the main story – with respect, you do meander). It does make it hard to believe that you are really at peace with theodical aspect of the characters from the way you’ve described them (no praise for their admirable qualities), now that you re-mention it.

Tyouth:

I wrote, “We don’t often hear praise of scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes, adventurers, and fugitives from justice these days, Lex. Well, pirates and adventurers, maybe. What a marvelous piece of writing!” I am taking delight in the words used by the author Lex quotes, “scum, pirates, dacoits, brigands, desperadoes” and so on, precisely because they sing, because they have poetry.

For that reason, I think that my mentioning that I am a writer and a poet is relevant.

I then wrote, “the dramatic, story-telling mind of a creator relishes precisely those dark passages in the swirling chiaroscuro of life which puzzle those whose preference is for all beginnings, middles and endings to be happy”.

My own theological understanding is that of a writer admiring a very great and varied creation, rather than that of a “good” person despairing of a world of depravity. I can imagine a Creator who takes delight in his dacoits and desperadoes — the words are not words of criticism when Powell uses them, I believe, nor are they when I quote him.