I recently read Fermor’s two travel books, set during his walk from Holland to Constantinople in 1933-34, A Time of Gifts: On Foot to Constantinople: From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube

Fermor’s greatest feat was kidnapping the German commander on Crete during World War II.

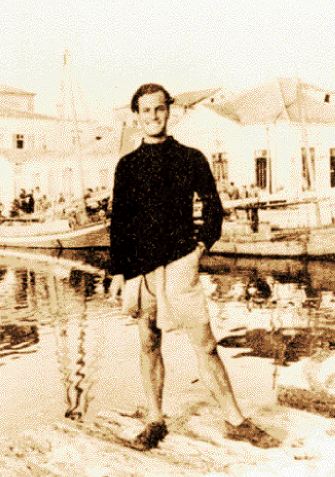

This site is dedicated to Fermor’s life and career.

At 18, Fermor traveled extensively around Germany–this was shortly after Hitler came to power–and had many conversations with young Germans, mostly over mugs of beer:

“In all these conversations there was one opening I particularly dreaded: I was English? Yes. A student? Yes. At Oxford, no? No. At this point I knew what I was in for.

The summer before, the Oxford Union had voted that “under no circumstances would they fight for King and Country.” The stir it had made in England was nothing, I gathered, to the sensation in Germany. I didn’t know much about it. In my explanation””for I was always pressed for one””I depicted the whole thing as merely another act of defiance against the older generation. The very phrasing of the motion””“fight for King and Country”””was an obsolete cliché from an old recruiting poster: no one, not even the fiercest patriot, would use it now to describe a deeply-felt sentiment. My interlocutors asked: “Why not?” “Für König und Vaterland” sounded different in German ears: it was a bugle-call that had lost none of its resonance. What exactly did I mean? The motion was probably “pour épater les bourgeois,” I floundered. Here someone speaking a little French would try to help. “Um die Bürger zu erstaunen? Ach, so!” A pause would follow. “A kind of joke, really,” I went on. “Ein Scherz?” they would ask. “Ein Spass? Ein Witz?” I was surrounded by glaring eyeballs and teeth. Someone would shrug and let out a staccato laugh like three notches on a watchman’s rattle. I could detect a kindling glint of scornful pity and triumph in the surrounding eyes which declared quite plainly their certainty that, were I right, England was too far gone in degeneracy and frivolity to present a problem. But the distress I could detect on the face of a silent opponent of the régime was still harder to bear: it hinted that the will or the capacity to save civilization was lacking where it might have been hoped for.”

David, that scene is in the first book of the two, A Time of Gifts. Very much worth reading.

The books tie in with my interest in British travellers and adventurers on one hand, and the effect of World War I and the dissolution of the old order in Central and Eastern Europe.

I can’t recommend them enough – my English next-door neighbor in Athens when I lived there recommended them so highly that she loaned me her copy of “A Time of Gifts”, as well as “Roumeli” and “Mani” — which were about travels in Greece — and loved them so much that I went and ordered “Between the Woods and Water” when it was released … there was never a third volume of his travels, completing his journey to Constantinople. It was a vanished world, ripped apart by WWII, and then sequestered behind the Iron Curtain for decades.

I guess he didn’t live long enough to write it – just like G.M. Fraser didn’t live long enough to write about Flashman’s adventures in the American Civil War. (Damn, can’t you guys hold off checking out until you’ve written that one book that your fans have been waiting patiently for?)

“Ill Met By Moonlight” is not written by Patrick Leigh Fermor, but W. Stanley Moss, his co-conspirator in the kidnapping of a German general in Crete during WWII – it’s an absolutely smashing yarn, and recommended highly.

Another interesting travel writer is Harry Franck, who in 1904 journeyed around the world with basically no money–he describes the trip in “A Vagabond Journey Around the World.” My copy has disappeared, but it looks like Google has the whole thing, including the photographs.

Franck also wrote “A Vagabond in Sovietland,” describing his visit to the Soviet Union, and a lot of other travel books as well.

While we are talking about travel books, I would like to mention John Muir and his account of walking from Wisconsin in the aftermath of the Civil War to New Orleans (I think) where he joined a ship to sail round the horn to California. He landed in San Francisco and began to walk east to the Sierra. He walked to the Sierras and never left them. I read all his books many years ago when I was a member of the Sierra Club before it got into politics.

This is the best as it tells some of his stories of his youth. When he was at college in Wisconsin, he invented and built a desk for himself to force him to study.

David Foster: I discovered Fermor thanks to your 2006 post at Photon Courier–which was also the final impetus to subscribe to the New Criterion.

This comparison by the Telegraph was curious: “a modern Philip Sidney or Lord Byron”. Sydney died at 31, Byron at 36, both in the course of war. This fails to acknowledge Fermor’s achievement in living to 96 instead of dying in quasi-obscurity in WWII-era Crete.

Sgt. Mom, we may yet see the third volume of PLF’s memoirs. In his obituary in the NYT, it was reported that he had finished a draft of the book. I hope this proves to be true.

I too wish we had gotten to read Flashman’s memoir of his service (on both sides) of our Civil War. Not to mention his time in the French Foreign Legion, his service with the U.S. Marines at the seige of Peking, how he survived the fall of Khartoum and sundry other alluded to but never told episodes of his checkered career.

Turns out that Paul Rahe, who blogs at Ricochet, knew Fermor pretty well. Post here.

Thanks, David.

Terrific post by Rahe.

I wonder if he found out about any rebel slaves in the hills? That seems to have fallen out of the narrative somewhere.