One of the focal points in writing this History Friday column has been trying to answer the question “How would the American military have fought the Imperial Japanese in November 1945 had the A-bomb failed?” Today’s column is focusing on an almost unknown aircraft, the Curtis SC-1 Seahawk light patrol seaplane as one of many “reality lives in the detail” changes in material, training and doctrine that the US military was making for the invasion of Japan. Then placing the Seahawk in the wider context of the contrasting US versus Imperial Japanese fighting styles, of American “matériel battle” aka “Materialsclacht” versus Japanese “Samurai spirit.”

This is what Wikipedia has to say about the Curtis SC-1 Seahawk

“While only intended to seat the pilot, a bunk was provided in the aft fuselage for rescue or personnel transfer. Two 0.5 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns were fitted in the wings, and two underwing hardpoints allowed carriage of 250 lb (113 kg) bombs or, on the right wing, surface-scan radar. The main float, designed to incorporate a bomb bay, suffered substantial leaks when used in that fashion, and was modified to carry an auxiliary fuel tank.

You can see a nice You Tube video titled “SC-1 SeaHawk Seaplane Fighters in Combat Operations!” at this link:

The Seahawk served the US Navy from 1944 through 1948 and was replaced by helicopters. It is at best a footnote in the most detailed histories of World War 2. It is also a perfect metaphor for the fighting that would have happened, but didn’t, thanks to the ultimate in WW2 Materialsclacht…the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Materialsclacht is a German military word coined in November 1916 by Generals Ludendorff and Hindenburg after the battles of Verdun and the Somme. Roughly translated into English it comes out as either “matériel battle” or “attrition warfare.” In the original German it has a great deal more meaning; this passage from a 1 Nov 1916 letter from Hindenberg to Bethmann-Hollweg will give you a better sense of the meaning:

“The ever increasing “influence of the machine” meant that even the unquestionable “Spiritual superiority [geistige Ubergewicht] of the German soldier was not enough. Superiority in cannon, munitions and machine guns was also increasingly required. Germany must therefore double its munitions and triple its artillery and machine gun production by 1917.”

After that letter, the Germans retreated to deeply dug-in, concrete reinforced, positions on the Western Front’s “Hindenburg Line” for 18 months, to give them the breathing space to defeat the Imperial Russians in the East. Then they returned to squander their last reserves of hard to produce matériel and victorious troops from the East in a failed 1918 offensive that cost them the war.

This post-1918 offensive losing position was very much where the Japanese were in the Spring of 1945 when the commanding officer of the Japanese 32nd Army, Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, wrote the following (taken from “Okinawa: The Last Battle of World War II” By Robert Leckie):

“You cannot regard the enemy as on a par with you. You must realize that material power usually overcomes spiritual power in the present war. The enemy is clearly our superior in machines. Do not depend on your spirits overcoming this enemy. Devise combat methods based on mathematical precision then think about displaying your spiritual power.”

Ushijima’s success in doing just that and bleeding out the American 10th Army and III Marine Amphibious Corps at the price of his entire 32nd Army was the stuff of military legend.

So was what came next.

In the early hours of July 29, 1945, on a bright moonlit night, a kamikaze plane hit and sank the destroyer USS Callaghan (DD-792) at Radar Picket Station 9A, 60 miles southwest of Okinawa’s air defense “Point Bolo.” USS Cassin Young (DD-793) fought off other incoming planes while the destroyer USS Prichett (DD-561) went to Callaghan to take off survivors before the ship sank. The next night during the early morning hours of July 30, 1945, a “very slow plane” hit Cassin Young when stationed off the entrance to Buckner Bay. The crash killed 22 and wounded 45. Both ships were the victims of planes like the Yokosuka K5Y, an ancient wood and fabric bi-plane trainer whose construction made them too small a radar target for the 5-inch VT proximity fuse of the time to properly activate and who flew too low for the 1.5 meter “SC” type long wave length destroyer search radars to pick up among the clutter of land returns of Okinawa.

US Military “Ultra” code breaking reported in Thomas Allen and Norman Polmar’s book “Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan and Why Truman Dropped the Bomb” made clear the Japanese were going to convert 5,000 Yokosuka K4Y1, Yokosuka K5Y and Tachikawa Ki-17 bi-plane trainers into Kamikaze.

The “Spirited Japanese would have defeated the US Invasion of Japan with Stealth Kamikaze Bi-Planes” narrative is built around those Ultra messages and that series of engagements. (See “The Coming Kamikaze Threat in World War II We Never Faced” at this link: http://aviationtrivia.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-coming-kamikaze-threat-in-world-war.html for an example.)

The detailed reality of Operation Olympic would have been much different than this simplified narrative.

War is the ultimate human game of Darwinian evolutionary selection. The US Military and in this case the US Navy was making a massive change in its cruiser and battleship observation plane force structure between Operation Iceberg (Okinawa) and Operation Olympic (Japan) by doing a mass replacement of all earlier seaplane models with the Curtis SC-1 Seahawk by October 1945. This would have made a significant difference in dealing with the Kamikaze bi-planes.

The Curtis SC-1 Seahawk was armed with a pair of .50 caliber (12.7 mm) heavy machine guns, had a maximum speed of 313 mph (504 km/hr), could out-climb an F6F “Hellcat” to 6,000 ft. (1829 m), and could out-turn the brand new F8F “Bearcat”. The SC-1 had two underwing hard points each capable of carrying up to a 325 lb (147kg) depth bomb and a bomb bay in the float with the same depth bomb capability. (This was seldom used as the bay doors leaked after use; a fuel tank was usually substituted.) The SC-1 was faster than the Imperial Japanese Army Nakajima Ki-27 “Nate” and only 7 miles an hour slower than the Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” with the same machine gun armament. Think in terms of an American version of the A6M2 Zero based “Ruf” seaplane fighter.

There would have been 150 of them in US Naval forces as follows via Thomas Allen and Norman Polmar’s book Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan-And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb and Naval Aeronautic Organization, 23 July 1945

U.S. Naval Forces Available for Olympic/Majestic equipped with SC-1 —

FAST CARRIER TASK FORCE

14 CV

6 CVL

9 BB (4x SC-1 each)

2 CB (3x SC-1 each)

7 CA (2x SC-1 each)

12 CL (2x SC-1 each)

5 CLAA

75 DD

AMPHIBIOUS SUPPORT FORCES

12 CVE

11 BB (Older) (2x SC-1 each on nine OBB)

10 CA (2x SC-1 each)

15 CL (2x SC-1 each)

36 DD

6 DE

LOGISTICS PROTECTION GROUP

10 CVE

1 CL (2x SC-1 each)

12 DD

42 DE

In daylight the SC-1 would be able to intercept and shoot down wood and canvas bi-planes no sweat and tangle at low level with 2nd line and old front line Japanese Army fighters in daylight. Per US Navy doctrine of the time it would have been patrolling at low level on the flanks of the invasion fleet and in the low hills behind the landing beaches and ahead of the landing craft. This was exactly where the low and slow bi-planes would have to pass to get to American troop transports.

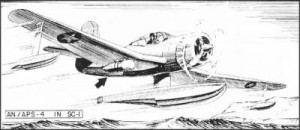

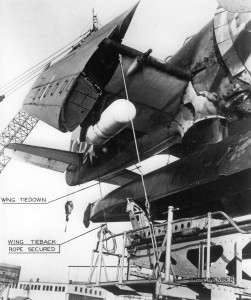

At night time, the SC-1 Seahawk had two very special surprises for the small numbers of large flight hour, night flying capable, instructor pilots (likely no more than 5%) of these bi-plane Kamikazes. The SC-1 was equipped with the pod mounted AN/ASP-4 surface search/air intercept radar! (See drawing above and the photo below.)

This 3cm/X-band radar could be used close to the ocean, unlike the destroyer “SC” radars and could see small bi-planes. More importantly, unlike the radar equipped F6F-3N and F4U-3N fighters, the Seahawk had wing slats that let it fly low and slow, as slowly as 80 knots (148km/hr), to land on rough seas. This meant that the Seahawk was uniquely suited to hunting the bi-planes that sank USS Callaghan and damaged USS Cassin Young.

Thus you see yet again, in a “reality lives in the details” small scale contest between American “Materialsclacht” versus Japanese “Samurai spirit,” bet “Materialsclacht.” Which, in fact, is what Pres. Truman did with the atomic bomb, he used it on a massive scale to crush Japanese “Samurai spirit.” And the world is a much better place because of it.

Naval Acronyms

CV Fleet Carrier

CVL Light Carrier

CVE Escort Carrier

BB Battleship

CB — Battlecruiser

CA Heavy Cruiser

CL Light Cruiser

CLAA Light Anti-Aircraft Cruiser

DD — destroyer

DE Destroyer escort

Notes and Sources —

1. Thomas Allen and Norman Polmar, “Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan and Why Truman Dropped the Bomb,” Simon & Schuster; First Edition edition (July 1995) ISBN-13: 978-0684804064

2. AN/APS-4 (ASH) Lightweight ASV and Interception Set

http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/radar-10.htm

DESCRIPTION: Lightweight airborne search and interception set primarily for carrier based aircraft. All major components are contained in a single pressurized housing similar to a Mk 41 depth bomb, and detachable in the same manner as an ordinary bomb.

.

USES: For locating and homing on ships and coastal targets; for locating planes and making interception approaches; and for navigating. Range, bearing and elevation data are given as B or modified H indications appearing on the same scope. Set operates with AN/CPN-6 racon, and has provisions for IFF connections for identifying targets.

.

PERFORMANCE: Reliable maximum ranges are 15 miles on surfaced submarines (broadside), 30 miles on 4,000-8,000 ton ship, 75 miles on well-defined coastline, and 5 miles on aircraft. Aircraft can be tracked to 300 feet. Range accuracy is ± 5%. Covers ± 75 ° in bearing. Bearing accuracy is ± 3 °. Covers -30 ° to +10 ° in elevation when searching, ± 30 ° when intercepting. Elevation accuracy is ± 3 °.

3. ASH Airborne Radar

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/A/s/ASH_airborne_radar.htm

Specifications:

Wavelength – 3 cm

Power – 1 kW

Range –

5 nautical miles (9 km) on aircraft

15 nautical miles (30km) submarine

30 nautical miles (55km) on merchant ship

75 nautical miles (140km) coastline

Accuracy – 3 degrees

Scope –

B scope at all ranges

G scope at shortest range

Weight – 180 lbs

Also known as AN/APS-4, the ASH airborne radar was mounted in Avengers escorted by Hellcats. It was intended to be a general purpose radar capable of both air and surface search as well as navigation and homing. The main components were mounted in a pod resembling a depth bomb that was mounted on a bomb rack.

.

The system had four range settings, for 4, 20, 50, and 100 nautical miles (6, 30, 80, and 160 km). The system was equipped with IFF.

.

Though rather too large and complex for effective use in fighters, a number of sets were installed in the F6F-5E Hellcat night fighter. These were eventually superseded by the much more suitable AN/APS-6 gunsight radar.

4. Airborne Search Radar RT-5A/APS-4 (USA 1943)

http://www.duxfordradiosociety.org/restoration/equip/aps4/aps4.html

5. ASH Radar Mounted on Curtis SC-1 Seahawk

http://navsource.org/archives/01/057/015701h.jpg

6. D.M. Giangreco , “Hell to Pay- Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1947”. Naval Institute Press, 2009.

7. Robert Leckie , “Okinawa: The Last Battle of World War II,” Penguin Books (July 1, 1996) ASIN: B00362AMFM

8. Naval Aeronautic Organization, 23 July 1945

http://www.history.navy.mil/a-record/nao-23-52.htm

PDF Page 24:

“For planning purposes BBU now using OS2U as substitutes for SC are assumed to be re-equipped with SC by Oct 1945.”

.

Page 25:

“For planning purposes CAU now using OS2U or SOC as substitute for SC are assumed to be re-equipped with SC by Oct 1945.”

CAU = Heavy Cruiser units

.

Page 26

“For planning purposes CLU now using OS2U or SOC as substitute for SC are assumed to be re-equipped with SC by Oct 1945.”

CLU = Light Cruiser units..

9. Radar Bulletin NO. 2A (RADTWO A) “THE TACTICAL USE OF RADAR IN AIRCRAFT,” Part Two RADAR SYSTEMS, PRINCIPLES OF OPERATION OF THE RADAR SYSTEM, Navy Department, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/RADTWOA/RADTWOA-2.html

10. Curtis SC-1 “Seahawk”, NavSource Online: Battleship Photo Archive

http://www.navsource.org/archives/01/57k2.htm

11. SC Seahawk, U.S. Reconnaissance Float Plane

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/S/c/SC_Seahawk.htm

12. Curtis SC-1 Aircraft, USSLittleRock.org

http://www.usslittlerock.org/Armament/SC-1_Aircraft.html

13. Curtiss SC Seahawk 1944, Virtual Aircraft Museum

http://www.aviastar.org/air/usa/curtiss_model97.php

Thank you for this installment. I had never thought of the scout seaplanes being used as a serious CAP, and I did not know about the climb and turn rate performance of the SC-1. To be honest, I thought of them as being restricted to either the search or spotting role. This is triggering some thought.

Subotai Bahadur

Boooook!!

Subotai Bahadur,

During the SC-1’s short time in service, the crews of the US Navy cruisers and battleships with Seahawks referred to them as “Quarterdeck Messerschmitts.” See the USS Little Rock link.

VXXC,

It is getting written one column at a time.

That is very interesting. I think a big risk on those scout planes would be that they’d get shot up by US anti aircraft weapons as they returned to their ships. But given the dangers that these picket ships faced it seems like this would be a good trade off.

Note also that “materialschlacht” is not simply a blunt instrument. It is a matter of increasingly devastating and effective machines, not mere mass of shells and bombs, as it is sometimes misconstrued to mean. The human frame and its spiritual component are constants, but the better and better armament they have to wield, or confront, change rapidly under wartime conditions. This qualitative aspect of the American materialschlacht in World War II was actually on a sharp upward slope in the closing months, as these posts show. The A-Bomb was just the most spectacular example.

Carl said:

>>…I think a big risk on those scout planes would be that they’d

>>get shot up by US anti aircraft weapons as they returned to their ships.

>>But given the dangers that these picket ships faced it seems like this

>>would be a good trade off.

All US Navy and USAAF aircraft at the end of the Pacific War were fitted with the Mark III Identification Friend of Foe (IFF) beacons.

There were several issues with them at the time.

1. Getting the proper code in the beacons. They were changed daily and long range patrol planes flying in/near Okinawa were chronically behind in the codes due to bases decoding the latest transmissions with the daily code late and not getting them to PBY, PBM, PV-1 and PB4Y patrol planes prior to their take off time. This was not an issue with ships in the fleet like the SC-1.

2. Keeping the IFF equipment properly operational. This was a problem for pretty much every air unit in the war.

3. Possible Japanese spoofing of the beacons since several Japanese radars could modulate to produce a US Mk III beacon response. This resulted in pilots turning off their IFF beacons close to their targets and forgetting to turn them on again flying back to the fleet. (This is a problem that is still present in today’s air operations.)

There were a number of technical fixes in terms of new beacons doing the IFF function that were connected with Project Cadillac airborne early warning radars, but the Pacific War ended before their widespread deployment.

The bureaucratic food fights between the services during the standing up of the Department of Defense resulted in a new IFF standard being delayed until after the Korean War.

” This qualitative aspect of the American materialschlacht in World War II was actually on a sharp upward slope in the closing months, as these posts show. The A-Bomb was just the most spectacular example.”

The most spectacular example of early failure was the Sherman tank. I have a book by a guy in a tank recovery unit in Normandy. The losses in armored units was 600%. By the end of the campaign, the crews were being dredged from infantry The title of the book is Death Traps and it is excellent although there are some newer reviews with good criticism of some of his technical points.

150 SC-1 vs 5000 Kamikazes? Would they have been overwhelmed? Plus, if the SC-1 are dogfighting, would the deck guns on the ships be quiet lest they hit their own planes?

Overload in CO

My dad was on the USS San Francisco (CA-38) during WWII (but he was a young one, missing Guadalcanal as he only got into the service in late ’43.)

For years I helped him edit the newsletter of the (now defunct) USS San Francisco (CA-38) Association; they had a few articles and a photo now and then of their scout aircraft. They used the biplane SOC throughout most of the war, but perhaps shifted to the OS2U (my google-fu is weak at the moment and I can’t find any specifics on the ‘Frisco’.)

The performance gains of the SC-1 over the SOC were huge: about twice the top speed, 2.5 times rate of climb and service ceiling (not sure how important the latter was in an observation aircraft!), yet still providing about the same range (and the SC also provided the ability to carry an auxiliary fuel tank.) Better armament, too. Quite an upgrade.

Overload in CO Says:

>>150 SC-1 vs 5000 Kamikazes? Would they have been overwhelmed?

Just because the Japanese Military said their “Ketsu-Go Six plan” to defeat the American invasion of Kyushu would use 5,000 wood and canvas Kamikazes to sink the American fleet, doesn’t mean they could really do it.

The American military got a vote — see the SC-1 deployment — on the Japanese carrying out their plans and American Ultra intelligence meant American commanders were reading Japanese Military mail faster than they could decode it.

There were three big and interrelated reasons that the Japanese Ketsu-Go Six Kamikaze coordination plans were going to fall apart like their aerial plans for the Marianas “Decisive Battle,” more commonly known as the “Marianas Turkey Shoot.” The consisted of the following:

1) Communications,

2) Maintenance, and

3) Flawed operational planning amounting to wishful thinking.

I’ll stick to the last point for now.

The Imperial Japanese Military liked big, complicated operational plans with lots of moving parts, where everybody got a piece of the action. This worked with the consensus style of Japanese leadership in that it let the various military factions participate with the least amount of political friction. When there was a lot of time to plan and collect intelligence. There were highly trained forces that had long lead times to execute rehearsals of the plan, and most importantly an unprepared foe. This style worked. It was the “Short Victorious War” planning style.

When the Imperial Japanese faced a prepared foe with anything approaching equal capabilities, they got locked in a war of attrition. Then when they went for the “Big Plan” decisive battles, they got their heads handed to them as the command consensus could not adapt to the changing realities fast enough and started to believe in fantasy

in order to cope.

Retreat into fantasy is the best way to describe Ketsu-Go Six’s operational assumptions.

At Kyushu, the Imperial Japanese would be facing a prepared American foe with superior capabilities that was reading their communications in real time and had a template of the Imperial Japanese fighting style to apply it’s overwhelming force upon.

True, the Japanese had successfully hidden a huge number of Kamikaze planes in Kyushu, Shokaku, Western Honshu, Korea and Formosa.

True they had hidden the fuel for them.

What was not true, and assumed to be so, was that the Japanese would have the ability to coordinate large numbers of them, with disparate flying characteristics (Think A6M2 Zero as compared to a Sopwith Camel), over a wide area to achieve large, hourly, time-on-target pulses of 300 Kamikaze at a time off individual landing beaches.

Which -is- what the plan assumed.

One of the old Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF) “Air Technical Intelligence” (ATI) reports I read spoke of a cave hanger with 13 ‘modern fighters’ investigated in Oct-Nov 1945. It went into detail about how well hidden the hanger was to include a description of the light rails with hand mine cars filled with vegetation constructed in front of the hanger entrance to hide it from the air. This part of this ATI report later showed up in a US Strategic Bombing Survey report on Japanese underground aircraft production facilities.

Then the FEAF ATI report spoke to the practical reality of this cave as a working hanger, which the USSBS report did not.

o There was one string of electrical lights run by generator, for which there was

limited fuel. Most work was done by torch or candle light.

o The cave floor was mud save for a wooden walk way.

o There were no vehicles to move the airplanes, only draft animals and people.

o There was no room to stage operational aircraft at the back of the cave past inoperative aircraft closer to the

cave mouth.

So come the day, if the facility was to get out seven aircraft, and the seventh operational plane was number 13 at the back of the cave. The entire cave had to be cleared of planes to get that plane airborne…by hand. And all the planes had to be placed back in the cave — or pulled away some distance from it and camouflaged — before day light or roving American fighter-bombers would pounce and napalm and fragmentation bomb the whole area, then seed it with M-83 butterfly-bomb scatter-able mines.

This facility would have been expected to handle further aircraft staged from elsewhere after the original planes were gone while American intelligence would be busy correlating pilot reports, radar plots and signals intelligence to steer day and night air patrols and photo intelligence flights looking for it.

A single plane crashing on take off or landing would be a smoking beacon drawing American fighter-bombers and medium bombers for miles around to come look.

Now multiply that example 100 times and you see after the first couple of days the Kyushu suicide campaign would have been a continual and irregular stream over several weeks and not a 10-day orgy of coordinated pulses Ketsu-Go 6 assumed would overwhelm American air defenses.

The American Military’s “vote” on Ketsu-Go Six also included a series of operational and tactical scale deception plans to get the Japanese to “show their hand” regards launching mass Kamikaze raids by using US Navy “Beach Jumper” deception units to replicate radar and radio traffic of an invasion fleet off Kyushu days before the real thing.

The Japanese intended to send many Kamikaze flights out without enough fuel to get back. Decoy invasion fleets engaged by such planes are a pure loss.

The specific issues with wood and canvas Kamikaze was that in daylight they had to be used in huge numbers to overwhelm American air defenses (Think P-51 Mustang versus several loaded down Sopwith Camels) and at night they had to have pilots good enough, with enough night time flight hours, with good enough night vision, to do twilight/night flying attacks. There would have been no more than 5% of the 10,000 or so Kamikaze pilots (500 pilots plus or minus a hundred) the Japanese had that fit that category.

The Beach Jumper decoy operations and American airpower would disrupt the daytime Kamikaze coordination all to hell and at night the American Fleet would coil into anchorages covered with machine generated smoke screens.

This would place those wood and canvas bi-plane instructor pilots out orbiting the smoked out transport areas where the American Destroyer and small combatant “Fly-catcher” surface screen was. A screen augmented by patrolling radar equipped F6F-5N Hellcats, P-61 Black Widows and SC-1 Seahawks.

The SC-1’s were going to be with the “Fly-catcher” screen in any case as Japanese small subs and suicide boats were going to be present and the Seahawk was designed to deal with them.

The Seahawk’s ability to go low and slow with an air intercept capable radar would make those instructor pilot bi-planes their meat.

‘The most spectacular example of early failure was the Sherman tank.’

You must be kidding. The Sherman was a reliable medium tank armed with a medium velocity gun based on experience from North Africa, where British tanks lacked the high explosive shells needed to destroy towed anti-tank guns. It was comparable to the common panzer mark 3 and 4 of the Germans, though outgunned by the less common Panther and Tiger heavy tanks.

The Sherman vs Tiger argument is a bit like arguing that cruisers are defective if they can’t beat a battleship.

“The Sherman vs Tiger argument is a bit like arguing that cruisers are defective if they can’t beat a battleship.”

No, I am not kidding and your comparison is silly. Early in WWII there were still a number of “treaty cruisers” around and they showed their weaknesses at Tassafaronga and elsewhere. Later cruisers were built like cruisers and not to a 1930 treaty by politicians.

The Russians had a better tank, the T 34. It was still a medium tank but far more survivable. The Sherman was not even that successful against the Pkw4. The Tigers were clumsy and had mechanical problems but the Panther and the T 34 showed what could have been done by 1944.

” This worked with the consensus style of Japanese leadership in that it let the various military factions participate with the least amount of political friction. When there was a lot of time to plan and collect intelligence. There were highly trained forces that had long lead times to execute rehearsals of the plan, and most importantly an unprepared foe. This style worked. It was the “Short Victorious War” planning style.”

I think this is very important. Churchill wrote about the Japanese difficulty with improvisation. He attributed it to the language but I think you are correct about the cultural connection.

Mike K,

Pretty much everything you think you know about the M4 Sherman in WW2 is wrong.

It isn’t my area of expertese, but I know where to look to find those that have it and their story is much different that the “Official Narrative.” Since the official narrative is much nicer to the professional reputations of Ike, McNair, Bradley, Patton and pretty much the entire generation of 1st String US Army senior flag leadership in the ETO, AKA “General Marshall’s men.”

See these links —

The Chieftain’s Hatch: End of the M4(75)

10.08.2013

http://worldoftanks.com/en/news/21/the_chieftains-hatch-end_of_75_M4/

The Chieftain’s Hatch: US Tank Guns

05.01.2013

http://worldoftanks.com/en/news/21/chieftains-hatch-us-tank-guns/

Chieftain’s Hatch: Ordnance Dept Tank Development

28.11.2012

http://worldoftanks.com/en/news/21/chieftains-hatch-ordnance-dept-tank-development/

The Chieftain’s Hatch: US Guns, German Armour, Pt 1

04.01.2012

http://worldoftanks.com/en/news/21/chieftains-hatch-us-guns-vs-german-armour-part-1/

The Chieftain’s Hatch: US Guns, German Armor: Pt 2

09.02.2012

http://worldoftanks.com/en/news/21/us-guns-german-armor-part-2/

This text excerpt is from the final link:

“…This transition of views does not derive from any decline in the qualities of US guns, nor any improvement in German armor. Rather it is a reflection of the changing nature of the combat that 6th Armored was involved in. It is, in effect, a microcosm of the growing maturity of user feedback, as the US Army learned first-hand what tanks had to be able to do, while also gathering real-world data on what their own guns and their opponents’ armor were actually capable of.

The US Army was not alone in going through this learning curve. The Germans struggled in 1941, when they discovered that their tank guns were inadequate against the Soviet T-34. The Germans also discovered at that time that their standard AP rounds had poor metallurgical qualities. It took about a year, until mid- to late-1942, before the Germans had effected their solutions to these issues.

The British found out in 1941 that their 2pdr gun was not good enough against their German adversaries. They managed to respond on the firepower issue within a year, as the 6pdr began to replace the 2pdr, but it was not until almost two years later with the advent of the 17pdr that the British truly got the anti-tank firepower they wanted.

For the US Army’s perspective, the M4 was very well regarded by both British and US tankers in Tunisia in 1942 and 1943. When paired with the M10 tank destroyer (and later the M18), it appeared that the US had everything that was needed. And so they would have, if the panzers they faced in France in 1944 were the same panzers they had faced in Tunisia in 1943. But they weren’t.

US Army Ordnance had developed the basic tools. The Sherman had a 75mm gun in 1942. The 76mm gun was developed specifically to fit as an upgrade in the Sherman in 1942, and was available in 1943. The 90mm gun was developed in 1943, and was available for tanks in 1944.

But there was no consensus that this was the right path to follow. Ordnance’s own flawed testing lulled Army Ground Forces and the commanders in the European Theater of Operations into a false sense of security. It was not until the cold hard realities of combat in Normandy that a clear picture emerged on the needs for better guns to defeat the panzers. And even here AGF and ETO waffled on their feedback, demanding immediate solutions in the Summer, then asking only for more of the existing designs in the Fall, and finally screaming for immediate solutions again in the Winter/Spring. But as with any major industrial/technological undertaking, there are no immediate solutions. Fortunately, Ordnance continued their development efforts regardless of the changing user feedback, and so had effective solutions available within less than a year of the first hint of crisis.

The US Army responded better and faster than either the German or British armies. But alas, even with under-performing US tanks and guns, the Germans had been defeated before the US response to the Panther could make its way to the forefront.

So what of the whole debacle anyway? Would the outcome have been significantly different had the M4(76) been the standard American tank instead of the 75mm variant? Probably not. Neither would have been of great effectiveness against the German frontal armour, and as we’ve seen, when not facing the front of the cats, the 75mm seemed quite good enough. Would the outcome have been any different had HVAP ammunition been available for the 76mm guns from June 6th 1944? Again, I doubt it would have been enough to make a huge difference, as the ‘engagement range’ was such that it would only have helped a small amount of incidents. Of course, if you were the tank crew involved in that particular incident, you would have had a much different view of not having 76mm HVAP. 90mm guns were of practical utility but were being churned out pretty much as quickly as hulls could be found for them.

Really the US was a victim of nothing more than poor intelligence. They underestimated the enemy threat, and failed to prepare for it accordingly. It wasn’t that they couldn’t build tanks capable of winning the war with fewer losses, they chose chose not to since they honestly believed what they had was perfectly servicable and didn’t warrant the issues with introducing the upgraded equipment. When informed otherwise by the Germans, they reacted with commendable speed whilst balancing out current operational requirements with future upgrades.

Kirk Parker,

See the following:

NavSource Online: Cruiser Photo Archive

USS SAN FRANCISCO (CA 38)

http://www.navsource.org/archives/04/038/04038.htm

Dicctionary of American Fighting Ships — CA-38

http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/s4/san_francisco-ii.htm