One of the more frustrating things in dealing with General Douglas MacArthur’s World War 2 (WW2) fighting style was how many ‘will of the wisp’ intelligence, logistical and special forces operations he created and that were buried in post-WW2 classified files in many military services of several nations, located on several different continents. Often times, when you go looking for one of these outfits, something completely different turns up. Such was the case with “Submarine Field Unit” of Section 22, General Headquarters, South West Pacific Area. And as it turned out, the submarine that the Field Unit operated on is sitting in a museum four hours drive from where I live in Dallas, at Muskogee, OK!

As I stated in my “MacArthur’s High Tech Radar Commandos” column, I have been on the trail of Section 22 for some time. Section 22 of MacArthur’s General Headquarters (GHQ) South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was his radar intelligence branch — what is referred to today as electronic intelligence or “ELINT” — under his Chief Signals officer General Aiken. It was made up of personnel from Australia, Britain, the Netherlands, New Zealand, as well as the United States Army, US Army Air Force, US Navy and the US Marine Corps. Most Section 22 personnel were Australian Military Forces (AMF) and not Americans. So most day to day reports — for instance casualty records — with which you build a unit history, will be in the Australian archives.

It turns out that the National Archive of Australia (NAA) has digitized and posted on-line a significant portion of Section 22’s analytical work in the form of a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) copy of the Section 22 “Current Statements,” AKA reports on Japanese radar site locations and excerpts of technical analysis of captured radar documents or components, covering the period of 14 January 1945 to 20 March 1945. In those 66 days Section 22 generated 43 “Current statements” numbered 0260 to 0302. What I read of the file demonstrated a high pressure, fast paced, operational intelligence organization providing timely “actionable” intelligence to fighting units across the SWPA.

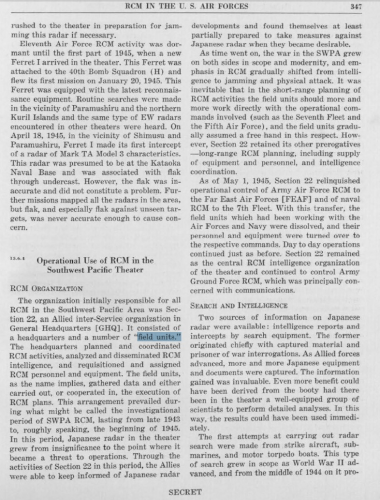

The Section 22 “Current Statement” that generated this column can be found on pages 10, 11, & 12 of 203 of the NAA file posted on-line. It was “C/S 0300 – 19 March 1945” and it delivered two important bits of intelligence and it had three things of interest for me as a columnist for this and future columns.

The bit for this column is in the photo below —

![<strong>Section 22 Current Statement 300 -- 19 March 1945 </strong> Source: RAAF Command Headquarters - RCM [Radio Counter Measure] current statements - Section 22, 676/4A11 PART 7, File National Australian Archive](https://chicagoboyz.net/wp-content/uploads/CS-300-Batfish-389x500.jpg)

An interesting item is contained in the monthly report of a Section 22 Submarine Field Unit.

“Most interesting intelligence of the month came from USS _______ Using the APR Receiver to detect Jap submarine on 156 mc PFR 500, she was able to home on sub by swinging ship from hull readings.”

Unpacking the WW2 military speak above, they were saying the following

1. We used our radar tracker APR-1 to detect a Japanese submarine radar,

2. The Japanese radar finger print was a radio frequency of 156 megahertz with a pulse repetition frequency of 500 pulses of radar signal per second, and

3. We used antenna’s on either side of the hull to figure out the direction of the strongest signal by turning the hull port or starboard and seeing that both antenna signal spikes on the APR-1 oscilloscope screen were getting larger equally.

The only submarine that whose war patrol record matches that February 1945 Section 22 monthly report document cited above was the USS Batfish on its sixth war patrol, December 30, 1944 – March 3, 1945.

Doing something like that with the vacuum tube electronics of WW2 took hours of training by a skilled instructor with years of in-the-field experience, with further combat experience for that RCM training to gel into efficient combat performance with the captain of the submarine trusting his RCM operators enough to maneuver his boat to “home” on an enemy submarine. It would take more than one war patrol with a really skilled RCM team to pull this off.

Unfortunately, this did not describe US Navy radio countermeasures (RCM) instructors or their submarine crew students of the Pacific Fleet in December 1944. The absolute priority for “RCM” (Electronic countermeasures or ECM in modern terms) was the European Theater until after the August 15, 1944 “Operation Dragoon” landings in Southern France. The U-boat Massacres of allied shipping on the American East Coast in 1942, plus the dual the technological shocks of German radio-guided missiles at Salerno in 1943 and jamming of Anglo-American 1.5 meter band naval and land based air warning radars in early 1944, gave the Commander in Chief (COMINCH) US Fleet Admiral King no lee way or political pull to divert skilled RCM instructors to Admiral Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet until after Operation Dragoon was over.

However, things were different for MacArthur’s 7th Fleet submarine flotillas operating from Freemantle and Darwin. Just as the failures of 1942 tied Admiral King’s hands with RCM, they opened the doors for the Australian Military with the fall of the British redoubt of Singapore. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) RCM experienced operator/instructors were withdrawn from Europe, India and the Mid-East to protect Australia in 1942. They created a radar tracking RCM training establishment in late 1942 that were better than anything available to the US Pacific Fleet in Hawaii until late 1944/early 1945.

A MATTER OF TIMING

At this point US Naval proponents and MacArthur haters (the Venn diagram overlap here is almost 100%) would challenge that because USS Batfish operated out of Hawaii for war patrol number six, where it nailed Japanese submarines I-41, RO-112 and RO-113. So how can I claim that it was a Section 22 Field Unit responsible for the Batfish’s performance, besides the Section 22 document?

The reason for the statement is a matter of timing. It turns out that all the USS Batfish’s war patrol documents are posted on-line by its Muskogee, OK War Museum linked to here —

http://www.ussbatfish.com/batfish-stats2.html

While war patrol #6 was from Hawaii after a major refit that added a 5 inch gun among other things to the Batfish.

The USS Batfish was based at Freemantle Australia for its war patrol #5 (October 8 – December 1, 1944) and the Batfish lost its primary APR-1 Elint operator on War Patrol #4 (July 31 – September 12, 1944), on 25 August 1944 due to nerves, and both WP #5 and #6 had much better RCM reports.

The Batfish torpedoed two Japanese escorts during war patrol #4 and looking at the small size radio room this APR-1 operator used, you can see why nerves might have been an issue —

The request for transfer during Batfish’s forth war patrol would have been enough time for Commander 7th Fleet Submarines (COMSub 7th Fleet) to send a request for a RCM trained replacement to Section 22 and for Section 22 to arrange for HMAS RUSHCUTTER, the RAN’s RCM training station, to either have a trained APR-1 crew waiting for it at Freemantle when Batfish arrived 12 Sept 1944 or have a priority training course available for the Batfish’s October 8, 1944 departure.

Also there is another timing corroboration. Since the sixth war patrol lasted from December 30, 1944 – March 3, 1945, the timing between the Batfish reporting that it nailed its first Japanese Sub in Early Feb 1945, and its reporting the full details how it did so to Pearl Harbor on March 3rd, is just enough time for that Mid-March 1945 Section 22 report in C/S 300 to be transmitted by safe hand air courier from Pearl Harbor to COMSub 7th Fleet and from him to that Section 22 document.

Given the US Navy’s RCM training priorities until August 1944, and when the Batfish lost its APR-1 operator in War Patrol #4, only Section 22 could get a trained APR-1 crew to Batfish in time for both training and combat experience to get its three Japanese sub kills.

So this column ends another journey into General MacArthur’s mysterious, extinct and under reported because it is inconvenient post ww2 historical narrative, Section 22 intelligence agency.

A submarine in Muskogee! What will we think of next? An igloo in the jungle?

Trent:

Have you investigated whether there is anyone alive from section 22?

Some interviews to capture any surviving personal knowledge would be good.

Gringo,

The Wikipedia article on how the Batfish got to Muskogee is a hoot.

Lex,

It’s about 10-years too late, sad to say.

The Wikipedia article on how the Batfish got to Muskogee is a hoot.

Yes, it is a hoot. Wanting to return the sub, and the Navy telling the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Commission- you have it, you keep it. No deposit, no return. Interesting that it got there at the best of submarine veterans from Oklahoma. One usually doesn’t associate Oklahoma with the ocean- or with submarines. Here is a Kate Wolf song that combines Oklahoma with seafaring. In China, or a Woman’s Heart.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Batfish_%28SS-310%29

This web post was updated with links to the tabular movement pages for “I-41”, “RO-112” and “RO-113” at http://www.Combinedfleet.com with the links embedded in the Japanese sub numbers above.

Check them out.