Source

Watching people blame the free market for the housing crisis is like watching the jocks that trip nerds in the hallway mock the nerds for their clumsiness. The commercial real-estate markets demonstrate what a nerd can do if left unmolested.

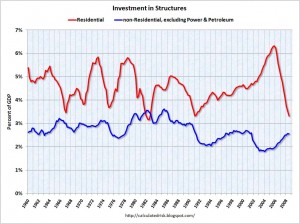

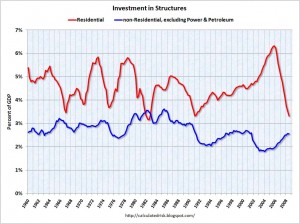

Leftists have to answer a question: if greedy, irresponsible, unregulated etc. capitalism caused the housing bubble, why didn’t we see a similar bubble in commercial real-estate markets which operate under even less regulation than the residential markets? Why does the politically neglected and unregulated commercial real-estate market exhibit much milder swings?

I dislike economics as a science due to its lack of empiricism. You usually can’t test any of the ideas in economics beyond looking at the historical record and squinting until your pet hypothesis snaps into clear focus. Then you argue with other people who don’t squint the same way you do. I am a libertarian/classical-liberal due to my understanding of the limits of economic knowledge. I know that people who claim to possess predictive economic models delude themselves and that any attempt to forcibly alter people’s economic behavior based on such delusional models will end badly.

Every once in a while, though, we get lucky. The differences between residential and commercial real estate provide the means to test the hypothesis that government intervention or the lack thereof caused the housing bubble and subsequent collapse of the financial system. We can compare the two markets because the same institutions ultimately make residential and commercial loans. They make loans in the same communities and regions. Changes in the economy affect both types of real estate at the same time and to the same rough degree. The only major difference between the two markets lies in the degree of government intervention.

Some might argue that the differences in financial sophistication between residential and commercial borrowers explains the difference. They argue that predatory lenders exploit naive borrowers in the residential market whereas they can not do the same for more-sophisticated commercial borrowers. We can dismiss this idea because in the free market financially sophisticated people assume the risk of lending for both residential and commercial mortgages.

Lenders make money on loans in two ways: (1) they either hold the mortgage itself for 20, 30, 40 years and take their profit long-term off the interest, or (2) they sell the mortgage in the secondary market. In both cases, financially sophisticated individuals judge whether the borrower can repay the loan. If the initial lender exploits unsophisticated borrowers, he suffers long-term if he holds the loan himself. If he tries to sell the mortgage the sophisticated secondary buyer will refuse to purchase it. In either case, no one in the system has an incentive to make predatory loans because anyone who does will directly bear the consequences of doing so.

Clearly, the problem lies in the way government actions sever the relationship between issuing risky residential mortgages and suffering the consequences of doing so. This not only allows predatory lending but also makes it difficult for lenders of good faith to judge when they make too many risky loans.

More than any other policy, the creation of Freddie Mac and Fanny May distorted the residential mortgage market in a way that the commercial market escaped. The FMs exist solely to induce lenders to make residential loans that the free market judged too risky. The FMs buy up residential mortgages from primary lenders and bundle them together in securities. They do so precisely in order to short-circuit the free-market feedback system that communicates to banks when the financial system as a whole has lent out as much money as it safely can. That feedback system worked like a governor on an engine. It kept the system from running away and lending more money than it could recoup, but also prevented people with poorer credit from getting loans.

Politicians who wanted the engine to run faster created the FMs to bypass the governor in order to get higher performance in the short run. Since the FMs would buy up almost any mortgage, lenders could make riskier and riskier loans without suffering any negative consequence. The FMs replaced the self-interested secondary-market buyers with people playing with government money and a mandate to induce more and more lending. Special dodgy accounting rules allowed the FMs to hide the risk behind the securitized mortgages they sold.

Tellingly, no such intervention occurred in commercial markets. The FMs’ charters expressly prevented them from buying commercial mortgages. As a result, the commercial mortgage market functioned with a free-market governor. When lenders made too many risky loans, free-market secondary buyers stopped buying their mortgages and the system cooled down. As a result, commercial markets saw no runaway boom and subsequent colossal bust.

The differences in the two markets proves as much as any observation can that political interference in the residential mortgage market ultimately caused the financial collapse. Had we been content with levels of home ownership that the market supported, and had we not tried to get something for nothing by blinding the financial markets, we would not be facing a crisis of this degree now.

Sadly, experience suggests that mere empiricism has no place in political economics.

[update (2009-2-12-9:52am): Rent control provides another dramatic example of the effect that government intervention in the free-market has on the residential housing supply versus commercial building supply. In places with rent control, residential housing is almost always in short supply while at the same time commercial space is abundant.]