Watching people blame the free market for the housing crisis is like watching the jocks that trip nerds in the hallway mock the nerds for their clumsiness. The commercial real-estate markets demonstrate what a nerd can do if left unmolested.

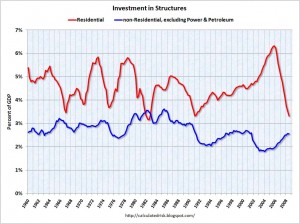

Leftists have to answer a question: if greedy, irresponsible, unregulated etc. capitalism caused the housing bubble, why didn’t we see a similar bubble in commercial real-estate markets which operate under even less regulation than the residential markets? Why does the politically neglected and unregulated commercial real-estate market exhibit much milder swings?

I dislike economics as a science due to its lack of empiricism. You usually can’t test any of the ideas in economics beyond looking at the historical record and squinting until your pet hypothesis snaps into clear focus. Then you argue with other people who don’t squint the same way you do. I am a libertarian/classical-liberal due to my understanding of the limits of economic knowledge. I know that people who claim to possess predictive economic models delude themselves and that any attempt to forcibly alter people’s economic behavior based on such delusional models will end badly.

Every once in a while, though, we get lucky. The differences between residential and commercial real estate provide the means to test the hypothesis that government intervention or the lack thereof caused the housing bubble and subsequent collapse of the financial system. We can compare the two markets because the same institutions ultimately make residential and commercial loans. They make loans in the same communities and regions. Changes in the economy affect both types of real estate at the same time and to the same rough degree. The only major difference between the two markets lies in the degree of government intervention.

Some might argue that the differences in financial sophistication between residential and commercial borrowers explains the difference. They argue that predatory lenders exploit naive borrowers in the residential market whereas they can not do the same for more-sophisticated commercial borrowers. We can dismiss this idea because in the free market financially sophisticated people assume the risk of lending for both residential and commercial mortgages.

Lenders make money on loans in two ways: (1) they either hold the mortgage itself for 20, 30, 40 years and take their profit long-term off the interest, or (2) they sell the mortgage in the secondary market. In both cases, financially sophisticated individuals judge whether the borrower can repay the loan. If the initial lender exploits unsophisticated borrowers, he suffers long-term if he holds the loan himself. If he tries to sell the mortgage the sophisticated secondary buyer will refuse to purchase it. In either case, no one in the system has an incentive to make predatory loans because anyone who does will directly bear the consequences of doing so.

Clearly, the problem lies in the way government actions sever the relationship between issuing risky residential mortgages and suffering the consequences of doing so. This not only allows predatory lending but also makes it difficult for lenders of good faith to judge when they make too many risky loans.

More than any other policy, the creation of Freddie Mac and Fanny May distorted the residential mortgage market in a way that the commercial market escaped. The FMs exist solely to induce lenders to make residential loans that the free market judged too risky. The FMs buy up residential mortgages from primary lenders and bundle them together in securities. They do so precisely in order to short-circuit the free-market feedback system that communicates to banks when the financial system as a whole has lent out as much money as it safely can. That feedback system worked like a governor on an engine. It kept the system from running away and lending more money than it could recoup, but also prevented people with poorer credit from getting loans.

Politicians who wanted the engine to run faster created the FMs to bypass the governor in order to get higher performance in the short run. Since the FMs would buy up almost any mortgage, lenders could make riskier and riskier loans without suffering any negative consequence. The FMs replaced the self-interested secondary-market buyers with people playing with government money and a mandate to induce more and more lending. Special dodgy accounting rules allowed the FMs to hide the risk behind the securitized mortgages they sold.

Tellingly, no such intervention occurred in commercial markets. The FMs’ charters expressly prevented them from buying commercial mortgages. As a result, the commercial mortgage market functioned with a free-market governor. When lenders made too many risky loans, free-market secondary buyers stopped buying their mortgages and the system cooled down. As a result, commercial markets saw no runaway boom and subsequent colossal bust.

The differences in the two markets proves as much as any observation can that political interference in the residential mortgage market ultimately caused the financial collapse. Had we been content with levels of home ownership that the market supported, and had we not tried to get something for nothing by blinding the financial markets, we would not be facing a crisis of this degree now.

Sadly, experience suggests that mere empiricism has no place in political economics.

[update (2009-2-12-9:52am): Rent control provides another dramatic example of the effect that government intervention in the free-market has on the residential housing supply versus commercial building supply. In places with rent control, residential housing is almost always in short supply while at the same time commercial space is abundant.]

Shannon,

I like your written stuff as much as I used to like hearing your comments in person, so please take this in the spirit in which it is offered: Please proof read and edit this article so I can send the link to some people.

Thanks.

John

(feel free to delete this comment)

John,

Sad to say I did proofread it. I’m essentially blind to mistakes if I know what I intended to write. I can’t see errors unless I let something set for a few days. I’ll have my spouse go over it.

I’ve been reading about this issue for a year. The early explanations pointed to the CRA/FNM/FRE combo. There is a lot of blowback to that position though, mainly from people like Barry Ritholtz. They blame Greenspan’s rate targeting 2001-2003 and securitization. In effect, they say that Wall Street encouraged the lending because they needed the mortgages to sell. Anyone that blames the CRA is a racist. In my opinion it was a perfect storm only made possible by the implicit government backing of the GSE’s.

Good analysis….

Before I proceed to my comment, I’d like to point out that it’s not freddie may, it’s fannie mae. So it’s freddie and fannie. I suggest you correct this or else you will be dismissed out of hand by your critics (and possibly your supporters) for not even knowing the names of the institutions you’re criticizing let alone what they do.

Now to my comments… I came to the same conclusion you did regarding the role that freddie and fannie played in this mess and the associated laws and regulations that controlled them. However I have not been able to satisfactorily answer the following. If freddie and fannie had the problem, (i.e. they were buying all the bad loans that the banks were generating), then I can plainly see why they ended up failing, But the banks should have escaped the problem since they were selling all the “bad” loans to the GSE’s. but that’s not the case – most of the big banks (citi, BofA, Wamu, Wachovia, Countrywide, etc etc) have or are in the process of failing also (and would have without the TARP funds). How do you explain that? If I was a banker I would have made sure the loans I kept in house were solid. I’m curious to know your take on this. In general I agree with your proposition, but the explanation may be a bit more involved than what you (and I) have come up with.

There is one weakness in dismissing the predatory loan arguement. Obviously a key element of the crisis was the mis-pricing of the risk of a broad collapse in home prices. If the bank assumed it was protected from the risk of default by the collateral, then it would certainly be more willing to make loans with a higher likelihood of default. HEL/HELOCs certainly have an element of this in them, as they typically charge a 2% premium vs a standard mortgage and utilize less stringent underwriting.

My sense is that this is much less of an issue than the Fannie/Freddie/CRA inspired trashing of lending standards. Still a lot of the more heart-pulling fraud stories involve behavior like this (the home-improvement contractor who talks a retired couple into a variable rate HEL on their house to do unneeded or overpriced work, who then get foreclosed on when the rate jumps up….)

Of course, if the banks had been smart predatory lenders, they would be making MORE money, not going broke…..

Aldo,

Thanks for catch on the Fanny Mae.

But the banks should have escaped the problem since they were selling all the “bad” loans to the GSE’s. but that’s not the case – most of the big banks (citi, BofA, Wamu, Wachovia, Countrywide, etc etc) have or are in the process of failing also (and would have without the TARP funds).

It has to due the systemic i.e. in the entire market, loss of value on properties even if the mortgages were sound. The banks assets on paper is the portion of the houses they still theoretically own through mortgages that have been completely paid off. If they loan someone 400,000 dollars to buy a house and then the market value of that house drops to 200,000, then the back has on its books a 200,000 unsecured loan. Even if the house owner makes their payments, the bank still has to adjust their accounting to reflect the loan hanging out in the wind. They have to adjust their on hand reserves to cover the possibility the mortgage will default. When the entire housing market tanks, all the banks have to do this simultaneously. This causes them to all stop lending and may cause them to be technically insolvent even if they have the same amount of money coming in the door as they did the day before.

The original idea of the TARP funds was to allow banks to continue to lend even when by law they could not lend because they had to account for the sudden drop in value of their mortgage properties. The drop was caused by the boom and the boom was caused by the FM’s buying up just about any mortgage the banks would right. The FMs did so because they weren’t playing with their own money. No private actors would behave in such a manner. Indeed, that is why the government felt compelled to create the FMs in the first place. They wanted more money to be lent than the free market thought prudent.

We can see this because the same explosion in lending and prices did not occur in the more commercial real estate market.

Robert,

They blame Greenspan’s rate targeting 2001-2003 and securitization. In effect, they say that Wall Street encouraged the lending because they needed the mortgages to sell.

Well, easy money certainly doesn’t help. For this we can blame Greenspan as well as foreign investors who have poured money into America over the last 15-20 years. Lots of money means low interest which prompts people to borrow. It doesn’t explain, however, the difference between commercial and residential lending. Easy money makes it easier for businesses to borrow as well.

Securitization no doubt hurt but securitization was an invention of the government. As near as I can tell, there were no major mortgage back securities prior to the founding of Freddie Mac and both the FMs together appear to be the major issuers of mortgage backed securities. In other words, the government forced something that the market would not have otherwise supported. As to Wall Street, they had just as much incentive to sell securities backed by commercial properties as they did ones backed by residential properties. Why didn’t they do so and do so recklessly?

@Aldo,

Well, it seems to me that Fannie and Freddie distorted the market so much that many of what would normally be considered good loans became bad loans.

What I mean is: People buy a house with an expectation the price will rise by 3%/year. Loans are approved on the basis of income vs. credit. Fannie and Freddie purchased risky loans, increasing the number of people who could now not only buy homes, but buy more expensive homes. That significantly increases demand for houses without increasing supply, thus, house prices rise. Non-Risky borrowers, having obtained their loan and having originally budgeted for 3% return on investment, now see and expect 10% return on investment, and use other credit vehicles accordingly (max out credit cards, buy cars, home equity loans for vacations, etc).

Now the Freddie/Fannie market collapses from too much dead weight. People default on loans in such numbers that the supply of cheap housing increases even faster than demand. That causes prices to drop.

Now the people who were originally non-risky (but who increased their debt based on expectations of future earnings) find that they not only aren’t getting 10% back, they’re not only not getting the original 3% back they expected, they are now, unexpectedly and inexplicably (to them) upside down in their mortgage, owing far more on their houses than those houses are worth. And then the stock market plunges due to fears of the Freddie/Fannie bunch taking the economy with it, so their investments (and expected earnings on those) plunge right along with it, making their financial position even more precarious.

And if the slowing economy results in a lost job, then the person has no choice but to default on a loan they can’t pay on a house they can’t sell.

So while there plenty of good loans/borrowers out there (like me!), even 20% of the supposedly good loans going bad would have a horrible effect on the big banks.

That’s the way I see it. I’m not a trained economist. I’m not even an untrained economist.

…and I see Shannon beat me to the punch.

Ah, well, it’s good to see my instincts/reactions were basically correct.

Phwest,

Still a lot of the more heart-pulling fraud stories involve behavior like this (the home-improvement contractor who talks a retired couple into a variable rate HEL on their house to do unneeded or overpriced work, who then get foreclosed on when the rate jumps up”¦.)

The problem with blaming predatory lending is that to assign it blame for the crisis you have to assume that the majority of loans would qualify as predatory. The fundamental problem is that in the residential mortgage market, loans to many different people pumped up the nominal value of homes across entire areas. If so many people can fall prey to that degree of widespread hucksterism then we have an all together more serious problem.

People who complain about “predatory” loans are usually inconsistent and they only label something “predatory” after the fact. If a lender refuses to lend to people because the bank thanks they can’t handle it, then their being discriminatory. In the case above, we would have heard a sob story about a kindly old couple who needed repairs on their house but the cruel bank wouldn’t trust them enough to give it to them. Lenders can’t protect people from their own foolishness. If you hire the wrong technical expert and then borrow money on his advice, that is not the banks fault.

The only way to guard against this is to require people to undergo training and take a test before they can manage their own finances and nobody would go for that.

Shannon…there *are* such things as commercial mortgage backed securities: see this Bloomberg story.

Given the investment chart you posted, one would expect that in a rational market the CMBSs would hold their value better than their residential equivalents, unless there has been a *very* long-term oversupply of commercial property.

David Foster,

Shannon”¦there *are* such things as commercial mortgage backed securities

Yes, but they are no where near as volatile as the residential market. Securitization is not really a problem as long as the secondary purchasers and their customers are playing with their own money. When the secondary buyer is playing with government money and selling with an implied government guarantee then that’s when you run into problems.

Remember, the entire point of the FMs was to induce the making of loans that the free-market thought to risky. Indeed, that has been the point of every government intervention in the mortgage industry dating from the GI bill forward.

The Bloomberg story makes it clear that the housing bust is bleeding over into the commercial markets. The housing bust is dragging everything down, not just sectors directly relating to mortgages.

In general, banks reduce their risk on commercial loans by requiring a 30% down payment, as well as the borrower’s business plan in order to assess the project’s viability.

Brent Richardson,

In general, banks reduce their risk on commercial loans by requiring a 30% down payment, as well as the borrower’s business plan in order to assess the project’s viability.

Yes and…? Why don’t they do so in residential lending? If commercial real estate lending is inherently more risky, shouldn’t we be seeing greater volatility in commercial lending than in residential?

Another factor: the impact of the media. Residential boom/bust cycles are certainly exacerbated by the positive feedback loops (vicious circles) created by the media, which in general acts as a cheering squad for anything that’s going well and a booing squad for anything that’s not. The effect of media coverage is probably considerably less in CRE than in retail.

David Foster,

The effect of media coverage is probably considerably less in CRE than in retail.

Perhaps, although business has its own media that could feed frenzies. I think that the major difference between residential and commercial is that people who buy commercial property don’t expect to make their fortune on the property itself. Instead, they view the property as tool to further their business. That creates different expectation about how much they should be willing to pay for the money they borrow.

Shannon,

A couple more points… In your initial statement you said:

“The FMs exist solely to induce lenders to make residential loans that the free market judged too risky. The FMs buy up residential mortgages from primary lenders and bundle them together in securities. They do so precisely in order to short-circuit the free-market feedback system that communicates to banks when the financial system as a whole has lent out as much money as it safely can.”

What you say is true, however, it begs the question: Who bought (and is buying) the securities that the FMs created? After all the FMs had to get the money to buy the loans that they bought from the banks from somewhere? The answer is the private sector – (pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, foreign and domestic, etc, etc). This begs another question: why would these private and supposedely financially sophisticated entities buy what essentially amounted to junk bonds? The reason is because they were given a AAA rating by the rating agencies such as Moody’s. And why would Moody give them such a high grade? Because the FMs were semi-governmental entities backed of uncle sam. (now of course they’re owned by uncle sam). So the growth of the FMs could have been nipped on the bud if the goverment had made it clear early on to the rating agencies that the government was not insuring the FMs! If they had done such a simple act the rating agencies would have given much lower ratings and there would have been much less private money buying the securities issued by the FMs.

In your response to me on why the banks are failing if they sold all the bad loans to the FMs and kept only the good ones, you stated that they’re failing because of the mark to market requirement. That’s a plausible explanation but is it actually the case? Do you have documentation showing that they are not holding a significant chunk of sub-prime loans? The reason I ask is because if they didn’t have any “bad loans” and all their loans were performing then they should be very healthy. It’s like me having an apartment building that has gone down in value, but my income has remained the same – I may not like the fact that my net worth has gone down, but as long as my cash flow remains intact and I can service my loan and have some left over, I’m pretty happy.

My gut tells me that the banks in trouble are holding a fair number of nonperforming subprime loans, and if so I do not for the life of me understand why they would have done that – if you have data that shows otherwise I’d be interested in seeing it.

Also do you happen to know if the mark-to-market rule impacts the banks’ income statement or just their balance sheet?

Aldo: “holding a fair number of nonperforming subprime loans, and if so I do not for the life of me understand why they would have done that”

Let me “speculate” (since I only know what I read in the papers, and that ain’t much) that they held them partially because they didn’t have enough buyers and they couldn’t sell cheap to create buyers without precipitating the crash. I also speculate that they knew what they were buying when they bought but because that was their business (buying and selling the tranches); and they wanted to be competitive with the FMs; and they could see IMMEDIATE profit they bought and sold; they bought the crap anyway.

My question is why didn’t the leaders of these big banks make public statements, cry out loud and strong – blow the whistle so to speak – about the essentially unfair, rash behavior at the FMs? No investigative journalism, no story on 60 Minutes. Probably that fat IMMEDIATE profit motive got in the way again but it seems that there would be one or two sharp, upstanding individuals in the upper echelons of the banking community….

Aldo,

The reason I ask is because if they didn’t have any “bad loans” and all their loans were performing then they should be very healthy.

The problem has nothing to do with whether the bank’s mortgage holders are paying their mortgages but rather with the sudden devaluation of the properties themselves. A bank’s assets, the ones used to calculate its assets, have nothing to the cash coming in from mortgage payments but rather the equity the bank holds in the property in the form of the mortgage’s collateral. In other words, accountants look at how much the bank could sell any particular house for if the mortgage holder could not pay. The broader market sets this value. No individual bank can control how this value rises and falls.

The crisis occurred not when people stopped paying their mortgages but when people stopped buy houses. Since the value of a house is only what people will pay for it, suddenly the value of the bank’s assets imploded even though they still had the same amount of money coming in the door everyday. Without those assets to show that they could repay depositors and investors, the banks became technically insolvent and had to stop lending money.

In other words, it didn’t matter how many subprime loans any particular institution held, it only mattered how much property they held as collateral in areas with real estate bubbles. Even banks that made nothing but rock solid loans were wiped out. For example, a small town bank in California would get screwed even if it hadn’t issued anything but rock solid mortgages for the last 50 years because the sudden collapse of real estate prices would mean that their assets are completely valueless even though their borrows pay like clockwork. Since they can’t sell the houses of those who might default, the only assets the banks own is the money that comes in the door everyday and that is not enough to run a bank.

The FM’s, by political design, disrupted the feedback between those who issued loans and loan defaults. This created a runaway feedback loop that caused lenders to lend to much and to inflate property prices. This in turn inflated the assets of banks on mortgages they issued long before the bubble developed. This encouraged them to lend more and sometimes the law required them to lend more.

Tyouth,

Probably that fat IMMEDIATE profit motive got in the way again but it seems that there would be one or two sharp, upstanding individuals in the upper echelons of the banking community”¦.

People did warn about the bubble and both Bush and McCain attempted to make the operation the FM’s more transparent and to bring their accounting standards in line with those of the private sector. The Democrats blocked both attempts. The central problem was the the FM’s destruction of free-market feedback signals created a system in which everyone benefited from the poor to the rich and in the public and private sector. No Democrat was going to go to the mat to stop people from getting homes even if those people couldn’t afford them.

The heart of this crisis is desire of leftist to trick the market into providing something for nothing. The entire concept of the FMs rested on the premise that the market was “irrational” and would not make enough housing loans purely from an exaggerated fear of not being paid back. If the government securitized the loans and guaranteed the securities, then the market would get over its “irrational” fears and lend money that people needed.

As we’ve learned there is no such thing as free lunch. People who can’t pay, can’t pay. You can’t trick the market to get around that fact. You can only blind it to the long term consequences.

Shannon,

you stated…

“The problem has nothing to do with whether the bank’s mortgage holders are paying their mortgages but rather with the sudden devaluation of the properties themselves. A bank’s assets, the ones used to calculate its assets, have nothing to the cash coming in from mortgage payments but rather the equity the bank holds in the property in the form of the mortgage’s collateral. In other words, accountants look at how much the bank could sell any particular house for if the mortgage holder could not pay. The broader market sets this value. No individual bank can control how this value rises and falls.”

If that’s the case then it’s a lousy accounting system. If I lend you 100K to buy a 150K house, what I should have in my books is a $100K debit as a loan to you and a $100K credit in the form of a promissory note (that happens to be backed by a collateral worth $150K). As long as you keep paying on the loan, what’s in the books shouldn’t change regardless of what the price of the house does – up or down. In the event you stop paying the loan and I end up foreclosing, then I will adjust my asset values (and balance sheet) accordingly. But I don’t (and shouldn’t do it) everytime the price of the house fluctuates!!

If this accounting rule (“mark-to-irrational-market-value”) is what’s ailing the banks, then it should be quickly remedied by changing it to the more rational and real rule I suggested, i.e. as long as the loan is being repaid, the loan should be marked to the value that it was made at.

As a comparison, do the banks mark all their unsecured loans (credit cards, signature, etc.) as having zero value since there is no collateral to back them up?