To be American is to forget…

Or, having exhausting every other opportunity to forget, to remember poorly.

In the course of a series of posts on how the United States of America has implemented selected clauses from its constitution…

- “To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions”

- “To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress”

- “The President shall be Commander in Chief…of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States”

- “No State shall, without the Consent of Congress…keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

- “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

…Dmitri Rotov has unearthed some forgotten yet particularly shiny pebbles:

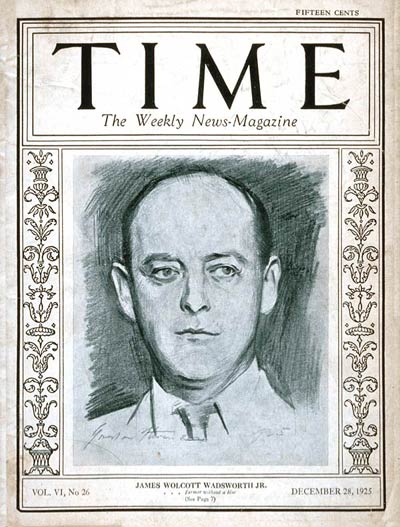

- The ill-starred military career of James S. Wadworth of New York, an ambitious New York Republican Party politician who Abraham Lincoln dragooned into the Army to neutralize him as a political threat. Wadworth who bungled along like a stereotypical “political” general but died well in the Wilderness.

John M. Palmer - By way of contrast, the distinguished military career of John M. Palmer, political general, friend of Lincoln’s, key supporter in Lincoln’s rise, and post-Civil War governor of Illinois.

Emory Upton - The tragic rise, death, failure, and victory of Emory Upton, professional soldier and Civil War prodigy whom William Tecumseh Sherman dispatched overseas to tour foreign military establishments and report back his findings. Upton’s reports, The Armies of Asia and Europe, published after his return, and The Military Policy of the United States, published in 1904, well after Upton’s death in 1881, heavily influenced future U.S. military policy. Upton also wrote Tactics for Non-Military Bodies: Adapted for the Instruction of Political Associations, Police Forces, Fire Organizations, Masonic, Odd-Fellows, and other Civic Societies, a book for which the world is not yet prepared.

James A. Garfield - Future president (and political general) James Garfield’s doomed attempt to implement Upton’s central idea: the “expansible army“. Says Rotov: “The expansible army consists of a large regular standing army, men and officers, with a capability of expanding further in crisis. Upton rejected the idea of a small standing army bolstered in war by militias and volunteers.”

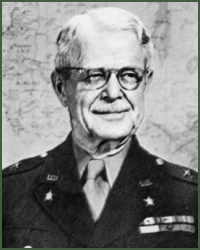

Peyton C. March, Sr. - The clash between Peyton C. March, the George C. Marshall of World War I, and Colonel John M. Palmer, grandson of John M. Palmer, before the Senate Military Affairs Committee led by Sen. James W. Wadsworth, Jr. (R-NY), grandson of James S. Wadworth.

Willard M. Romney, who cares - The curious case of citing the Militia Act of 1792 as a precedent for “Romneycare” and its child “Obamacare”.

This post in particular caught my eye:

With March’s “Uptonian” plan off the table, Wadsworth and Palmer began designing their own army. This (after political give and take) became the National Defense Act of 1920. There is a handy summary of what follows in The Second World War: Asia and the Pacific. I excerpt here at length:

Palmer’s ideas were not those of the majority of the Army’s general staff officers, who were disciples of the pensive Emory Upton, the Army’s most influential 19th Century theorist. […] The staff had updated the “expansible army” of John Calhoun and modernized Upton; but while it had convinced a reluctant chief of staff, Peyton March, to support the plan, it could not sell the program to Congress.

Palmer recommended a citizen-based army, which he felt was far more appropriate for a democracy. In his plan, while the Regular Army would be the vanguard of the ground forces, the National Guard and the Organized Reserves would provide the bulk of the wartime army. Citizen officers would command most of the citizen soldiers. In peacetime, the Regulars would train their associates in the Guard and Reserves. While Palmer also hoped for universal military service [in Swiss-type reserves – DR], this unpalatable position was not acceptable in peacetime.

The old Hamilton-Jefferson controversy between a purely professional and a militia-based defense force had been resolved in favor, once again, of the militia. Palmer had proposed an army in the American tradition. Politically feasible, the proposal was favored and accepted by the Wadsworth Committee. The Army’s official [March] program was discarded because it was too un-American, was so much of the philosophy of the Germanophile, Emory Upton. […]

All of this looked good on paper, but unfortunately Congress did not provide sufficient funds to implement the National Defense Act [of 1920] fully until 1940.

In other words, the infamously puny and underfunded interwar Regular Army was “half a loaf” – just a slice of the Wadsworth-Palmer plan.

There is a profound lesson in this for military theorists and planners. There is also an odd twist. Palmer lived to see the Act of 1920 funded…

p.s. To read more about the March-Palmer contest, you have to dig into out-of-print works like Toward a Post World War I Military Policy: Peyton C. March vs. John McAuley Palmer.

Palmer was a key architect of American strategy. He drafted his first plan for organizing the Army in 1911 under orders from Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Army Chief of Staff Dr. Leonard Wood. He played a major role in drafting the plan enacted as the Selective Service Act and operationalized as the American Expeditionary Forces. AEF commander John J. Pershing made Palmer his assistant Chief of Staff over in France. After the war, Palmer played a key role in reorganizing the Army, including the efforts Rotov narrates. At the beginning of World War II, Palmer friend and disciple George C. Marshall recalled Palmer (retired in 1926) to active duty as his special advisor. By the end of the war, as Rotov notes, Palmer was “the oldest American in uniform by the end of WWII” at age 75.

Palmer’s contribution is as fundamental to twentieth century American strategy formation as those of more famous men like Upton, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Billy Mitchell, or George Frost Kennan. Yet he merits little more than a Russell Weigley footnote.

I bought a vintage 1945 paperback of Palmer’s America In Arms (it has never been reprinted) to learn more. I’ve read two pages so far.

So far it’s gold:

Prologue

What is War?

A Diagnosis and a Remedy

I

The aspects of war involving weapons and modes of transportation have changed at each stage of human development. There is a vast difference between war as it was waged by Alexander the Great and as it is now fought by Rommel and Yamashita. But in its inner essence, war is the same now as was when an unknown conquerer built the first pyramid as a monument to his name and prowess. It is not a separate, isolated form of human activity. It is instead, as the German soldier-philosopher Clausewitz said a century ago, a special violent form of political action.

We customarily think that no two things can be more unlike than peaceful international relations and war-like international relations. And so we may be startled when we first grasp the thought that these are simply two phases of the same thing—human politics.

This was brought home to us in December, 1941. For years it had been the political program of Japan to dominate China and Southeast Asia and control the Western Pacific. When normal political action in Washington failed to gain our acuquiecense, Japan’s next argument was delivered at Pearl Harbor. Her purpose was still political and precisely what it was before her treacherous surprise attack. The only difference was that she used dive-bombers instead of diplomats.

II

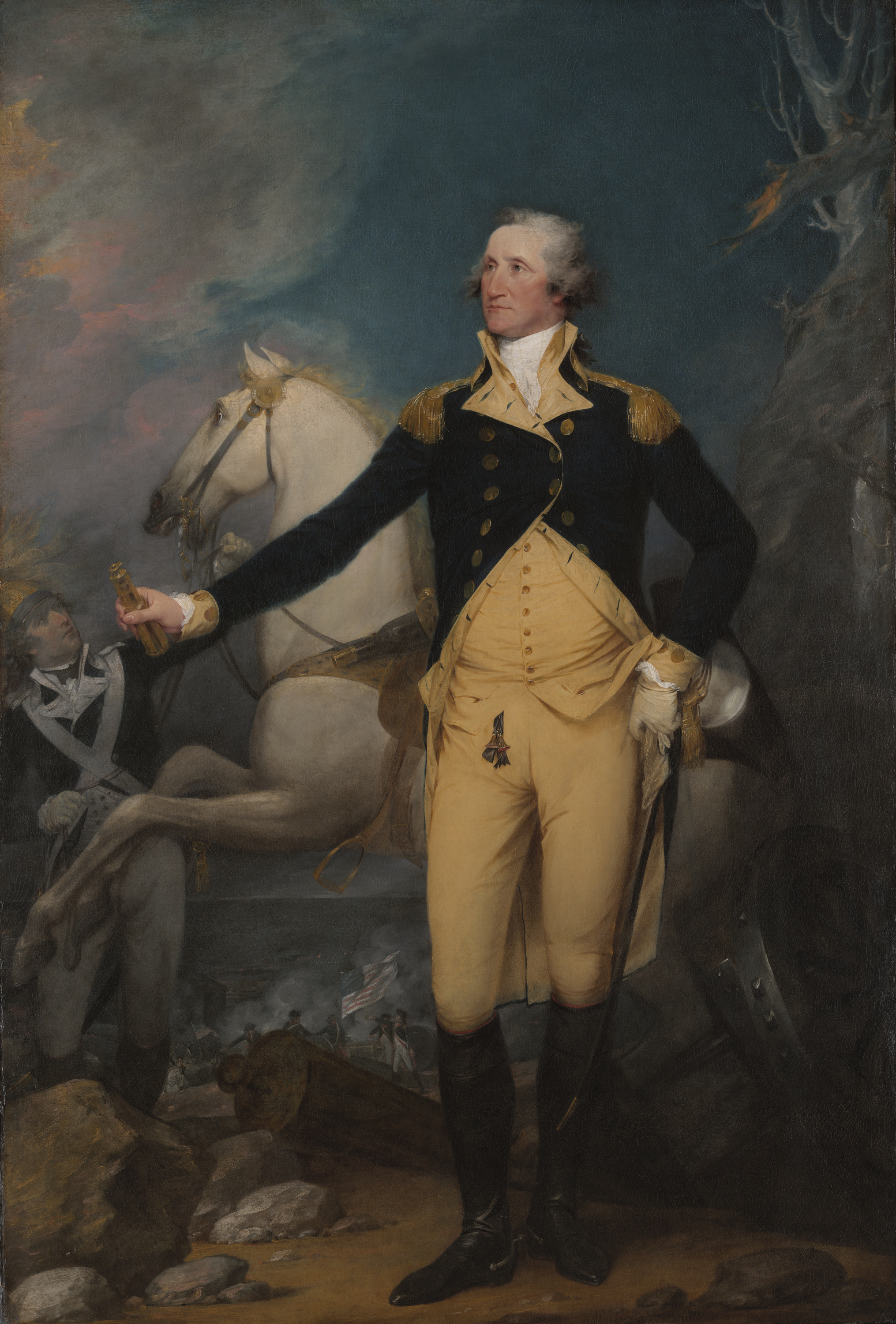

Even before Clausewitz, George Washington understood that war is simply a phase of politics. Thus when his countrymen called him to establish a new political system, he realized clearly that any complete system must include the machinery for dealing with that special violent phase of international politics known as war. This is the principle thought in his political writings from the close of the Revolution to the end of his life. In the light of his knowledge of war and its great significance in international affairs, his Farewell Address may be summarized as follows:

Rely on just dealings with other nations. Seek your legitimate political ends through peaceful negotiation and understanding. But lest some agressor impose the other form of political action known as war upon you, maintain yourselves in a “respectable defensive posture”.

If you do this other nations will not be tempted to depart from the normal and peaceful methods of political action in their dealings with you.

The non-aggressive military organization proposed by Washington to prevent normal political action from degenerating into the violent form known as war would have tended to preserve peace. But his countrymen ignored his advice for a century and a half. If he had been able to implement the new American republic with effective military institutions suited to a self-governing free people, Japan would never have dared to take a change of venue from the Court of Reason to the Court of Brute Force.

Palmer figures heavily in Eliot Cohen’s very good book Citizens and Splayers: The Dilemmas of Military Service.

Citizens and SOLDIERS that should be.

Great catch on some of the books. Why are good books forgotten and lost while others remembered?

Anyway, blog friends, I wonder how we got here all the time. I have begun to loathe the subject of foreign affairs and strategy….

– Madhu

JF,

Excellent post. I ordered the Palmer and Cohen titles.

The United States in 1789 was protected by the Atlantic and the Pacific. The USA was a natural fortress protected by an enormous moat. In the day of wooden ships an invasion by a million men was impossible unless ferried across the ocean by an armada of 10,000 wooden ships – assuming none sank. Preparing such an invasion could not be done secretly.

Furthermore, the US government was decentralized. Washington DC could be captured and burned to the ground and the rest of the US would not be crippled by the loss. There was no need for a large standing army. The only threat was from angry indians and small groups of malcontents. These a militia could handle.

However, the sinking off the Maine and the Lusitania, the attack on Pearl Harbor, the invasion of Korea, the sinking of the Maddox and the Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin, the destruction of the World Trade Center were events that forced the USA into war. Our Oceans do not provide any security – they provided only a false feeling of safety which has been repeatedly destroyed.

The solution after WWII was to create a very large navy that could make sure no one could bring a nuclear weapon across our oceans to destroy our cities. The navy did not patrol our coast. The world is now too small. Our navy patrolled the coastline on the other side of Our Oceans because that is the only way to protect America from a strike that can destroy all our cities in only 30 minutes after launch.

And, of course, we need boots on the ground on the otherside of Our Oceans to find and prevent these attacks. And we taught the world to speak English because we could not expect our troops to speak hundreds of different languages.

From time to time American Presidents and Congresses try cut back on troop levels and rely on Fortress America surrounded by unpatrolled seas. This always brings war and dead Americans.

General Wadsworth was beloved by his troops. His death at The Wilderness was considered by Grant to be the equivalent of the loss of a division. His death was from an act of recklessness to encourage his troops. He rode his horse along the line saying they had nothing to fear as the rebels could not hit an elephant. At that moment, he was hit in the head by a sharpshooter. Eleven generals were killed in the Wilderness battle.

Since immigrating to the US in the 1840’s, to Utah as Mormon converts from England, not one Romney male has ever served in any capacity in the military, nor post 9/11 any of his five strapping sons.

I suspect Mitt’s foundation for compulsory communitarian healthcare is more Mormon that martial.

Paul – I find that hard to believe – even in WW2?

Odd.

As a sixth-generation Mormon living in a majority Mormon state and, since my late mother worked for the LDS church for twenty years, as someone whose youthful medical bills were largely paid by the church’s own health care plan offered through its wholly (and privately) owned subsidiary Deseret Mutual Benefits Administration, I’ve never seen anything resembling “compulsory communitarian healthcare” (or “Romneycare” for that matter) either from the state of Utah or my church. Any Romney instinct for “compulsory communitarian healthcare” is more Michigan or Massachusetts than Mormon.

The church is opposed to government assistance since it harms the work ethic. This concern led the church to set up its own private welfare system during the 1930s in reaction to the New Deal. Growing up, my own family never had to go on government assistance because we were sustained by church welfare during periods of financial difficulty. Some of this assistance came in the form of funds from our local congregation but a lot came in the form of food grown on church farms, processed in church food plants, and distributed through church storehouses. We paid for the food by working in the store houses. Many church members volunteer to work in church facilities even if they aren’t drawing on church welfare (canning peas is one favorite activity).

I pay 10% of my income as tithes and offerings to my church. One reason is my own experience in having been on both the giving and receiving end.

“…Upton also wrote Tactics for Non-Military Bodies: Adapted for the Instruction of Political Associations, Police Forces, Fire Organizations, Masonic, Odd-Fellows, and other Civic Societies”

What a fascinating title for a book.

“…, a book for which the world is not yet prepared.”

Really now?

Would have thought something so old would at least be available–or at least excerpted–on Google Books or Archive.org or something–but I guess not.

Have you read it? What *exactly* is it about?

The non-aggressive military organization proposed by Washington to prevent normal political action from degenerating into the violent form known as war would have tended to preserve peace. But his countrymen ignored his advice for a century and a half.

Rather than ignore his advice, his countrymen economically recognized that the Royal Navy would ensure the security provided by their oceanic moats. Until it became clear that we could no longer depend on the benevolence of the RN at the turn of the 20th century there was no reason to spend for a defense that was being provided for free. Then the US began to develop a fleet second to none.

A larger or differently organized Army would not have dissuaded the Japanese from their action as the larger French army and Royal Navy did not dissuade Hitler because their calculations were based on their enemy’s will rather than its strength. Nor would one have dissuaded the British in 1812.

It is in the last 70 years that we have ignored Washington’s advice by entering permanent entangling alliances.

JF, Just finished the Palmer book…excellent from cover to cover. Thanks for recommending!