(A guest post by Grok, with editorial guidance from David Foster)

In the late 18th century, America was still a land where much of life’s daily rhythm was dictated by manual labor, especially in the essential task of milling flour. Oliver Evans, born in 1755, a visionary from Delaware, would set the stage for an industrial transformation with his invention of the automated flour mill. This innovation not only changed the way flour was produced but also marked a significant leap into the era of automation in America.

Before Evans, milling was a labor-intensive process. Grain, once ground into meal, needed cooling and drying, a job performed by “hopper boys” who would spread the meal across the mill floor, often walking over it to ensure even distribution. This method was not only physically demanding but also introduced potential contaminants into the flour.

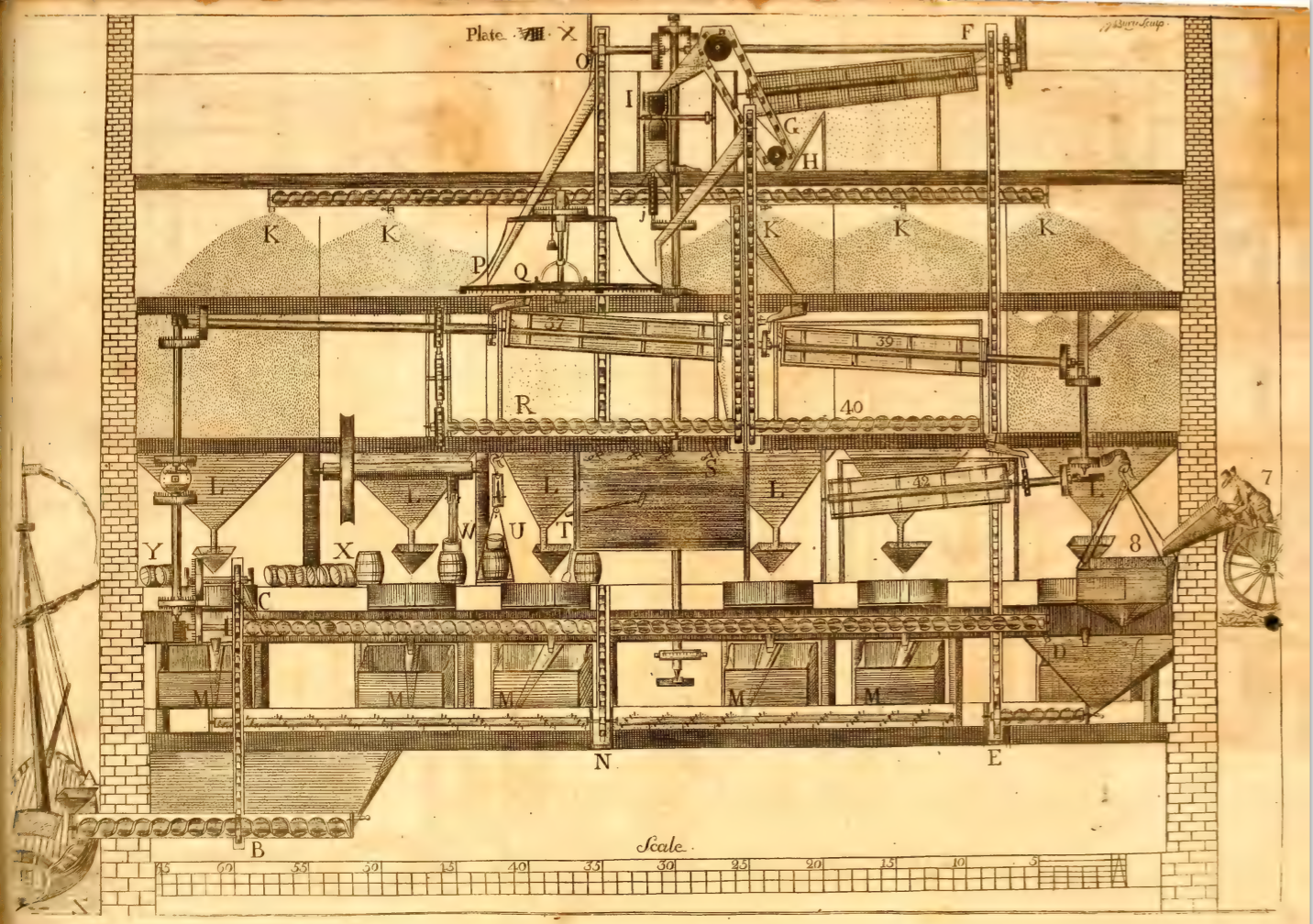

Evans’ revolutionary design, detailed in his 1787 publication “The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide,” introduced a system where human effort was significantly reduced through mechanical ingenuity. Here’s how:

-

Automatic Elevators and Conveyor Screws: Grain was lifted and moved using bucket elevators for vertical transport and the Archimedes screw, adapted into a conveyor screw, for horizontal movement. This was a significant departure from the muscle-powered methods of the past.

-

Self-Regulating Millstones: The grain was ground by millstones that adjusted themselves for consistency, eliminating the need for constant human oversight.

-

Mechanical Cooling: The role of the hopper boy was taken over by a machine of the same name, which used a rotating rake to spread the meal for cooling, ensuring hygiene and efficiency.

-

Automated Sifting and Packaging: The flour was then sifted and bagged without human intervention, making the process cleaner and faster.

The adoption of Evans’ system was slow at first due to resistance from traditional millers but soon spread like wildfire. By the early 19th century, it’s estimated that hundreds of mills across the United States were built or converted to operate on the Evans principle. Notably, within a few decades of his invention, from the 1790s through the 1820s, there were reports of over 200 mills adopting his methods, with some sources suggesting the number could be closer to 500 by the mid-19th century. This number reflects not just the mills directly constructed by Evans or his immediate associates but also those that adopted his designs independently or through licensure.

However, despite the widespread adoption of his technology, Oliver Evans did not reap the financial rewards one might expect from such a transformative invention. His patents, among the earliest granted in the United States, were often ignored or infringed upon. Evans spent much of his later life in legal battles to protect his intellectual property rights. While he did earn some income from selling rights to his mill designs and through his involvement in manufacturing, the financial success was not commensurate with his innovation’s impact. He also ventured into other fields, like steam engine design, but again, legal and financial challenges dogged him.

Evans’ automated flour mill was more than just an engineering marvel; it was a beacon for the future of industrial America. His work laid the groundwork for automation, reducing labor, increasing efficiency, and improving the quality of life by making food production more accessible and cleaner. His legacy, though not financially lucrative for him, has been a boon for generations, illustrating how one man’s vision could change the course of industry and daily life. His story is a reminder that innovation often comes with its battles, but its impact can endure far beyond the lifetime of its creator.

***

(The automated flour mill had been on my list of retrotech posts for a while, thought I’d try the lazy man’s way and let Grok do it. I did have to give it multiple prompts to improve the result, and also found and added the image manually. Also, paragraph breaks were lost, which is common when copying anything into WordPress; I fixed some but not all of them by editing the HTML)

If you look at a modern flour mill, you’ll see a lot of similarities with that diagram. They are also arranged vertically so that material can flow from stage to stage by gravity. Other conveying is by pneumatics instead of bucket elevators. But the basic process is largely the same.

Evans’ trouble enforcing his patents will sound very familiar to anyone trying to do so today. All a patent has ever done here is give you the privilege of suing infringers. Especially as here where the crux of the invention is largely how common components are arranged. The nature of manufacturing and transportation then meant that the parts for these mills would have been constructed on site. It’s one thing to try to enforce a patent against another manufacturer and another to have to try to police every itinerant mill wright and smith, traveling around building mills. In the end, Evans had a good idea, once he had built a mill based on that, it was out there and there doesn’t seem to be any sort of bottleneck to keep every tom, dick or harry from taking and running with it.

This invention is subtly different from the developments taking place in England with textiles. While both were about reducing human labor, the issue in England was more the cost of that labor where in America, it was much more about a shortage of labor generally. The English textile industry was much more concentrated geographically and every aspect was more developed, not least patent enforcement. Famously, they tried to keep the spinning jenny secret by prohibiting emigration of mechanics that could replicate it and failed.

Even prior to the Evans improved mill, the use of waterpower for milling represented a huge improvement over the older ways. Circa 65 bc, the poet Antipater heralded the mill driven by the vertical water wheel:

Cease from grinding, ye women who toil at the mill

Sleep late, even if the crowing cocks announce the dawn

For Demeter has ordered the Nymphs to perform the work of your hands

And they, leaping down on the top of the wheel, turn its axle which

With its revolving spokes, turns the heavy concave Nisyrian millstones

Learning to feast on the products of Demeter without labour

Evan’s mill would have been a good deal more expensive and required a lot more skilled labor in the form of mill wrights, joiners and carpenters than an old style mill. Something that doesn’t figure in a lot of modern history books is that America was starved for circulating currency.

This was first a product of British mercantilism which monopolized trade with America such that American exports were exchanged for British goods with the transaction occurring entirely on that side of the Atlantic. It was one major provocation of the Revolution. Well into the 19th century, circulating coins included a random assortment of English, Spanish and other foreign coins, especially on the frontier. In the era of hard money, the absence of silver and gold mines east of the Rocky Mountains was a serious handicap to the American experiment.

I’m pretty sure that the miller was usually paid with a portion of the grain, so the decision to build one of these mills would also mean that upfront cost was being traded for future cost that would have been paid by ongoing operations. This is a pretty common scenario today with ubiquitous credit but would likely have been more complicated then.

The industrial revolution was enabled as much by business advancements, especially ways of raising money, as advances in technology