I have written in my columns on the end of WW2 in the Pacific about institutional or personally motivated false narratives, hagiography narratives, forgotten via classification narratives and forgotten via extinct organization narratives. Today’s column is revisiting the theme of how generational changes in every day technology make it almost impossible to understand what the World War II (WW2) generation is telling us about it’s times without a lot of research. Recent books on the like John Prados’ “ISLANDS OF DESTINY: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun” and James D. Hornesfischer’s “NEPTUNES INFERNO: The US Navy at Guadalcanal” focus in the importance of intelligence and the “learning by dying” use of Radar in the Solomons Campaign. Both are cracking good reads and can teach you a lot about that period. Yet they are both missing some very important, generationally specific, professional reasons that the US Navy did so poorly at night combat in the Solomons. These reasons have to do with a transition of technology and how that technology was tied into a military service’s training and promotion policies.

WW2 saw a huge paradigm shift in the US Navy from battleships to aircraft carriers and from surface warship officers, AKA the Black Shoe wearing “Gun Club,” to naval aviators or the Brown Shoe wearing “Airdales.” Most people see this as an abrupt Pearl Harbor related shift. To some extent that was true, but there is an additional “Detailed Reality” hiding behind this shift that US Army officers familiar with both the 4th Infantry Division Task Force XXI experiments in 1997 and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq will understand all too well. Naval officers in 1942-1945, just like Army officers in 1997-2003 were facing a complete change in their basic mode of communications that were utterly against their professional training, in the heat of combat. Navy officers in 1942-1945 were going from a visual communications with flag semaphore and blinking coded signal lamps on high ship bridges to a radio voice and radar screen in a “Combat Information Center” (CIC) hidden below decks. US Army officers, on the other hand, in 1997-2003 were switching from a radio-audio and paper map battlefield view to digital electronic screens. Both switches of communications caused cognitive dissonance driven poor decisions by their users. However, the difference in final results was driven by the training incentives built into these respective military services promotion policies.

During the “cultural change in combat” by the US Navy in 1942-45, this played out as the naval aviators, the “Brown Shoes,” displaced the battleship officers, the “Black Shoes,” as much because the latter were visual communications oriented as due to their being on battleships rather than aircraft carriers. Naval aviators could not function without radio, and later radar, coordinating and directing naval air power to accomplish it’s mission. Radio and radar were the immediate future of naval combat and naval aviators understood it far better than the “Gun Club.” In a real sense Pearl Harbor on Dec 7, 1941 was an extension of the Summer 1940 Battle of Britain, underlining it’s lessons on radio and radar directed air defense, at the expense of the Gun Club’s interwar visual communications based fighting doctrine.

Interwar US Navy Doctrine

The “Gun Club,” unlike the “Brown Shoes” was an heir to a visual communications tradition centuries in length and had spent the 1920’s and 1930’s “Refighting Jutland” incorporating radio plus better and better air support. The lessons that the “Black Shoes” learned from Jutland were the following:

1. The need for a uniform fleet doctrine locking all naval forces into a battleship centered decisive naval engagement doctrine and,

2. The need to utterly control and minimize radio communications to deny the enemy the kind of direction finding and code breaking intelligence the British Royal Navy gained on the German High Seas fleet at Jutland.

According to the book “BATTLELINE: The United States Navy 1919-1939,” this “Black Shoe” fleet doctrine called for a scouting phase with an 8-inch (203mm) gun heavy cruisers (CA) scouting line, a “screen fight” phase where friendly destroyers (DD) broke through to hit enemy capital ships with torpedoes while friendly 6-inch (152mm) gun light cruisers (CL) either supported such actions or prevented similar ones by the enemy by smothering DD’s with 6-inch shells. Then, finally, a decisive clash of battle lines which was followed by a vigorous screen pursuit of crippled capital ships or a organized disengagement to cover crippled American battleships. In these exercises friendly aircraft carriers (CV) eventually displaced not only the CA’s visual line scouting role, but also much of the DD and CL screen role in guarding and pursuing during the day in late 1930’s exercises. This resulted in a ranging CV plus CA task force stalking from behind the battle line, dashing out to strike, and retiring behind the big guns as needed.

Gun Club Training and Promotion Incentives

Tight budgets meant there was no training of American cruiser or destroyer flotillas in the kind of independent actions seen in the Solomons, and even if it had, night time training required more radio communications than the “Gun Club” was willing to use for fear of direction finding and code breaking by the enemy.

According to James Dunnigan and Al Nofi’s “VICTORY AT SEA,” there was also an additional factor stemming from US Navy promotion incentives. Gunnery scores on destroyer, cruiser and battleship live fire exercises was how “Black Shoe” Commanders got promoted to Captains and Captains got promoted to Admiral. This drove the Navy to make gunnery as “Fair” as possible at the expense of realistic training. Every time there was a choice between realism in gunnery training and “fairness” for promotion’s sake. Realism lost. By the end of the 1930’s battleships were firing in daylight, in good weather, in as smooth as glass calm seas as could be predicted by naval weather forecasters. This left the “Gun Club” part of the US Navy command structure with some very unrealistic professional expectations versus the chaotic reality of night time combat in the Solomons.

This was ultimately played out on November 13, 1942 when — after an earlier cruiser force victory by the radar and hard night training oriented “gunslinger” Rear Admiral Norman Scott — Scott was displaced in command by the less experienced, but senior by date of promotion, Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan. Callaghan’s first mistake was to put his flag on the USS San Francisco, an 8-inch gun heavy cruiser he had commanded previously. It was a much more powerful in daylight unit, but it was radar-less and ill equipped to command at night. Especially compared to the smaller, newer, light cruisers Helena, Atlanta and Juneau of his force, ships that had the latest radars and radios. Then Callaghan lead Scott’s former command, with Scott on one of the other ships, to the naval equivalent of bayonet range with two Japanese battleships. This mistake was followed by a series of confusing orders from his flagship including;

1. Directions to cease fire,

2. Directions to fire at the “big ones,” and

3. That odd numbered ships should fire to port and even numbered ships fire to starboard – – failing to take into account the actual position of the various ships in relation to the enemy.

Callaghan’s professional instincts, trained by a career in the interwar visual communications and “perfect condition” gunnery US Navy betrayed him and his men, killing him, RADM Scott, and hundreds more U.S. Navy sailors besides.

Cognitive Dissonance in Combat, the Navy and the NTC

The reason I am writing this column is I recognized in Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan’s performance a very similar performance that happened 52 years later at Ft. Irwin California, by commander of the 4th infantry Division’s first “Army XXI” digital brigade in its rotation through the National Training Center (NTC) in 1997. I wrote the following in my Winds of Change column titled “Network Force II” on March 26, 2004:

The Colonel running the digital brigade literally turned off/ignored all of his visual/graphical displays of his unit locations and listened to his radio chatter instead to form his mental picture of the battlefield. The displays were not agreeing with the mental picture this Colonel had of the battlefield from the radio chatter, so he ignored it.

.

It turned out that the prototype Blue Force Tracker was right and his radio chatter mental picture was wrong. The After action report made that one clear, yet the professional training of 15 years made this combat leader ignore what he was seeing in favor of the familiar.

Both RADM Calliaghan and this brigade commander made bad decisions because they were forced to use completely new communications paradigm with an old communications professional training and background. The primary difference between the two examples was that this brigade commander didn’t get anyone killed. The US Army’s NTC was, and remains today, the exact opposite of the US Navy’s 1919-to-1941 training. The NTC is all about throwing a much chaos at U.S Army commanders as the very professional opposing force or “OPFOR” can think of. Dealing well with chaos gets promotions in the US Army, not “Fair” gunnery scores.

.

This difference showed up in the further battles of the Guadalcanal, Central and Northern Solomons campaigns, like the Battle of Tassafaronga, sometimes referred to as the Fourth Battle of Savo Island, where four American cruisers were torpedoed. Again and again, new “Black Shoe” commanders rotated in to learn the same lessons in lost ships and blood.

By way of contrast in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the US Army was better able to shift communications paradigms due to training and the NTC institutional mindset according to this passage from the March 22, 2004 issue of Federal Computer Week:

“How much of a difference did Blue Force Tracking make in Iraq? One simply has to ask Army Lt. Col. John Charlton. On March 17, 2003, two days before the start of the war in Iraq, Charlton and his M2A3 Bradley crew meticulously cut and pasted laminated maps inside their 35-ton armored personnel carrier. Before the war, the Army quickly trained 3rd Infantry Division soldiers how to use Blue Force Tracking. However, they did not feel confident using the computer, so they didn’t turn it on when crossing into Iraq on their first mission.

.“What I should have spent the entire time focusing on was the small screen

attached to my door,” Charlton said after the war. “It had been accurately tracking

my location as well as the location of my key leaders and adjacent units the whole

time.”

.

But four days into battle, amid the Iraqi sandstorms, the Bradley crew finally turned

on Blue Force Tracking. The computer’s imagery and Global Positioning System

capabilities let them use Blue Force Tracking similar to how pilots use instruments

to fly in bad weather.

.

“The experience of being forced to use and rely on Blue Force Tracking during a

combat mission under impossible weather conditions completed my conversion to

digital battle command,” said Charlton, commander of 1-15 Infantry, 3rd Infantry

Division, in Army documents.”

Now you know a “detailed reality” of the WW2 Generation our modern technology makes hard to understand…and the subject of how this visual communications style affected inter -service and intra-service communications in the Pacific War will be in future History Friday columns.

Notes and Sources:

.

1) James Dunnigan and Al Nofi, “VICTORY AT SEA: World War II in the Pacific,” William Morrow, copyright 1995, ISBN 978-0-688-05290-4

http://www.amazon.com/Victory-Sea-World-War-Pacific/dp/0688149472

.

2) Thomas C. Hone and Trent Hone, BATTLELINE: The United States Navy 1919-1939, copyright 2006, Naval Institute Press, ISBN-13: 978-1591143789

http://www.amazon.com/Battle-Line-United-States-1919-1939/dp/1591143780

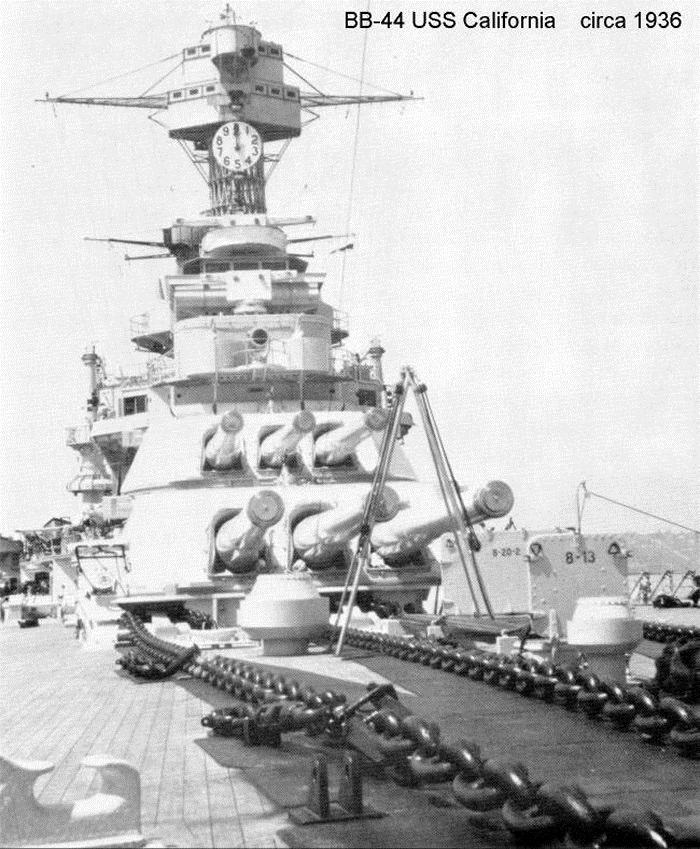

See pages 68, 69, 74, and 75 which have photos of Range clocks on Old BB’s in the 1920’s. This book explains in detail interwar US naval doctrine glossed over above.

.

3) James D. Hornesfischer, NEPTUNES INFERNO: The US Navy at Guadalcanal, Bantam books, Copyright 2011, ISBN978-0-553-80670-0

http://www.amazon.com/NEPTUNES-INFERNO-Hornfischer-Hardcover-Neptunes/dp/B004JC06OU/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390532577&sr=1-2&keywords=NEPTUNES+INFERNO%3A+The+US+Navy+at+Guadalcanal

Hornesfischer goes into detail and the hard and realistic training Rear Admiral Norman Scott put US Navy surface units after the disaster of the first Battle of Savo Island, and how Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan, threw it all away with his obsolete visual battle professional instincts. Explaining the later battleship action off Savo island, Hornesfischer tells how USS Washington and Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr. showed the way to the new age of “Radar gunslingers.” An age that would reach it’s apex during the Battle of Surigao Strait 24-26 October 1944. When the radar gunfire equipped old battleship gunline saw off two Japanese battleships with virtually no losses.

.

4) J.D. Ladd, ASSAULT FROM THE SEA 1939-1945: The Craft, The Landings, The Men, copyright 1976, Hippocrene Books Inc, ISBN: 0-88254-392-X

http://www.amazon.com/Assault-Sea-1939-45-Craft-Landings/dp/088254392X/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390532646&sr=1-2&keywords=ASSAULT+FROM+THE+SEA+1939-1945%3A+The+Craft%2C+The+Landings%2C+The+Men

.

5) John Prados, ISLANDS OF DESTINY: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun, Copyright 2012, NAL Caliber, ISBN: 978-0-451-23804-7

http://www.amazon.com/Islands-Destiny-Solomons-Campaign-Hardcover/dp/B00EQSPQI8/ref=sr_1_fkmr0_3?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390532711&sr=1-3-fkmr0&keywords=ISLANDS+OF+DESTINY%3A+The+Solomons+Campaign+and+the+Eclipse+of+the+Rising+Sun

Prodos also covers the Battleship action off Savo island but also covers the further Central and Northern Solomons naval actions where brand new “Gun Club” commanders of thrown together task forces had to learn the same lessons over and over again at the price of lost ships and dead crews.

.

6) Trent Telenko, The Networked Force II, March 26, 2004

http://windsofchange.net/archives/004759.html

FYI . . .

http://news.usni.org/2013/12/31/f-35c-will-eyes-ears-fleet

I have a number of well informed doubts about the F-35.

See:

http://www.ausairpower.net/jsf.html

http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2013-05/rise-missile-carriers

Written by the son of Science Fiction writer Jerry Pournelle. Looks like he dove right into the current ferment of the Navy on what the future of naval combat will be like.

Very informative, thank-you. The training and experience is vital, learn to use the tools, the training and experience should do this as well as provide training to function when the tools fail (and these do!).

One of those links has an interesting comparison of the JSF with the F 105 Thunderchief.

This is a fantastic article per usual. One slight tweak is that i think it is “Solomon” not “Soloman”

My dad was on the Frisco (though not till much later). In later life he was editor of the USS San Francisco (CA-38) Association Newsletter, which was published quarterly, and which I assisted him with (me being a computer geek and him definitely NOT being one.)

That detail about the training and experience differences between Callaghan and Scott is something I’ve never heard. Thanks! I’m going to run this by my dad and see what he thinks… thought at this point his Alzeheimer’s is affecting a lot more than just his short-term memory–his reading and correspondence about Naval History is pretty much completely gone now.

Carl, you are right.

It should be fixed now.

>>That detail about the training and experience differences

>>between Callaghan and Scott is something I’ve never heard.

This is implicit in even Adm. Samuel Elliot Morrison’s institutional histories.

See his footnote 21 on page 109 of “BREAKING THE BISMARKS BARRIER 22 July 1942 – 1 May 1944.” In it he “thumbnail outlines” the development of Radar CIC’s as background to Adm Merrill’s sinking of a pair of Japanese destroyers the night of 6 March 1943.

Also compare Adm. Morrison’s description of the heavy and orderly radio communication between the four light cruisers of Adm Merrill’s force at the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on 2 Nov 1943 — seen pages 305 – 318 of “BREAKING THE BISMARKS BARRIER 22 July 1942 – 1 May 1944.” and page 313 specifically — compared to the confused orders and radio communications of Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan at Savo Island I laid out above.

The reason I wrote of the same events differently than either Prados or Hornesfischer is that I am using a different historical methodology to look at the same events.

One of several I am developing with this column.

One of those links has an interesting comparison of the JSF with the F 105 Thunderchief.

To understand aircraft like the F-105, you have to put yourself into the mindset of the mid-fifties military. From their perspective, conventional war was a thing of the past. All future war would be ‘atomic’ wars. That was a completely wrong prognosis and the price for the weapons and training decisions that resulted from that outlook were paid all through the Vietnam War.

The F-105 was designed to fly fast to a target, drop a nuke at low level, and fly back to rearm. It suffered badly from immature jet engine technology and was woefully underpowered. A superficial resemblance of the nose and engine intakes between the F-105 and F-35 is meaningless, except that they were both aerodynamically designed to fly in the high transonic region.

The F-35 is getting rave reviews from the military and test pilots who’ve flown it. Here’s a test pilot talking about the F-35:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJVJsN4WDXQ&list=PLqa9423Jd9Mo9_5Wo_sF_gor3SN4uEVq7

IMO this is unfair to Callaghan personally. He’d have had to entirely step outside his training and experience to give command to Scott. Furthermore the San Francisco was Scott’s own flagship in the Battle of Cape Esperance. It was normal for Callaghan to keep the same flagship.

Plus Scott’s trained force at Cape Esperance had lost two of its four cruisers sent home for damage, and one destroyer sunk. The American force for Guadalcanal I was largely a scratch one built on what was left of Scott’s force.

The crucial pre-battle decision was Callaghan’s – to get in really close where the armor of the Japanese battlecruisers could be penetrated by his heavy cruisers’ 8” guns, and that is in fact what won the battle. The Hiei was riddled by 8” shells penetrating its armor – at least a half dozen each from both American heavy cruisers. The San Francisco wrecked the Hiei’s steering gear – this was the critical event of the battle as Marine land-based air sank the crippled Hiei the next day. The Hiei blew the crap out of the San Francisco’s bridge and killed Callaghan.

What was Callaghan’s fault was compromise. He knew very well that he was up against two Japanese battlecruisers and had little chance of success, or even survival. He personally expected to die, and he should have factored that into his planning given his decision to get in really close, i.e., he should have planned for losing control.

Close-in at night means a melee action. Callaghan knew he had a scratch force going up against a trained superior force. Getting in close and going melee helps an inferior scratch force overcome a more cohesive & powerful one.

Callaghan fought the way he had been trained to fight using forces unfamiliar to him, except for the San Francisco which he had previously been captain of. He made mistakes and died. But he won.

>>IMO this is unfair to Callaghan personally. He’d have had to entirely

>>step outside his training and experience to give command to Scott.

Tom,

Granted that Callaghan’s mission was to block the Japanese bombardment of Henderson by any means necessary, to include the sacrifice of his force.

Granted that the US Navy was going to take heavy casualties achieving that mission goal regardeless of who was in charge.

However, Callaghan’s first mistake was not _listening_ to RAdm Scott. Callaghan did not have to give up command to Scott to organize his force to use radar to best advantage.

Scott was the radar expert, he was the man on the scene who analyzed the previous night defeat and worked to make the men, equipment and radar based doctrine work for the next go, and Callaghan’s formation showed he ignored Scott.

Callaghan’s second mistake was to pick USS San Francisco, a visual unit, to command a night fight.

This third mistake was is issue order, counter-order, dis-order trying to fight a night fight like a day fight.

The second and third mistakes were of the order that the 4th ID Brigade commander made — being on the wrong side of professional paradigm shift — that first mistake was all Callaghan’s.

Trent, Callaghan did have to give up command to use Scott to best advantage, i.e., co-locate them both on the same ship. That would have been contrary to naval doctrine. Plus the San Francisco was Scott’s own flagship. He shifted to the newly arrived Atlanta after Scott arrived.

It was the light cruiser Helena, newer than the San Francisco but older than the Atlanta and Juneau, which had the best combination of signals, radar and flag space. Neither admiral considered it. The San Francisco was their best fighting ship with the most flag space.

Look again at Scott’s own choice of flagship.

The real Radar expert was Willis Lee who had been involved with it for years and is said to have been able to work on it as a technician. Lee fought the second battle with the Washington alone. The story. It gets a little hysterical at times.

“Washington was now the only intact ship left in the force. In fact, at that moment Washington was the entire U.S. Pacific Fleet. She was the only barrier between Kondo’s ships and Guadalcanal. If this one ship did not stop 14 Japanese ships right then and there, America might lose the war.”

The South Dakota was useless and got in the way several times. Captain Thomas L Gatch apparently was relieved after she reached New York. I am unable to see any further assignments for him. It was the chief engineer who closed the circuit breakers before the battle and blinded the ship. It was renowned in the Navy at the time for being a hard luck ship.

A fun web site dedicated to the Atlanta. Underwater photography.

One of the South Dakota crewmen was the incredible Calvin Graham.

Capt. Gatch was a lawyer by training and after he was detached from the South Dakota, he served as the 16th Judge Advocate General (JAG) of the USN from 1943-45. The immediate cause of his relief of command was due to wounds suffered in the action at Guadalcanal, for which wounds he was hospitalized on return to the US. Gatch was not a hard-core black shoe clubber since many of his prewar assignments were also attached to the JAG corps.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Leigh_Gatch

The South Dakota’s career also had its highlights. Just prior to the naval battles of Guadalcanal, the SoDak was credited with shooting down 26 Japanese aircraft at the Battle of the Santa Cruz islands in October 1942.

Capt. Gatch was awarded two Navy Crosses for his service: the first for Santa Cruz and the second for the Guadalcanal action.

Tom,

I was very much aware of that when I wrote my last reply.

The issue was one of the battle plan Callaghan ignored, via wikipedia —

Scott crafted a simple battle plan for the expected engagement. His ships would steam in column with his destroyers at the front and rear of his cruiser column, searching across a 300 degree arc with SG surface radar in an effort to gain positional advantage on the approaching enemy force. The destroyers were to illuminate any targets with searchlights and discharge torpedoes while the cruisers were to open fire at any available targets without awaiting orders. The cruiser’s float aircraft, launched in advance, were to find and illuminate the Japanese warships with flares. Although Helena and Boise carried the new, greatly improved SG radar, Scott chose San Francisco as his flagship.[16]

And the radio-communications performance of USS San Francisco in the previous battle, also from Wikipedia —

At 23:00, the San Francisco aircraft spotted Jojima’s force off Guadalcanal and reported it to Scott. Scott, believing that more Japanese ships were likely still on the way, continued his course towards the west side of Savo Island. At 23:33, Scott ordered his column to turn towards the southwest to a heading of 230°. All of Scott’s ships understood the order as a column movement except Scott’s own ship, San Francisco. As the three lead U.S. destroyers executed the column movement, San Francisco turned simultaneously. Boise””following immediately behind””followed San Francisco, thereby throwing the three van destroyers out of formation.[20]

Scott should have been on either the USS Helina or USS Boise (Both Brooklyn class CL’s) for the reasons you stated.

That does not relieve Callaghan of the “I’m in charge, we do it my way” change to Scott’s radar based battle plan, Callaghan’s ignoring the USS San Francisco’s communication problem in the previous battle and his insistance on close control where none was possible at night.

Understanding the inability to do close control was something Scott’s radar based night fighting plan took into account.

Adopting Scott’s Battle of Cape Esperance plan with the targeting priotity of “Get close and the big ones” would have covered the mission needs of this battle just fine without the confusion that happened.

Instead Callaghan insisted on fighting a close control visual gunfight at night without regard to his own DD torpedos.

Adm. Callaghan had served as FDR’s naval aide prior to the war and was reportedly very popular with the president and members of his staff. FDR released Callaghan from his duties at the White House to take command of the San Francisco several months before Pearl Harbor. Callaghan might have based his choice of flagship due to the fact he had served recently on this ship and knew her crew.

“A superficial resemblance of the nose and engine intakes between the F-105 and F-35 is meaningless, except that they were both aerodynamically designed to fly in the high transonic region.”

The link was to an evaluation by the Australian services who have some questions about the survivability of the F 35 without escort in a war setting. That was the comparison with the F 105 that had similar issues. Appearance had nothing to do with it.

The resulting F-105 series was a fighter which is remarkably close to the current JSF in most important cardinal parameters.

Both the F-105 and JSF are large single seat single engine strike fighters, using the most powerful engine of the era (J75 vs F135/F136), with empty weights in the 27,000 lb class, and wingspans almost identical at 35 feet. Both carry internal weapon bays, and multiple external hardpoints for drop tanks and weapons. Both were intended to achieve combat radii in the 400 nautical mile class. Neither have by the standards of their respective periods high thrust/weight ratio or energy manoeuvre capability, favoured for air superiority fighters and interceptors.

John Pierce,

I don’t doubt that was the reason behind Adm. Callaghan’s choice of the USS San Francisco.

It was still a bad choice.

One compounded by the USS San Francisco’s earlier communication failure with Adm Scott.

I think there was also a reluctance on Adm. Callaghan’s part to make his flagship one of the AA cruisers like the Atlanta or one of the regular cruisers like the Helena. The San Francisco was a heavy cruiser with 8″ main battery and more protection than the other ships. Perhaps he felt that the longer range of the 8″ gun would allow him to engage the Japanese forces before the smaller ships with their 5″ and 6″ main batteries.

Obviously, it takes time to integrate a new tactical weapon like radar into existing combat doctrine. The use of radar also forced changes on the way naval battles were fought, such as the development of combat information centers (CIC) on board ship, so that the tactical information gleaned by radar could be collated to provide a picture of the disposition of enemy forces, something heretofore which was unavailable during naval combat. The CIC was a similar concept to the Fighter Control system which the British developed and used brilliantly during the German air campaign against the Home Isles in 1940-41. The CIC would be used not only for surface actions, but also in the carrier campaigns later in the Pacific war. It remains a key component of naval air warfare today.

During the early part of the engagement, it also appears that San Francisco mistook Atlanta for a Japanese vessel and opened fire on her. It is thought that Admiral Scott and his staff were tragically killed by friendly fire rather than the Japanese.

:… it also appears that San Francisco mistook Atlanta for a Japanese vessel and opened fire on her.”

I love that!

Trent, sorry I missed your earlier comment on the F 35.

Michael,

Aussie Air Power is a well know, if not notorious, site in the aerodynamics community. Their opposition to the F-35 is famous. In the end, you have to decide if they know more about what will work or if the engineers at Lockheed and the pilots who had lots of input to the design know more. You have to trust one or the other in the end.

Briefly, the thinking behind the F-35 was this:

You cannot out turn and out burn new generation air-to-air missiles. They have much greater acceleration and greater top speed than you generate in your aircraft.

New generation phased array radars with low probability of intercept (LPI) steerable beams make big bright targets out of current (Gen 4+) aircraft.

Dog fights rarely occur. They were the norm through the Korean War, less so in Vietnam, rare since then.

Flying at Mach 1+ rarely occurs. It burns too much fuel unless you’re extremely high where the air is very thin. The time an average F-15 spends at Mach 1+ over its life is measured in minutes.

Moreover, after the first day or two, fighter-bomber aircraft spend most of their time in ground attack or patrol.

The primary design goals of the F-35 were:

Make it stealthy. If you can’t track it, you can’t lock weapons on it. First look gets first shot gets the kill. That’s the plan, anyhow.

Make it maneuverable enough to defend itself, but not more so, since that limits it ability to do other things, like carry fuel and ordnance. According to the pilots who’ve flown it, it handles like an F-18, out accelerates an F-16, and has more range on internal fuel than either.

Thrust-to-weight (T/W) and wing loading do not compare between third and fifth generation aircraft. For starters, the F-35 carries its combat fuel and weapons internally. Hang a bunch of weapons and fuel tanks on even a 4th generation aircraft like an F-16 (a warload) and it’s numbers and handling are completely different than in stripped down “airshow” configuration. The F-35’s handling doesn’t change hardly at all. Pilots report it handles the same loaded or unloaded. In addition, the F-35, like the F-22, is a lifting body. Wings are only part of its lift.

After stealth – and the DoD reports they are “very, very pleased” with its RCS – the biggest advance in the F-35 are the avionics. Just for example, they have a revolutionary imaging system built into the aircraft, the Distributed Aperture System (DAS). Comprising six IR cameras, they provide 360 degree coverage and project it into the pilots visor. The pilot can look, literally, right between his legs and see what’s beneath him or see in any direction he/she chooses. DAS also tracks all aircraft and targets in the vicinity and color codes them by what it identifies them to be. It goes on and on.

I had my doubts about the program becoming another TFX fiasco, but Lockheed/Northrop/Boeing (all are involved, LM is the prime) seemed to have pulled it off. The test pilots and warfighters who’ve flown it are really enthusiastic about this machine and its capabilities. Bill Beesely, the F-22 chief test pilot and the F-35 chief test pilot, said if were going to an airshow, he’d take a sleek and beautiful stripped down F-16. If he were going to war, no question, he’d take an F-35. I have to trust his judgement on this.

Michael, just curious, about how many F16s can be built for the cost of one F-35?

Interesting question. It depends on when you buy. Production is just really beginning, and the cost per lot depend on how many get ordered. Right now, I believe DoD is paying about $100 million each in low rate production, minus engine, as always. The end goal is to get the F-35A (conventional USAF model) to around $60 million each in 2000 dollars. The USMC STOVL (F-35B) and Navy (F-35C) models are more expensive, as they’re more complex, by another $8-$10 million each. So far, the pricing is following the numbers ordered versus price-each slope that was predicted pretty well. A current buy of F–16’s is around $15-$20 million each. But that’s before you hang on lots of expensive warfighting gear too. All of which is included in the F-35 for all three models (except the gun, which the Navy declined).

A more interesting question: How many P-58 Mustangs can you buy for the cost of an F-16? I’m not being facetious. I was one who supported building modern prop driven attack aircraft for use in low intensity or counter-insurgency conflicts. Lots of bang for your buck, so to speak. The mix would be F-22(Hi)/F-35(Lo)/COIN. On the other hand, allies are replacing aircraft as well, and they need a one size fits all combat aircraft. The F-35 does well in that role.

Michael Hiteshew,

The latest round of DOTE and other governance reports for the F-35 stink.

An “ideal” F-35 — one which met or exceeded grossly the 2001 specs — could have been a new, stealthy Thud. Instead the latest DTOE says the F-35 will have A-7D class range/payload performance, F-15 class weight, and F-22 class pricing…without the F-22’s level of stealth or non-afterburning supercruise.

Trent

I hardly know where to start with that.

If I recall correctly, the design concept goals were that that F-35 have the range and payload of an A-7 with F-16 like handling and maneuverability. So, sounds pretty much like mission accomplished there, although it has F-18 handling instead.

An F-22 costs 50% more, and the F-35 is still in LRIP. In full rate production the price is scheduled to drop another 30%. That will make it comparable in price to an F-18E and much cheaper than a Eurofighter.

>>without the F-22”²s level of stealth

What is the radar cross section (RCS) of either aircraft? What is your source? As far as I know, the RCS of both aircraft is classified. How can you possibly know whether it has the F-22’s level of stealth or not?

>>or non-afterburning supercruise

That F-35 was not designed to supercruise. It doesn’t fly in low earth orbit or land on water either. But those weren’t part of the design specification. However, the F-35B does make short take offs, hover, and land vertically; and the F-35C is intended to land on a carrier and operate in a salt air environment. The F-22 doesn’t do either of those things.

The F 105, for all its weaknesses, was a good solid airplane. Read “When Thunder Rolled” for a nice account of it in Vietnam.

I suspect we are seeing the last manned aircraft in a role like that planned for either the F 35 or F 22. I examined a kid today who is joining the Air Force with very high AQFT scores to fly drones. He knows exactly what he wants to do and probably will do it. He is prior service joining the ANG and was stationed at the AF Academy and we laughed about all the cadets who will never get to fly. Join the Army and fly.

Personally I think we should reopen the B 52 production line and the A 10 line.

Michael, what happened to the B 58 Hustler ? Was it a single purpose plane that was outmoded when it was new ? I’ve always wondered.

Interesting sidelight on the B 58.

“Singer John Denver’s father, Colonel Henry J. Deutschendorf, Sr., USAF, held several speed records as a B-58 pilot.”

The father was a much better pilot. Some of the B 58 records still stand.

” How many P-58 Mustangs can you buy for the cost of an F-16? I’m not being facetious. ”

Yeah, if I recall correctly, the late Mustangs weren’t that far behind early jet fighters in overall performance. The 2014-P58/1946-P58 comparison might be analogous to a 2014-Ford-sedan/1946-Ford-sedan comparison WRT to technology. And the relative cost for building that machine has been greatly reduced.

>>Personally I think we should reopen the B 52 production line and the A 10 line.

I think you could more easily convert and qualify a C-17 into a fairly effective, modern, heavy bomber with intercontinental range. The aircraft is already mil-qualified. And I couldn’t agree more on the A10. Tough, cheap, extremely effective machine. Put some ‘off the shelf’ modern avionics in it and keep everything else the same. Absolutely. Great idea. Why don’t they obvious things like this? My guess is that the HASC and SASC has been paid off not to.

>>Was it a single purpose plane that was outmoded when it was new? I’ve always wondered.

In a sense, yes. It’s mission was similar to the F-105. Fly fast to a target, drop a nuke, get home. The development of intercontinental range ballistic missiles put an end the B-58 and stopped the B-70 in its tracks. The B-58, besides being fast and beautiful, was also very expensive to buy and operate. They were more expensive than a B-52.

BTW, can you imagine the USA developing, producing and fielding all of these different bombers in just 20 years?

B-36 – 384

B-47 – 2,032

B-50 – 370

B-52 – 744

B-58 – 115

B-70 – 2 development

That is just dedicated bomber aircraft. That’s a new bomber about every three years.

“And I couldn’t agree more on the A10. Tough, cheap, extremely effective machine. Put some ‘off the shelf’ modern avionics in it and keep everything else the same. Absolutely. Great idea. ”

I think the AF has a “ground to mud” antipathy. GIve them to the Army.

On bombers, my father was a machinist on the B 36 when I was a kid. The movie “Strategic Air Commend” has a nice segment on a B 36 mission.

The B 50 was just a B 29 with newer engines. It wasn’t survivable in Korea.

The B 58 was a work of art.

My father-in-law walked up the engine intakes of a B 70 without having to stoop over.

Michael, what happened to the B 58 Hustler ? Was it a single purpose plane that was outmoded when it was new ? I’ve always wondered

The B-58 was retired when regular inspections and a couple of crashes revealed cracks in the fuselage. Metallurgy was not as advanced when it was designed and built in the late 1950’s, and the stress from the heatup and cooldown of continual supersonic flying wore them out. They were retired before they killed any more crews.

Yeah, if I recall correctly, the late Mustangs weren’t that far behind early jet fighters in overall performance.

The P-51H had a top speed of 487 mph, which was about 80-100 mph slower than the P-80 and ME-262. The last test version P-47 was the first prop plane to exceed 500 (505), but it never went into production. The P-82 Twin Mustang hit 480 also with Allison engines. If Merlins had been installed, it probably would have done 500 also.

Most of the remaining A-10’s were updated right at the turn of the century.

The B-58 Hustler was a plane which had a number of compromises in its design.

Although it is often billed as a supersonic bomber, the plane was designed only for a supersonic burst of speed over its target. Flying to and from the target was done sub-sonically. It also had a combat radius of about 1500 nautical miles, which meant it had to be based close to the theater of action.

Its delta wing meant it had a high landing speed, and it used special landing gear to accommodate this. It was tricky to fly (the pilots were all highly trained to master delta winged flight) and it had relatively high maintenance costs.

Because the internal volume of the airframe was limited (and reserved mainly for the crew and fuel), the actual bomb payload was carried on an external pod fitted below the fuselage. There was no room for conventional bombs, so the B-58 was exclusively used as a nuclear bomber, with no tactical application.

As designed in the 1950s, the B-58 was intended to operate at high altitude. When the Soviets developed viable surface-to-air missiles, the tactical doctrine of the USAF formulated in response was to bring the bombers down to low altitude, terrain-hugging mission profiles. The B-58 was entirely out of its element then, and it was only a matter of time until the USAF phased it out. Robert McNamara is usually given the credit for the chop. The B-58 was replaced by the FB-111, a plane which had a long and troubled development history itself.

How’s this for an air show? http://youtu.be/WmseXJ7DV4c

“How’s this for an air show? http://youtu.be/WmseXJ7DV4c”

Loved it. In 1959 I was working for Douglas on the Nike Hercules system. I was just thinking about medical school and took a night class in biology to see if I liked it.

The B 58 had a reputation as a crew killer, even with three escape pods. They lost 26 of them so it had a reputation like that of the Martin B 26.

“Indeed, the regularity of crashes by pilots training at MacDill Field””up to 15 in one 30-day period””led to the exaggerated catchphrase, “One a day in Tampa Bay.”[14] Apart from accidents occurring over land, 13 Marauders ditched in Tampa Bay in the 14 months between the first one on 5 August 1942 to the final one on 8 October 1943.[14]

B-26 crews gave the aircraft the nickname “Widowmaker”

At least the B 58 designation wasn’t given to another airplane, an insult to the Martin that I never understood.

“By the time the United States Air Force was created as an independent service separate from the Army in 1947, all Martin B-26s had been retired from US service. The Douglas A-26 Invader then assumed the B-26 designation.”

Michael – you like Aerospace – you would find this book interesting –

http://www.amazon.com/Flight-Testing-Edwards-Engineers-1946-1975/product-reviews/0971370206/ref=dp_top_cm_cr_acr_txt?showViewpoints=1

AFAIK it is only available at the Edwards Museum and Amazon

Quite a write up on the problems of the B58

Thanks, Bill. I ordered a copy.

My father-in-law worked at Hughes Aircraft. On my first date with his daughter, we were supposed to go out but, after he and I got talking, we wound up staying at their house and my girlfriend and her mother made dinner instead. I was the only boyfriend she brought home that he liked.

I knew about the U 2 in 1959 from guys who had worked on it. And we even knew how high it flew, information that didn’t come out for decades. He was head of PR for Hughes and knew everybody.

I’m now reading Simon Ramo’s book about the ICBM. And his charmed life, of course. TRW was almost next to the wind tunnel building where I worked at Douglas. I now drive by there once a week going to the military recruit center. Everything I knew is gone now. It’s huge aerospace center.

Put it on my Wish List. Looks interesting! Thanks Bill.