When airplanes first started to be used for serious transportation purposes, sometime after World War I, the problems involved with flight at night and in periods of low visibility became critical. Transcontinental airmail, for example, lost much of its theoretical speed advantage if the plane carrying the mail had to stop for the night. Gyroscopic flight instruments addressed the problem of controlling the airplane without outside visual references, but there remained the problem of navigation.

An experiment in 1921 demonstrated that airmail could be successfully flown coast-to-coast, including the overnight interval, with the aid of bonfires located along the route. The bonfires were soon displaced by a more permanent installation based on rotating beacons. The first lighted airway extended from Chicago to Cheyenne…the idea was that pilots of coast-to-coast flights could depart from either coast in early morning and reach the lighted segment before dusk. The airway system rapidly expanded to cover much of the country–by 1933, the Federal Airway System extended to 18,000 miles of lighted airways, encompassing 1,550 rotating beacons. The million-candlepower beacons were positioned every ten miles along the airway, and in clear weather were visible for 40 miles. Red or green course lights at each beacon flashed a Morse identifier so that the pilot could definitely identify his linear position on the airway.

Lighted airways solved the navigation problem very well on a clear night, but were of limited value in overcast weather or heavy participation. You might be able to see the beacons through thin cloud or light rain, but a thicker cloud layer, or heavy rain/snow, might leave you without navigational guidance.

The answer was found in radio technology. The four-course radio range transmitted signals at low frequency (below the AM broadcast band) in four quadrants. In two of the quadrants, the Morse letter N (dash dot) was transmitted continuously; in the other two quadrants, there was continuous transmission of the Morse A (dot dash.) The line where two quadrants met formed a course that a pilot could follow by listening to the signal in his headphones: if he was exactly “on the beam,” the A and the N would interlock to form a continuous tone; if he was to one side or the other, he would begin to hear the A or N code emerging.

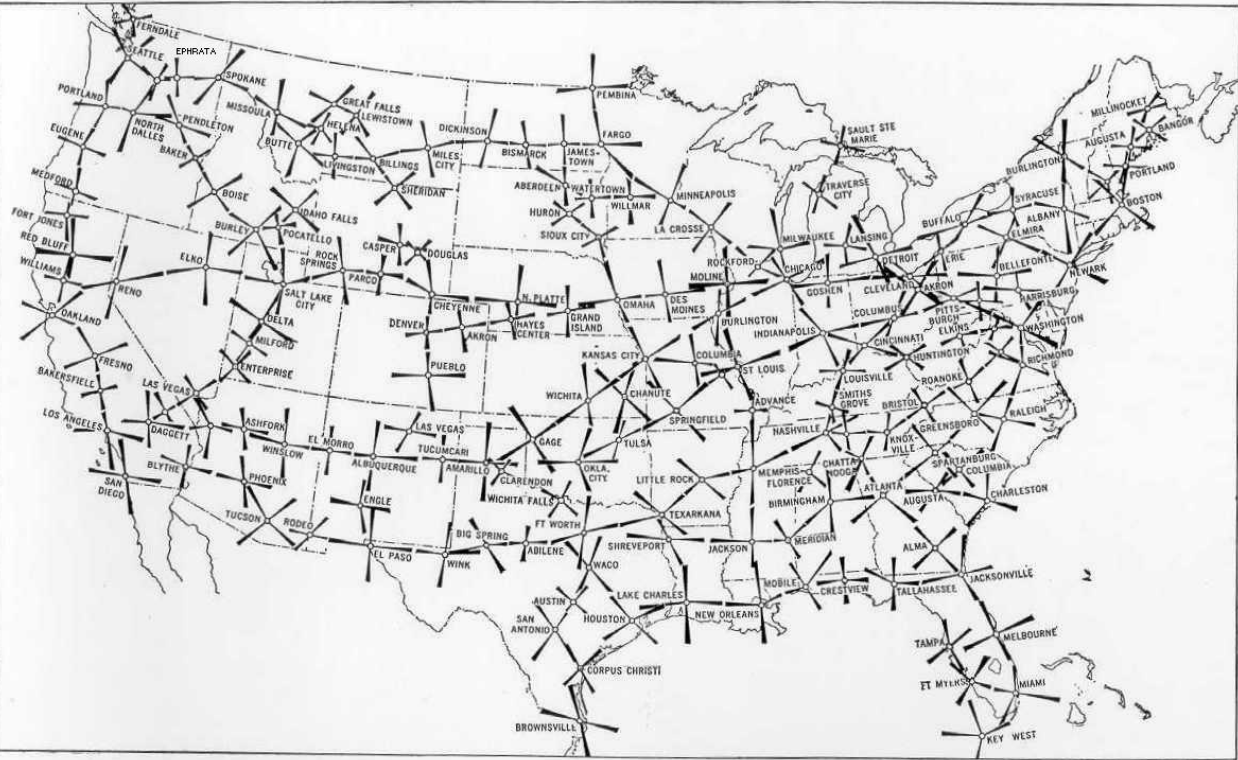

The radio range stations were located every 200 miles, and were overlaid on the lighted airways, the visual beacons of which continued to be maintained. The eventual extent of the radio-range airway system is shown in the map below. All that was required in the airplane was a simple AM radio with the proper frequency coverage.

The system made reliable scheduled flying a reality, but it did have some limitations. Old-time pilot Ernest Gann described one flight:

Beyond the cockpit windows, a few inches beyond your own nose and that of your DC-2’s, lies the night. Range signals are crisp, the air smooth enough to drink the stewardess’s lukewarm coffee without fear of spilling it…Matters are so nicely in hand you might even flip through a magazine while the copilot improves his instrument proficiency…

Suddenly you are aware the copilot is shifting unhappily in his seat. “I’ve lost the range. Nothing.”

You deposit the Saturday Evening Post in the aluminum bin which already holds the metal logbook and skid your headphones back in place…There are no signals of any kind or the rap of distance voices from anywhere in the night below. There is only a gentle hissing in your headphones as if some wag were playing a recording of ocean waves singing on a beach.

You reach for a switch above your head and flip on the landing lights. Suspicion confirmed. Out of the night trillions of white lines are landing toward your eyes. Snow. Apparently the finer the flakes the more effective. It has isolated you and all aboard from the nether world. The total effect suggests you might have become a passenger in Captain Nemo’s fancy submarine.

Gann continued the flight via dead reckoning, aided by rough cross-bearings on commercial broadcast stations, until the range became audible again.

The range could also be used for instrument approaches, as shown on this approach plate. Gann describes a range approach to Newark Airport in light blowing snow.:

The on-course signal is building very sharply. You turn the volume down to save your ears and estimate fifteen seconds to the cone…In the tight little world of professional flying there are in the whole nation less than a thousand pilots who fly instruments regularly, and fewer still who shoot 300-foot approaches in blowing snow at night. Therefore, when the peanut light glows to indicate the cone and the signal crescendos and almost immediately falls away to complete silence, it behooves you to fake a yawn…

The range signals are now reversed with the Ns and As changed sides. As you leave the station the signal volume diminishes as rapidly as it mounted. The marker light goes out. You have allowed your speed to drop off the 105…

Twenty seconds to go and 105 miles per hour, which is about as slow as you care to proceed until you break out underneath–if you do. Altitude 400 feet and still descending…

You halt the altimeter at 250 feet…and start counting.

“I have the perimeter lights.”

You glance out ahead and immediately flip on the landing lights. Two bright lozenges appear in the snow. They seem to be racing each other. It is all over and you have only cheated by fifty feet.

The perimeter lights slip past as you flare very slightly to make a wheel landing which is most pleasant and satisfying upon a cushion of snow. “Are we down?”

In the 1950s, a new electronic navigation technology was introduced: the Very-High Frequency Omnidirectional Range. Instead of the four courses of a classical radio range station, there are a theoretically-infinite number of courses to or from a VOR station. Each VOR ground station (there are about 1000 in the US) transmits an omnidirectional master signal and a highly directional signal that rotates 30 times a second: equipment in the aircraft compares the time relationship of the two signals. The pilots selects the desired course TO or FROM the station, and a pointer shows his position to the LEFT or RIGHT of that course line. The VOR system is much less sensitive to static and weather than was the radio range system, but it does suffer from line-of-sight range limitations. VOR has been the primary aeronavigation system in the US for decades, but it is expensive to operate all those ground stations, and the FAA is now selectively reducing their number, intending eventually to only maintain a limited system as backup for GPS.

It should be noted, though, that GPS signals are very weak by the time they reach the earth, and, hence, GPS is not difficult to jam. The military regularly conducts tests of GPS jamming systems, and some pilots have been surprised by failure of their GPS navigation systems after not carefully checking the NOTAMs (‘Notice to Air Missions’, until recently known as ‘Notices to Airmen’) In addition to VOR availability as a backup, many airliners now also carry inertial navigation systems, although these are subject of increasing drift errors over time if not reset to a known position.

The last visual airways beacons operated by the FAA were shut down by the early 1970s; however, there are still some beacons in western Montana which are operated by the state government. The radio range system was largely phased out in the 1960s, but a range segment in Alaska continued to operate until 1974. See the FAA’s photo album: building the airways.

The Ernest Gann excerpts are from his book Ernest K Gann’s Flying Circus.

I was reminded of this post by a new biography of Antoine de St-Exupery that I am currently reading: The Prince of the Skies, by Antonio Iturbe. In addition to St-Exupery’s literary work, his interaction with local tribesmen in North Africa, and his love affairs, the book extensively discusses the courageous work in reliable airmail service that was pioneered by St-Ex and his friends.

Another pretty good book on the beginnings of the Air Mail Service from the beginning is:

“Mavericks of the Sky: The First Daring Pilots of the U.S. Air Mail”

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004PYDNJC/ref=kinw_myk_ro_title

From back in the time when the Postal Service cared about delivering the mail. A disturbingly long list of fatalities. They often took off without more than a hope they could find a place to land before they ran out of gas.

The passages about St-Ex and his friends delivering mail over the Andes are pretty terrifying.

He had his close calls in the Sahara from, take your pick: weather, breakdowns, unfriendly tribesmen, often in various and novel combinations.

Nostalgia aside, I’d bet most pilots were happy to see the radio range system starting to be replaced by VORs. Listening to the range hour after hour, especially at times when there was severe static, must eventually damaged one’s hearing.

I am writing about this in my current work in progress, a history of the airlift to China in WWII. I even have artwork commissioned to show how it could be used for navigation.

It was the only electronic navaid then available, and initially, did not cover the whole route. (It was 500+ miles and the effective range of LF/MF Radio Range was no more than 100 miles.) They put in a station in Ft Hertz in northern Burma in 1943 or so. If you could not hear it during the midpoint it meant you were too far north, and flying over the Himalayas instead of their foothills. That meant you had an excellent chance of encountering a cloud formation known as cumuli-granite.

Seawriter: “… a history of the airlift to China in WWII.”

In case you had not come across it, David F. recommended the autobiography “Father, Son & Co” by Thomas Watson Jr. of IBM fame. During WWII, Watson was a pilot — and made one flight as a co-pilot over the Hump. His recollection of that trip, and of the attitude of the pilots who made the flight every day, is quite interesting.

Gavin…read the Watson autobiography and even wrote a review of it:

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/69269.html

I think flying, and especially flying overseas with Air Corps, really made Watson, in that it got him out for a while from his father’s rather dominating influence. He mentioned that as an adolescent he suffered from severe depression, and though he didn’t say so, I suspect that it was partly a matter of feeling that his life was pre-planned in advance.

David — yes, thanks to your earlier recommendation, I acquired a copy of Watson’s autobiography and enjoyed reading it. So glad you shared your reivew.

One of the particularly fascinating aspects of Watson’s tale is that — although it was not that long ago, WWII and the explosive growth in US industry in the aftermath — yet he often describes a world that is almost unrecognizable today. The past really is a different country.