The news about public opinion and political debate in Britain is not good, I am afraid. My evidence is the recent brouhaha, possibly noticed by some American readers of this blog but probably not. It is, however, important in what it indicates. The fuss is about the Leader of the Opposition, Prime Minister in waiting (theoretically) and newly reborn firebrand socialist, Ed Miliband and his father, influential left-wing Marxist thinker and writer, Ralph Miliband. I put up a longish piece on Your Freedom and Ours and my unhappy conclusion is that, for the time being at least, the Ralph Milibands of this world have won the battle for the hearts and minds of the establishment, political and media.

Britain

301 Years of Steam Power

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen erected a steam engine of his own design near Dudley, in the West Midlands of England, thereby kicking off the age of steam. (Yes, this would have made a better post last year, to mark a round 300-year anniversary, but better late than never..)

We were told in the 5th grade that the steam engine had been invented by James Watt after noticing the way that the steam pressure in a teapot could cause the lid to lift a little. A nice story, but (a) James Watt did not invent the steam engine, and (b) early steam engines did not work the way that the teapot story would suggest.

In ancient Greece there were some experiments with the use of steam power to create mechanical motion; thereafter nothing significant happened in this field until the late 1600s, when Thomas Savery invented a device for raising water by steam: it was intended to address the growing problem of removing water from mines. Savery’s invention was conceptually elegant, with no moving parts other than the valves: unfortunately, it could not handle a water lift of more than about 30 feet, which was far insufficient for the very deep mines which were then becoming increasingly common.

Newcomen’s engine filled a cylinder with low-pressure steam, which was then abruptly cooled by the injection of a water jet. This created a partial vacuum, which pulled the piston down with great force–these were called “atmospheric” engines, because the direct motive force came from air pressure, with the role of the steam being simply to create the vacuum when condensed. After the piston reached the bottom of the cylinder, it would be pulled upwards by a counterweight, and the cycle would repeat. (See animation here.) Conceptually simple, but modern reconstructors have found it quite difficult to get all the details right and build an engine that will actually work.

These engines were extremely inefficient, real coal hogs, requiring about 25 pounds of coal per horsepower per hour. They were employed primarily for water removal at coal mines, where coal was by definition readily available and was relatively cheap. But as the cotton milling industry grew, and good water-power sites to power the machinery became increasingly scarce, Newcomen engines were also employed for that service. For example, in 1783 a cotton mill–complete with a 30-foot waterwheel–was constructed at Shudhill, near Manchester..which seemed odd given that there was no large stream or river there to drive it. The mill entrepreneurs built two storage ponds at different levels, with the waterwheel in between them, and installed a Newcomen engine to recycle the water continuously. The engine was very large–with a cylinder 64 inches in diameter and a stroke of more than 7 feet–and consumed five tons of coal per day.

Despite their tremendous coal consumption and their high first cost, a considerable number of these engines were installed, enough that someone in 1789 referred to the Newcomen and Savery engines in the Manchester area as common old smoaking engines. The alternative to the Newcomen engine described above would have been the use of actual horses–probably at least 100 of them, if my guesstimate of 40 horsepower for this engine is correct. These early engines resembled the mainframe computers of the early 1950s, in that they were bulky, expensive, resource-intensive, and limited in their fields of practical applicability…but, within those fields, absolutely invaluable.

A very small constitutional earthquake

By now, there can be nobody in the United States who is even remotely interested in foreign affairs who does not know that on Thursday the government in Britain suffered a defeat in the House of Commons with a clearly hostile debate in the House of Lords over the question of whether to intervene militarily in Syria.

Much has been made that this is the first defeat for a government over matters of war since some imbroglio in the eighteenth century when the Prime Minister was Lord North. The reason is actually simple: the government does not have to go to Parliament over either declaration of war and actual acts of war. These come under the Royal Prerogative, which is now vested in the government of the day and all attempts to change that through legislation have failed. However, Tony Blair found it necessary to ask Parliament (several times) about the war in Iraq and got his authorization. It would have been impossible for David Cameron to do otherwise but his case was quite genuinely not good enough to pass muster.

I wrote a blog a few days ago, in which I put together some of the questions that, in my opinion, those clamouring for intervention needed to answer. This has not happened to any acceptable degree and even after the vote, those who are hysterically lambasting the MPs refuse to do so, constantly shifting the ground as to why we should intervene.

Since the vote, which was immediately accepted by the Prime Minister, possibly with secret relief, I became involved in ferocious disputations on the subject. In the end I decided to sum up the situation as I saw it in another, rather long, blog. It is largely about the situation as far as Britain is concerned so it may be of interest to readers of this blog.

For the record, I do not think this is the end of the Special Relationship, which exists on many more levels than political posturing. As I say in the blog, if it survived Harold Wilson’s premiership, it will survive the Obama presidency. Some things are more important than immediate and confused politicking.

Max von Oppenheim, German counterpart to Lawrence of Arabia

Max von Oppenheim was a German ancient historian, and archaeologist who also worked as a diplomat and spy for the German Empire during the First World War. In those latter two capacities, he basically tried to incite Jihad against the Entente powers. From Wikipedia:

During World War I, Oppenheim led the Intelligence Bureau for the East and was closely associated with German plans to initiate and support a rebellion in India and in Egypt. In 1915 Henry McMahon reported that Oppenheim had been encouraging the massacre of Armenians in Mosques.[12]

Oppenheim had been called to the Wilhelmstrasse from his Kurfurstendamm flat on 2 August 1914 and given the rank of Minister of Residence. He began establishing Berlin as a centre for pan-Islamic propaganda publishing anti-Entente texts. On August 18 1914 he wrote to Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to tell him that Germany must arm the Muslim brotherhoods of Libya, Sudan and Yemen and fund Arab exile pretenders like the deposed Egyptian Khedive, Abbas Hilmi. He believed Germany must incite anti-colonial rebellion in French North Africa and Russian Central Asia and incite Habibullah Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, to invade British India at the head of an Islamic army.[13] Oppenheim’s Exposé Concerning the Revolutionizing of the Islamic territories of our enemies contained holy war propaganda and ‘sketched out a blueprint for a global jihad engulfing hundreds of millions of people’. Armenians and Maronite Christians were dismissed as Entente sympathizers, quite useless to Germany nicht viel nutzen konnen. [14]

Because Germany was not an Islamic power the war on the Entente powers needed to be ‘endorsed with the seal of the Sultan-Caliph’ and on 14 November 1914 in a ceremony at Fatih Mosque the first ever global jihad had been inaugurated. The impetus for this move came from the German government, which subsidized distribution of the Ottoman holy war fetvas, and most of the accompanying commentaries from Muslim jurists, and Oppenheim’s jihad bureau played a significant role. By the end of November 1914 the jihad fetvas had been translated into French, Arabic, Persian and Urdu.[15] Thousands of pamphlets emerged under Oppenheim’s direction in Berlin at this period and his Exposé declared that, “the blood of infidels in the Islamic lands may be shed with impunity”, the “killing of the infidels who rule over the Islamic lands” , meaning British, French, Russian, and possibly Dutch and Italian nationals, had become ” a sacred duty”. And Oppenheim’s instructions, distinct from traditional ‘jihad by campaign’ led by the Caliph, urged the use of ‘individual Jihad’, assassinations of Entente officials with ‘cutting, killing instruments’ and ‘Jihad by bands’,- secret formations in Egypt, India and Central Asia.[16]

“During the First World War, he worked in the Foreign Ministry in Berlin, where he founded the so-called “message Centre for the Middle East”, as well as at the German Embassy in Istanbul. He sought to mobilize the Islamic population of the Middle East against England during the war and can be seen thus almost as a German counterpart to Lawrence of Arabia. The AA pursued a strategy of Islamic revolts in the colonial hinterland of the German enemy. The spiritual father of this double approach, the war first, by troops on the front line and secondly by people’s rebellion “in depth” was by Oppenheim.”[citation needed]

The German adventurer met with very little success in World War I. To this day, the British see him as a “master spy” because he founded the magazine El Jihad in 1914 in an effort to incite the Arabs to wage a holy war against the British and French occupiers in the Middle East. But his adversary Lawrence of Arabia, whom he knew personally, was far more successful at fomenting revolts.[17]

Lawrence of Arabia, aka T. E. Lawrence was successful because he didn’t appeal to religious fervor, but rather to the far more basic sentiment of ethnic solidarity against an oppressor of different ethnic origin. In other words, the Arabs cared far more about their struggle against the Turkish Empire than they did about religion, leave alone jihad.

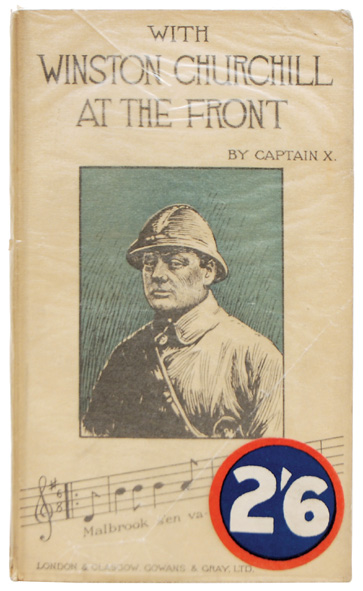

History Friday: With Winston Churchill at the Front

I am reading Churchill: A Study in Failure (1970), by Robert Rhodes James. It is a famous book, which describes Churchill’s career up to 1939. It is an excellent book as of page 132/385. In fact, it is so good, I now want to read other things by this author.

A relatively little-known episode in Churchill’s career was his uniformed service at the front in World War I. Following the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, which was Churchill’s brainchild, he was driven out of the cabinet, where he had been First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill volunteered for active service, and was given the command of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers battalion from January to May, 1916.