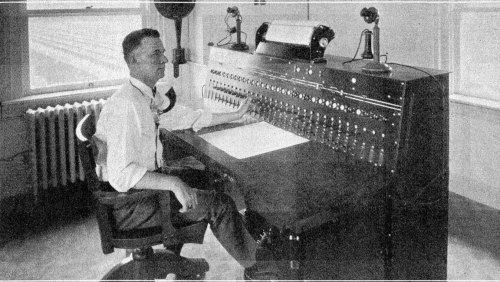

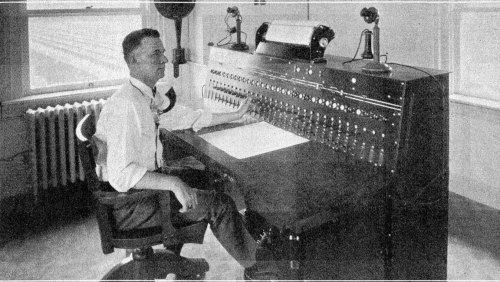

Ninety years ago this month, the first Centralized Traffic Control system was placed in operation, on a 40-mile stretch of railroad belonging to the New York Central. From a central console, the Dispatcher was able to control switches and signals anywhere in the territory. The positions of individual trains were displayed via lights on the panel. Interlocking logic at the remote locations ensure that neither dispatcher errors nor communication problems could set up potentially-dangerous conflicts.

In today’s terminology, it was a geographically-distributed robotics system, with a strong flavor of what is now being called the Internet of Things–although the communications links in the system were not provided by the Internet, obviously, the concept of devices announcing their status via telecommunications and receiving commands the same way was quite similar.

To railroad men of the time, the new system seemed almost magical:

The dispatcher was there and he was just filled up with enthusiasm on this new gadget called centralized traffic control… Along about 10 o’clock, he just yelled right out loud, ‘Here comes a non-stop meet.’ We all gathered around the machine and watched the lights that you know all about, watched the lights come towards each other and pass each other without stopping. That, to me… was history on American railroads, the first non-stop meet on single track without train orders… and you never saw such enthusiasm in your life as was in the minds and hearts of that crew.

CTC technology caught on quickly, and by the mid-1930s, stretches of track up to 100 miles long were regularly being operated under CTC control. In principal, there was no limit to how far away the operator could be from the controlled railroad territory.

I post items like this because they provide needed perspective in our present “age of automation” when there is so much media focus of robotics, artificial intelligence, and ‘the Internet of Things,’ but not a whole lot of understanding for how these fit on the historical technology growth trajectory.