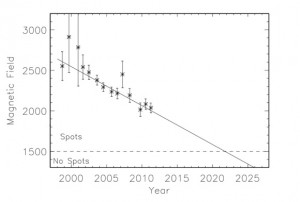

It looks as though the sun is entering a new dormant period, similar to the Maunder Minimum which led to the Little Ice Age.

This will almost certainly end the global warming hysteria in a few years. The people who continue to cling to this sort of hoax, will be looking for the Next Big Thing. I don’t mean to imply that the earth did not warm over the past century. The Little Ice Age ended about 1850 so a warming trend is expected following such an event. The hoax is the contrived evidence that humans are responsible. I was skeptical about that from the first. The forces involved are too large. If humans affected climate, it probably began with the development of agriculture. Perhaps we have had no ice age in the past 10,000 years because of the effects of agriculture and forest changes. I have previously discussed this and nothing has changed my mind.

The next question is what will replace global warming as the religion of the bored classes ? There are signs that it may be “New Age” medicine. This sort of thing is common in certain circles and has considerable similarity to the global warming arguments.

The Center for Integrative Medicine, Berman’s clinic, is focused on alternative medicine, sometimes known as “complementary” or “holistic” medicine. There’s no official list of what alternative medicine actually comprises, but treatments falling under the umbrella typically include acupuncture, homeopathy (the administration of a glass of water supposedly containing the undetectable remnants of various semi-toxic substances), chiropractic, herbal medicine, Reiki (“laying on of hands,” or “energy therapy”), meditation (now often called “mindfulness”), massage, aromatherapy, hypnosis, Ayurveda (a traditional medical practice originating in India), and several other treatments not normally prescribed by mainstream doctors. The term integrative medicine refers to the conjunction of these practices with mainstream medical care.

Here we have what may become the replacement for AGW in the minds of the exquisite privileged class. It has all the requirements.

1. America is corrupt and inferior ? Yes. (See the comments)

2. Capitalism is corrupt and inferior ? Yes

3. Only the truly intelligent and sensitive can appreciate it ? Well.

You might think the weight of the clinical evidence would close the case on alternative medicine, at least in the eyes of mainstream physicians and scientists who aren’t in a position to make a buck on it. Yet many extremely well-credentialed scientists and physicians with no skin in the game take issue with the black-and-white view espoused by Salzberg and other critics. And on balance, the medical community seems to be growing more open to alternative medicine’s possibilities, not less.

That’s in large part because mainstream medicine itself is failing. “Modern medicine was formed around successes in fighting infectious disease,” says Elizabeth Blackburn, a biologist at the University of California at San Francisco and a Nobel laureate. “Infectious agents were the big sources of disease and mortality, up until the last century. We could find out what the agent was in a sick patient and attack the agent medically.” To a large degree, the medical infrastructure we have today was designed with infectious agents in mind. Physician training and practices, hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry, and health insurance all were built around the model of running tests on sick patients to determine which drug or surgical procedure would best deal with some discrete offending agent. The system works very well for that original purpose, against even the most challenging of these agents—as the taming of the AIDS virus attests.

But medicine’s triumph over infectious disease brought to the fore the so-called chronic, complex diseases—heart disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and other illnesses without a clear causal agent. Now that we live longer, these typically late-developing diseases have become by far our biggest killers. Heart disease, prostate cancer, breast cancer, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic diseases now account for three-quarters of our health-care spending. “We face an entirely different set of big medical challenges today,” says Blackburn. “But we haven’t rethought the way we fight illness.” That is, the medical establishment still waits for us to develop some sign of one of these illnesses, then seeks to treat us with drugs and surgery.

No doubt the author would prefer that people died too young for chronic disease to affect them.

A well-known science blog states the case for scientific medicine.

Speaking of bad ideas, in contrast to his previous article, in which he managed at least to get the gist of what Ioannidis teaches but merely spun it in what I considered to be an annoying fashion, the entire idea behind Freedman’s new article channels the worst fallacies of apologists for alternative medicine. The whole idea behind the article appears to be that, even if most of alternative medicine is quackery (which it is, by the way), it’s making patients better because its practitioners take the time to talk to patients and doctors do not. In other words, it’s a massive “What’s the harm?” argument. Yes, that’s basically the entire idea of the article boiled down into a couple of sentences. Deepak Chopra couldn’t have said it better. Tacked on to that bad idea is a massive argumentum ad populum that portrays alternative medicine (or, as purveyors of quackademic medicine like to call it, “complementary and alternative medicine” or “integrative medicine”) as the wave of the future, a wave that’s washing over medicine and teaching us cold, reductionistic doctors to care again about patients and thus make them better. Freedman even contrasts this to what he calls the “failure” of scientific medicine. I kid you not. Worse, Freedman makes this argument after having actually interviewed some prominent skeptics, including Steve Salzberg and Steve Novella, in essence, missing the point.

I expect to see more and more of “alternative medicine” because it appeals to the scientific illiterate and it damns another traditional source of authority, scientific medicine. Global warming hysteria attacks capitalism and prosperity. Alternative medicine is also going to be useful to Obamacare as a way of cutting reimbursement for traditional care. There are assumptions that it is cheaper. It may be cheaper per session, although is also uncertain, but there is no end point to such treatment. Who can say when the treatment is enough if it cannot be measured ? The theory that it is cheaper will be a powerful wind behind it. Watch for more and more about it in the left leaning media.