[This post was originally published in 2013. Re-posting to allow a new comment. Jonathan]

Logistics, the ability to transport and supply military forces, underwrites military strategy. The importance of logistics is the reason for the adage, “Amateurs talk tactics while professionals talk logistics.” These truisms of military affairs are often glossed over by General Douglas MacArthur’s critics — like US Naval Historian Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison — and replaced with talk of MacArthur “Seeking Personal Glory” and taking “Unnecessary Casualties.” This was especially true when it came to MacArthur’s liberation of the Southern Philippines. MacArthur’s Southern Philippines campaign, far from being “unnecessary” and a “strategic dead end,” was a logistical enabler for Operations Olympic and Coronet, the American invasion plans for the islands of Kyushu and Honshu Japan.

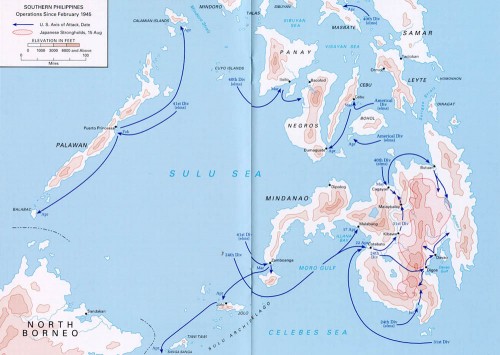

MacArthur had been directed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff to be able to stage through the Philippines 11 divisions by November 1945 and a further 22 by February 1946. The securing of the Southern Philippines would cut off Japanese small boat production there, protected MacArthur’s sea lines of communication filled with small boats and a polyglot freighter fleet from both radar and radio directed Japanese Kamikaze aircraft and suicide boats, and provide the vitally needed Filipino workforce for assembly work and port capacity to support the staging those divisions for the invasion of Japan.

To understand the Southern Philippine campaign in historical context, you need to know that MacArthur’s liberation of the Philippines was done in four phases.

1) Sixth Army’s Leyte Campaign

2) Sixth Army’s Mindoro/Luzon Campaign

3) The Eighth Army’s the Leyte-Samar operation (including clearance of the Visayan passages)

4) The Eighth Army’s extended Southern Philippines campaign south of the Visayan passages

The first two phases are not included in the “waste of soldiers” critiques of MacArthur, while the other two usually are. So I will lay out MacArthur’s logistical reasons to pursue those “unnecessary” military operations as the relate to the invasion of Japan.

First, and a generally unknown fact, the Southern Philippines was very important for Japanese Army logistics in the Pacific. Davao, Mindanao in the Philippines was a center of manufacture of Japanese Army powered barges and small wooden freighters, called “Sea Trucks” in WW2 documents. The following is from page 32 of the 1947 United States Strategic Bombing Survey report titled “The Fifth Air Force in the War Against Japan” —

Losses in larger and faster ships, and the necessity of maintaining such vessels on the main routes of supply to Empire, caused the Japanese to resort to smaller shipping for inter-theater troop movements and supply. The “Sea Truck,” a small wooden ship of stylized construction (100/300 tons), became a most important factor in his surface movement from early 1943. The power barge was also made and used in large numbers. These vessels were manufactured at Soerbaja, Davao, and other places beyond our range of attack. They were used on long sea hauls at times, movement being traced from Philippines to Halmaheras and New Guinea in such vessels. They were used almost entirely in redistribution from supply termini in the combat zones. Fishing vessels, luggers, and prahus were also extensively used in intertheater supply and were capable of moving effective tonnage by their numbers and the ability to hide in small inlets. This small shipping became an increasingly important target for Fifth AF and regular hunts were made for it until its movement ceased.

MacArthur’s 5th Air Force did not have enough planes or supplies to wipe out those facilities without both killing a lot of innocent Filipinos and denying his own own troops in Luzon, as well as those with the American fleet at Okinawa, badly needed air support. This was particularly important in terms of suppressing Japanese airfields on Formosa that were sending Kamikaze’s to Okinawa from April -thru- June 1945. Every long range bomber strike sent to Davao, had it been by-passed, would have been one diverted from Formosa during that time.

Second, in the Pacific War, logistical “opportunity costs” were measured in terms of Amphibious sea lift and merchant shipping tonnage. The reason for this was tied into the issues of shipping capacity, port capacity and the organization of amphibious assaults.

U.S. Navy historians including Samuel Elliot Morrison denigrate MacArthur’s moves in the Southern Philippines, the Visayan passages specifically, while glossing over the logistical realities of MacArthur’s coastal shipping. This line of argument lets the Navy off the hook for how badly they went out of their way sabotage MacArthur on shipping and naval support (This story and a number of others I intend to expand on in later columns).

MacArthur had three more or less distinct types of coastal shipping pools operating with the Southwest Pacific Area’s (SPWA) 7th Fleet:

1) Large vessels that were US Army or War Shipping Administration vessels assigned to Army including Dutch East Indies tramp steamers and Vichie French vessels (along with freighters commandeered by MacArthur as floating storage when they arrived with intentions of return). These were the Army Transport Service (ATS) vessels that were, under a 1941 reorganization, integrated into the Water Division of the US Army Transportation Corps. They were manned by American & Australian merchant seamen in part, but primarily by the US Coast Guard on newer ship after mid-1944.

.

2) The small ships and boats section with watercraft of less than 1,000 tons displacement, almost exclusively of local SWPA origin with some built for the U.S. Army in Australia’s small boatyards, that were essential for operating in the coral filled waters of Northern Australia, the Coral Sea and Papua/New Guinea. They were crewed by a mix of citizens of Australia, New Zealand and some Papuans..

3) The US Army Engineer Special Brigades (ESB) in LCVP and LCM landing craft. Each US Army Engineer Special Brigade — and MacArthur had three in the Philippines, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Brigades — was equipped to transport and land a division in a “Shore to shore” operation of under 135 miles. (which was the practical maximum overnight range of a LCM combat loaded with a M4 Sherman tank.) These brigades required a force of 7340 men, 540 LCMs and LCVPs, and 104 command and support boats too move that division. You can find an excellent site dedicated to the ESB’s here — http://ebsr.net/ESBhistory.htm

When MacArthur moved into the Philippines, these coastal fleets moved from Hollindia, Walde, Morotia, etc to Leyte to maintain the distribution of supplies to his ground forces from ports where the larger ships brought supplies. They were still extremely vulnerable to interdiction from anything. Especially the suicide motor boats and small numbers of aircraft the Japanese cached at bases all over the Southern Philippines to interdict MacArthur’s sea lines of communications.

Mindanao was infested with both Japanese radars and suicide small boats (Called Q-Boats in the staff messages of SWPA theater) which threatened MacArthur’s small freighter convoys and small boat distribution sea lines of communications. The following text I clipped below can be fund on page 651 of ENGINEERS OF THE SOUTHWEST PACIFIC 1941-1945, Volume IV, Amphibian Engineer Operations.

Boat Missions

.

Boat operations by 533d EBSR craft in Davao Gulf included a shore-to-shore landing on 15 May on Samal Island, which lies offshore from Davao. (See Maps Nos. 31 and 33.) Japanese artillery on Samal had proved harassing and occasionally destructive; an enemy shell on one occasion struck a portable surgical hospital and killed 7 men and wounded 9. To destroy the Japanese gun emplacements the 3d Battalion, 19th Infantry, was transported to Samal in LCM’s and LVT’s of Company B, 533d , the expedition being supported by 2 LCM gunboats. The Japanese were hunted down in the island’s rocky interior or were forced to flee to the mainland. Later in May the LCM’s of Company ? were employed to support the advance of the 24th Division along the coast northeast of Davao. The boats were frequently under fire by small arms and light artillery..

LCM gunboats and rocket craft were also employed in daylight attacks upon Japanese Q-boat hideouts on the east coast of Davao Gulf.395 A 5-day raiding mission to destroy Japanese radar installations in southern Mindanao marked 533d EBSR boat operations in late May and early June.

Third, MacArthur’s issues with port capacity and workforce shortages brings us to the way freighters were packed in WW2. Logistically, there were four ways to load a freighter.

1. Amphibious Landing Combat loaded with equipment/supplies stacked in the hold for rapid debarkation in order of use in an amphibious assault.

.

2. Theater Unit loaded with organization equipment and units placed on the same ship or in multiple ships in the same convoy.

.

3. Commercial loading with minimal weapon dis-assembly, consistent with freighter space availability & center of gravity, with unit loads of equipment spread over several convoys weeks or months apart.

.

4. Maximum freighter space utility with vehicles and equipment requiring a factory or depot assembly at the other end to reassemble the major weapons systems involved.

Every amphibious landing had to take freighters loaded out as in #2 through #4 above, unload them. Then combat load the contents into Amphibious assault shipping, plus some number of the freighters that were unloaded. Then stage the shipping out in convoys in order of use at landing. In terms of shipping space, Amphibious combat loading was less than 1/2 the efficiency of commercial loading and 1/4 the shipping efficiency of “factory reassembly loading” above. (See Dunnigan and Nofi’s “VICTORY AT SEA: World War II in the Pacific” in the notes)

The typical amphibious assault in WW2 was in three echelons:

1. The Assault echelon with 70% or less of the vehicles and 100% of the infantry.

.

2. The follow-on echelon that filled out artillery and other combat support. Then finally,.

3. The third echelon that completed the rest of the Assault Division and higher level assets for things like heavy Ordnance repair, usually in 1st echelon assault landing shipping making a 2nd round trip.

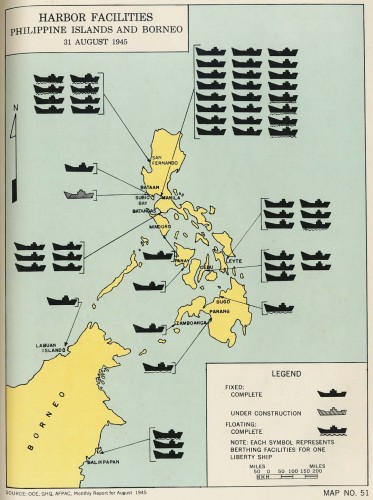

Even when some of the Southern Philippines ports were made “logistically barren” by the Japanese in terms of supplies after capture. They were still highly useful in future operations to have available against Japan to in order to unload and repack shipping for an invasion. If only for the real estate available to unload and water resources. Since the Southern Cebu City, Cebu and Iloilo on Panay were the second and third largest cities respectively in the Philippines at the time. They had lots of valuable port real estate and water. (See engineer map below)

One of the often overlooked geographic/logistical issues of Central and South Pacific islands were that they were especially low on fresh drinkable water. You needed water for those 2nd and 3rd echelon servicemen waiting for their reinforcement convoys as well as the servicemen doing the port clearance work.

Which brings up the final thing Southern Philippine ports had addition to port capacity and water. They had Filipino port workers as “force multipliers” for a chronically short of bodies SWPA Army Service force.

Only MacArthur’s SWPA and the Persian Gulf Command’s Lend lease shipping routes used “factory reassembly loading” to any great extent. MacArthur used factory loading for his LCVP and LCM landing craft, and for General Motors (GM) 2.5 ton trucks for use in Australia and New Guinea. The only other American shipping route in WW2 that used this supply method was with Lend Lease trucks through the British controlled Middle East theater to the Persian Gulf theater for use by the Russians.

When MacArthur’s Northern Australian landing craft factory fell out support range in his Western New Guinea, Leyte and Luzon campaigns. The landing craft factory was shut down and reestablished in Manila. This meant that about 1/2 the LCVP and LCM boat hulls to be used in the ESB’s for Operation Olympic were 12-18 month old Western New Guinea campaign veterans for the Kyushu landings.

MacArthur’s “Little Detroit” GM truck assembly plant was first in Southern Australia, to support the road logistics to Darwin in North West Australia. This road link was mainly operated by African American truck drivers in 1942-1943 in a “Red Bull Dust Express” far longer and tougher than the “Red Ball Express” that happened in France in 1944. “Little Detroit” was then later relocated to Milne Bay in South Eastern New Guinea for the 1944 Western New Guinea campaign.

For the invasion of Japan, MacArthur initially wanted Manila to become a supply base similar to Paris for General Dwight D. Eisenhower in Europe. In particular, he wanted to do more of the the same “factory reassembly loading” with the rest of his supply chain to Manila for the invasion of Japan, but got shot down as much for as much for “unofficial” inter-service political reasons as “official” ones relating to time and shipping shortages given by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“Factory disassembled” equipment is not usable to intermediate combat forces without the assembly plant at the port of debarkation to put equipment back together. Had MacArthur’s supply chain gone to maximum shipping space efficiency to Manila, using relatively abundant Filipino labor to reassemble vehicles and supplies, the Navy could not “Theater Command Midnight Requisition” equipment en-route to the SWPA the way Halsey did to General MacArthur, to include a high priority shipment of National Defense Research Committee aircraft rockets in 1943. (This story and the thieving ways of Pacific War resupply will be the subject of a later column.)

Nimitz did not have in Hawaii, nor later on Guam, anything approaching the work force and facilities to prey upon MacArthur’s disassembled supplies. Admiral Halsey was never able to steal either MacArthur’s disassembled Engineer Special Brigade landing craft nor his “Red Bull Dust Express” trucks during Operation Cartwheel, the campaign that isolated the Japanese forward base at Rabaul, for just that reason.

When MacArthur set up shop in the Philippines, all his freighters skipped Pearl Harbor as an intermediate convoy stop. This put his supplies outside the reach of Adm. Nimitz…until Nimitz set up shop as a theater commander on Guam, where the convoys did stop for fuel, escorts and especially water.

When MacArthur’s Philippines Base Development plans (referred to as the “FILBAS Plan” in logistical planning documents and official Army histories) fell through in the spring-summer of 1945, both due to the Japanese destruction of port facilities in Manila and other Southern Philippines ports, and world wide shipping shortages. He requested that Operation Olympic’s fast freighter resupply echelons — the first ships to arrive after the amphibious assault in a modified “theater load” configuration carrying base development supplies — be staged directly from San Francisco and Seattle ports of embarkation to both Okinawa and Kyushu. This would avoid the forward port congestion issue and it would mark the first time in WW2 that the US Navy and USMC would not be sitting as a vulture on MacArthur’s lines of resupply for a major operation.

Now you can understand why Admiral Morison and other critics of MacArthur always used ad hominem character assaults and never logistics arguments when they criticized MacArthur’s Southern Philippines campaign.

Military Acronyms

APA — Auxiliary Assault Transport

AKA — Auxiliary Cargo Transport

EBSR — Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment

ESB — Engineer Special Brigade. There were thrre such brigades in the SWPA. Each ESB was made up of three EBSR, a maintenance battalion, and various smaller support units. Each ESB was capable of moving one US Army infantry Division in a “Shore to Shore” movement of less than 135 miles.

LCM — Landing Craft, Mechanized. The LCM-3 was a 50-foot steel hulled landing craft and the LCM-6 was 56 feet long

LCVP — Landing Craft Vehicle and Personnel. A 36-foot wooden landing craft that has 1/4 to 1/5 the cargo capacity of an LCM, but could be stacked three to a US Navy APA or AKA davit.

LVT — Landing Vehicle, tracked. This was a series of 14-ton tracked amphibian vehicles in troop carrying tractors and turreted tank variants. The SWPA used the LVT-1, LVT-2, LVT(A)-2 and LVT-4 Tractors as well as both the LVT(A)-1 and LVT(A)-4 Amphibian Tanks.

Q-Boat — Originally “Q-boat” was the name of a British motor torpedo boat design that the pre-war Filipino Colonial government bought at MacArthur’s urging. Later the term “Q-boat” referred to all Imperial Japanese Navy “Shinyo” and Imperial Japanese Army “Renrakutei” suicide boats.

Notes and Sources:

Links consulted —

2d Engineer Special Brigade , http://www.2esb.org/04_History/Book/Chapter_01.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

3rd Engineer Special Brigade, http://ebsr.net/, Last accessed 6-06-2013

An Even More Forgotten Aspect of the “Forgotten Fleet”, http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/rj/swpa/forgotten.htm#schubert, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Amphibian Engineers, http://ebsr.net/ESBhistory.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Army Ships — The Ghost Fleet, http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/Army.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Army FP/FS Vessels, http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/rj/fs/fs.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Composition of the Army Fleet in the Southwest Pacific, excerpt from Pages 317-338 of “U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941-1947” by Dr. James R. Masterson, Transportation Unit, Historical Division, Special Staff, U. S. Army October 1949 http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/Masterson.html Last accessed 6-06-2013

R. Jackson, Army Ships — The Ghost Fleet South West Pacific Area (SWPA), “Forgotten Fleet” by Bill Lunney and Frank Finch, a Review and commant by R. Jackson, http://patriot.net/~eastlnd2/rj/swpa/forgotten.htm, Last accessed 6-06-2013

John W. Mountcastle (Introduction) “Southern Philippines: The US Army Campaigns of World War II” CMH Pub 72-40 http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/southphil/southphils.htm

Captain E. A. Flint, MBE, ED (Retd), “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” printed in the Journal , “ United Service “ Volume 55 No. 4 Pages 15-20, March 2005 issue, http://www.usarmysmallships.asn.au/html/form_doc.html, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Trent Telenko “History Friday: MacArthur — A General Made for Convenient Lies.” May 31, 2013

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/36378.html

Trent Telenko “History Friday: MacArthur’s ‘Red Bull Dust Express'” June 14, 2013,

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/36669.html

U.S. Army Small Ships Association Incorporated, http://www.usarmysmallships.asn.au/html/fleet.html, Last accessed 6-06-2013

The full version of “U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941-1947” can be found in eight parts at the following link — http://cgsc.cdmhost.com/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/p4013coll11&CISOPTR=903&REC=1

THE UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY, The Fifth Air Force in THE War Against Japan, Military Analysis Division, June 1947, Call number: 39999063173312, http://www.archive.org/details/fifthairforceinw00unit, Last accessed 6-06-2013

World War II Coast Guard-Manned U.S. Army Freight and Supply Ship Histories, http://www.uscg.mil/history/webcutters/FS_Vessels.asp, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Books Consulted —

Robert Amory (author) and Reuben Miller Waterman (editor), Surf and Sand: The Saga of the 533d Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment and 1461st Engineer Maintenance Company 1942-1945, Andover, Mass., Printed by the Andover press, ltd., 1947

Joseph Bykofsky and Harold Larsoll, Chapter X, passim, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, The Technical Services, THE TRANSPORTATION CORPS: OPERATIONS OVERSEAS CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1990 (1st Printing 1957 as CMH Pub 10-21)

MAJOR GENERAL HUGH J. CASEY, “ENGINEERS OF THE SOUTHWEST PACIFIC 1941-1945, Volume IV, Amphibian Engineer Operations;” By the Office of the Chief Engineer, General Headquarters Army Forces, Pacific, Chief Engineer; REPORTS OF OPERATIONS UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES IN THE FAR EAST, SOUTHWEST PACIFIC AREA, ARMY FORCES, PACIFIC 1959, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?q1=Q-Boat;id=mdp.39015027335275;view=image;start=1;size=100;page=root;seq=7;num=iii, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Ray S. Cline, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, The War Department, WASHINGTON COMMAND POST:THE OPERATIONS DIVISION, First PrinLted 1951-CMH Pub 1-2 www.history.army.mil/html/books/001/1-2/CMH_Pub_1-2.pdf

Robert W. Coakley and Richard M. Leighton, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, The War Department, GLOBAL LOGISTICS AND STRATEGY 1943-1945, www.history.army.mil/html/books/001/1-6/CMH_Pub_1-6.pdf

Page 588

“Of the 36 Army and Marine divisions to be engaged in OLYMPIC and CORONET, 30 were to stage and mount in the Philippines, 3 in the Ryukyus, 2 in Hawaii, and 1 on Saipan. Also, 3 or 4 divisions would be employed as a garrison in the Philippines, 2 or 3 in the Ryukyus. The planners calculated that there would have to be facilities in the Philippines to handle a peak load of 22 divisions by November 1945 and for simultaneously mounting 11 divisions for CORONET in February 1946.”

Page 598

MacArthur meanwhile had decided that once the invasion of Kyushu was under way, supply shipments could be made directly to that area rather than to intermediate depots in the Philippines.

James F. Dunnigan and Albert Nofi, “VICTORY AT SEA: World War II in the Pacific,” William Morrow and Company Inc. , Mew York, c 1995, pages 322 – 327

David H. Grover, U.S. Army Ships and Watercraft of World War II Annapolis, Md. by the Naval Institute Press, 1987 ISBN: 0870217666

William F. Heavey, Down Ramp! the Story of the Army Amphibian Engineers, Coachwhip Publications, 2010, ISBN 1616460571, 9781616460570, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89058523069;q1=Down%20Ramp%21%20the%20Story%20of%20the%20Army%20Amphibian%20Engineers, Last accessed 6-06-2013

Bill Lunney Forgotten Fleet: a history of the part played by Australian men and ships in the U.S. Army Small Ships Section in New Guinea, 1942-1945; Forfleet Publishing, 7 Wade Close, Medowie NSW 2318, Tel. 049 828437; ISBN 0 646 26048 0

What on earth was the point of this campaign? Surely the Allies should have been aiming to knock Japan out of the war rather than liberating every bit of Japanese-held territory? The obvious exception would be any territory providing Japan with supplies essential to her war effort.

What on earth was the point of this campaign? Surely the Allies should have been aiming to knock Japan out of the war rather than liberating every bit of Japanese-held territory? The obvious exception would be any territory providing Japan with supplies essential to her war effort. Did “powered barges and small wooden freighters” really fit the bill? Sounds unlikely.

Trent, this is really superb and informative.

Given limited public awareness of real logistics, consider spiffing up the book chapter with some real shipping tonnage numbers for division slices in transport, for buildup of long-term supply/fuel/munitions stocks per division slice, and monthly support requirements (maintenance and combat separately) per division slice in the immediate operations areas. Describe the implications of the Pacific being an unimproved theater of operations, and the importance of friendly forward labor in Australia and the Philippines.

Hmm, Trent, I suspect your post closes with italics open so that all reader comments are italicized too. Please fix those.

Fixed.

>>What on earth was the point of this campaign?

Winning the war.

The Japanese were an irrational foe. Any sane government would have negotiated surrender after the loss of both the Japanese Naval Air Arm and the islands themselves after “The Marianas Turkey Shoot,” IOW, before the invasion of Leyte in Oct 1944.

Since at the time it looked like it would take large numbers of American soldiers sticking bayonets in the guts of the last Japanese soldiers in the Mountains of Honshu to win the war. Taking intermediate ports to support the invasion of Japan was going to happen.

Note as well that Mac Arthur was not brought into the A-bomb secret until Late June/Early July 1945.

All his actions prior to that were keyed to the invasion of Japan and the fact that the Japanese murdered 100,000 Filipinos in the fighting at Manila. MacArthur was not going to leave any Filipinos in Japanese hands given what happened at Manila and Ultra code breaking that said the Japanese would murder all allied POW and as many allied civilians as they could catch in the event of the invasion of Malaya and the Japanese home islands.

>> Surely the Allies should have been aiming to knock Japan out of the

>> war rather than liberating every bit of Japanese-held territory?

The majority of the Southern Philippines — the countryside — was already held by American supported guerrilla’s.

The militarily useful bits — the cities, airfields, ports and land adjacent to strategic waterways — were garrisoned by the Japanese. Those were the where Mac Arthur’s forces went to eject them.

Once the Japanese were driven into the hills, the guerrilla’s, with minor American air support, hunted them down.

“Unnecessary Casualties”?

Tarawa? Makin?

And yes, the southern campaigns were important.

They had to get the bomber infrastructure close enough to Japan do large scale damage. That mean taking, and shielding, the Marianas, at the very least. You weren’t going to secure the Marianas while the IJN was still in the Phillipines.

Unfortunately, it also meant Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Tarawa was a serious failure of planning, in which the tides were not understood. Pelilieu was the worst example of unnecessary casualties and that was, as I understand it, a Navy objective. Until doing some recent reading I had no idea of how many POWs were being held in Japan and subject to the order of massacre if an invasion occurred. It was more than 10,000.

The US Navy opposing Philippines campaign in favor of Formosa might be a myth. Per:

https://history.army.mil/books/70-7_21.htm

“With the possible exception of Nimitz, the ranking … Navy commanders in the Pacific … were opposed to the seizure of Formosa. … the consensus of most high-ranking Army and Navy planners in Washington – with Leahy and General Somervell as outstanding exceptions – was that the Formosa-first course of action was [best]”

Note that link is a chapter from the book “”Command Decisions” by the U.S. Army’s Center for Military History, a 1960 book. So perhaps outdated?

Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell was the chief logistician of U.S. Army. The link above also has:

“Somervell, … favored taking the entire Philippine Archipelago”

I assume his reasoning was what Trent Telenko detailed?

“The Washington War” by James Lacey has a harsh assessment of Somervell. From my notes:

<>

Is this fair? Perhaps Somervell was just weak in production & made up for it by being very good

supplying overseas?

Was invasion of Borneo on 1 July 1945 a good idea?

Whoops — looks like this makes comments between ” disapear. What my notes on “The Washington War” by James Lacey has is:

Somervell’s obstinacy almost single-handedly wrecked nascent mobilization.

8/12/42 – Civilian economists said milt. requests at least

30% too high. With damage from huge undeliverable orders, Army might get less then 1/2 of what ordered.

JCS 10/20/42 – agreed $10B cuts for 1943. Not as much as economists wanted, but said doable.

Economists likely shortened war many months. W/o reduction Army goals, mass of material Allies hurled into D-Day would not been available until well into next year

Wars are won by the side with some combination of fewer really stupid mistakes, (never zero) and the most luck exploiting the mistakes of the other side. The side that can turn out a heavy bomber an hour and an escort carrier in three weeks probably has an advantage that makes up for a lot of stupid decisions too.

Look at a map of Formosa, A narrow strip along the western edge with the rest forested mountains to this day. It would have been an Iwo Jima that never ended. The invasion of Japan would have been our own Battle of the Somme times ten.

What a(nother) great Friday history post by Trent, I assume this one was part of his exploding narratives series.. To follow-up on what Tom commented on all those years ago, I would like to have seen in an expanded edition (whether in chapter or book form) go into further detail regarding tonnage requirements per division, port throughput on unloading/reloading transports, and just good ole military logistics issues in using the Philippines as a transshipment point for Olympic,

I would also like to see more information on the official logic behind the southern Philippine campaign; I looked through posts after this and I didn’t see any so perhaps I missed them, if so I apologize. I am a bit intrigued by the comment regarding the “falling-through” of MacArthur’s FILBAS Plan. If the collapse of FILBAS did not result in the strategic postponement of DOWNFALL then I have to ask how strategically necessary if not FILBAS was then at least the necessity of operations in the southern Philippines to secure more logistical capacity.

To paraphrase the line from LOTR (“One does not simply walk into Mordor”), one does not pull a full field army off the main line of advance into secondary operations that do not have a compelling strategic reason. Securing sea lines of communications against harassing operations is not one of them, there are better ways of doing that especially with friendly irregular forces in the area Clearly DOWNFALL did not need FILBAS. So what was it?

I think logic points further investigation into MacArthur’s compulsion to liberate the entirety of the Philippines as opposed to merely occupying the strategic parts. The strategic value of the Philippines lies in its position specifically in relation to Japan itself, not necessarily in what the islands themselves contain. That location made the invasion of the Philippines itself compelling, but I am not convinced further operations in the south.

I don’t mean to be nit picky here because this is a beautiful post, indeed the best posts and articles are not so much conclusive in of themselves but instead lay the groundwork for further inquiry. As I absorb the insights that Trent makes, the questions I generate are those more of things I myself have now become curious about rather than as criticisms. I think the proper tools for that next step would be analysis of the actual decision-makers involved and the choices that they were faced with.

I do not mean to dismiss MacArthur’s desire to liberate the Philippines out of hand. I have strong familial bonds with the Philippines through both blood and tradition and find the notion, even 80 years later, of leaving them under the Japanese yoke for 1 minute longer than necessary difficult to accept. However MacArthur had a possessive compulsion to liberate the entirety of Philippines that lay beyond any military necessity. Given the ties between the US and the Philippines as well MacArthur’s personal role that compulsion is understandable, indeed given the moral component admirable.

However I wonder if MacArthur’s use of the 8th Army in the southern Philippines is inseparable with his desire to liberate all of the country and if that desire to liberate all of the country from MacArthur’s darker nature. During the critical war conference in Hawaii in July 1944 among FDR, MacArthur, and Nimitz that was to decide the direction of advance beyond the Palau-Moroti line, MacArthur supposedly told FDR during a personal meeting that he was willingly to make a personal appeal to the nation if he (FDR) did not agree to the Philippine axis of advance. That is one of the most despicable acts of military insubordination in our history only to be rival led by…. MacArthur’s conflict with Truman concerning escalation during the Korean War. I see a pattern developing.

In fact to further develop the pattern both acts of insubordination concerned areas where MacArthur had his most devastating defeats. A connection? Perhaps I’m just biased because I find MacArthur a pompous a** who should have been cashiered in December 1950, if not after the Hawaii conference in 1944 and the notion that he would launch military operations to satiate his own military ego entirely too plausible. The good news about the southern Philippine operation was that it neither costly in terms of men and material nor in upsetting the overall timetable for OLYMPIC.

A wonderful post and I would love to know more about the topic. Any ideas for further investigation outside of the sources Trent cited?

Is Trent Telenko still around? Twitter has just implemented a change preventing anyone from seeing any twitter content without logging into a twitter account. I do not have such an account and categorically refuse to get one, but Mr. Telenko’s commentary on the current Ukraine situation has been very informative, as well as his linking to other sources. I’d very much appreciate it if he was to find an additional place to publish his commentary, and I doubt I’m the only one.

“I think logic points further investigation into MacArthur’s compulsion to liberate the entirety of the Philippines as opposed to merely occupying the strategic parts.”

This simultaneously gives MacArthur too much blame and too much credit. “I shall return.” should have been more properly; “We will return.” There was a lot more than MacArthur’s out sized ego in play.

First: The Philippines were American territory, full stop. Even more because MacArthur’s explicit reason for being Chief of the Philippines armed forces at the beginning of the war was to enable their immanent independence.

Second: The thousands of American and other POW’s who’s condition and treatment was well known throughout the service even if it was not to the public at large.

Third: Pretty much anyone in the service (all branches) for any time at the beginning of the war had spent time stationed there.

Fourth: Any invasion of the Japanese Home Islands was going to need more than a few small, scattered islands and much closer than Hawaii or Australia for transshipping troops and supplies. And if the last sixty-odd years has proven anything, it’s that trying to control a country from a few “strategic” points is a losing proposition.

Kaempi,

Try this:

https://threadreaderapp.com/user/TrentTelenko

It still works though, when he links to other twitters, you’re in the same fix. This points to a lot of other issues that may be coming to a head just now, but off topic.

We’re still waiting patiently for his book or books. Since he’s chosen, in part, to explore the mistakes, miscalculations and outright lies promulgated by different factions, he’ll certainly have material to fill an encyclopedia.

MCS,

I didn’t realize until Jonathan reposted this that Trent was working on a book. Alot of books get churned out every year on WW II (as with Civil War, and countless other topics) that fail to say anything new, a pitfall Trent has avoided . I hope Trent’s entire book is as provocative as that post was, it certainly got my mind a churning in a lot of ways, including historical methodology. Good times.