Previous Pacific War columns on Chicago Boyz have explored all sorts of World War 2 (WW2) narratives. This column, like the earlier “History Friday: MacArthur, JANAC, and the Politics of Military Historical Narrative” column is about exploring a historical narrative that should be there, but is not. One of the issues I have never seen addressed to my satisfaction by either the academic “Diplomatic History” or “Military History” communities were the command style & service coordination issues for the proposed invasion of Kyushu, AKA Operation Olympic. They were going to be huge.

The US Navy’s Central Pacific drive and MacArthur’s South West Pacific Area drive had much different command and communications styles that had to mesh for Operation Olympic (Which was about to be renamed ‘Operation Majestic’ for security reasons as the war ended). While both commands had multiple staff groups working on current operations, future operations and the evaluation of combat reports of past operations for lessons learned _simultaneously_. Adm Nimitz and Gen MacArthur had fundamentally different approaches to running those staffs and this caused conflicts. MacArthur effectively won this “staffing style war” — at a cost to the Olympic planning that will show up in a future column — by staying in Manila rather than moving his headquarters to Guam and forcing the US Navy to come to him to do the planning for Olympic. That however was not the end of the fun and games. It was only the beginning.

Operation Olympic would not only force those two Pacific Theater commands to work together, it would effectively see a third major institutional & service player added to the mix for the first time. The US Army Air Force “Bomber Mafia” in the form of the 20th Air Force and Eighth Air Forces under General Spaatz was to come calling. The “Bomber Mafia” wanted as much of the action as they could get to justify a post-war independent air force and they were not shy in bending the rules or out right lying to achieve their aims, as a detailed examination of the “Operation Starvation” sea mining campaign will made clear. Gamesmanship between the US Army Air Force and the US Navy broke out over the execution of “Operation Starvation” with an eye towards post-war budgets rather than the Invasion of Japan. This competition contributed to the huge Japanese build up on Kyushu by not blocking the smaller wooden hulled Japanese sea traffic moving troops to met the expected American amphibious landing and guaranteed having to repeat the majority of the mining campaign had the war dragged into March 1946.

Historical Background

At the beginning of WW2, The US Army Air Force (USAAF) really didn’t want to do sea mining at all. This was not seen as a “strategic mission” for it’s heavy bombers. MacArthur’s SWPA theater was a perfect example of those bias. General Kenney allowed only a single mine mission with his American B-24 heavy bombers in 1943 using spare aircraft with scratch crews, delivering a total of 24 sea mines. Similarly Admiral Kinkaid, commander of the 7th Fleet, didn’t use any of his PBY Catalina or PV-1 Ventura patrol planes to lay mines. It fell to the PBY patrol planes of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) to fill the SWPA mine laying role for MacArthur the whole war. The most strategically important of those Australian mining raids being a really spectacular night time Manila Bay mission done during the Oct. – Dec. 1944 Leyte Campaign, which was supported by one of MacArthur’s “Section 22” Radio-Countermeasures PBY “Ferret” aircraft.

The US Navy, like the USAAF at the beginning of WW2, was just as disinterested in air-laid sea mining. US Navy Rear Admiral Hoffman in a May 1977 U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings article “Offensive Mine Warfare: A Forgotten Strategy,” described US Navy mine warfare readiness at that time as “pathetic…not much different from that existing at the end of the previous war.” This can be measured by the fact that the total supply of US Navy aerial mines on December 7, 1941 consisted of 200 Navy Mk. 12 magnetic mines, which were based on a German magnetic mine captured by the British, that itself dated from a 1920’s design!

This changed in 1943 due to a triumvirate of officers in the China-Burma-India theater. In February 1943, the Navy assigned Lieutenant Commander Veth to the C-B-I and two other similar mine warfare officers to Admiral Nimitz in the Central Pacific and Adm. Kinkaid in MacArthur’s SWPA theater. Lieutenant Commander Veth became the senior US naval mining officer in the C-B-I. He in turn quickly convinced the theater commander, Admiral Mountbatten and Mountbatten’s air commander, Major General George Stratemeyer of the usefulness of mining. The first UAAF minelaying in the C-B-I occurred on February 22, 1943, when 10th Air Force B-24s laid forty British-supplied mines with 10 planes at the very edge of their useful range. The mines were laid in the Rangoon River to hamper Japanese troops and supplies headed for Burma.

In September 1944 the “A-2” or intelligence officer for the 14th Air Force and his supporting Office of Scientific Research (OSRD) Operational Researchers concluded that sea mines would be the most effective payload for heavy (B-24) or very heavy (B-29) bombers operating from China.

General Claire Chennault of “Flying Tiger” fame seeing this report and the 10th Air Force’s mining success, plus being engaged in a continual transportation campaign against the Japanese Army, began a Fourteenth Air Force sea mining campaign along the Yangtze River between October 1944 and May 1945. This was during the Japanese Ichigo Offensive of April-December 1944 that nearly knocked the Nationalist Chinese out of the war. The effect was to block Japanese steamers from supplying troops fighting inland. Chennault later remarked, “The aerial mine has done more to stop the Japanese drive north from Canton than any other weapon.”

By August 1944 Lieutenant Commander Veth and Major General George Stratemeyer — with the public backing on Admiral Mountbatten who had the twin crises of the Burma “U Go” and South China “Ichigo” Japanese Offensives on his hands — managed to convince General H. H. “Hap” Arnold to allow XXth Bomber Command B-29’s to mine a few Malayan and Indochinese ports prior to the B-29’s leaving for the Marianas Islands. This helped slow both offensives, but not stop the Ichigo Offensive, and more importantly established a precedent of supporting theater commander operations with B-29’s that would be used later.

The lessons of the 14th Air Force operational report; the B-29 mining of Malayan, Chinese and Indochinese ports; plus the success of the 14th Air Force Yangtze River campaign were lost on the institutional USAAF along with their ‘Operation Matterhorn’ B-29 air bases. All these mining’s had been in the “Outer zone” of Japanese sea lanes and not the much shorter and more heavily traveled “Inner Zone” sea lanes that fed Japanese industry raw resources from Japan’s Manchurian, Chinese, Indochinese, and Dutch East Indies conquered territories. The Japanese could and did route around the mines as best they could to avoid ship losses, resulting in unmeasurable by code breaking delays in shipments but no real, measured intently by the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) merchant ship tonnage loses.

Admiral Nimitz and his 7th Bomber Command “Australians”

In the Central Pacific, the US Navy was just as reticent with dropping sea mines from its carrier planes as the Army Air Force was with its heavy bombers. There was just one Central Pacific carrier mission with sea mines, the blockade and strike of Palaus 30-31 March 1944 by Task Force 58 and a further sea mining of Korea by land based Fleet Air Wing One PB4Y-2 Privateers from Okinawa in the Summer of 1945.

Who Nimitz had to do the “scut work” of mining that the Australians did in the SWPA was the 7th Air Force’s 7th Bomber Command. The 7th Air Force was lead by General Harmon of the USAAF. Harmon was a model of a “joint commander.” He was such a real joint commander in a “Bomber Mafia” dominated USAAF that he became unpopular in his own Service the way General Buckner of the 10th Army was General’s Richardson and MacArthur. This unpopularity extended after his death such that he and his contributions first as

1, A theater commander in the South Pacific after Halsey,

2. Later as Nimitz’s commander of all ground based aircraft (USN as well as USAAF) in the Pacific and

3. Finally serving as both commander of the Army Air Forces Pacific Ocean Area (AAFPOA) logistical system supporting the 20th Air Force and as the 20th Air Force’s deputy commander,

are virtually unknown in the historical record of the Pacific War. General Harmon’s wartime accomplishments disappeared as completely from the US Air Force historical narrative as the plane that carried him to his “missing & presumed dead” death.

In the time before his death, General Harmon first ordered PBY’s of his South Pacific Theater to mine islands near Tarawa and as Nimitz’s senior ground based air commander to ordered the B-24’s of his 11th Bombardment group to mine the Bonin Island groups that Iwo Jima was a part of in support of its later invasion. From November 6th to December 18, 1944 the “Project Mike” sea mining offensive in the Bonins pioneered in the USAAF the techniques of dropping of sea mines at night by radar.

Proceeding in parallel with this, the Naval Mine Warfare Section under Nimitz proposed in the summer of 1944 that the B-29’s coming to be based in the Marianas be used to deliver sea mines in great numbers to the Japanese “Inner Zone” home water sea lanes. These reports were given to the newly arriving Chief of Staff of the 20th Air Force, and commander of the XXIst Bomber command, Brigadier General Haywood Hansell. Hansell was one of the “Bomber Mafia’s” intellectual guiding lights and a protege General Arnold. Both Hansell and USAAF Assistant Air Chief of Plans Major General Lawrence Kuter resisted fiercely any diversion of B-29 missions from precision high altitude bombing of Japanese aircraft production. This resistance was supported by General Arnold and Arnold’s Chief of Staff Lauris Norstad.

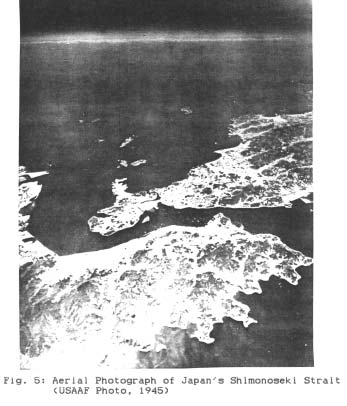

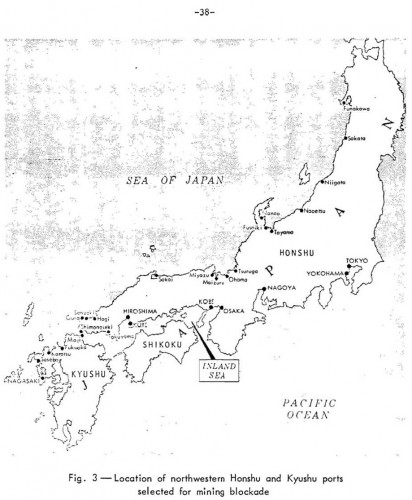

Under Secretary of War Patterson Strong Arms General Arnold

Admiral Nimitz did not take thus “no” from the “Bomber Mafia” as final. He started working both his chain of command and the Civilian-Joint Service “Committee of Operations Analysis” (COA) established by General Arnold to investigate Strategic bombardment issues. The COA, using information forwarded by Nimitz’s Mine Warfare Section, endorsed the idea of mining the Shiminoseki Straits in October 1944. (See picture below) Admiral King, commander in chief of the US Navy (COMINCH), immediately endorsed and forwarded this to General Arnold…and was ignored.

Later in October 1944, a subcommittee of the COA forwarded their own Shiminoseki Straits 5,000 mine mining plan to Under Secretary of War Patterson (See Patterson and his mastery of War Department bureaucracy previously in:

History Friday: US Military Preparations The Day Nagasaki Was Nuked) who also sent a early November 1945 letter to Gen. Arnold, which he could not ignore. He didn’t. But Arnold could and did kick the question to his air staff, so as to delay an answer to Late November 1944. This response was a reiteration that air superiority, by bombing Japanese aircraft factories, came first.

The Sea Mining Iceberg Breaks

Then in November 1944 there arose a _NOT UNREASONABLE_ fear in the Washington DC senior air staff planners that if they didn’t do the sea mine laying mission, that War Department civilian leaders like Under Secretary Patterson, or worse, the very pro-Navy President Roosevelt, might allocate a number of B-29’s to the US Navy to accomplish the mission. The War Department had earlier in the war allocated B-24 to anti-submarine patrolling over strategic bombing. That fear, how ever it was arranged (Perhaps by Patterson?) “Broke the Iceberg” of resistance the “Bomber Mafia” had to mining Japanese home waters.

This USAAF senior air planning staff fear not only moved Arnold in December 1944 to support a small (one B-29 Group) mining effort starting in April 1945. It further motivated him into providing B-29 mission support for Pacific Theater commander Admiral Nimitz’s proposed “Operation Iceberg” invasion of Okinawa. This was very much over the strong objections of General Hansell, commander of XXIst Bomber Command. This was beyond what Arnold was required to do under the Joint Chiefs authorization that created the 20th Air Force and was a good indicator as to how seriously Arnold viewed the sea mining mission threat to his USAAF B-29 monopoly.

Hansell’s continued resistance to sea mining also spotlighted for General Arnold the other problems the 20th Air Force’s XXIst Bomber Command was having. High altitude precision bombing was not working and its failure with Japan would jeopardize a post-war independent air force. Technical issues with the B-29 and the high altitude jet stream winds combined to thwart effective high altitude bombing of Japan. Hansell was already on, -Ahem-, thin ice with Arnold for those issues plus Hansell’s failure to vigorously follow up on various incendiary vulnerability reports from both the Air Staff and the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) and some very pointed hints from Arnold’s Chief of Staff Lauris Norstad that Arnold wanted incendiary attacks on Japanese cities. Sea mining objections could well have been the straw that broke the camel’s back in terms of Arnold’s command confidence in Hansell. So in January 1945 General ‘Hap’ Arnold selected General Curtis LeMay to relieve Hansell at XXIst Bomber Command.

LeMay, like Kenney, really didn’t like to drop mines from his B-29’s very heavy bombers. In the Pacific, he was not going to have the choice. He had specific orders to mine, and like with first Mountbatten in SEAC and later Nimitz in the Central Pacific, theater commanders were leaning on LeMay through his logistics to get him to drop mines.

While the Chinese harbors LeMay mined for Mountbatten didn’t have a decisive effect, the Japanese Home Islands were a different story. Japanese shipping lanes there were densely packed with untouched merchant traffic as compared to other areas. Sea mines there, as the US Navy had predicted, caused a disproportionate number of ship kills and huge industrial disruption. This was immediately apparent through Ultra intercepts and photographic reconnaissance in the late war. So if LeMay was going to do drop mines, he was going to do it effectively. And effectively for Lemay meant using a whole wing rather then a single group.

Lemay unlike the “Boy Generals” surrounding Arnold was a pure operator. And also like the generation older Arnold, he did not attend the “Bomber Mafia’s” air tactical school. He didn’t care for the Daylight Precision bombing doctrine the way the “Boy Generals” did. Lemay cared for the metrics the “Boy Generals” established. Those metrics were tonnage delivered, planes lost, and targets destroyed. And in the Operation Starvation sea mining campaign, he gamed those metrics for all he was worth.

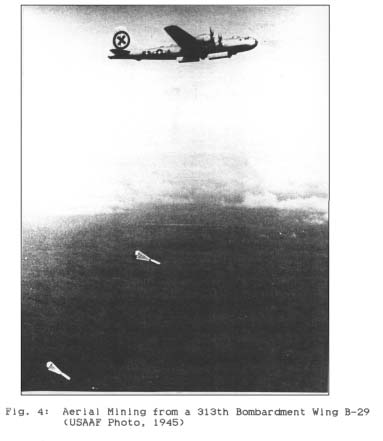

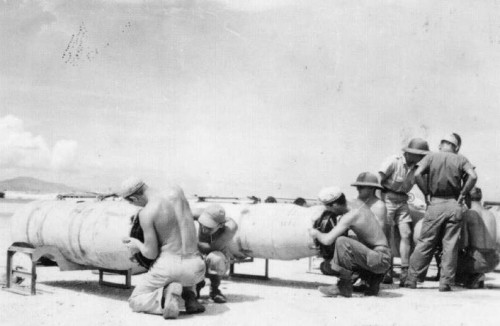

He chose for the mining mission the 313th Wing. A rookie outfit just arriving from the USA for the first mining mission and he chose to use the same low level night time, formation-less attack profile as his Tokyo fire bomb raids. This would let his rookies fly an easy profile to maximize tonnage with minimum losses with an easy radar target. (See radar image below)

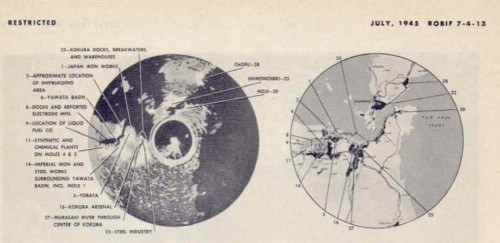

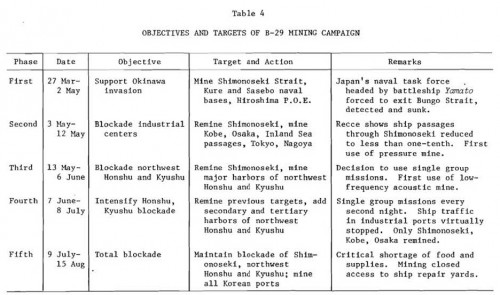

After the first wing sized mission that established the “Mike” and “Love” mine fields on either side of the Shimoseki Straits, LeMay moved to a every other night remining effort with the single group. This simplified his planning and execution of the mining mission, and it also gave the Japanese an easy pattern to track mine drops and sweep them. He then switched between wing sized and group sized mining efforts based on a phased plan to blockade Japanese ports. (See photo below)

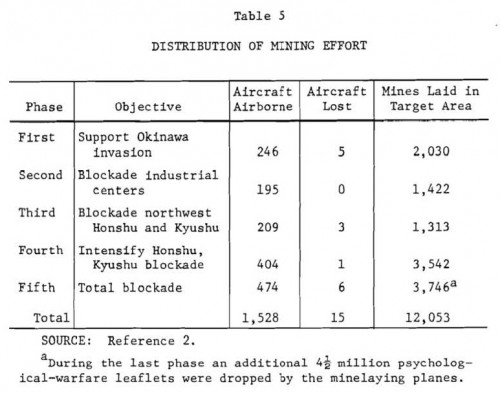

There then proceeded to be -a lot- of fun and games with sea mine fuze setting because the USAAF wanted to kill ships larger than 500 tons for reasons of wartime metrics and post war budget. This was not at all helpful for the proposed invasion of Kyushu given that all Japanese mine sweepers and three out of five hulls in Japan’s inter-coastal waterways were in that 499 tons or less category. (I strongly suspect, but cannot prove a through research yet, that the general outlines of the impending JANAC gerrymander line were known to USAAF CoS General H. H. “Hap” Arnold and through him to LeMay.) You can see in terms of the total number of mines dropped in the final phases of the campaign below that LeMay was going for the kill in terms of numbers. (See below)

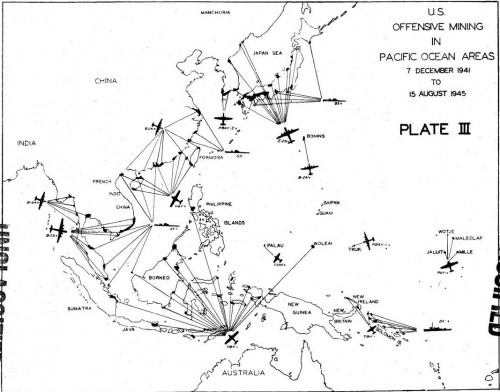

And also in terms of ports, as the ports on the western shore were struck at the end of the campaign to cut off food shipments from Korea and China. (See Map below)

But most importantly in terms of hulls killed, as this passage and table from the April 1974 Rand Study “Lessons From an Aerial Mining Campaign (Operation Starvation)” by Frederick M. Sallagar below makes clear:

One of the key decisions made by the XXI Bomber Command when planning the campaign was “to select for sinking the larger ships of the enemy’s fleet.” The desire to destroy as much enemy ship tonnage as possible runs throughout the official report on the campaign.

.In order to correct the defects and weaknesses of the standard Mll and M9 Mod 1 magnetic and A-3 acoustic mechanisms , local modification of these mechanisms was proposed to accomplish two things: First, and most important , to defeat the known enemy sweeps, and, second, to select the largest enemy ships for sinking, so as to obtain maximum damage on a tonnage basis.*

.

Or again:

.More than 60 percent of this {Japanese] shipping was composed of ships with a size of 4000 gross tons or larger. These large ships were the prime targets, and one of the mining problems was to sink ships selectively. One mine could sink or seriously damage one 10,000 ton ship at ten t imes the profit that would be obtained if the same mine sank or damaged one 1000 ton ship.

.

The planners clearly were concerned with ship sinkings not solely as a means of enforcing the blockade but as an end in itself.

![Operation Starvation Ship Tonnage Sunk [made up of 500 ton(+) ships] -- Source: Apr 1974 Rand Study "Lessons From an Aerial Mining Campaign (Operation Starvation)" by Frederick M. Sallagar](https://chicagoboyz.net/wp-content/uploads/Rand-Operation-Starvation-1974-Table-8-500x498.jpg)

The US Navy also had its own fun and games with mine and their fuses. First, US Navy mines, unliked those of the Germans and British, did not have self-destruct anti-tamper fuses. Any mine dropped on land the Japanese could rapidly disassemble and examine for counter-measures. Only Japan’s dysfunctional military command structure and desperate condition under firebombing prevented a much more successful anti-mining effort.

Second, after the Shimonoseki straits between Honshu and Kyushu were mined in March 1945 with “forever deadly” fuze setting. The US Navy then changed all the mine fuze “self-neutralize” time setting to a range of dates from January to February 1946. Since the Operation Downfall plans called for the invasion of Honshu to happen in March 1946, you can see the problems.

Also, because the US Navy did not plan months ahead for the extent of the mining campaign with sufficient shipping priority, given the Operation Olympic Invasion build up. Neither the sea mines, nor the fuzes for them, were arriving in sufficient quantity to allow any real mission planning on the part of the Naval Mine Warfare Teams nor the 313th Bomb Wing.

In order to maintain the mine blockade through the whole of the planned Operation Downfall invasions period either LeMay or Kenney would have to repeat virtually the entire mining campaign right before the invasion of Honshu. And the US Navy did not give sea mines the shipping priority to repeat the job! That was as strong a wartime statement of how long the US Navy thought the war with Japan was going to last as I have been able to find in my Pacific War research to date.

Impact of Mining Campaign on Japanese Merchant Fleet

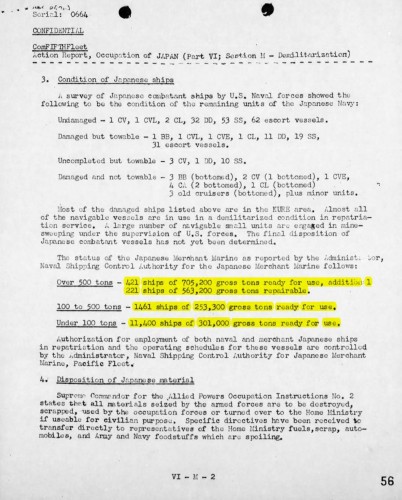

There was a huge issue with the concentration by the US Navy and USAAF on killing large ships, and one that was not limited to making Japanese mine sweeping more difficult. When you investigate the demilitarization section of FIFTH FLEET Action Report, Occupation of JAPAN Aug 15, 1945 thru Sept. 8, 1945, you find an eye opening distribution of Merchant Marine vessels by size.

There were

o 642 ships larger than 500 tons with 1.268 million gross shipping tonnage (GST),

o 1461 ships between 500 and 100 tons with 253, 000 tons GST and

o 11,400 (!) ships under 100 tons with 301,000 GST.

See document photo below:

There were more than 12,800 ships and boats below 500 tons displacement that could move men by tens and by 100’s without tripping an American sea mine. General MacArthur needed a blockade that could stop those vessels from moving troops to have a successful Operation Olympic landing.

He did’t get one.

The USAAF and US Navy’s concentrating on killing large ships JANAC counted meant that smaller wooden Japanese ships could move large numbers of people to small ports and beaches not mined by the B-29’s. The Japanese putting together a concentration of 15% of those small craft after the loss of Okinawa would mean 1920 vessels times, say, 15 troops per lift, works out to 28,800 troops! Repeat that for seven night time round trips and you are talking 201,600 troops in a week!?!

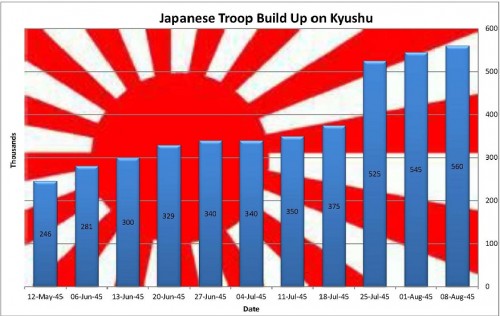

Does the historical record support that range of numbers? Both in terms of Japanese ships sunk and in terms of Japanese troop movements? The answer is yes.

The table below is drawn from wartime Ultra code breaking (NSA History Document SRH-195). Look closely at the troop number jump between between 18 July and 25 July 1945.

The table makes clear that the issues of American inter-service politics was going to dominate any invasion of Japan, if the A-bomb had not ended the war. And in fact, it was those dysfunctional politics that had dominated the war to the point that it made the use of the A-bomb inevitable.

Now you know why the diplomatic and military academic history communities won’t go near this narrative.

Source and Notes:

John S. Chilstrom, “MINES AWAY! THE SIGNIFICANCE OF U.S. ARMY AIR FORCES MINELAYING IN WORLD WAR II,” Thesis, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, May 1992

Robert C. Duncan, America?s Use of Sea Mines (White Oak, Maryland: U.S. Naval Ordnance Laboratory, 1962).

The author, former Chief Physicist for the U.S. Naval Ordnance Laboratory, gives the total supply of aerial mines on December 7, 1941 as 200 Navy Mk. 12 magnetic mines. It was the only American mine which could be air delivered at the start of the war. The Mark 12 was based on a captured German magnetic mine, which itself was a 1920’s design. According to Duncan, “It could be handled only from wing or torpedo racks, and few types of long range aircraft were available for minelaying.”

FIFTH FLEET Action Report, Occupation of JAPAN Aug 15, 1945 thru Sept. 8, 1945 (Part VI ; Section M – Demilitarization) Page VI-M-2 (56)

Hoffman, Roy F. “Offensive Mine Warfare: A Forgotten Strategy.” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings

103 (May 1977): 142-155.

Note — Rear Admiral Hoffman described mine warfare at the beginning of World War II as “hampered and diluted by poor preparedness.” He called readiness “pathetic…not much different from that existing at the end of the previous war.” Hoffman was also critical of the U.S. failure to adopt a strategic mining plan until the last year of World War II.

Ellis A. Johnson and David A. Katcher, Mines Against Japan (White Oak, Maryland: U.S. Naval Ordnance Laboratory. 1947; reprint, 1973), 41. Also, see Boyd and Rowland, 159.

The authors describe US Navy mine development from 1918-1939 as “virtually dormant” due to the very small staff provided the Naval Ordnance Laboratory (NOL). British experience with German magnetically fused sea mining caused an expansion, but the Lab’s priority went to countermeasures, defensive mines, and then to offensive mines.

Lott, Arnolds. “Japan’s Nightmare- Mine Blockade.” us Naval Institute Proceedings, November 1959, pp. 39-51.

Operation Starvation

http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA420650

During Operation STARVATION, more than 1,250,000 tons of shipping was sunk or damaged during the last five months of the war. Approximately 12,000 mines were laid requiring only 5.7 percent of the Twenty-first Bomber Command’s total effort. Out of 1,529 B-29 mining sorties, only 15 aircraft failed to return.

“Report of the Surrender and Occupation of Japan, US Pacific Fleet, 11 February 1946”. DTIC Accession number — ADA438971

Page 60

Cominpac (Rear Admiral Struble) had information that the harbors and approaches to Moji and Shimonoseki contained 3000 live influence mines, 1200 of which were the pressure type–which cannot be swept, the only means of testing an area suspected of containing pressure mines being to employ “guinea pig” ships. According to the sterilization dates given on the TWENTIETH Air Force mine charts, which were calculated to be the last dates on which the sterilizers would act, these pressure mines would become sterile by 17 February 1946, with most mines sterilizing 20 to 30 days before that time. A small percentage would fail to act, leaving the mines alive and dangerous. This would necessitate a post-sterilization sweep, but the risk by then would be materially lessened, and the loss of sweeping gear due to mine explosions would be greatly reduced.

Page 70

Mine Operations-

Of the 17,285 mines laid by Army and Navy aircraft, some 12,000 were dropped by B-29s of the 20th Air Force, principally in Japanese home waters. Of this total, 41% were magnetic type, 29% were acoustic type 24% pressure-magnetic type, and 6% were low frequency type. These influence mines were developed by the Navy, and prepared by Mine Assembly Depots on Tinian and Okinawa. Subsequent to the first two missions of the B-29s, all of these were equipped with sterilizers, rendering the exploding mechanism dead after a given period (15 February 1946 for B-29 laid mines). For this reason, the influence mines have not been swept to the same extant as the Japanese mines.”

Frederick M. Sallagar, Lessons from an Aerial Mining Campaign (Operation “Starvation”), Report R-1322-PR, (Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, April 1974)

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey Pacific War, Naval Analysis Division, “The Offensive Mine Laying Campaign Against Japan,” Washington: 1 November 1946.

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey Pacific War, Transportation Division, “The War Against Japanese Transportation 1941-1945,” Washington: May 1947.

War Department (MID) Military Intelligence Service Japanese Ground Forces Order of Battle Bulletins (9 June – 11 August 1945) DE SRH-195 (Part II)

The British have for years accused the US Armt of ignoring mines in land warfare (See for example Max Hastings’ book on Normandy). This seems to ignore the difference in philosophy between the two armies. The US was focused on offensive operation and the British, as at el Alamein, in defensive formations. The US used plenty of mines in the Ardennes campaign where defense became critical.

It’s interesting to see the CBI theater role, which was of course a British command.

MikeK,

The funny thing is that today in terms of mines — thanks to the AP Land mine ban Ottawa treaty — the reverse is true between the USA and UK.

A couple of things stood out for me after researching and writing that piece. First, when it comes to the measure of confirmed kills versus blockade, the US high command had a measure of effectiveness with Ultra troop numbers and B-29/F-13 photo-recon coverage. The problem was the commander most concerned with that that metric — MacArthur — didn’t have the same level of authority over the means as Eisenhower did in Europe. Ike had both the navy and strategic air forces under his direct command for Operation Neptune.

That was a Presidential/JCS level screw up…which is another strong reason American the Diplomatic and Military academic historians won’t go near this.

Second, the Mahanian US Navy had a real problem with littoral sea power — small ships and craft — in any form.

Consider for a moment that the US/UK LCI(L)landing ship (see http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ships/ships-lc.html and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landing_Craft_Infantry) was roughly 400 tons displacement fully loaded and moved a full infantry company. A total of 36 of them would move the nine infantry battalions of a full triangular infantry division.

The US Navy converted 100 of them to gunboats in the Pacific — 27 infantry battalions worth of sea lift(!) — by war’s end and wanted to do that to another 100 LCI(L) in MacArthur’s 7th fleet.

This is the face of the demonstrated need to disperse long distance troop lift in the face of the Kamikaze threat that Admiral Barbey sent star shells to Admiral Turner after the Leyte Campaign about…and was ignored for Operation Olympic shipping plans.

The staff officers of the US Navy Central Pacific fleet often gravely underestimated what hulls of under 1000 tons displacement could do for the Japanese as short distance, fast turn around, combat ferry’s and that showed with their B-29 mining campaign choices.

For an example see the Japanese Type 101/103 landing ship:

HIJMS Landing Ship T101 Nito Yuso Kan Diesel

http://navalhistory.flixco.info/H/261414/8330/a0.htm

T-101 Class, Japanese Landing Ships

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/T/-/T-101_class.htm

Japanese landing craft Type 101 in Kure Harbor after the Japanese surrender 1945

http://www.flickr.com/photos/16118167@N04/9423463038/

No.101-class landing ship, No.103 class landing ship

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No.101-class_landing_ship

No Japanese Army records of the Type 101/103 in their service survived the war and there were nine of these — some converted from oil to coal fired(!) — in service in Japanese home waters plus some number of IJN Type 101’s.

Here are examples of the cargo capacity of one of these vessels:

120 troops, 22 tons freight or

Example 1: 13 × Type 95 Ha-Go (light tank)

Example 2: 9 × Type 97 Chi-Ha (Medium Tank)

Example 3: 7 × Type 2 Ka-Mi (Amphibious Light Tank)

Example 4: 5 × Type 3 Ka-Chi (Amphibious Medium Tank)

Example 5: 220 tons freight

Example 6: approx. 280 troops

By aiming their mines against larger hulls, the USAAF and US Navy gave the Type 101’s a free ride. This is what the U.S. NAVAL TECHNICAL MISSION TO JAPAN said of the Japanese design intent with the Type 101 landing ship:

It would appear that the Japanese Naval staff were spot-on regards their design goals, at least as far as the naval mine fuse setting used by the USAAF and US Navy Mine Warfare people were concerned.

The USN was getting rid of the LCIs as troop carriers precisely because they had proved highly vulnerable in action to all forms of attack including aircraft, and they were not effective at landing troops under enemy fire, nor could they handle difficult beach conditions, you can look at those ramps for 1 minute and see why. They were not capable of long distance troop transport under realistic conditions, as the LCI was only designed to cross the English Channel carrying follow on forces, not broad Pacific distances. Troop accomidations were very poor, which leads to poor combat effectiveness upon landing.

It could not carry vehicles, nor heavy weapons and equipment that were not man transportable, making it impossible for them to directly replace attack transports. You cannot land an infantry battalion from an LCI with all its gear. Meanwhile numerous Pacific landings had shown a need for more close fire support for other forms of landing vehicles, a need that could only be met in the required numbers in the required timescale by converting large numbers of existing craft. The USN made this call based on three years of extensive amphibious experience. See Friedman’s US Amphibious Ships for a very detailed discussion of the matter. Great call was out for more gunboats, and mortar boats and rocket boats.

The mining campaign was designed to stop the Japanese economy, what sense does it make to first try to stop troop movements when the Japanese already had far more troops then he had weapons or ammunition? Stopping production of said items first was the correct decision, leaving the infantry as largely cannon fodder. For that matter what sense would it make to sink small craft, but leave the big ones to carry much greater tonnages? Destruction of small craft was a job best suited for tactical aircraft and navy flying boats which could relentlessly hunt them down, and that destruction would have stepped up rapidly as more and more fighter groups became operational on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, as well as continued and ever more intensive raids by fast carriers. The USAAF was also in the opening stages of an extensive campaign against the Japanese railroad network when the war concluded, destruction which would have forced far more economic traffic into coastal shipping and further burdened it even as it began to be destroyed.

I’m really not sure what the point of this entire article is except to criticise the USAAF for not having unlimited resources at its disposal when it was still months away from fielding its planned order of battle for Operation Olympic. The rather large RAF force meanwhile had barely begun to even arrive.

Rob,

I advise you to go read the “Seventh Amphibious Force, Command history, 10 January 1943 — 23 December 1945” regards what the LCI(L) could and could not do.

What the Central Pacific fleet thought and wrote of the LCI(L) had very little to do do with how it actually performed in combat in the SWPA.

See this link for an HTML version of the 7th’s command history:

http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/7thamphibcomdhist.htm

Or this link for a PDF file:

http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p4013coll8/id/3174/rec/1

Pay strict attention to the Task Organization, Ormoc Operation, 7 December 1944, Ref: CTG 78.3 Attack Order No. 5-44. That was the invasion fleet for the 77th Infantry Division that closed the Leyte campaign in a littoral sea, under a Kamikaze filled sky.

There was not a single APA or AKA for a seven infantry battalion (Division minus with attachments) sized landing. There were eight APD, 27 LCI(L)’s and four LST.

See also RADM William ’s TG 78.2 at the 21 January 1945 Nasugbu (‘Mike Six’) landing with the glider regiments of the 11th Airborne Division. Fechteler was following the established 7th Fleet/6th Army amphibious force protection doctrine.

SWPA amphibious ships & craft always loaded light, with vehicles filled with supplies on LSM & LST’s for quick debarkation at roughly 0730 to 0830, and a very quick withdrawal (often by 1200) compared to Central Pacific amphibious assaults which _started_ at 1030 after lots of intense shore bombardment and air strikes.

This was due to SWPA assaults generally having only contested local air superiority from distant land bases, as compared to pure air supremacy from local carrier task forces in the Central Pacific drive, with no prospect of replacement amphibious shipping if lost.

TG 78.2’s landing ship force structure of four APD’s, 35 LCI’s, eight LSM’s, and six LST’s is also very much Adm Barbey’s preferred one for avoiding the presentation of “troop lucrative” targets like AKA and APA to Japanese air attack and Kamikaze strikes in particular. Barbey makes a specific observation about that in his 1969 book “MacArthur’s Navy” pointing out thw official “lessons learned” feedback from him to Admiral Turner the Philippines Leyte & Luzon campaigns for the invasion of Japan.

Turner’s reaction to that feedback — as implimented in the Operation Olympic shipping plans — was an interesting case study of “believe what you wish to believe, and damn the evidence.”

Another great article. I remember being a kid and reading “Silent Victory” by Blair about the role of the submarines in the Pacific and feeling that they were highly slighted by history. Whether that’s really true or not, I’d leave up to you, but it fits our glamorous view of the heavy bomber and the large surface ship that would supposedly dominate the enemy.

PV-1 was a Ventura

[Author Note — Fixed]