In my last column I spoke of the impact of the US Navy’s visual communication style on the night fighting in the Solomons, and how it negatively impacted the “Black Shoe” surface ship officer’s ability to adapt to the radar and radio centered reality of night combat with the Imperial Japanese Navy. This column will explore how this communication style impacted the use of LVTs, or “Landing Vehicle Tracked” at Tarawa, and compare and contrast how that style interacted with how the US Army and US Marine Corps approached fighting with LVTs later in the Pacific War, and what it meant for the future.

THE BLOODLETTING

The assault on the island of Betio, in the Tarawa atoll, was the worst 76 hours of bloodletting in the history of the USMC. In the words of Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret):

The final casualty figures for the 2d Marine Division in Operation Galvanic were 997 Marines and 30 sailors (organic medical personnel) dead; 88 Marines missing and presumed dead; and 2,233 Marines and 59 sailors wounded. Total casualties: 3,407. The Guadalcanal campaign had cost a comparable amount of Marine casualties over six months; Tarawa’s losses occurred in a period of 76 hours. Moreover, the ratio of killed to wounded at Tarawa was significantly high, reflecting the savagery of the fighting. The overall proportion of casualties among those Marines engaged in the assault was about 19 percent, a steep but “acceptable” price. But some battalions suffered much higher losses. The 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion lost over half the command. The battalion also lost all but 35 of the 125 LVT’s employed at Betio.

The Marines lost roughly 333 men killed a day, or 13.25 men killed an hour for every hour for the assault at Betio. And for every man killed, two more fell wounded.

There were a number of reasons for this. The standard narrative speaks to inadequate naval fire support and bombing by the air forces of the Army and Navy, of Betio being surrounded by reefs that cut off the LCVP Higgins boats from the island, save at high tide, and a once in several decades “super neap tide” — where the combination of a strong solar perihelion tide, weak lunar apogean tide plus the expected last-quarter moon neap tide could combine for a no-tide period — that prevented the high tide from rising enough, thus forcing troops to cover hundreds of yards of machine gun and artillery swept shallows just to get to shore.

This was why General H.M. Smith insisted that Tarawa have LVTs — despite Operation Galvanic amphibious force senior commander Admiral Turner’s objections that he could not control or coordinate the landings with LVTs — or Smith as ground force commander would cancel the operation because the invasion would fail without them. History has judged General Smith’s verdict as correct.

History, however, at least in terms of the standard institutional narratives, glosses over the fact that Admiral Turner was also correct. And the reason why was the US Navy’s interwar love-hate relationship with radio that was rocking the centuries-old visual communications traditions of the chief American naval service.

THE BACKGROUND

The US Navy going into World War II (WW2) was the predominant technological fighting service in America and justly proud of its radio and other communications systems. The problem was that electronic technology was rapidly outpacing its traditions, its leaders and its development bureaucracies. The TBS and TCS radios its bureaus developed were amplitude modulated Voice/Morse code equipment built for talking between ships, not for open top boats or amphibious vehicles. When soaked by sea water they failed to operate until dried out. When operated close to unshielded internal combustion engines — unlike the new US Army frequency modulate radios developed for Army vehicles and artillery — they heard the electrical noise from the spark plugs which made them extremely full of static. Besides, small open boats were the province of naval coxswains who knew the naval signal lamp and semaphore flag codes.

LVTs run by US Marines at Tarawa had neither armor, nor radios, nor any coxswain type training in the US Navy’s visual communications those three bloody days in November 1943.

When the LVTs of the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion left the line of departure to run over the reefs and onto Betio’s beaches, they were no more able to exercise control than a horse cavalry charge…and a lot slower. This slowness meant that the five minute gap between the stopping of the naval bombardment stretched to 15 minutes, with no way to extend covering naval gunfire, and the 3,000 Japanese Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) Marines had time to come out of their bunkers and fox holes to man heavy weapons. During those three days the LVTs of the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion made run after run across the atoll’s shallows trying to bring in more Marines across the death ground…and more and more LVTs died learning the lessons of the need for radio command and control.

LESSONS LEARNED…DIFFERENTLY

The next major LVT landings after “Blood Betio” were the January 1944 Operation Flintlock landings in the Marshall Islands. These landings underlined the differences between the US Marines as naval assault infantry and the US Army as the premier continental ground combat service. Assault infantry are sprinters. They do tough frontal assaults on fortifications, and other difficult terrain attack missions, quickly with the minimum of heavy weapons. They are, by their very nature, short term thinkers. Quite literally if Assault Infantry doesn’t get the short term right, there is no long term.

The US Army, as the dominant ground fighting service, works on both a larger scale and a longer term basis. Its world view makes planning, logistics, engineering, signals and the use of large numbers of heavy weapons the center of its fighting style.

When handed the same weapon, the LVT, during Operation Flintlock, these institutions organized to use it differently, reflecting their different traditions.

The Marines took the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, which had sent one officer and fifty men to pilot LVTs of the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion, and used them as cadre for raising two more amphibian tractor battalions plus a company (A total of nine companies from four original companies) for the landing at Roi-Namur. And it took those nine companies into combat 30 days later. To quote the Marine author of the definitive development history of the LVTs in WW2:

The net result was to produce an undertrained LVT organization for an operation that was tactically more complex than any previous landings attempted in the Central Pacific.

It got worse in that the radios these ill-trained LVT units tried to use were the US Navy standard TBS/TCS radios, which to quote from COMINCH P-002, AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS, THE MARSHALL ISLANDS, JANUARY – FEBRUARY 1944:

TCS radio equipment in LVT-2s and LVT(A)s were quickly drowned out by spray despite their having been provided with canvas covers, This type of craft is very wet and requires a watertight radio set.

These problems resulted in multiple miscues controlling the LVTs during the Roi-Namur landing operation that were only redeemed by the much better US naval gunfire preparation and the fact that Japanese defenses faced the sea and not the inside of the lagoon where the LVTs chose to land.

THE ARMY SHOWS THE WAY

The US Army’s 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, assaulted Kwajalein during the same operation had much different results.

Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison’s histories raved about how well the US Army’s 708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion did using LVTs in comparison to the 4th Division’s LVT units. To again quote from COMINCH P-002:

PAGE 153 OF 184

The 7th Infantry Division so organized its amphibian tractor units that it was able to retain desirable tank operational and maintenance procedure and technique and at the same time fit the organization to its new functions.

And page 154 OF 184

Within each LVT Group, one LVT was employed solely for emergency maintenance and repair. This LVT carried extra gas and oil, a small supply of spare parts, a welding outfit, extra plating and a maintenance crew. It operated between the line of departure and the beach and rendered immediate assistance to any tractor in difficulty or which suffered damage which the crew itself was unable to repair.

For purposes of coordination and command, the Battalion Commander of the Amphibian Tractor Battalion was located in the flagship of the Transport Group Commander. His executive officer was located in the flagship of the LST Group Commander. By this arrangement the LVT Commander could maintain close, direct and personal contact with the troop and naval commanders with whom he had to work and, through his executive officer, issue instructions directly to his LVT groups.

During the ship to shore movements the LVT Battalion Commander moved to the line of departure and remained on or in the vicinity of the control vessel. Through the control vessel he could readily communicate with the transports, the LST’s or with the beach and from his position near the line of departure could observe and supervise the operation of his LVT groups.

By the methods and technique employed as outlined above, the 708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion operating in four LVT groups from eight LST’s was able to execute five separate landings on schedule. No LVT’s were swamped or lost in the surf. Two LVT’s were swamped as a result of attempt to tow at a speed in excess of ten knots. None were seriously damaged by hostile fire. All LVT mechanical failures or hull damages were repaired and the tractors returned to service without delay. All LVT groups operated at full strength throughout the operation.

Due to LVT shortages the 708th had the same issues training its troops as the Marines, and it had to use 7th Division cannon company troops to man many of its LVT tractors for the invasion. Yet it did so much better. Why?

To start with, this “provisional” unit was teamed with one of the best US Army amphibious commanders of the war and the 7th Infantry Division was a veteran of both the US Army’s Amphibious Training School — which trained it in the US Army’s radio based “Shore-to-Shore” landing techniques — and the invasion of Attu, Alaska.

Next, the 708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion was a converted US Army independent tank battalion built to support US Army infantry divisions. Everything it did per the passage above was standard operating procedure for US Army independent tank units, which had had “Shoot, Move and Communicate” in its organizational DNA, preventive maintenance as a secular religious catechism, and had liaison with infantry as its reason to exist. Unit for LVT unit, Army troops could drive and swim father, for longer, and more flexibly than the Marines. And it did all of that with FM Radio, a radio type not native to the US Navy. For a given vehicle equipment set, the Army was simply better organized and trained to get the most from it.

This relative level of LVT performance continued, but both Army and Marine LVT units had to be trained to conform to the Navy’s visual communications style after the Marshalls campaign. This slowed down the Army radio based “Shore-to-Shore” LVTs to Navy/Marine visual communications based “Ship-to-Shore” speeds for the balance of the Central Pacific campaign. There was however, one shining moment during the Leyte campaign where that was not true.

THE FORGOTTEN GLORY OF ORMOC

In the latter days of the Oct Dec 1944 Leyte campaign two veteran Central Pacific US Army Divisions, the 7th and the 77th Infantry Divisions, cut loose with their LVTs in the sort of “Shore-to-Shore” operations that the US Army Amphibious Training School foresaw years earlier.

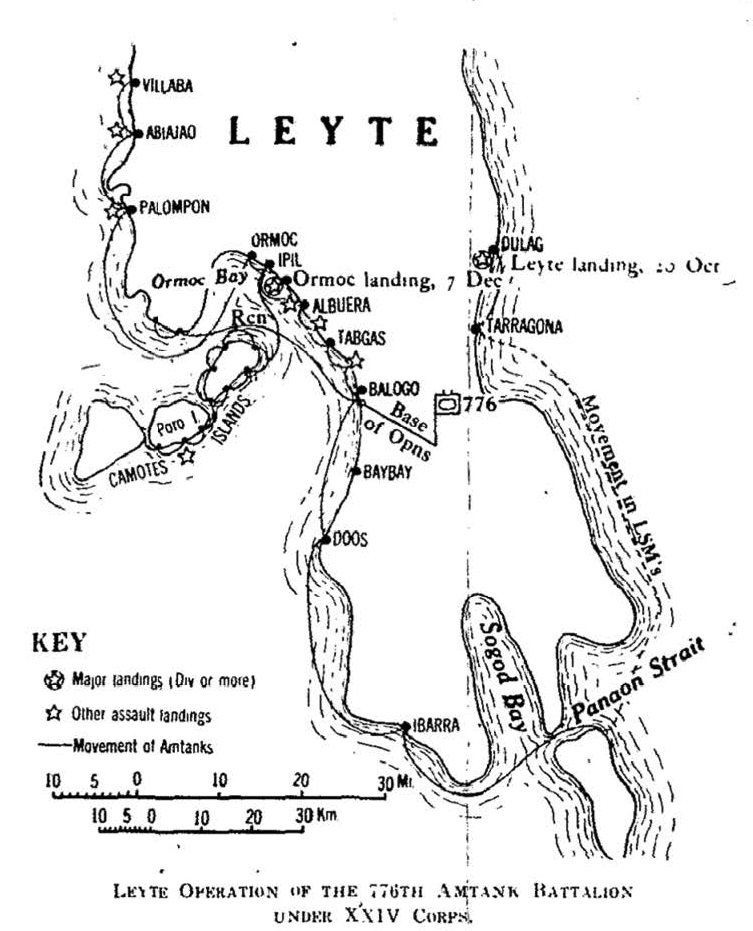

At the behest of General Douglas MacArthur’s Sixth Army commander, General Walter Krueger, the US Army’s 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion was shipped from Tarragona in Eastern Leyte by 7th Amphibious Force LSM amphibious ships to South Leyte’s Panaon Straits. Then, to preserve the amphibious ships from Kamikaze attack, it moved by sea under its own power to Ibarra and laid over a night. It then moved to Doos, laying over a 2nd night and then finally joined the 7th ID south of Balago on the West Coast. The next few days it did “Sea cavalry” raids behind Japanese positions shelling them with its 75mm howitzers in support of the 7th Infantry Division’s northern advance.

On one of the last of these raids the 776th was nearly run over by the 77th Infantry Division’s amphibious shipping south of Ormoc, where the 77th was to land. (Someone always misses the last word.)

In the days that followed, the XXIV Corps placed elements of the 776th under the 77th Division to stage a final “Shore-to-Shore” landing from Ormoc to the last Japanese port in Leyte, Palompon, and to clean Japanese hold outs from the Camotes Islands West of Leyte.

OKINAWA, THE A-BOMB, AND THE FUTURE

The last major amphibious campaign of Okinawa in April-June 1945 did not see the large scale “maneuver from the sea” by LVTs. Though there were many smaller landings as well as the large landing on Okinawa proper. The US Navy stuck to its “Ship-to-shore” visual communication style landings throughout.

This changed with the end of the Pacific War and the arrival of the A-bomb. A massive change had to occur in US Navy amphibious doctrine to be able to adopt the faster, more night time and radio based “Ship-to-shore” methods. The Navy had to scrap its visual communication style because it just wasn’t fast enough in the face of the threat that one A-bomb could kill one amphibious landing.

The US Army, on the other hand, forgot everything it had learned in the Pacific and more. General Marshall’s European commanders took over the US Army and remade it in their image. There was no room for LVT battalions in the active Army. That was the Marines’ and Navy’s job.

Actually, it wasn’t, as the US Navy budgets had run down the Marines’ LVT fleet to little more than well preserved vehicle parks in the California desert, because it hadn’t solved the A-bomb dilemma.

It took MacArthur’s victory with a Marine brigade armed with left overs at Inchon, Korea in the early 1950s to close the Tarawa era of US Navy visual amphibious communications, and open a future for the Marines based on the US Army’s Leyte past.

Notes and Sources:

Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret), ACROSS THE REEF: The Marine Assault of Tarawa

The Significance of Tarawa

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003120-00/sec8.htm

Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, “Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa” Naval Institute Press, c 1995, ISBN: 1-55750-031-2 See Page 76.

Major Alfred Dunlop Bailey, USMC (Retired), “ALLIGATORS, BUFFALOES, AND BUSHMASTERS: THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE LVT THROUGH WORLD WAR II,” HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION, HEADQUARTERS, U. S. MARINE CORPS, WASHINGTON, D.C, © 1986

MAJOR JOHN T. COLLIER, “DEVELOPMENT OF TACTICAL DOCTRINE FOR EMPLOYMENT OF AMPHIBIBIAN TANKS,” Military Review, October 1945, pages 52 – 56

COMINCH P-002, AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS, THE MARSHALL ISLANDS, JANUARY – FEBRUARY 1944, CARL Digital Library

Norman Friedman, “U.S. AMPHIBIOUS SHIPS AND CRAFT: AN ILLUSTRATED DESIGN HISTORY,” Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, © 2002, ISBN 1-55750-250-1 page 217

Interesting piece. I had read about the Betio landings but didn’t know about the LVT vs Higgins boat issue. Tarawa was also, I think, the first opposed landing for the Marines as the Japanese did not contest the Guadalcanal landing, although I guess there was some opposition at Tulagi.

It is my understanding that the number one request from troops that made it ashore was radios, radios, radio batteries, and more radios. The LVTs were almost not taken due to their late arrival and the troops had little time to train and only were able to weld boilerplate to the sides as protection. Yet, they made a huge difference. The first wave actually got inland before the Japanese recovered from the bombing.

An interesting side-note is that Eddie Albert, (Green Acres), was on the destroyer that actually went into the lagoon on its own initiative due to lack of communications. They may have saved hundreds and even changed the momentum of the battle.

Ronald,

Destroyer into the lagoon? Whoa, what’s the draft and the MLLW in there? Any links to the story?

Trent,

I am so looking forward to the book you write out of all this.

Never mind, I found it: USS Ringgold. http://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/slugging-it-out-in-tarawa-lagoon/

To paraphrase something someone once said: “Where do they find these kind of men???”

(And huge bonus points to anyone who can tell me who I’m paraphrasing, and about what…)

From the cited article:

“Veterans of Ringgold remember using their Fletcher-class destroyer’s five 5-inch batteries”

Yeah, that’s a mighty one (1) barrel per battery. Pretty brave and aggressive, gentlemen!

OMG. Last line of the cited article: “She [Ringgold] served in the fleet until 1987.”

Whoa.

Talk about “If its stupid but it works, it isn’t stupid!”

See —

…Lt. Wayne A. Parker, Ringgold’s engineering officer, described the ship coming under fire:

“When the enemy found the range,” Parker wrote, “the Ringgold took its first hit. A 5-inch shell struck the starboard superstructure, penetrated through the sick bay and the emergency radio room, and ricocheted out into the 40-millimeter gun sponson amidships. Luckily, the shell didn’t explode, but metal fragments hit one of the torpedomen in the chest, knocking him off the torpedo mount and down onto the gun deck.”

Another Japanese shell, also a dud, struck Ringgold’s hull below the waterline. Flooding began in the aft engine room. Parker sat on the hole that the shell had made in order to slow down the incoming water that was flooding the bilges – using his buttocks to block the torrent and earning a Navy Cross. Parker later directed the installation of a makeshift patch over the hole.

>>It is my understanding that the number one request from troops

>>that made it ashore was radios, radios, radio batteries, and

>>more radios.

RonaldF,

I would appreciate a source/cite for that bit of fact.

>>I am so looking forward to the book you write out of all this.

Kirk,

I’m working that one column at a time.

This column was an exercise in four of the “methodologies” I am developing for the book:

1. The difference military service fighting styles make.

2. The difference available technological tool sets make in the way we today view past events versus the the way people at the time saw things.

3. The need to view past events through original source documents, to include military professional journals like Military Review and period technical procurement and fighting method documents, versus the institutional histories.

4. The need to place events of the past in context with institutional politics of the era.

These methodologies don’t preclude the use of institutional service histories or other secondary sources written from them, in fact the foot notes of the service histories and secondary sources are incredibly useful research tools I apply all the time.

The difference is that I am using my day job skills as a Federal Government Quality Auditor to validate those histories by comparing the various original document points of view of the same events against each other and then following the ripples of those events through military doctrine, procurement and technical fighting documents across the services.

In a sense, I am following a document audit trail and writing a report based on that trail with every column.

The “validation against original documents step” seems to be missing from much of the secondary source histories of the era because so much of the original documentation was classified for so many decades after WW2 ended. The institutional military historians could not write about Ultra code breaking in the 1950’s, for example, and the outside historians could not use what they didn’t know existed.

That is why I throw around terms like “Methodologically Flawed” — academic fighting words — about many recent histories in my columns.

On the radio issue, the novel “Once an Eagle” has a chapter on a practice invasion of Monterrey beach in 1940 by the Army in which the issue of radio failure due to sea water comes up. The author of the book, Anton Myrer, was a Marine in WWII and I wonder if his experiences were a factor in writing that chapter that way. For anyone not familiar wit the novel, it is assigned reading by the Army War College.

Michael Kennedy,

People of that era, just like folks today, write about things that were important to them.

The _WHY_ such things were important to them, in context, is missing from current histories.

“I am so looking forward to the book you write out of all this.”

Me, too.

A neap tide isn’t an ebb tide. The tide oscillates between a High Tide and a Low Tide. A particularly high High Tide is called a Spring Tide, and a particularly low High Tide is a Neap Tide. These phenomena each occur twice a month. Talk of “a once in several decades ebb or “neep tide” that prevented the high tide from rising enough” is rubbish, and if advanced by someone with nautical knowledge is presumably mendacious. At a guess, the attackers hadn’t done their homework on the local tides, or somehow were either too early or too late in their attack; or, just possibly, a storm had attenuated the tidal rise. I say “just possibly” because if a storm had been the problem, the excuse would presumably have been made pretty loudly.

Trent – the comment about radios came from one of Ballantines History of WWII, I think? Lt. Hawkins is said to have made the comment, but I think it was second hand information. I’ll try to dig through my father’s books and see what I can find.

My Dad was in the 7th Infantry during Korea and he tells me that they had no amphibious training. Since he went in 1952, this makes sense.

“At a guess, the attackers hadn’t done their homework on the local tides, or somehow were either too early or too late in their attack; or, just possibly, a storm had attenuated the tidal rise. I say “just possibly” because if a storm had been the problem, the excuse would presumably have been made pretty loudly.”

The timing argument is one I have heard before. You are correct about tides, of course, although a neap high tide is lower than usual. thus the planners needed to be aware of this. If they were counting on a high tide to get the Higgins boats over the reef, it was crucial.

“A tide in which the difference between high and low tide is the least. Neap tides occur twice a month when the Sun and Moon are at right angles to the Earth. When this is the case, their total gravitational pull on the Earth’s water is weakened because it comes from two different directions. ”

There are seasonal very high tides, often related to far offshore storms. Newport Beach, near where I live, gets flooded a couple of times a year by these very high tides.

Dearieme,

Good catch.

There was an _extremely low_ Neap Tide during Tarawa to the point that the high tide never rose. Thus the LCVP’s could not get onto the beach on the lagoon side of Betio during the battle.

The materials I read about it later said that there was a rare lunar conjunction that the planners were unaware of that was responsible.

I have to go find the resource and rewrite that passage.

This passage is on wikipedia:

The Marines started their attack from the lagoon at 09:00, thirty minutes later than expected, but found the tide had still not risen enough to allow their shallow draft Higgins boats to clear the reef. Marine battle planners had not allowed for Betio’s neap tide and expected the normal rising tide to provide a water depth of 5 ft over the reef, allowing their four foot draft Higgins boats room to spare. On this day and the next the ocean experienced a neap tide, and failed to rise. The neap tide phenomenon occurs twice a month when the moon is near its first or last quarter. In a neap tide the countering tug of the sun counteracts the pull of the moon, and water levels deviate less. In this instance the moon was at its farthest distance from the earth and exerted even less than normal gravitational pull, leaving the waters relatively undisturbed. In the words of some observers, “the ocean just sat there,” leaving a mean depth of three feet over the reef.

Ah, this will do:

https://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/EarthSC202Notes/TIDES.HTM

The Battle of Tarawa, November 20, 1943

Near Earth’s perihelion: strong solar tides

Near lunar apogee: weak lunar tides

Near last-quarter moon: neap tide

Overall effect: unusually small tidal range

Tarawa The effect of tides on the Boston Tea Party is a humorous footnote to history. The effect of tides on the battle for Tarawa during World War II was anything but. Tarawa was one of the easternmost Pacific islands held by the Japanese, and the assault was the first amphibious assault in the Pacific during World War II. Sketchy tide data for the island suggested a tidal range of about seven feet. However, there were puzzling rumors of periods when the tides on Tarawa almost ceased, a condition local mariners called a A ‘dodging tide’.

Tarawa is a type example of an atoll, a flat-topped submarine mountain capped by coral. Most atolls, like Tarawa, have a wide shallow lagoon ringed by low coral islands.

The only island of consequence at Tarawa was one with an airfield. The plan was for Allied ships to stand offshore in deep water and send landing craft into the lagoon. The landing craft would go as far in as possible and discharge troops.

The invasion was set for November 20, 1943 when tide conditions were expected to be favorable. At low tide in the early morning, the bombardment would begin. As the tide rose and water levels in the lagoon reached 1.5 meters (five feet), landing craft would head ashore and by noon, at high tide, heavier craft could come ashore bringing tanks and supplies.

This isn’t the sort of thing you can call off and reschedule if things go wrong, as they did. Once an attack is under way, the enemy knows your intentions. Any delay merely gives the enemy time to reinforce or escape.

Tarawa Unfortunately, the rumors of almost-tideless periods at Tarawa were true. November 20 was near last-quarter moon, resulting in a neap tide. Military planners knew about the risks of neap tide but did not realize the moon was unusually far from earth as well, weakening its tidal effects even more. Also, the Earth was only seven weeks from perihelion, meaning solar tides were unusually strong as well.

The top diagram (Trent — see link) shows what planners expected. The bottom one shows what actually happened.

Landing craft hit bottom hundreds of meters offshore and the Marines had to wade ashore under heavy fire. Once ashore, they had to fight without assistance, because supply ships could not come in. For 48 hours, the tidal range was only 60 centimeters (two feet), and it was four days before the tidal range increased to normal. 1027 Marines were killed and 2292 wounded in the battle.

Trent – I had to walk about 1000 yards to Jr. High. After reading a book on Tarawa, it really put things in perspective. How the heck did these guys do it?

Unfortunately, as per your request, I couldn’t find the quote I mentioned, and many of my father’s books were not sourced. I now remember how difficult it was to write a paper with legitimate hard sources. In my internet search, I found that the 8 inch guns on Tarawa were not from Singapore, but from British guns sold to Russia. (I’ve read this mistake in several books and articles).

I did find a site with writings from Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC. The only quote I could find was from Colonel Shoup. He couldn’t land on Betio till noon and sent word via the Primary Control Officer to send “ammunition, water, blood plasma, stretchers, LVT fuel, more radios. It doesn’t help history archives when most of the radio operators and officers are killed – truly brave and heroic men

The sources include –

USMC archives

2d Marine Division Operations Order 14 (250oct43)

2d Amphibious Tractor Battalion combat report – etc. and many others that you almost certainly have read.

I did a paper on the raid of Dieppe in college and see that my sources are all generically terrible. I was in a hurry and did not care much about the project. I now want to revisit the history as it still seems to have so many unanswered questions, and problems that are similar to your current writing. It is unbelievably difficult to find the actual truth.

Good luck to you on your book. I have a new appreciation about the difficulties you face.

Had a neighbor who was a veteran of Tarawa. Asked him how he survived – said he’d take a breath, sink 7-8′ to the bottom walk a bit – pop up – take a breath, go back down. Picture that with all the field gear.

“a rare lunar conjunction that the planners were unaware of that was responsible”: aye, they hadn’t done their homework. The movements of the moon are entirely predictable. The effect of the moon on tides had been known in rough terms since the ancient Greeks; the explanation came with Newton’s Principia, and lots of practical refinements followed.

“There are seasonal very high tides, often related to far offshore storms. Newport Beach, near where I live, gets flooded a couple of times a year by these very high tides.” Where I grew up, on the Solway Firth off the Irish Sea, we would get a bit of flooding with exceptionally high Spring tides: surprise would occur only if there had been a sou’west gale to help them. I once lost some earnings from a schoolboy job at the harbour when a sou’wester meant that the flow tide came up a little sooner than expected and a ship came in early, while I was still cycling to work. It taught me not to trust even the tide tables. But this Pacific disaster would seem to have occurred because they hadn’t even calculated their tide tables properly. Slapdash planning kills people, alas. How shameful.

Dearieme,

Yes they did screw the pooch on their nautical astronomy.

It wasn’t until 1987 that there was a professor from Southwest Texas State University, named Donald Olson, who published an article titled “The Tides at Tarawa” in Sky & Telescope that explained the combination of a strong solar perihelion tide, weak lunar apogean tide plus the usual quadrennial last-quarter moon neap tide could combine for a no-tide period.

The two dates for that ‘no-tide’ period for Tarawa in 1943 were 12 April and 19 November.

There was even a Kiwi Major warning US Navy planners about a”dodging tide” on the date of the landing — he was ignored.

I found the above on a Google book preview of this:

Joseph H. Alexander, “Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa”

Naval Institute Press, c 1995, ISBN: 1-55750-031-2

Page 76 had the Neap tide explanation I dropped above.

In other news about Tarawa:

http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/international/radio/onairhighlights/nz-coastwatcher-bodies-may-have-been-found-on-tarawa

Story I heard was that the US Navy ignored the advice of the coast watchers

There was a slight update to the column text to reflect the Neap tide information I found due to comments.

“There was even a Kiwi Major warning US Navy planners about a”dodging tide” on the date of the landing ”” he was ignored.”

I had considered asking whether the US had sought info from the RN, RAN, and RNZN, but thought better of it; it might have seemed as if I was rubbing it in a bit. Planning blunders happen all over the place; the art, I suppose, is to pin down what is knowable – such as tides – and then do the best you can with what is uncertain. Mind you, if a Kiwi soldier – as distinct from sailor – knew better ”¦..

Here is a bit more detail of USMC radios at Tarawa.

Even by the US Army standards of December 1943, this was a laughably low level of radio equipment…and none were with the LVTs.

http://www.tarawaontheweb.org/usmcradio.htm

USMC Communications Equipment

.

Concerning Marine radios — At the battalion level, up through Saipan, we had no hand held radios. The TBY, a one man back pack, battery operated unit was used at the company level. It was fairly efficient, but usually confined to line of sight operation. Going into Saipan there were 6 TBY’s in service. At the battalion headquarters level we had one TBX powered by a generater. It usually was carried by 4 men and consisted of antennea, generater, transmitter, and reciever. Efficient, but the antennea had a tendency to be seen from a distance, and getting 4 men together after the Tarawa landing proved to be impossible. We had a TCS radio in our communication jeep, and it was great, but it didn’t get ashore on Tarawa, and got ashore too soon on Saipan.

“Where do they find these kind of men?”

I think that was from the film ” The Bridges of Toko-ri.”

Renminbi,

Bingo! Thanks…

Reportedly, Eddie Albert, (Edward Heimberger LT j.g., USNR), sailed to Tarawa as a salvage officer aboard one of the troop ships, USS Sheridan. During the battle, he was in charge of one of the small salvage boats launched by the transport. When it became apparent that the Marines were having trouble getting ashore due to the tides and fire from the Japanese, Albert took his boat toward the beach, picking up Marines out of the water. He did this at least four times, in addition to taking supplies ashore and picking up wounded Marines to return to the larger ships offshore. After the battle was over, he recovered the bodies of marines from the water near the beach. More than forty years after Tarawa, Albert was awarded the Bronze Star with Combat V for his actions during the battle.

http://www.militaryphotos.net/forums/showthread.php?124049-Eddie-Albert-From-Tarawa-to-quot-Green-Acres-quot-MC-Times

This is off topic a bit here Trent but I ran into a car club member today whose father – who died last year – would have been fascinating to talk with. Worked on the Manhattan Project – even up until his death most of what he did was still classified – but he went to Tinian to help arm the bombs.

Said that during the arming of Fat Man (a multi stage process) someone tripped over a cable (or something similar) and the thing nearly went off – they had to open and access plate or something and disconnect something in a hurry.

He worked at Sandia Labs –