Air space control was one of the themes of my previous, April 4, 2014, column “Unit Conversion Error in the Pacific War” when it looked at the issues of coordination between military services over how to use Radar in terms of units of distance and grid type versus polar type reporting of Radar position data in order to control air space around air fields and naval task forces.

Expanding on that theme, today’s column is one about a forgotten lesson of World War 2 (WW2) global warfare from the South West Pacific Area in 1943 that was repeated by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the “Operation Allied Force” Air War over Kosovo in 1999. How it happened requires returning to a theme from my previous Pacific War history columns, namely, that you don’t know a thing about how a military theater in WW2 fought without knowing how they used their Radars. That’s because changing electronic technology in the form of Radar revolutionized things like airspace control, gunnery and weather forecasting simultaneously in the middle of a World War, and its deployment and use were very uneven between military services and allies based on that theater’s overall priority. Something very similar happened in 1999 with the uneven deployment of digital technologies between American military flying services and those of its European NATO allies.

In WW2, issues arising from those Radar based changes often wound up affecting decisions at the strategic and political policy levels of military theaters, hidden unnoticed for decades under layers of classification and post-war institutional reputation polishing. The role of air space control in the South West Pacific Theater’s June 1943 Operation Chronicle was a perfect example of this. Specifically how units of the same military service — US Army Air Force in the form of General MacArthur’s 5th Air Force and Admiral Halsey’s 13th Air Force — in two adjacent military theaters differed so greatly in how they controlled their air space they couldn’t talk to one another. These “hidden from history by post-war institutional agenda” differences in 1943 Global Coalition War reemerged in NATO’s 1999 Kosovo War Air Campaign with a vengeance.

SETTING THE STAGE

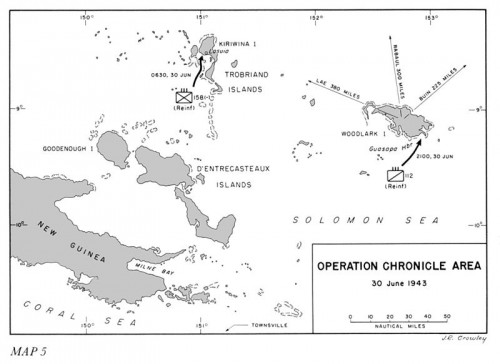

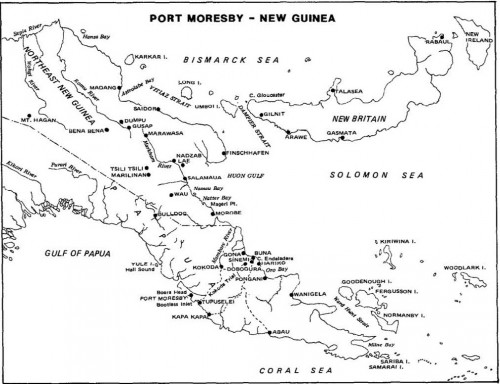

The figure below is from the foremost institutional history on Operation Chronicle, John Miller’s “Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul” from the US Army in WWII “Green Book” Histories.

When you visit Miller’s Green Book history, the US Air Force institutional history “The Army Air Force in WWII IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan August 1942 to July 1944”, Volume VI from Adm. Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of US Naval Operations in World War II series “Breaking the Bismarks Barrier 22 July 1942 – 1 May 1944,” as well as the US Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) Report No. 71 “The Fifth Air Force in THE War Against Japan” you will not find that not much is said of the invasions of Kiriwina and Woodlark islands in June 1943, other than they were done to,

1) Establish airfields closer to Rabaul and

2) The amphibious operations were “Learning experiences” AKA fiascoes of poor preparation and execution.

Wikipedia’s entries on the subject of Operation Chronicle are a little better than those institutional histories regards adding some context to the radar issues involved, mentioning the extension of radar coverage on Kiriwina by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) prior to the operation. Kiriwina Airfield was operational 18 August 1943 with the Spitfire equipped No. 79 Squadron RAAF 18 August 1943 and was later joined by the P-40 Kittyhawk equipped No.76 Squadron RAAF, a veteran of the Battle of Milne Bay, and the rest of No. 73 Wing in September 1943.

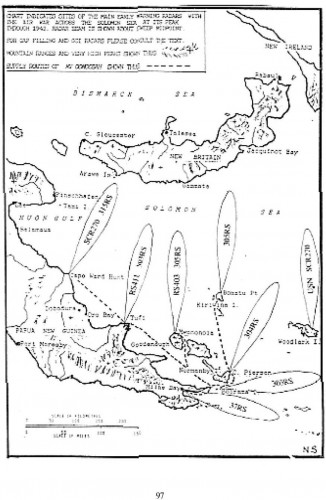

You have to go to a institutional narrative shattering book this column has referenced a number of times before, Ed Simmonds and Norm Smith’s, “ECHOES OVER THE PACIFIC: An overview of Allied Air Warning Radar in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines Campaign” to understand the really understand role of Operation Chronicle had in extending of the Allied Radar network to cover the aerial north eastern flank of General MacAthur’s sea lines of communications. (See Radar coverage map below)

And also see how badly that plan went wrong, as executed, for reasons of convoluted chains of command and differing rates of technological weapons deployment. Problems all to familiar to NATO pilots of Operation Allied Force, the 1999 war between Serbia and NATO in the skies over Kosovo.

This excerpt from page 193 details how half that planned radar network extension failed when Admiral Halsey’s 13th Army Air Force, US Marine and US Navy ARGUS radar teams, forming the “15th Fighter Sector” in the SWPA could not speak to the Fifth Army Air Force’s Australian crewed 16th Fighter Sector on Kiriwina, nor either of the joint US-Australian 9th fighter Sector at Milne Bay and 4th Fighter Sector at Port Moresby.

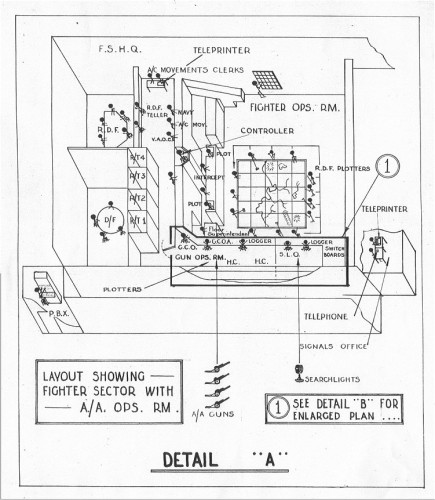

A comprehensive defence organization was soon established on Woodlark operated by the US Navy ARGUS 1 under the control of the 6th Army, the Naval Base on the island and Vth Fighter Command. Two SCR270s, one SCR602 and an SCR268 anti-aircraft radar fed information to the plotting board in a Combat Information Centre.

.

This centre was probably the most comfortable and best protected fighter control centre in the SWPA. It was a two-story air-conditioned building sunk into a hole in the coral. Shipping movements in the area were monitored as were the movements of the PT rescue craft.

.

When no information from this centre was being received by the Fifth Air Force plotting boards a visit by Capt. Wilde in July 1943 established the reasons why. The limited staff available had difficulty in handling the increasing volume of information coming to hand. Again the procedure being used differed from that of the Fifth Air Force and to complicate matters the plotting grids used on the maps differed. For these reasons full cooperation between the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces did not eventuate.

The sea line of communication guarded by these radars were critical to covering Operation Postern, the September 1943 Amphibious invasion of Lae by the Australian Army and aerial invasion of Nadzab by the US Army’s 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment in what USAAF histories call the Huon Peninsula Campaign and Wikipedia refers to as the Salamaua-Lae campaign.

While US Navy radars planted, and the air strip created on, Woodlark may have been as Adm Morison describes ‘an investment that did provide a good return.’ This was not true for Kiriwina as page 140 of ECHOS OVER THE PACIFIC explains in terms of radar’s support role and the logistical support for P-38 fighter escorts in General Kenney’s largest air raids on Rabaul:

On 12 October the Allies mustered more than 300 aircraft including Liberators, Fortresses and fighters to attack the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul. A similar devastating blow was delivered on 29 October. In between these major attacks Mitchells and Beauforts continually attacked Japanese bases and Beaufighters (Whispering Death) attacked supply vessels and troop concentrations. For the attacks on Rabaul, Kiriwina was the rendezvous of the Allied air armadas and refuelling point for the long range Lightning fighter escort.

.

Consequently 305RS (Radar station 305) plotted aircraft continuously and reported ranges sometimes in excess of 200 miles. The high flying Lightnings gave these distant echoes. An important function during these raids was to pinpoint where any returning damaged aircraft was ‘ditched’ so that crew rescue procedures were carried out immediately. All the information was, of course, disseminated from No. 114 MFCU. (Australian Mobile Fighter Control Unit).

FACTIONAL FIGHTER SECTORS EXPLAINED

What “Fighter Sectors” are and how different US Army Air Forces in the Pacific wound up unable to communicate with one another requires a little explaining.

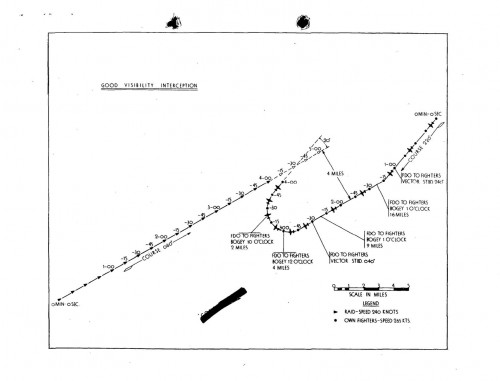

To begin with, “Fighter Sectors” were command and control organizations invented by the British as a part of their “Chain Home” air defense system. They are responsible for the control and defense of air space over a defined geographic area. Fighter sectors take data from multiple sources including radar, ground observers and signals intelligence (both direction finding and code-breaking), and then “filters” it for useful information. This filtered information is presented in the form of “plots” of enemy and friendly aircraft on an “operations board” so that the senior fighter controller can direct defending fighters, search lights, smoke generators and anti-aircraft guns to destroy the most enemy, limit the damage caused by enemy attacks, and prevent defending fighters and antiaircraft defenses from having “friendly-fire” incidences.

The point of fighter direction from a Fighter Sector in daytime was to place defending fighters on a converging course with enemy aircraft at a higher altitude with the sun behind them. This left defending fighters get a surprise “bounce” — an aerial ambush — on an attacking aircraft formation to inflict unanswered casualties and hopefully break up attacking formation integrity. Thus preventing an unanswered coordinated attack on whatever enemy bombers and fighters were aiming to destroy. This was especially critical in protecting Allied carriers from a coordinated dive bomber/torpedo plane attacks that the Japanese in the Pacific, and the Germans in the Mediterranean, delivered in 1942-1943.

These Fighter Sector organizations changed in scope and capability as the British developed improved technology in the form of more and better height finding radars, radio homing beacons for landing in bad weather starting in 1941, longer ranged VHF band radios to replace shorter ranged “MF” and “HF” band aircraft voice radios starting in 1942 and finally the “Mark III” identification friend or foe transponders in 1942 to separate the “Bogies” (unidentified planes) from the “Bandits” (enemy planes).

The instructors for the US Navy, USMC and both the 5th & 13th US Army Air Force radar operators/fighter controllers in Operation Chronicle learned how to do their job from the Royal Air Force in Canada in the Fall of 1941 The first 66 students of “No. 31 Radio School, Royal Air Force” — located at Clinton, Ontario, about 50 miles north of London, Ontario and opened on 20 July, 1941 were Americans. Twenty-five were US Navy officers and 36 were US Army men and they constituted its first class. They were joined in September 1941 by students of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

This was in the short time period after the British “Tizard Mission” to the USA that exchanged American and British Radar and code-breaking secrets and before Pearl Harbor. Due to the US Neutrality Act it was, strictly speaking, illegal. And more importantly, none of the students these instructors later trained were available to American forces in the Pacific until six months after the Japanese struck on December 7th 1941.

This goes a long way to explaining why the Fifth Air Force, created on 9 August 1942 by order of American Army Chief of Staff, General Marshall, and established in Australia on 3 September 1942 under the command of Major General George Kenney, had such a divergent Fighter Sector fighting culture.

At the time of the Fifth Air Force’s creation, Australian and American air forces had been fighting two months long, and losing, campaigns over Northern Australia and Southern New Guinea beginning in February 1942. And in those hard months, in the skies over Darwin, Australian Northern Territories, Port Moresby and Milnie Bay New Guinea, and from North Africa of all places, a Fighter Sector fighting culture with Australian-American “accent” was born.

FROM THE FLAMES OF AUSTRALIA’s PEARL HARBOR

On 19 February 1942, to cover the 20 February landings on Timor, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 1st Carrier fleet struck Darwin with 188 aircraft, followed by a further 54 land based bombers. This air strike flattened the airfields around Darwin and ravaged the naval and merchant shipping in its harbor. Some 30 aircraft were destroyed including 10 American P-40’s designated as reinforcements for Allied forces on Java in the Dutch East Indies modern day Indonesia as well as sinking 8 ships, causing three more to ground themselves while dodging attacks and damaging another 25 vessels.

General MacArthur was nearly killed on a B-17 in his epic journey from the Philippines to Australia, as it had to divert from a Darwin airfield to another air field 50 miles away from the city, in order to avoid a Japanese air raid in March 1942.

In the months that followed the first “Fighter Sector” to see combat in Australia — No. 5 Fighter Sector with the first six Australian built light weight/air warning (LW/AW) radar prototypes — was established at Darwin. It’s first fighter compliment, from March through August 1942, was from the 49th Pursuit Group, USAAF, commanded by then Lt. Col Paul B Wurtsmith. The 49th had three fighter squadrons with P-40E fighters and the 49th Interceptor (later Fighter) Control Squadron to provide fighter direction command and control. The 49th Group faced 27 air raids in that time, lost 17 P-40’s in combat (six pilots safe) with an additional 22 damaged and 28 destroyed due to non-combat conditions. It claimed a total of 63 Japanese planes destroyed in return for these efforts.

It was replaced at Darwin by the RAAF Spitfire V equipped No. 1 Wing which was equipped initially with three, then four, fighter squadrons. (The three squadron USAAF “Group” was the same size as the standard RAAF “Wing.”) No.1 Wing had a few veterans of North African fighting and many green pilots, most of whom were filled with RAF Spitfire snobbery regards its turning maneuverability and dog-fighting ability. The problem for the No. 1 Wing was the Japanese Navy’s Mitsubishi A6M Zero, AKA Zeke, and Japanese Army’s Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa, AKA Oscar, were better in exactly those characteristics and had an acceleration advantage over the Spitfire below 20,000 feet (6100 meters). No. 1 Wing also suffered from drop tank shortages that limited range, De Havilland constant speed propeller mechanism malfunctions over 20,000 feet, spares shortages, plus tropical air filter and, finally, a set of cannon armament defects with their Spitfire V’s not cured until December 1943.

Despite American and RAAF P-40 pilots warning them, No. 1 Wing didn’t shed their illusions of Spitfire’s superiority until after many stinging losses to the Japanese and the hot and dusty Northern Australian climate. By the time the Japanese finally gave up on attacking Darwin, No. 1 wing lost 33 Spitfires in combat with an additional 46 damaged and 31 destroyed due to non-combat conditions, while claiming a total of 69 Japanese aircraft destroyed.

In addition to its Spitfires, the No. 1 Wing also brought with it one other RAF Desert Air Force legacy… Air Marshall’ Arthur Tedder’s 1941 fighter control doctrine. As USAF historian John F. Kreis, laid out in this 1988 study “Air Warfare and Air Base Air Defense 1914-1973”:

The fighter control that developed was not a true ground controlled intercept system such as used over Britain; the controllers did not work directly with radar scopes. Rather, they used a variety of data passed to them to maneuver their airborne fighters. Moreover, a GCI system would not have worked because most of the RAF’s aircraft had high frequency radios with a range of fifty miles. It was not until 1942 that the RAF began to change to VHF radios in Africa, giving them an extended range of one hundred miles or greater.

When General Kenney took over as Allied Air Force and Fifth Air Force commander in late 1942, he promoted Paul B Wurtsmith to one star general in charge of the Fifth Fighter Command. Wurthsmith’s primary duties included establishing and coordinating Fighter Sectors using any radar available — American or Australian — plus three USAAF Fighter Control Squadrons from the 49th Group and two other American fighter groups in tended to reinforce the Philippines, to guard MacArthur’s sea lines of communication to Australia’s Queensland, then from there across the Coral Sea to Port Morseby, New Guinea, then finally around Milne Bay through the Ward Hunt strait into the Solomon Sea. (See the PORT MORESBY NEW GUINEA map below) He was limited by shipping and supply priorities to using the long range “HF” band radio telegraph equipment that Australian industry could provide Australian-American Fighter Sectors. Thus his Fifth Fighter Command Signals section had to integrate arriving American radar units of the 565th Signal Air Warning Battalion into the existing Australian Fighter Sector system, rather than impose the “Standard Model” RAF-instructor-in-Canada taught Fighter Sector. A Standard Fighter Sector that by 1943 relied upon improved RAF invented VHF radio and supporting electronics that MacArthur’s Theater lacked, and Admiral Halsey’s South Pacific Theater had in relative abundance.

At the time of Operation Chronicle in June 1943, land based airpower in the South Pacific Theater had just moved to the 1942 RAF state of the art Fighter Sector technology & doctrine with 100 mile range VHF radios and Type III identification friend or foe aircraft transponders, while MacArthur’s South West Pacific Theater had not. More importantly, Kenney as commanding general of Allied Air Forces couldn’t move to that state of the art without enough equipment to transition both the Fifth Air Force’s 1st Air Task Force and No. 9 Operational Group of the RAAF simultaneously…while in combat.

That just wasn’t going to happen. It was far more important that SWPA air forces keep acting in a unified, cohesive and coordinated manner, even at a lower level of technology, than it was to have the latest and greatest technology.

This was the lesson learned, buried and forgotten…only to be learned again 56 years later.

Repeating WW2 SWPA History in OPERATION ALLIED FORCE

In 1999 President Clinton’s American lead NATO coalition forced President Slobodan MiloÅ¡ević’s Serbia to abandon its Kosovo province to the Muslim majority there after another round of Serbian ethnic cleansing began the final War of Yugoslav Succession. The predominant fighting in this war was an air campaign called Operation Allied Force. The three legs of the airpower stool for Operation Allied Force were American B-2 Strategic bombers carrying an early version of the GPS guided bomb and B-52 delivered cruise missiles, American ships with cruise missiles and carrier aircraft equipped with laser guided bombs supported by EA-6B jamming planes and finally US-NATO land based airpower, predominantly NATO standard F-16 fighters, from Aviano Air Base in Italy.

In the years since WW2, the VHF band and most of the UHF radio bands had been reserved for commercial television with a small fraction of the UHF band at the 225-400 MHz frequency band being reserved for US-NATO standard military radio traffic. This band proved to be easy to monitor and easy to jam. The USA developed both the “Have Quick” frequency hopping radios and the Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) data links to move information between pilots and air defenses around that weakness.

This is how Wikipedia describes JTIDS:

The Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) is an L band TDMA network radio system used by the United States armed forces and their allies to support data communications needs, principally in the air and missile defense community. It provides high-jam-resistance, high-speed, crypto-secure computer-to-computer connectivity in support of every type of military platform from Air Force fighters to Navy submarines.

JTIDS effectively provided secure, wireless, digital internet to American airpower. The problem was that in 1999 that the European NATO powers, outside of a small portion of the RAF patrolling the Iraqi “No-Fly Zone” with the USAF, lacked this equipment. American airpower in Italy was very much in the same boat as Fifth Air Force’s 1st Air Task Force and No. 9 Operational Group of the RAAF circa June 1943 in New Guinea. US-NATO combined strike packages had to operate without JTIDS and HAVE QUICK to launch coordinated attacks in exactly the way Kenney’s allied air forces operated without VHF radio. There was no other choice.

How much the Serbian air defenses relied upon intercepted NATO pilot UHF voice communications is still not clear in 2014. The resilience and protracted survival of Serbian air defenses as a “Force in being” in 1999, compared to the rapid extermination of Iraqi Air Defenses in 1991’s Desert Storm, heavily implicates this NATO equipment deficiency. The following is from the RAND Corporation’s report “NATO’s Air War for Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment” —

In addition, many NATO European fighters lacked Have Quicktype frequency-hopping UHF radios and KY-58like radios allowing encrypted communications. As a result, U.S. command and control aircraft were often forced to make transmissions in the clear to those fighters about targets and aircraft positions, enabling the enemy to listen in and gain valuable tactical intelligence.

The continued existence of Serbian air defenses forced NATO aircraft to high altitudes, where Serbian Army shoot and scoot tactics and the poor decoy recognition capability of Allied pilots and unmanned air vehicles over Kosovo extended the campaign far past the intended one to two weeks. The 78-day campaign stretched the NATO coalition to near political breaking point over American B-2 GPS bomb strikes against President Slobodan MiloÅ¡ević’s regime security forces, transportation and power targets in Serbia. It was finally that B-2 Stealth bomber plus GPS bomb threat to President Slobodan MiloÅ¡ević’s regime security vital interests that forced Serbia to abandoned Kosovo.

NATO learned its lesson from Kosovo and as of 2007 all American and NATO air forces possess HAVE QUICK and JTIDS…while America is starting to move on to a new generation of digital frequency hopping internet radios. Hopefully these new US digital radios will be designed to be “backwards compatible.”

Thus ends the story of a WW2 South West Pacific theater lesson of global coalition warfare learned and forgotten…perhaps to be forgotten again?.

Sources and Notes:

W.F. Craven & J.L. Crates, The Army Air Force in WWII — IV The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan August 1942 to July 1944, pages 164-165, on-line at http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/IV/AAF-IV-6.html

Anthony Cooper, “1 Fighter Wing’s Spitfire VC cannon scandal” — http://www.darwinspitfires.com/articles/the-spitfire-vc-s-faulty-armament.html

Anthony Cooper, “Shortages of drop tanks, spares and Spitfires” == http://www.darwinspitfires.com/articles/shortages-of-drop-tanks-spares-and-spitfires.html

Anthony Cooper, “The Vokes air filter controversy” http://www.darwinspitfires.com/articles/the-vokes-air-filter-controversy.html

“5TH AIR FORCE USAAF IN AUSTRALIA 1942 1945” — http://www.ozatwar.com/5thaf.htm

“565th Signal Air Warning Battalion” – Australia @ War — www.ozatwar.com/usarmy/565thsignalbattalion.htm

49TH FIGHTER GROUP (FORMERLY THE 49TH PURSUIT GROUP) IN AUSTRALIA DURING WW2 http://www.ozatwar.com/49fg.htm

Theodore F. Karpel, 1stLT, Signal Corps, “History of US Aircraft Warning System in SWPA” unpublished manuscript dated September 1944, Signal Office, Fifth Fighter Command, Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) archives. Pages 21 24

John F. Kreis, “Air Warfare and Air Base Air Defense 1914-1973,” Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Sashinton. D. C. 1988 pages 137 – 173 and 217 – 257

Benjamin S. Lambeth, “NATO’s Air War for Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment” Rand Corporation, RAND’s Project AIR FORCE. Document No. MR-1365-AF, C 2001, ISBN/EAN: 0-8330-3050-7 pages 167-168 — http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1365.html

In addition, many NATO European fighters lacked Have Quicktype frequency-hopping UHF radios and KY-58like radios allowing encrypted communications. As a result, U.S. command and control aircraft were often forced to make transmissions in the clear to those fighters about targets and aircraft positions, enabling the enemy to listen in and gain valuable tactical intelligence.147

.

147 Since allied aircraft could not receive Have Quick radio transmissions and since enemy forces made no effort to jam allied UHF communications, which Have Quick was expressly developed to counter, the Have Quick capability was not used by U.S. combat aircrews during Allied Force.

.

and

.

For their part, U.S. aircraft equipped with JTIDS frequently were not allowed to rely on that asset, but were instead obliged to use voice communications to ensure adequate situation awareness for all players, notably allied participants not equipped to receive JTIDS signals.149

.

149 David A. Fulghum and Robert Wall, “Data Link, EW Problems Pinpointed by Pentagon,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, September 6, 1999, pp. 8788. The JTIDS offers aircrews a planform view of their tactical situation, as well as a capability for real-time exchange of digital information between aircraft on relative positions, weapons availability, and fuel states, among other things. It further shows the position of all aircraft in a formation, as well as the location of enemy aircraft and ground threats. Fighters can receive this information passively, without highlighting them selves through radio voice communications. See William B. Scott, “JTIDS Provides F-15Cs ‘God’s Eye View,’” Aviation Week and Space Technology, April 29, 1996, p. 63.

John Miller, US Army in WWII, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabul, pages 49 57 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Rabaul/USA-P-Rabaul-5.html

OPERATION ALLIED FORCE — http://www.afhso.af.mil/topics/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=18652

The RAF Fighter Control System — http://www.raf.mod.uk/history/fightercontrolsystem.cfm

Ed Simmonds and Norm Smith, ECHOES OVER THE PACIFIC: An overview of Allied Air Warning Radar in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines Campaign, Radar Returns 39 Crisp Street Hampton Vic 3188 Australia, Internet Edition – November 2007 ISBN 0 646 24323 3

UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY, The Fifth Air Force in THE War Against Japan, Military Analysis Division, June 1947, pages 87 – 91

WARTIME TRAINING of RCAF RADAR TECHNICIANS IN CANADA — http://www.rquirk.com/cdnradar/cor/chapter3.pdf

R S WOOLRICH, “FIGHTER-DIRECTION MATERIEL AND TECHNIQUE, 1939-45″,” Navigating and Direction Officers’ Association (Royal Navy) — www.ndassoc.net/docs/nd-assoc-fighter-direction.pdf

Wikipedia links

AN/ARC-164 HAVE QUICK II — https://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/ac/equip/an-arc-164.htm

Arthur Tedder, 1st Baron Tedder — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Tedder,_1st_Baron_Tedder

William Jason Maxwell Borthwick — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Jason_Maxwell_Borthwick

HAVE QUICK — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HAVE_QUICK

Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint_Tactical_Information_Distribution_System#Overview

Bombing of Darwin — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombing_of_Darwin

Operation Chronicle — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Chronicle#Base_Development

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1999_NATO_bombing_of_Yugoslavia

67th Fighter Squadron USAAF (P-40) — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/67th_Fighter_Squadron

No. 73 Wing RAAF — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No._73_Wing_RAAF

No. 76 Squadron RAAF (P-40) — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No._76_Squadron_RAAF

No. 79 Squadron RAAF (Spitfire) — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No._79_Squadron_RAAF

Salamaua-Lae Campaign — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salamaua-Lae_campaign

I seem to recall an incident in Afghanistan, before we had major troop involvement. It was just a handful of troops with magic rangefinder binoculars and B-52s with JDAMs. Just found a link: http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/news/653846/posts

Navy used degrees:minutes:seconds.decimal seconds.

Air force used degrees.decimal degrees.

Called in the strike to F/A 18s, did another reading for the Air Force, and the battery died just after the reading, before they read it to the bomber. Changed batteries, and the machine reported its own location on powerup, they dutifully read that to the B-52 crew, who dropped the bomb where they were told.

– Mike

>Face Palm<

Color me unsurprised that the USAF and USN found a way to look at the world through different cartographic lenses.

I’ve been reading about the raid on Dieppe by Canadian forces and find the overt hostility between the various branches of the military to be extreme to say the least. A whole division was wiped out, yet this experience only resulted in a big “I told you so” remark from the other services. Britain obviously had the head start on radar yet both they, and we, had a hard time convincing commanders of its awesome power in both offense and defense. I will take into consideration the giant expansion of our armed forces and the cutting edge technology of radar to those who were given crash courses in its use; however, the Germans faced the same problems and decimated our forces. The Kammhuber line made the most out of what was available. Every time I see Lord Mountbatten, in an old interview, talking about how Normandy would not be possible without the lessons of Dieppe I have to wonder what he means. Ironically, I think we did bring back some German radar equipment. It wouldn’t surprise me if the info was held back from other services – just out of protocol.

RolandF,

The problem we face as readers of WW2 histories is that 99% of the historians address the subject in sweeping descriptions of the main talking points.

As I have tried to demonstrate, that makes for poor histories.

Take for example the Radar lessons applied to the Normandy Invasion.

The Radar lessons from Anzio, the wider Mediterranean back to 1941 and even New Guinea in 1942-1943 all played a part in the invasion at Normandy. This is one of those things that are glossed over in the “main talking points.”

You can see the radar/fighter direction lessons of the American fighter campaign in March thru July 1942 at Darwin Australia, and New Guinea thru early 1943, with 1.5 meter height finding radars that showed up in North Africa right through to Anzio.

Then the triple shock of German radio guided missiles, active radar jamming and Window (AKA early Chaff) kicking the Allies to centimeter wave radar plus VHF fighter radio based fighter direction in early 1944 right in time for Normandy landing in June 1944.

Had the Germans waited six months between Operation Shingle/Anzio (January 22, 1944) and Normandy (June1944) to hit the Allies with that guided missile plus electronic warfare surprise, Normandy would have been a great deal more bloody, costly and protracted.

The only book that got near that flow of radar doctrine was “OVERLORD: General Pete Quesada and the Triumph of Tactical Air Power in WW2” by Thomas Alexander Hughes. And it completely missed the connection between North Australia and North Africa.

As far as the Radar lessons of Dieppe, they showed up in the Allied invasion of Sicily, codenamed Operation Husky. The British put together “Fighter director ships” on landing ship tank hulls with height finding radars and on-ship VHF command and control facilities to make use of them.

These Royal Navy “FD Ships” were later used during amphibious invasions at Salerno, Anzio, Normandy, and the invasion of Southern France. The concept was later copied by the US Navy in the form of microwave radar fighter direction functions on its Amphibious Command ships in its Central Pacific drive starting on or immediately after the invasions of the Guam, Tinian and Saipan.

The radar communication network of which you speak did a good job at Salerno, yet AA fire during Sicily wiped out a large chunk of paratroopers. I always chalked this up to green troops.

If we are going to “Pivot” to the Pacific, we had better spend a lot of time training there. It will take many practices to coordinate the various systems.

>>yet AA fire during Sicily wiped out a large chunk of paratroopers.

>>I always chalked this up to green troops.

More like US Navy naval gunners on amphibious ships and both USN and RN Naval gunners detachments on merchant ships.

There was no in-mission radio coordination between the USAAF Troop Command and the invasion fleet during Operation Husky as of the routing of the paratroop laiden transports.

This was not an issue during the Normandy invasion. They had better radar control, better radios, and they knew enough to route the troop carriers _away from_ the fleet.

In fact, the only Allied aircraft over the Normandy Invasion Fleet in the Channel were American P-38 Lightning’s, as nothing the Germans had looked like them.

Problems with US Navy gunners was still there at Okinawa and it killed a number of US Marine Corsairs in the landing pattern over Yotan air field as it was in 40mm cannon range of the US Navy amphibious shipping off Hagushi beach.