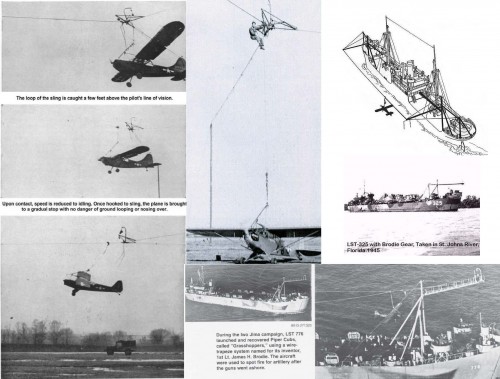

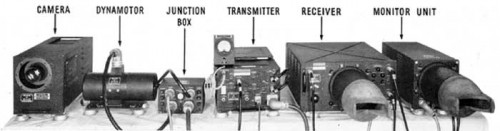

When I started writing my “History Friday” columns, one of my objectives was to explore the “military historical narratives” around General Douglas MacArthur, so I could write with a better understanding about the “cancelled by atomic bomb” November 1945 invasion of Japan. Today’s column is focusing on an almost unknown series of Documents called “The Reports of the Pacific Warfare Board,” and in specific reports No. 31 and 50. This professional lack of interest by the academic history community in these reports represents a huge methodological flaw in the current “narratives” about the end of World War 2 in the Pacific. These two reports amplify and expand an earlier column of mine hitting that “flawed narrative” point titled History Friday: Operation Olympic Something Forgotten & Something Familiar. A column that was about a WW2 “manned UAV” (unmanned air vehicle AKA a drone), an L-5 artillery spotter plane with an early vacuum tube technology broadcast TV camera, pictured below.

These Pacific Warfare Board (PWB) reports have been classified for decades and unlike their more well know, examined by many researchers, and posted on-line European Theater equivalents. Almost nothing from them has made it to the public since their mass declassification in the 1990’s. There are good reasons for that. The National Archive has a 98,000 file, 80 GB finding aide. One that isn’t on-line. Until recently, the only way you can get at archive files like the Pacific Warfare Board Reports is to learn that finding aide and make your own copies using National Archive equipment. This was usually time consuming and cost prohibitive to all but the most determined researchers or hired archivists.

Thanks to the cratering costs USB flash drives and increasing quality of digital cameras built into even moderately priced cell phones over the last few years, this is no longer true. And as a result, the academic history profession is about to have its key institutional research advantage outsourced to hobbyists and bloggers.

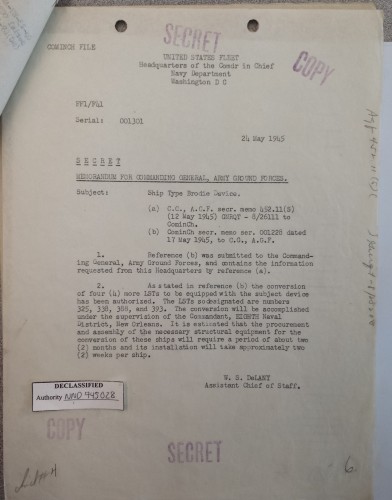

The following National Archives PWB documents were sent to me by ALTERNATEWARS.COM guru Ryan Crierie, first from PWB Report No. 31 BRODIE DEVICES AND INSTRUCTION TEAMS

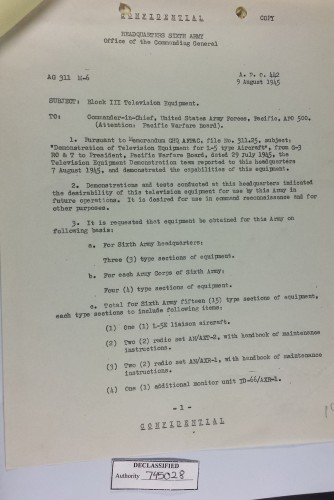

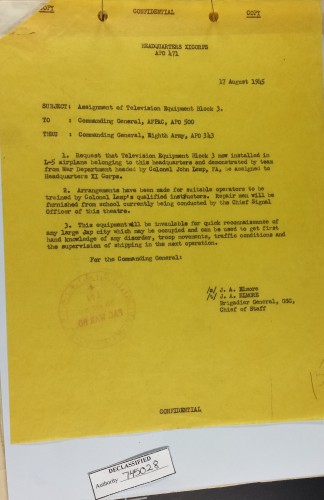

And this extract from the very bureaucratically titled PWB Report No. 50 TELEVISION EQUIPMENT FOR L-5 TYPE AIRCRAFT, DEMONSTRATION TEAM OF BLOCK III EQUIPMENT DEMONSTRATION TEAM.

Thus far we have seen yet another series of reports that adds more detail in terms of military equipment names but essentially repeats what my previous article pulled from the 6th Army’s Field Order 74 and the 1946 US Army Infantry Branch Conference…except for the following

So, not only did the Block III Broadcast TV L-5 spotter plane get demonstrated in the Pacific, one of them was _DEPLOYED_ TO Japan with XI Corps as a part of the Operation BLACKLIST occupation!

This brings up a very interesting question about the Korean War. Given how welcomed and enthusiastically endorsed this capability was by MacArthur’s headquarters, why weren’t there any Block III L-5 “Manned UAV’s” available to General Douglas MacArthur for the Korean War? In particular, why weren’t there any searching for the Chinese troops of the People’s Liberation Army in the hills of North Korea?

I could spend many paragraphs quoting various post-war documents, but the short answer is enough. The Truman Administration created the Defense Department out of the merged Departments of War and Navy, while founding a separate US Air Force and radically cutting the military budget. That left no money and huge turf issues between the US Army and new US Air Force that killed the block III broadcast TV plus L-5 spotter plane “Manned UAV” in the cradle.

Only decades later in the aftermath of the Iraq and Afghan Wars — over the USAF’s bureaucratically killed and buried body — has the US Army gotten the surveillance capability promised to General MacArthur in the fall of 1945.

And now you know another reason why I think the current academic narratives about the end of World War 2 in the Pacific are not only “methodologically flawed,” they may have been made technologically obsolete.

I want to thank you again Trent for doing all of this work your blog posts (I would likely consider them more formal research) are fantastic.

It is amazing how flimsy the common wisdom is when you start to take it all apart.

Large government bureaucracies are much like the nation-states that found them. They have long term interests rather than enemies.

Understanding those interests, their clash over time with the competing interests of other government bureaucracies, and it will lead you to some very interesting and unexamined history.

Hadn’t the Germans fielded an operational smart bomb earlier in the war? I think they hit a US ammunition ship in Italy with it, if memory serves.

They also sank the Italian battleship Roma with one as it saile dout to surrender after Italy surrendered.

The weapon that sank the Roma was the Fritz-X, a armor piercing bomb with radio data link manual command to line of sight system (MCLOS for the military acronym savvy) guidance.

It was part of a pair of such weapons, the other being a glide bomb called the Hs 293, deployed by the Luftwaffe in late 1942

The somewhat similar USAAF VB-1 Azon had a 12% accuracy rate in combat in 1944-45. Both the Hs 293 and Fritz-X were doing somewhat better early on, but that was based upon surprise.

There were six guided weapon bomber squadrons in KG40 and KG100 using the Hs 293 and Fritz-X respectively.

The numbers of Hs 293 and Fritz-X used in combat would have been “several hundred” with far more Hs 293 than Fritz-X having been used. The Fritz-X proved to make the carrier planes more vulnerable than the Hs 293 — it had to climb and slow down to keep the bomb in the bombardier’s site — so by the time of the Normandy invasion KG100 was using the Hs 293 as well.

Wikipedia has a couple of good articles on both radio guided weapons, which I clipped from below —

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_X

The only Luftwaffe unit to deploy the Fritz-X was Gruppe III of

Kampfgeschwader 100 Wiking (Viking), designated III./KG 100, the

bomber wing itself evolved as the larger-sized descendent of the

earlier Kampfgruppe 100 unit in mid-December of 1941. This unit

employed the medium range Dornier Do 217K-2 bomber on almost all of

its attack missions, though in a few cases toward the end of its

deployment history, Dornier Do 217K-3 and M-11 variants were also

used. Fritz-X had been initially tested with a Heinkel He 111 bomber,

although it was never taken into combat by this aircraft. A few

special variants of the troublesome Heinkel He 177A Greif long-range

bomber were equipped with the Kehl transmitter and proper bombracks to

carry Fritz-X and it is thought that this combination might have seen

limited combat service, at least with the combinations known to have

been involved in test drops.

and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henschel_Hs_293

The Hs 293 was carried on Heinkel He 111, Heinkel He 177,

Focke-Wulf Fw 200, and Dornier Do 217 planes. However, only the He 177

(of I./KG 40 and II./KG 40), certain variants of the FW 200 (of

III./KG 40) and the Do 217 (of II./KG 100 and III./KG 100) used the Hs

293 operationally in combat.

The key issue of both the Hs 293 and Fritz-X effectiveness was Allied Radar directed fighter protection.

After Salerno, Allied radar directed fighter interception pretty much made impossible the use of these weapons as the German missile carrying bombers had to either fly straight and level (Hs 293 glide bomb) or Climb and slow down (Fritz-X vertical bomb) to keep their weapon’s flares in line of sight.

The key word there is Radar.

At Anzio the Germans dropped dipole radar reflectors — chaff in modern terms — and actively jammed the 1.5 meter radar band which most Allied early warning and fire control radars were clustered around.

This gave the Germans a couple of months of effective bombing capability in the Anzio campaign and let them bomb the heck out of the port and shipping because there was no air field at Anzio — which was under observed artillery fire — to park Allied fighters on nor was their any way to effectively direct fighter CAP sent from Southern Italy with the jamming.

It was the arrival of the SCR-584 and SCR-545 microwave fire control radars that turned the tide in the air at Anzio as they could direct defending anti-aircraft artillery far better than an un-jammed SCR-268 searchlight/fire control radars (or its upgraded SCR-516 variant) and were perfectly capable of directing day and night fighters.

This Anzio “Radar shock” had major effects on US and UK Radar development. The US Signal Corps long wave SCR-627 ground control intercept radar (to replace both the Army/Marine SCR-527 and USAAF SCR-588) and SCR-636 air transportable medium range radar (to replace the Australian LW/AW radar for MacArthur) sets were cancelled and suffered truncated production respectively.

The SCR-602/AMES Type-6 1.5 meter light weight radar was very quickly developed into the decimeter band radars AN/TPS-1 (25cm), AN/TPS-2 (75cm) and AN/TPS-3 (50cm).

The British AMES Type-11 (50CM) was placed on the three fighter directer tenders for the Normandy invasion fleet just in case the Germans jammed longer wave length radars.

The SCR-584 wound up in the American Fighter Wing radar units and

Tactical Air Commands (TAC) in both Italy and Northwest Europe.

The Radiation Lab Microwave Early Warning (MEW or AN/CPS-1) radar got it’s A-bomb level priority based on the Anzio radar shock that only just got it ready in time to control air traffic over Normandy.

Minus the “Anzio radar shock,” the Allied ability to control the air over Normandy would have been heavily truncated and the ability of KG40 and KG100 to get at allied shipping greatly enhanced.

For those interested in the background of the German guided bombs see the following bibliography —

1. The Dawn of the Smart Bomb

Technical Report APA-TR-2011-0302

by Dr Carlo Kopp, AFAIAA, SMIEEE, PEng

26th March, 2011

Updated April, 2012

Text © 2006, 2011 Carlo Kopp

http://www.ausairpower.net/WW2-PGMs.html

This article has the the number of Fritz-X built —

“Around 1400 Fritz-X rounds were build, with around half expended in

trials and training.”

2. The Kopp article also links to this piece:

Guided German air to ground weapons in WW2

On special German WW2 Air to ground weapons

Text by 1JMA founder Friis

http://www.1jma.dk/articles/1jmaluftwaf … eapons.htm

That states —

“During the entire Hs 293 development program about 1900 weapons were

build purely for testing and modifications. Some of these were

modified for active service later.”

3. See also this link for warships hit by German guided weapons —

http://www.ausairpower.net/Warship-Hits.html

4. And finally, see William Wolf’s “German Guided Missiles: Henschel

Hs 293 and Ruhrstahl SD 1400X “Fritz X”” which is translated from the

original German and offered as Merriam Press Military Monograph MM53

here:

http://www.merriam-press.com/germanguidedmissiles.aspx

This is the first account to be published in English of two

relatively little-known “secret weapons” of the Luftwaffe.

The Hs 293 guided missile was used against Allied shipping and

naval forces in the latter stages of the war with some success.

Covers development and operational history of the Hs 293 in

considerable detail, as well as proposed variants and the tactics used

against their targets.

Although not as well known as the Hs 293, the Fritz X guided

missile could have dealt considerable havoc on Allied warships and

merchant shipping during World War II, and did achieve some

operational successes.

Covers development and operational history of the Fritz X in

detail, and tactics used against their targets.

Contents

ӢIntroduction

ӢHenschel Hs 293

”¢Ruhrstahl SD 1400X “Fritz X”

ӢAppendices

â—¦Allied Intelligence Report on the Henschel Hs 293

â—¦Allied Intelligence Report on the SD 1400X “Fritz X” Radio-Controlled Bomb

ӢBibliography

Specifications

ӢFourth edition (February 2006)

”¢88 – 6 × 9 inch pages

”¢Paperback: ISBN 978-1-57638-028-4 ”” $14.95

PDF file on disk by mail $1.99

Ӣ13 photos

Ӣ6 illustrations

Ӣ7 multi-view drawings

Ӣ2 cutaways

Ӣ3 camouflage/markings drawings

Ӣ7 side view drawings

Trent,

You really need to get all your articles together in a book. Your research is amazing.

This comment about the German jamming at Anzio totally changes my understanding of that campaign and I have never seen it anywhere else.

Trent, you do really need to get this into book form.

Lex,

This is very much a matter of “lanes” and “Established narrative.”

That bit about jamming at Anzio was heavily classified at the time and outside the “Army, Bomber Mafia and US Navy’s established narrative lanes” after the war, beyond some institutional chest beating by the MIT Radiation laboritory.

Even most historians now-a-days look at general established narrative for most of their work and pick and choose bits and pieces to make their own contribution.

I come at it from a “different methological perspective” in that a great deal of what ground and naval commanders did or didn’t do came from the application of radar.

You might as well ask, “Why wasn’t MacArthur ready for the Korean War?” Tho’ you do seem quite the fanboi. Interesting bits and pieces, but far too much the fanboi. MacArthur was a blustering blowhard who had a first-rate press corps.

For this particular technology, the answer is, “It was far too expensive and too unreliable for what it did for it’s time.” Period. The idea didn’t simply die until resurrected in the last decade or two. The idea was just too far ahead of what engineering could reasonably accomplish at the time, similar to how USA/USAF/USN turf wars between WWII and the Korean War weren’t the cause of the real-world failures of USAF/USN missiles in the early years of the Vietnam War.