Starting seventy five years ago in March 1942, in the aftermath of the February 1942 raid on Darwin by Japan’s dreaded Kido Butai Carrier Fleet, land based air units of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army Air Forces began a sustained campaign to keep Darwin suppressed as a forward operating base for the Allied militaries in Australia. To stop this onslaught, the newly formed and radar equipped Australian No. Five Fighter Sector, RAAF, together with the US Army Air Force 49th Fighter Group fought a lonely and forgotten campaign of aerial attrition that was a tactical draw and an operational victory for General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Theater.

This operational level victory saw the first aerial combined-arms team in the Pacific theater with a radio-telecommunications based command and control organization that melded radar, signals intelligence, ground based observers, ground based air defense, combat engineering, and logistics to meld into an aerial fighting style unique to MacArthur’s theater. A style tactically years in advance of the USAAF in North Africa and Northwest Europe and months in advance of USMC air units over Midway and Guadalcanal. The isolation of this campaign from the USAAF high command also highlighted the fact that the US Army Air Force’s pursuit — AKA fighter pilot — faction was well aware of how to get and maintain air superiority…without the interference of the bomber-faction-dominated USAAF high command.

Figure 1 — 49th Fighter Group P-40 fighters in Darwin, Photo Credit — Australian War Memorial.

Darwin: Setting the Stage

Brian Weston in 6 September 2017 post at “The “Strategist” — The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Blog — titled “The USAAF 49th Fighter Group over Darwin: a forgotten campaign” lays out the first half of the Darwin Air Campaign fought by the USAAF’s 49th Fighter Group.

The prelude to the campaign of the 49th Fighter Group covers some of the darkest days of the Pacific War: the fall of Singapore on 15 February; the bombing of Darwin on 19 February during which the Japanese shot down nine of the ten P-40s of Major Floyd Pell’s 33rd Pursuit Squadron; and the sinking of the USS Langley (CV-1) on 27 February, taking with it thirty-two P-40s and thirty-three pilots from the USAAF 13th Pursuit Squadron.

With the Netherlands East Indies and Philippines lost, American reinforcements, including three USAAF fighter groups—two with the Bell P-39 and one with the Curtis P-40E—were reconstituting in Australia. In March, the most advanced group, the 49th Fighter Group, commenced its move to the Top End, where US and Australian units were feverishly constructing airfields and associated facilities. By April, the 49th, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Paul Wurtsmith, was in situ, with its three squadrons, the 9th, 8th and 7th, located at Livingstone, Strauss and Batchelor, respectively.

Wurtsmith was a career officer, specialising in ‘pursuit’ operations. He was a graduate of the USAAC Tactical School with 4,800 flying hours. His executive officer, Major Don Hutchinson, was another pursuit specialist with 2,500 flying hours. The 49th Fighter Group was fortunate to have such experienced leaders, plus a handful of veterans from the Philippines campaign, but that only masked the inexperience of the group, as out of its initial strength of 102 pilots, 95 had never flown the P-40 before.

Supported by the RAAF No. 5 Fighter Sector with its radars at Dripstone Caves (No. 31) and Point Charles (No. 105), and with the sector now including personnel from the USAAF 49th Fighter Interception Squadron, the 49th’s sixty P-40s provided Darwin with its only fighter defence from March to September 1942 against a threat mainly comprising fast and well-armed Mitsubishi G4M ‘Betty’ bombers escorted by Mitsubishi A6M ‘Zero’ fighters.

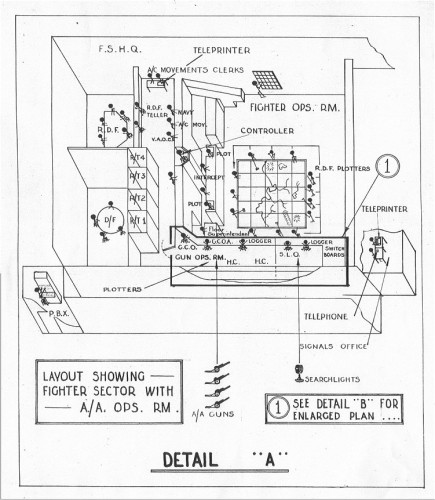

Figure 2 — Typical Royal Australian Air Force “Fighter Sector ” command and control center similar to the one used by the No. 5 Fighter Sector— Source Oz@War

The Rise of Wurtsmith

The key figure in the above passage from Brian Weston is Lieutenant Colonel Paul Wurtsmith. He was a Major at the start of World War II and ended it a Major General. He went from commanding the 49th Fighter Group at Darwin to commanding the Vth Fighter Command in New Guinea and ended up commanding the 13th Air Force at war’s end.

Figure 3 — Major General Paul B. Wurtsmith, Source Wikipedia

There were a lot of reasons for that rise. Paul Wurtsmith was one of the few high-flight-time pursuit pilots that did not get forced out along with Captain Claire Chennault in the 1930s by General Westover’s and later General Arnold’s “Bomber Baron” purge of the pursuit pilot faction in the US Army Air Corps. This placed him at the right place at the right time with the correct experience and training to lead the 49th Fighter Group, with an integrated air defense organization that benefited heavily from the “lessons learned” by American observers of the RAF during the Battle of Britain. Something that Australian author Anthony Cooper made clear in his paper Darwin 1942: The Missing Year:

The USAAF had deployed a remarkably sizeable and capable integrated force to Darwin to secure its air defence: the 808th Engineer Battalion and the 43rd Engineer Regiment to build the airfields, the 102nd Coastal Artillery Battalion to defend those airfields against strafing attacks, the 49th Fighter Group to provide fighter defence, the 49th’s Fighter Interception Squadron to provide ground-based fighter control, and the 43rd Material Squadron to maintain the P-40s and top up the 49th’s aircraft inventory. Nowhere else in the South West Pacific Area particularly in Port Moresby was there such a deeply resourced and vertically-integrated fighter deployment.

The failed Allied campaigns in the Philippines, Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies, Burma and New Guinea vividly emphasised the preconditions for successful air defence an effective air force needed a network of airfields, and those airfields had to be made resilient (to some extent ‘bomb-proof’); there had to be a network of radar stations to provide reliable early warning, and the radar plotting data had to be filtered through an air defence operations room, with a controller able to ‘scramble’ the fighters and to use radio to provide in-flight directions; and the fighter force needed to be made resilient by the provision of a deep maintenance and supply organisation able to maintain the aircraft inventory despite losses.

The American deployment around Darwin showed clear recognition of all these essential elements and stood in stark contrast to their humiliating debacle in the Philippines and to their improvised deployment to Java,

This well integrated air defense organization was no accident. The 1930s USAAF pursuit faction was very well versed and professional on issues of air defense. Claire Chennault studied German WW1 fighter tactics closely and kept abreast of radio development for adding fighter direction capability to ground-observer early warning networks. (This is mentioned early, pages 20-23, in his memoirs “Way of a Fighter: The Memoirs of Claire Lee Chennault“)

It turns out that the British ground observer network for the Battle of Britain in WW2 with telephones and radio was an outgrowth of their London telephone and ground observer anti-Zeppelin defenses of WW1. (See Amazon.com for ” Churchill’s War Against the Zeppelin 1914-18: Men, Machines and Tactics” which addresses this system in wider coverage of Churchill as Lord of the British Admiralty in WW1.)

The primary role of this British network, that the US Army Air Corps copied in the 1920s, was to warn the civilian populace to take cover. Like Chennault, and quite independently, the RAF worked to upgrade the ground observer network in the 1930s into something that could track bombers and control fighter intercepts by radio.

Chennault, as an instructor at the Army Air Corps Air Tactical School in the early 1930s, closely studied the aerial tactics of Oswald Boelcke and Manfred von Richthofen during their reign as leaders of the Imperial German “Flying Circus” and especially their emphasis on two-plane elements and a very calculated aerial teamwork approach to attack from higher altitude and separate, as opposed to individual dogfighting.

He taught these tactics to the early to mid-1930s cohort of Air Corps pursuit pilots including one Paul Wurtsmith.

The Fall of Chennault

During this time as Air Tactical School instructor, Captain Claire Lee Chennault challenged the report of one Lt. Col “Hap” Arnold regarding “bombers always getting through” in the 1931 Air Corps maneuvers. In particular over the inability of fighters to intercept the then-new B-10 bomber. Chennault raised such a stink that in the 1933 maneuvers, he was allowed to put together his air defense ground observer network to shut him up. That is, no one in power in the Air Corps believed he was right, and they assumed his failure would ruin him.

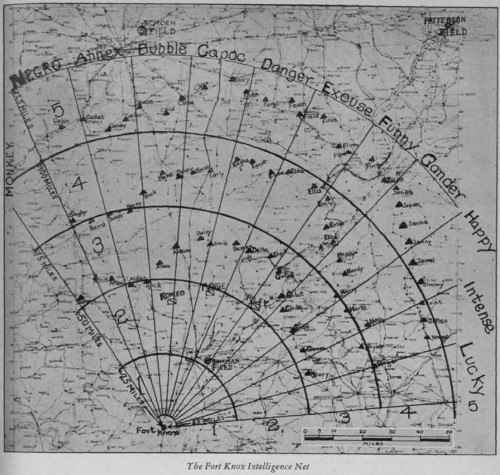

The issue for the Bomber Faction was that Chennault was right. He embarrassed the hell out of the Bomber Faction during the 1933 Ft. Knox maneuvers by intercepting every bomber flight dispatched from Dayton, Ohio.

This pre-war failure of the Bomber Mafia has been removed from the institutional narratives in the founding of the USAF along with Chennault and many of his supporters.

What motivated this purge was issues of budget. The B-17 “Flying Fortress” was so named because the Air Corps wanted the Coast Defense mission budget and was implying that the 4-engine bomber could replace the system of Coast Artillery branch fortresses.

When Chennault detailed in three articles in the US Army’s Coast Defense Artillery branch publication why that was not so, it was very much an attack on the Bomber Faction’s vital interests.

These articles are online and I mentioned them in my Dec 20, 2013 column “History Friday: Claire Lee Chennault — SECRET AGENT MAN!”. The figure below is from the Nov-Dec 1933 Chennault article.

Figure 4 – Then Captain Claire Chennault’s 1933 Ft. Knox Air Defense Observer Network. It was so successful in catching bombardment formations that Chennault was black balled by the “Bomber Mafia” under two Air Chiefs of Staff. Photo Source: Coast Artillery Journal Mar-Apr 1934, pg. 39

In the aftermath of Chennault’s 1933 success and Coast Artillery Branch article series, he was removed as an instructor from the Air Tactical School along with his syllabus of tactics.

The RAF style of three-plane “Vics” with wingmen on either side of the lead pilot flying in tight aerobatic formation succeeded the combat tested two-plane element at the Air Tactical School.

This suite of flawed fighter tactics killed a lot of British pilots in the Battle of Britain and contributed heavily to the failed American aerial defense of both the Philippines and Java.

These moves so dispirited Chennault that he took a 20-year disability retirement in 1937. This ‘forced’ retirement lead directly to his being offered a job as an air warfare consultant for the Nationalist Chinese government and the rest, as they say, is well publicized “Flying Tiger’s” history.

Chennault’s Combat Legacy at Darwin

Despite the “Bomber Faction” purge of Chennault and his syllabus, there was a legacy of trained pursuit pilots left behind that used his training. This legacy made itself felt at Darwin in 1942, as Australian author Anthony Cooper makes clear here:

The 49th had started its tour of duty in Australia as a very inexperienced unit filled with very green pilots. Out of the group’s initial complement of 102 pilots, 95 had never flown a P-40 before.62 It was fortunate that the Japanese rearward redeployments provided such a long pause in combat operations, giving the opportunity for the junior pilots to be drilled in scrambles, airborne rendezvouses, fighter formation and gunnery.63 The group CO, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Wurtsmith, was a professional fighter leader with 14 years experience in ‘pursuit’ and 4800 flying hours, while his executive officer, Major Donald Hutchinson, was another ‘pursuit’ specialist, with 2500 hours. 64 The professional officers at the head of the 49th were supported by 15 war-experienced pilots from the campaigns in the Philippines and Java.65 These men taught their inexperienced charges the distilled lessons of war experience so far: flying in ‘two-ship’ formations for mutual protection and always attacking from above. 66

LtCol Paul Wurtsmith Innovates Fighter Direction

While the two-plane element and attack-from-above doctrine was from Chennault, LtCol Wurtsmith came into his own as an aerial tactician with the use of Australian radar. He developed with his group a unique-to-the-South West Pacific “dialect” of fighter direction. His pilots used “running commentary” from his ground radars to direct his fighters, in four-plane “sections” made up of two-plane “elements”, to intercept high flying “Betty” Bombers escorted by A6M “Zeke” fighters.

These four-plane sections were harder to see than the squadron formations that the British used in the Battle of Britain and USMC Major Floyd B. Parks, VMF-221, used at Midway, allowing American planes to get closer to fighter-escorted bomber formations, from multiple directions, and thus allowing more defending fighters to break through. Again from Anthony Cooper:

The Americans had used very similar tactics to those used from 25 April onward. The flights flew separately, led by junior officers usually 2nd Lieutenants who listened to the controller’s running commentary and used their initiative in maneuvering into the most advantageous possible position before attacking. These flights attacked successively from different directions, presenting the escorting fighters with the difficulty of covering multiple attack axes. Moreover, the tiny 3 or 4-ship P-40 formations were inconspicuous in a big sky, maximising their chance of getting in unobserved and making surprise attacks. The weather had helped too, for the combat area was studded with cumulous clouds, splitting the bombers from their escorts and enabling the small American formations to approach without being seen.

The SWPA Fighter Control Dialect

I’ve written before in my 2014 column History Friday — Operation Chronicle and Airspace Control in the South West Pacific about how MacArthur’s theater had its own fighter-control procedures apart from the mainstream of Anglo-American practice. This was based upon Ed Simmonds’s and Norm Smith’s, “ECHOES OVER THE PACIFIC: An overview of Allied Air Warning Radar in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines Campaign”. What I discovered with Anthony Cooper was the American contribution to this dialect.

“Running Commentary” was one of two types of fighter control in WW2. It was independent of controlling the fighters and simply let the fighter pilots work out the intercept by providing them with the course, speed and altitude of an incoming raid. This method was used extensively by German night fighter controllers when the RAF jammed their ground based radars and radios in 1943-45 and by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm in 1940-41.

The other form of fighter control — “Directive Control” — put fighters on a tight leash telling them course, speed and altitude and was the preferred RAF Fighter Command fighter direction method. This was widely copied by the USAAF, US Navy and Royal Navy in 1942-43 when 100-mile (161KM) Very High Frequency (VHF) radios became available. It was the VHF radio that was the heart of this control method.

Planes in MacArthur’s theater, however, had to rely upon 50-mile-range (80-km) Australian made high frequency (HF) into 1944 for logistical reasons I laid out in my Operation Chronicle column. So the Wurtsmith “Running Commentary” fighter direction dialect hung on until the Philippines Campaign.

A Forgotten Hero

It would be nice to say that Gen Paul Wurtsmith went on to greater glory after WW2…but he didn’t.

He died in a 1946 air crash in bad weather, flying a B-25 into a North Carolina mountainside.

And the story of his Darwin innovations, and why they came about, were too…politically incorrect… for the newly independent USAF to tell.

Hopefully, this 75th anniversary column will renew interest in the exploits of this fallen hero.

-End-

=====

Sources and Notes:

Way of a Fighter: The Memoirs of Claire Lee Chennault, by Claire Lee Chennault

https://www.amazon.com/Way-Fighter-Claire-Lee-Chennault/dp/7538745939

‘Darwin 1942: the missing year’ By Anthony Cooper

http://www.territoryremembers.nt.gov.au/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/collection%20of%20stories/anthony_cooper.pdf

Finger-four, Wikipedia article

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finger-four#Other_operators

Marines at Midway, Chapter 4: The Battle, 4-5 June 1942, Marines in World War II Historical Monograph by Lieutenant Colonel R.D. Heinl, Jr., USMC, Historical Section, Division of Public Information, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps 1948

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/Midway/USMC-M-Midway-4.html

Royal Air Force Tactics During the Battle of Britain

http://www.classicwarbirds.co.uk/articles/royal-air-force-tactics-during-the-battle-of-britain.php

History Friday — Operation Chronicle and Airspace Control in the South West Pacific

Posted by Trent Telenko on 25th April 2014

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/42554.html

History Friday — MacArthur’s Anglo-Australian Radars

Posted by Trent Telenko on June 28th, 2013

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/37020.html

The USAAF 49th Fighter Group over Darwin: a forgotten campaign

posted by Brian Weston 6 Sep 2017

https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/usaaf-49th-fighter-group-darwin-forgotten-campaign/

The 5th Fighter Command in World War II, Vol. 3: 5th FC vs. Japan – Aces, Units, Aircraft, and Tactics 1st Edition, pages 1218-1221, by William Wolf, ISBN-10 – 0764347381, ISBN-13 0 978-0764347382, Schiffer Military History, October 28, 2014

https://www.amazon.com/5th-Fighter-Command-World-Vol/dp/0764347381

Vic formation, Wikipedia Article

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vic_formation

Paul Wurtsmith, Wikipedia Article https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Wurtsmith

Great post, Trent.

I knew that relations between the US Army and Navy have traditionally been poisonous. I hadn’t realised the differences within the Army Air Corps: ‘purge of the pursuit pilot faction in the US Army Air Corps’. Oof!

I knew a bit of the background of the Chennault vendetta by the Bomber Mafia.

Thanks for filling some gaps.

I wonder how this affected the “Cactus Air Force” in 1942 ?

There have been multiple small edits of format and sources. additionally, a fifth figure added to show the “Vic” formation.

The wikipedia article on the “Finger Four” mentions that the USAAF and USN transitioned to the two element formation in 1940-41.

This is incorrect as P-47 groups trained in the USA and deployed to the XIIIth Air Force Fighter Command after Operation Torch stripped the 8th Air Force of all but one fighter group had to be retrained by the RAF to use the “Finger four” during their “Rhubarb” fighter sweeps in 1942-43.

Mike K,

Regards this —

>>I wonder how this affected the “Cactus Air Force” in 1942 ?

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thach_Weave

Overcoming the Wildcat’s disadvantage[edit]

Thach had heard, from a report published in the 22 September 1941 Fleet Air Tactical Unit Intelligence Bulletin, of the Japanese Mitsubishi Zero’s extraordinary maneuverability and climb rate. Before even experiencing it for himself, he began to devise tactics meant to give the slower-turning American Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters a chance in combat. While based in San Diego, he would spend every evening thinking of different tactics that could overcome the Zero’s maneuverability, and would then test them in flight the following day.[citation needed]

Working at night with matchsticks on the table, he eventually came up with what he called “Beam Defense Position”, but which soon became known as the “Thach Weave”. It was executed either by two fighter aircraft side-by-side or by two pairs of fighters flying together. When an enemy aircraft chose one fighter as his target (the “bait” fighter; his wingman being the “hook”), the two wingmen turned in towards each other. After crossing paths, and once their separation was great enough, they would then repeat the exercise, again turning in towards each other, bringing the enemy plane into the hook’s sights. A correctly executed Thach Weave (assuming the bait was taken and followed) left little chance of escape to even the most maneuverable opponent.

Thach called on Ensign Edward “Butch” O’Hare, who led the second section in Thach’s division, to test the idea. Thach took off with three other Wildcats in the role of defenders, O’Hare meanwhile led four Wildcats in the role of attackers. The defending aircraft had their throttles wired (to restrict their performance), while the attacking aircraft had their engine power unrestricted – this simulated an attack by superior fighter aircraft.[1]

Trying a series of mock attacks, O’Hare found that in every instance Thach’s fighters, despite their power handicap, had either ruined his attack or actually maneuvered into position to shoot back. After landing, O’Hare excitedly congratulated Thach: “Skipper, it really worked. I couldn’t make any attack without seeing the nose of one of your airplanes pointed at me.”

In combat[edit]

Thach carried out the first test of the tactic in combat during the Battle of Midway in June 1942, when a squadron of Zeroes attacked his flight of four Wildcats. Thach’s wingman, Ensign R. A. M. Dibb, was attacked by a Japanese pilot and turned towards Thach, who dove under his wingman and fired at the incoming enemy aircraft’s belly until its engine ignited. The maneuver soon became standard among US Navy pilots and was adopted by USAAF pilots.

Marines flying Wildcats from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal also adopted the Thach Weave. The tactic initially confounded the Japanese Zero pilots flying out of Rabaul. SaburÅ Sakai, the famous Japanese ace, relates their reaction to the Thach Weave when they encountered Guadalcanal Wildcats using it: [2]

“For the first time Lt. Commander Tadashi Nakajima encountered what was to become a famous double-team maneuver on the part of the enemy. Two Wildcats jumped on the commander’s plane. He had no trouble in getting on the tail of an enemy fighter, but never had a chance to fire before the Grumman’s team-mate roared at him from the side. Nakajima was raging when he got back to Rabaul; he had been forced to dive and run for safety.”

The maneuver proved so effective that American pilots also used it during the Vietnam War, and it remains an applicable dogfighting tactic today.[3]

The material on the 22 September 1941 Fleet Air Tactical Unit Intelligence Bulletin came from Chennault.

Chennault had a working relationship with Naval technical intelligence in China that was in part responsible for the sinking of the American gunboat USS Panay.

I had a book on “The Cactus Air Force” that I gave to a friend who had flown Corsairs from Henderson Field in 1943 and 44. He died a year later. I wish I had that book. Amazon lists hardcover copies at $70 and new hardcover at $600.

The “Thatch Weave” was famous but I had not seen the Japanese pilot’s remark.

Trent, I read the Wiki article on the Thach Weave anbd then the article on Butch OHare.

The cause of his death has been controversial for many years. Alvin Kernan was the TBF turret gunner that night and for years was accused of shooting down OHare in a “friendly fire” incident.

After the war, Kernan went to college and ended up a dean of the Graduate School at Princeton. He has written several excellent books on the Midway battle and has defended himself on the death of OHare. The Wiki article includes a reference to a more recent book that absolves Kernan and describes the shoot down of OHare as Japanese gunfire from the Betty they were attacking. It was the first attempt at night fighter tactics in the Pacific and there were multiple problems. The P 61 came along later and did a better job.

Mike K,

I’ll note here that Wurtsmith’s P-40’s were fighting the Japanese with two-plane elements in April and May 1942 over Darwin prior to Thatch at Midway.

I’d say Wurtsmith was a more capable air leader simply from,

a. Having to fight far more of the experienced top line Japanese Naval aviators, before attrition wore them down prior to Guadalcanal, with

b. An airplane — the P-40 — with poorer high altitude performance than the Wildcat.

Half the initial pilots of the Rabaul based fighter unit used at Guadalcanal had died killing RAF, RAAF, Dutch and USAAF pilots in the first six months of the war.

Wurtsmith’s 49th Fighter Group was the only unit to get one-to-one kill ratios on land based JNAF pilots in that December 1941 through May 1942 period.

Chennault’s Flying Tigers faced JAAF planes for the most part.

Interesting. I’ve not read a comparison of P 40 and F4F.

Here is one discussion.

One commenter says the Flying Tigers did not fight Zeros but the link is dead. I don’t know what that is about.

IIRC, The F4F had two superchargers on it’s radial engine while the P-40 only has one on it’s liquid cooled engine.

The later escort carrier FM-1 and FM-2’s built by GM lacked that second supercharger.

This meant the F4F had a higher critical altitude, aka more horsepower at high altitudes, and a higher ceiling overall.

Mike K, thanks for the link.

May I recommend “America’s Hundred Thousand” by Francis Dean, if you don’t already have it. It is loaded with comparative performance data on US WWII fighters. Interesting too are the pilots’ comments the AC and their handling.

“America’s Hundred Thousand” by Francis Dean,

Doesn’t come up on amazon.com/

Maybe this will help?

https://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss_2?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=america's+hundred+thousand&rh=n%3A283155%2Ck%3Aamerica's+hundred+thousand