One of the strangest experiences doing historical research is following a trail of research on something you think you know, and then suddenly you go down Alice’s rabbit hole and find a “detailed reality” that was something completely different. So it was researching General Claire Chennault’s ground observer network in World War II (WW2). I went looking for the nuts and bolts organizational creation of an air power genius…and what I found instead was “Claire Lee Chennault — SECRET AGENT MAN!!!”

It turns out that Chennault’s anti-aircraft ground observer network evolved in China from 1937 through 1945 from an air-warning network into a full scale human intelligence service. A human intelligence service that was operationally annexed by General William “Wild Bill” Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the Spring of 1945.

When I started this thread of research, I was looking for a copy of then Captain Chennault’s “THE ROLE OF DEFENSIVE PURSUIT.” The institutional histories of the US Air Force on World War II (WW2) mention the existence of the anti-aircraft ground observer network called for by “THE ROLE OF DEFENSIVE PURSUIT” in China, but not much more. “THE ROLE OF DEFENSIVE PURSUIT” was also mentioned prominently in the first chapter of Paul A. Ludwig’s book “P-51 Mustang: Development of the the Long Range Escort Fighter” which I received as a gift recently, and the author makes the point General Arnold’s Army Air Corps threw out this ground observer network along with the only man in its service that knew the heavy bomber wasn’t invincible. They did so for the heresy of speaking that truth.

The lack of historical coverage of a past military institution in military institutional histories, and the lack of a modern equivalent to tell their stories, are always good cues to go researching. My internet searches to that end yielded both “THE ROLE OF DEFENSIVE PURSUIT” and an article by Bob Bergin titled “Claire Lee Chennault and the Problem of Intelligence in China,” in the June 2010 issue of Studies in Intelligence. What I didn’t expect to happen by reading the article was to fall down Alice’s “rabbit hole” into an espionage wonderland.

I knew that there was a lot of espionage derring-do involved with the creation of the American Volunteer Group (AVG), getting $8 million in P-40 fighters and a $3 million payroll of mercenary pilots and mechanics past the Japanese Military intelligence, plus the US Military & political naysayers, could not help but have that. The obvious thing I missed was that the organizational infrastructure to use the AVG like a precision instrument required far more espionage derring-do. This included a personal espionage mission to Japan by Chennault on his way to China and a budding alliance with the US Navy intelligence via the US naval attaché to China, who was forwarded by Chennault captured Japanese aircraft parts from downed planes. These parts were put on the US gunboat Panay. The Japanese learned of this and two days later the Panay was “mistakenly” attacked by the Japanese and sent to the bottom of the Yangtze.

Later, between the sinking of the Panay and Pearl Harbor, Chennault built his air warning networks in China, according to Bergin:

With the air defense of Nanking his responsibility, Chennault established the first of his warning nets. All available information on enemy movements was channeled into a central control room and plotted on a map that Chennault used to control the defending Chinese fighters. He adapted the net as the situation changed and the Chinese withdrew to Hangzhou and Chungking.

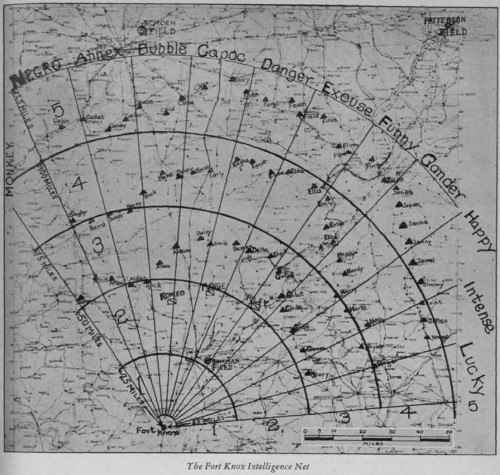

It would take time before the warning net became what he envisioned, “a vast spider net of people, radios, telephones, and telegraph lines that covered all of Free China accessible to enemy aircraft.”7

The methodical development of that spider net began later in Yunnan Province. Four radio stations in a ring 40 kilometers outside Kunming city reported to the control center in Kunming. Each radio station was connected by telephone to eight reporting points, with each of those points responsible for a 20 kilometer square of sky. This pattern was repeated to create additional nets as they were needed, and all the nets were interconnected until there was one vast air warning net spread over all of Free China.

The net was also used to warn civilians of bombing raids and as an aid to navigation. A lost American pilot could circle a village almost anywhere in China and in short order be told exactly where he was—by a net radio station that had received a telephone call from the village he was circling. The net was so effective that Chennault could later say: “The only time a Japanese plane bombed an American base in China unannounced was on Christmas Eve of 1944, when a lone bomber sneaked in…from the traffic pattern of (American) transports circling to land after their Hump trip.”8

The evolution from air warning network to human espionage network was due to one Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, who amidst the vipers nest of the Chinese capitol declared the stale and useless intelligence provided by the Chinese War Ministry to Stilwell’s headquarters in Chungking “good enough” and forbade Chennault’s 14th Air Force from developing a separate intelligence network to get better. This was how Chennault solved the problem:

“I solved this problem by organizing the Fourteenth’s radio intelligence teams within the framework of our air-raid-warning control network and continued to depend officially on Stillwell’s stale, third-hand Chinese intelligence….”

Enter John Birch

When Jimmy Doolittle raiders were smuggled out of China, they were lead by a young Georgia Baptist missionary named John Birch. Birch became the model field agent for Chennault’s budding field intelligence service operating his air warning service cover. Again, according to Bergin:

Chennault sent Birch back to East China to survey secret airfields and gasoline caches, then went him to work with the guerrillas along the Yangtze River. He recruited agents to report on Japanese shipping by radio and developed target information on his own. Once, when the bombers could not find a huge munitions dump hidden inside a village, Birch passed back through the Japanese line, joined the bombers and rode in the nose of the lead aircraft to guide them directly to the target target.

Birch pioneered the techniques to provide close air support to ground troops. He served as a forward air controller and with a hand-cranked radio talked aircraft down on their targets.

Birch was adept at moving through Japanese lines and became the example for those who followed. He dyed his hair black, dressed as a farmer and learned how to walk like one. He carried names of Chinese Christians to contact in areas he operated in. Church groups became his infrastructure behind the lines, providing food, helpers and safe places to stay. He remained in the field for three years, refusing any leave until the war was over, he said.

Wild Bill Comes Calling

In December 1943 General William Donovan came to China to try and disengage his OSS operatives from the KMT Secret Police inside SACO, a joint intelligence organization between America and the Nationalist Chinese that came to be dominated by US Naval intelligence. This was not possible and Chennault provided an alternative.

This OSS-Chennault alliance took the form of the 5329th Air and Ground Forces Resources and Technical Staff (AGFRTS — or Agfarts, as it became known). The 5329th combined OSS and the Fourteenth’s field intelligence staff, with the addition of OSS Research and Analysis personnel. Additional Operational Researchers also came from the Office of Scientific Research and Development and were involved in RADAR intelligence.

The “5329th AGFRTS” assumed all intelligence duties of the Fourteenth Air Force through the end of the war.

An End With a Whimper and a New Beginning.

The way Bergin tells this story, Chennault simply lost interest with the 5329th in the final year of the war. It would be more accurate to say that the crisis that was the Japanese Ichi-Go offensive against the Nationalists consumed Chennault’s attention until the death of President Roosevelt, his biggest and only patron in the American high command.

With Roosevelt’s death, Chennault’s time in senior high command in China was limited. Chennault still had the enmity of General Arnold as Army Air Force chief of staff. Chennault’s earlier victory over his nemesis General Stillwell of behalf of Nationalist leader Chang-Kai-shek also cost him the enmity of General Marshall, of whom Stillwell was a protege.

The only ally Chennault could call on was Donovan…except that Arnold had acted ahead of Roosevelt’s death to head that off. In March 1945 he supported Donovan getting the OSS a part of the invasion of Japan action with a radio tel-operated robotic boat bomb called Javaman. The Javaman was intended to close the Kanmon Railway Tunnel under the Shimonoseki Straits between Honshu and Kyushu, Japan.

Without a patron, Chennault returned to the USA after his ouster. Not one to ever give up a fight, he quickly resigned his commission and returned to China to found “Civil Air Transport,” an airline that supported the Nationalist cause in the ensuing Chinese Civil War. A civil war in which his now OSS owned spy network was wiped out by the Chinese communists. Included in those casualties was one John Birch.

Chennault was subsidized operating, and was later bought out of owning “Civil Air Transport.” The principal that wound up owning “Civil Air Transport,” and later renamed it AIR AMERICA, was the Central Intelligence Agency, the successor agency to the OSS.

Thus ends a tale of research that started looking for Chennault the air-power genius and ends going through the “Rabbit Hole” and finding Claire Lee Chennault — SECRET AGENT MAN!

Notes and Sources:

Bob Bergin, “Claire Lee Chennault and the Problem of Intelligence in China,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 54 No. 3 (June 2010) Pages 1 – 40. www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA523664”Ž

Captain Claire Lee Chennault “THE ROLE OF DEFENSIVE PURSUIT,” Serialized in the Nov-Dec 1933, Jan Feb 1934, and Mar-Apr 1934 issues of the US Army’s branch publication “Coast Artillery Journal”

Claire Lee Chennault “The Way of a Fighter,”ed. Robert Holtz (New York: GP Putnam,1949)

Paul A. Ludwig, “P-51 Mustang: Development of the the Long Range Escort Fighter,” Classic Publications, am Imprint of Ian Allen Printing Ltd, Hersham,Surrey KT12 4RG, copyright 2003, ISBN: 1-903223-14-8 pages 14-26

Joseph E. Persico’s “Roosevelt’s Secret War; FDR and World War II Espionage” Random House Trade Paperbacks (October 22, 2002) ISBN-13: 978-0375761263

Great stuff.

Thanks, Trent.

I had read other stories about how Chennault had pissed off the bomber mafia in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but I had not realized how deep the it was.

Another fantastic article. Thank you very much.

I read military history from a certain POV. Your work is invaluable. You really must do a book, or a book in blog form.

I’ll kick up to Kickstarter for that..

Ralph Lee De Falco III, wrote a great essay titled ‘ Blind to the Sun: U.S. Intelligence Failures Before the War with Japan . – In that essay DeFalco gives full credit to Chennault for being one of the few who correctly assessed Japan war making capabilities. The essay was published in the Spring 2003 edition of the Int’l Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence .

The De Falco article came up on my first internet search with the title, author and publication as my search terms. It is very much worth a read.

This was one of the foot notes:

Chennault’s method of analyzing, disseminating, and using intelligence was far superior to anything accomplished by the armed forces of the United States during the same period. Chennault lectured for hours from his detailed notebooks and trained his pilots to recognize Japanese flight tactics. Pilots were then thoroughly briefed on the construction, performance, and armament of every Japanese aircraft they might encounter. Chennault gave every pilot mimeographed data sheets on the enemy’s aircraft. This was followed by sessions at a blackboard where Chennault diagrammed the vital spots of Japanese aircraft””oil coolers, bomb bays, gas tanks””in colored chalk.

.

Erasing the board, Chennault then had pilots redraw the diagrams from memory. The results speak volumes about Chennault’s use of intelligence: Under the most daunting conditions, and in less than six months, the American Volunteer Group would be credited with 297 confirmed kills against the combat loss of only 14 of their own aircraft.