The Okinawa campaign in WW2 has often been described as marking the end old style total war. Where “cork screw and blow torch” close combat to the death between American attackers who fought to live and Japanese defenders who died in order to fight played out its last dance.

Upon closer examination, as this first article in a series planned to run through August 2018 will demonstrate, the Imperial Japanese were a fell World War 2 high tech foe, punching in a weight class above the Soviet Union. In high tech warfare, as in everything else, the Samurai clan dominated Japanese military was smart, driven, capable, and deadly. Their culture was obsessive about doing everything their own way, partly copying, but always obsessive about the Japanese originality of the design. Whether we are looking at the Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighter, the 72,000 ton and 18-inch gun armed Yamato Class battleships or the I-8 and I-400 class submarine aircraft carriers. These innate skills as high tech warriors meant Okinawa was in many ways far better described as a high tech war for the electromagnetic spectrum between peer competitors.

Point in fact, Okinawa was a “secret radar war” where two opposing command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I) sensor networks were directing land, sea and air forces in a series of moves and counter moves. And while the less technologically advanced, and organizationally deficient, Japanese military lost Okinawa proper. It still took advantage of US Navy institutional biases, American inter service rivalries, political weaknesses, US Naval high command unwillingness to learn from “non-approved” sources and most especially its operational security failures to defeat the US Navy’s original plan to overrun the Ryukyu’s. Denying the American military the Northern Ryukyu air bases it originally sought to cover the proposed Operation Olympic landings.

The first block in that Japanese Pyrrhic electronic warfare victory at Okinawa was laid at Bombay Shoal, off Palawan in the Philippines. Where the USS Darter sank Japanese Admiral Kurita’s flagship the heavy cruiser IJNS Atago during the greatest naval victory in America’s History, the Battle of Leyte Gulf. And Japan had its biggest windfall of captured American secret radar documents in World War 2 — and second biggest secret document windfall over all — from Atago’s killer.

THE OFFICIAL USS DARTER NARRATIVE

The following passage is from Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships and it describes The USS Darter’s victory and grounding below —

Returning to Brisbane 8 August 1944, Darter cleared on her fourth and last war patrol. She searched the Celebes and South China Seas, returned to Darwin to fuel and make minor repairs 10 September, and put back to the Celebes Sea. She put in to Mios Woendi 27 September for additional fuel, and sailed on 1 October with Dace (SS-247) to patrol the South China Sea in coordination with the forthcoming invasion of Leyte. She attacked a tanker convoy on 12 October and on 21 October headed with Dace for Balabac Strait to watch for Japanese shipping moving to reinforce the Philippines or attack the landing forces.

In the outstanding performance of duty which was to bring both submarines the Navy Unit Commendation, Darter and Dace made contact with the Japanese Center Force approaching Palawan Passage on 23 October 1944. Immediately, Darter flashed the contact report, one of the most important of the war, since the location of this Japanese task force had been unknown for some days. The two submarines closed the task force, and initiated the Battle of Surigao Strait phase of the decisive Battle for Leyte Gulf with attacks on the cruisers. Darter sank Admiral Kurita’s flagship Atago, then seriously damaged another cruiser, Takao. With Dace, she tracked the damaged cruiser through the tortuous channels of Palawan Passage until just after midnight of 24 October when she grounded on Bombay Shoal. As efforts to get the submarine off began, a Japanese destroyer closed apparently to investigate, but sailed on. With the tide receding, all Dace’s and Darter’s efforts to get her off failed. All confidential papers and equipment were destroyed, and the entire crew taken off to Dace. When the demolition charges planted in Darter failed to destroy her, Dace fired torpedoes which exploded on the reef due to the shallow water. As Dace submerged, Darter was bombed by an enemy plane. Dace reached Fremantle safely with Darter’s men on 6 November.

In addition to the Navy Unit Commendation, Darter received four battle stars earned during her four war patrols, the last three of which were designated as “successful”. She is credited with having sunk a total of 19,429 tons of Japanese shipping.

A more recent August 16, 2016 article titled Darter & Dace at the Battle of Leyte Gulf by David Alan Johnson at Warfare History Network expands on the circumstances that caused the seasoned captain of the USS Darter, Commander McClintock, to ground her in the heat of combat. The following happened shortly after Darter and her wolf pack companion USS Dace sank two and damaged one heavy cruiser of Admiral Kurita’s “Center Force” —

They decided to make a surface attack, but expected that the cruiser would be towed by the two destroyers. To everyone’s surprise, Takao got underway under her own power. She began heading southwest at about six knots. This presented a new situation; torpedoing a moving target presented different conditions from shooting a sitting duck, even if the target was only moving at six knots. The two captains would split their attack—Darter would make her attack from the east while Dace made an end run around from the west. By midnight on October 24, the two submarines were still getting into position for their torpedo attack. Darter was making 17 knots, trying to attack before Takao could pick up more speed.

For the past 24 hours, both submarines had been navigating the Palawan Passage by dead reckoning only. Because they had spent so much time submerged during the daylight hours, navigators were not able to get a fix on the mountains on Palawan, which meant that they were not exactly certain of their position. Clouds obscured the stars after sunset, so they were not able to get a celestial fix, either.

To evade the screening destroyers, Commander McClintock planned to leave a margin of seven miles to Bombay Shoal, which is a coral reef on the western side of Palawan Passage. A quarter-knot error in estimating the current put Darter on a collision course with the reef. At 12:05 am, Darter’s crew found out exactly why that stretch of water was called the Dangerous Ground.

The one thing in common about both David Alan Johnson’s and Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships description of events is that they are wrong about USS Darter burning all its secret documents. It didn’t.

This is what Commander McClintock actually said in his log:

“0015 H Jap destroyer now began closing. He must have heard us hit.

Commenced burning secret and confidential matter and destroying

confidential gear. All hands not engaged in destroying gear employed

in lightening ship.”“0230 H Tide receding now. We are high and dry. Ceased effort to get

off. Concentrated on destroying confidential gear. Three fires were

kept burning below decks to destroy classified matter: one in forward

engine room, one in radio shack, one in officer’s shower. These made

much smoke. Smoke was kept down to some extent by running #10 blow

continuously. More fires would have made destruction work below

impossible. As it was, personnel had to go topside for air every few

minutes. All registered publications except ONI-49 destroyed by

burning. Report of confidential matter not burned submitted by

dispatch and will be submitted by separate letter.FOLLOWING GEAR DESTROYED:

1. SJ radar including magnetron tubes

2. SD radar; ABK; BN; ARC

3. Sound gear in forward room; including JP.

4. Sound gear in conning tower.

5. TDC and both gyro angle indicator regulators.

6. Bathythermograph

7. Gyro

8. Ship’s radio transmitters and receivers

9. All generators were burned out (main generators)”

And if fortune favors the well prepared…Commander McClintock made clear his crew wasn’t, because the US Navy as an institution gave them inadequate tools and expected them to improvise the impossible. At pages 216-217 of the on-line logs of USS Darter, Commander McClintock made the following biting remarks:

1. Demolition Outfit: It is recommended that a permanent wiring system for the demolition charges be installed on each submarine at the earliest practiable date. Conditions such as those encountered by the Darter call for this. With lightening the ship, destruction of gear installations below decks, and fires burning, the flimsy wiring provided may easily be damaged; and the wiring available to rig the charges may easily be inadequate, if the ship is left in the presence of the enemy in circumstances where it cannot be sunk.

2. Classified Matter: It is recommended that the number of registered publications carried on board be further reduced. Also that all confidential files except essential letters be turned in prior to departure on patrol . The time taken to burn all the registered publications and confidential charts, let alone ordinary confidential letters, makes this of vital importance.

The bold in the passage above was underlined in the type written original document.

Everything that could go wrong on the USS Darter after she grounded, did so, at the worst possible time. And the boarding parties of the Imperial Japanese Navy captured USS Darter’s complete unburned library of classified documents.

Why that happened has been explained.

The “Who” of it, the Japanese naval commander who seized both fortune’s prize, and Darter’s secret documents, is next

THE MIXED LUCK OF CAPTAIN ONADA SUTEJIRO

In the disaster that was the Battle the Leyte Gulf, Japan was well served by Capt Onada Sutejiro [Etajima 48 Class].

Capt Onada, prior to his command of the IJNS Takao, was heavily involved in Japanese diplomacy. Capt Onada was sent to France 1928-29 and he visited Europe with Admiral OSUMI Mineo Mission in 1939. He again visited Germany in 1943 with Major General OKAMOTO Kiyotomi’s delegation via Siberian Railway. Capt Onada then returned to Japan aboard Japanese submarine I-29 in July 1944.

Through a matter of purest luck, he missed being sunk on the I-29 as after the former docked at Singapore. As it was decided by Japanese naval high command that he should return immediately by air. After leaving Singapore the I-29 was sunk by a submarine, likely cued on to its departure by ULTRA intercepts of the Japanese JN-25 naval code.

Shortly after arriving in Japan, Capt Onada, he was given the IJNS Takao, and the mixed luck that he had at Singapore held at Bombay Shoals

The Darter was stalking Capt Onada’s damaged Takao when she ran aground on the Bombay Shoals. According to page 638 of John Pardos’ COMBINED FLEET DECODED, — as the the senior officer on the scene and knowing the possible prize — Capt Onada had crewmen from his escorting destroyers Hiyodori and Naganami board the abandoned USS Darter looking for documents the afternoon of 25 Oct 1944, after she grounded the night of 24-25 Oct 1944.

When the salvage crews of the US Navy arrived years later to finally destroy USS Darter by detonating her torpedo stock — which is mentioned in a report appended to the logs of the USS Darter — they found not a single classified document aboard.

|

| Figure 3: A 1944 aerial view of Mios Woendi and the Mios Woendi PT Boat Base (Camp Taylor) near Biak in New Guinea. Two Submarine tenders based here supported USS DACE and DARTER 27 – 29 Sept. 1944 with maintenance plus the latest secret communications, charts and other confidential documents prior to their engaging the Japanese Combined fleet off Palwan in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Photo Credit: Pacific Wrecks dot Org |

Page 53 (62)

“One of the most important discoveries of captured documents was made

by the Japanese Navy from the U.S. submarine Darter, which ran aground

west of Palawan on 23 October. The Japanese recovered many documents

dealing with radar, radio, and communications procedure, as well as

instruction books, engine blueprints, and various ordnance items.

It is difficult to evaluate the intelligence which the Japanese have

obtained from documents, but in those cases here it has been possible

the information has been found to be relatively accurate.“

Issues one through 15 would have been aboard USS Darter in October 1944. Taken together and analyzed by signals intelligence experts, they gave a complete technical background and a electronic listening fingerprint to all the major radio equipment used by the US Navy up to July 1944 including the YG Radio Homing Equipment used by US Navy strike aircraft returning to carriers. In short, Japanese signals intelligence had technical “Keys to the Kingdom” on every major piece of radio equipment in the American Navy. And this happened in time to be used for the Japanese Kamikaze Campaign no later than November 1944.

-Hold that Thought-

We will revisit it later.

A Confidential magazine published monthly by the

Chief of Naval Operations for the information of

commissioned, warrant, enlisted personal, and per ·

sons authorized, whose duties are connected with

the tactical use and operation of electronic equipment.THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS

PUBLICATION IS CONFIDENTIAL And as such

will not be transmitted or revealed. in any manner,

to unauthorized persons.

This Publication is to be handled in accordance

with Article 76 U.S. Navy Regulations, and will

be destroyed by burning when it has served its

purpose. Neither quarterly reports nor reports of

burning are required.

“This and other copies of “C,I.C” shall be included with other classified material which is to receive emergency destruction in the event of possible loss or capture. Commanding Officers of units employed in landing operations or similar hazardous duty are directed to destroy or land this publication prior to operations. C.I.C.” shall not be carried for use in aircraft.”

“Window” Pg 1 — The German & Japanese use of expendable radar decoys is discussed with radar scope photos.

“Radar and Weather” Pg 5 The effects of weather on USN Radars is discussed with diagrams of SK radar fade charts provided.

“This Is Fighter Direction” Pg 11“Fighter Direction Aboard an AGC” Pg 17

“Some Shipboard CIC’s” Pg 18 – Pages 11 through 20 are a series of photo essays showing fighter direction as executed with what equipment.

“The Night Fighter” Pg 21 – “…The care and feeding of” This article is about the training and maintaining of Night fighter pilot skills.

“Harbor Underwater Detection” Pg 24 — An article on allied harbor defense sensors, nets and organization of their use.

“Combat Lessons” Pg 26 — Includes “Leatherneck GCI” by VMF(N)-531, the USMC’s premier land based night fighter unit.

“Two Kills, One Probable” pg 28 — By Air Warning Squadron One (AWS-1) USMC’s premier land based radar unit and an USN ARGUS radar training group exercise where the “enemy” airplane hid in Santa Cruz’s radar shadow,

“Are You Sabotaging The IFF System?” Combat Information Center Sept 1944 Pg 1 – 6.

IOW, in a crowded sky, a lot of US planes, together, with their beacons turned on, could hide a Japanese plane trailing them because of the overwhelming number of IFF responses from a small area of a radar screen.

This was the exact tactic Japanese Kamikazes used off Luzon and Formosa against Task Force 38 (Adm Halsey) in November 1944.

The trick of following an enemy flight home to its carrier was new at Midway in June 1942.

But it was not until Dec 1944 almost 2.5 years later, a couple of months after the loss of the USS Darter, that Rear Adm Baker and Captain Thatch (of “Thatch weave” fame) invented the “Tomcat” picket destroyer concept. A tactic where there were two radar pickets, with overhead combat air patrol (CAP), either side of a line sixty mile towards the strike group’s target, were placed such that returning planes were to orbit them and be visually inspected for enemy planes by the CAP.

The US Navy advertised these as purely anti-Kamikaze defense** adaptations…but I’d scratch out the word “purely” and substitute “mostly.”

(** Per Adm McCain, on Page 58 of Adm. Samuel Elliot Morrison’s History of United States Naval Operations in WW2, Vol. XIII The Liberation of the Philippines.)

Author John Prodos also mentions the Darter capture in “The Combined Fleet Decoded”and states the Japanese got some useful information on US radar and diesel engines, but didn’t have the time or the resources to put them to good use.

The problem I have with “The Combined Fleet Decoded” assessment is the timing of the following kamikaze attacks —

Essex (CV 9), Philippines, 25 November 1944

Intrepid (CV 11), Philippines, 25 November 1944

Hancock (CV 19), Philippines, 25 November 1944

Cabot (CVL 28), Philippines, 25 November 1944

October 25, 1944 to late Nov 1944 is enough time for the Japanese to board Darter, get any non-burned papers, have a technical intelligence officer figure out the non-directional nature of the ABK & BN “ski-pole” Type 3 IFF antenna (Photos of the grounded USS Darter in 1945 show these intact above), and use that information to fox the USN fighter direction on Task Force 38 via following returning strikes close enough to get good IFF radar returns and strike those four carriers.

Then in reaction in Dec 1944, we have the US Navy develop “Tomcat” tactic of radar picket DD, with visual CAP inspection, introduced as mentioned by both Adm Morison in 1959 and again by Clark Reynolds in his 1968, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy,.

The repetitive mention by USN & USMC radar operators of IFF returns from Japanese aircraft during the Okinawa campaign certainly indicated that the Navy Department thought the Japanese had compromised the Type 3 IFF.

Yet you won’t find this fact in the narratives of the Okinawa campaign.

The full “Why” that was will await future columns in this series, but the then clearly inevitable post-war founding of the Defense Department had a lot to do with it.

-End-

Sources and Notes:

Combat Information Center Magazine on-line Archive

San Francisco Maritime National Park Association

Richard Pekelney, Webmaster

https://maritime.org/doc/cic/

Clark Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy, see page 290 for TOMCAT tactics, Originally published in 1968, currently published Naval Institute Press (March 5, 2008) ISBN-13: 978-1557507013, ISBN-10: 1557507015

Darter

http://hazegray.org/danfs/submar/ss227.htm

David Alan Johnson, “Darter & Dace at the Battle of Leyte Gulf” August 16, 2016

http://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/wwii/darter-dace-at-the-battle-of-leyte-gulf/

Mios Woendi PT Boat Base (Base 21, Camp Taylor) Papua Province Indonesia https://www.pacificwrecks.com/ships/ptboat/bases/mios_woendi/ https://www.pacificwrecks.com/ships/ptboat/bases/mios_woendi/1944/aerial-base21.html

Adm. Samuel Elliot Morrison, History of United States Naval Operations in WW2, Vol. XIII The Liberation of the Philippines, Little, Brown and Company; First Edition edition (1959)

NavSource Online: Submarine Photo Archive

Darter (SS-227)

Contributed by Lester Palifka

http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08227.htm

SRH-254 THE JAPANESE INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM MIS/WDGS 4 September 1945, page 53 (62 in PDF)

Electronic copy in author’s possession downloaded from the Proquest database at Nimitz Library Summer 2016

SS-227, USS DARTER Submarine War Patrol Report

Submarine aircraft carriers of Japan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarine_aircraft_carriers_of_Japan

USS Dace (SS-247)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Dace_(SS-247)#World_War_II

USS Darter (SS-227)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Darter_(SS-227)

Yamato-class battleships (大和型戦艦 Yamato-gata senkan)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamato-class_battleship

The torpedo problems of the early war showed how good the Navy was at covering up mistakes.

Joe Rochefort’s subsequent career showed how Navy politics worked.

Mike K,

The Level of US Navy prevarication involved in the Okinawa campaign reads like a 1949 Red Army history of the the invasion of the Soviet Union.

The US Navy’s operational security was an utter failure at the strategic, operational and tactical levels through out the Okinawa campaign and extended prior to then for the entire last year of the war.

The Japanese used this time and again and it is quite clear that some senior American military leaders were both aware of and took steps against it. The flag ranks that stands out in this regard are Admiral Halsey in the Central Pacific and General’s Kenney and Kruger under MacArthur.

None were involved with the planning of the Okinawa campaign.

Tangential: I read recently that throughout The War more than half of Japan’s soldiers were in China. Can that be true? Surely they would have tried to reinforce the home islands as the Americans got ever closer?

I can see that their troops in, for instance, Burma were too far away to bring home, but could they really not ship men home from China?

“but could they really not ship men home from China?”

The Japanese were starving because the blockade kept food from arriving. Why bring home more mouths to feed?

If they were so stuck that they couldn’t bring their troops home they should have surrendered. After the war their ruling cohort should have been executed for crimes against the Japanese people, never mind their crimes elsewhere in Asia.

Dearieme said —

>>Tangential: I read recently that throughout The War more than half of Japan’s soldiers were in China. Can that be true?

Yes it was. The Japanese used a significant portion of the Chinese economy to both support and arm that garrison. They could not have maintained the size of army they had without that Chinese loot.

>>If they were so stuck that they couldn’t bring their troops home they should have surrendered.

Japanese senior leadership was functionally insane, in that it was a “Face/shame” culture power group that made a horrible decision. They kept doubling down on that bad decision for internal power reasons until two nuclear attacks convinced them that “Doubling Down” was no longer possible.

Superbly done. A case study that should be required at the senior service schools.

Death6

Unbelievable. How many sailors were killed in those four kamikaze attacks because the stupid buffoons didn’t know how to classify their magazine?

Not only did the REMF staff writers drench their article with insufferable condescension, but the graphic is literally wagging its finger.

“Improved IFF performance will not result unless you demand that improvement.”

“These recommendations are not based on armchair braintrusting. A team of officers and civilians went to the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific areas to make a special study”

Oh really, thank goodness we had a brain trust to determine that the IFF will not operate without batteries nor if you fail to turn it on nor if you hold the antenna too close to your numb-skull. Meanwhile I guess silly tasks such as operational security that prevent thousands of lives lost will just be left to the unspecial teams.

Grurray,

There is a whole lot of American interservice politics in that September 1944 article you are unaware of. They will be in a future columns of this series.

For now, check out the March 1945 issue of CIC Magazine here:

https://maritime.org/doc/cic/cic-45-03.pdf

And read the IFF article at page 37. In particular pay attention to the first columns on page 41 (the South Pacific IFF Mission) and 42 (IFF being set off by Japanese Radar).

The South Pacific IFF Mission happened because local Japanese Navy pilots at Rabaul started shooting down our night bombers with a locally developed upward shooting cannon system which they developed for Japanese Navy Irving twin engine fighters. As a result of their efforts, one of the surviving USAAF bombers noted that at the same time it was being chased, that it’s IFF was being pinged as the Irving closed on it.

The local electronic warfare experts speculated in USAAF and Australian RAAF secret communications that the Japanese had captured an IFF transponder and was using it on a night fighter to chase our bombers.

What was actually happening was a ground based Japanese radar was in the IFF’s response band on the bomber’s set and was pinging at the same time as the Irving attacks by shearest coincidence.

Never the less, these speculations brought the wrath of Admiral King down on all concerned, because if the Type III IFF was compromised, do was US Navy Fleet Fighter Direction system.

The South Pacific IFF Mission found enough wrong with IFF use, particularly with Kenney’s 5th AF and the RAAF for reasons I laid out in my April 2014 column “Operation Chronicle and Airspace Control in the South West Pacific” (https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/42554.html) that the mission made villain of local pilots and their commanders for “Abusing and not maintaining” the Type III IFF equipment.

The “Wagging finger” of that column you read was aimed at General’s Kenney and MacArthur.

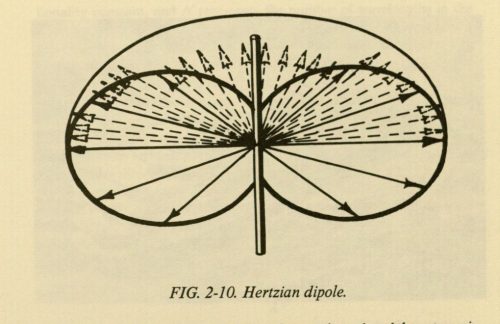

Numerous small edits, the numbering of the figures in the post and a diagram of a ABK/BN ‘Ski Pole type’ IFF antenna was added to the post for clarity.

Talking of “stupid buffoons”:

https://www.navytimes.com/breaking-news/2017/11/01/navy-crews-at-fault-in-fatal-collisions-investigations-find/

Dearie, there is a good summary here.

The failures seem to be a cascade, including overwork, poor training, excessive deployment with deferred maintenance and, possibly, incompetent officers.

It is amazing to me that simple rules of navigation were ignored. I know nothing about conning a ship but I have sailed thousands of miles and know that the most dangerous time of any trip is the approach of shore and traffic patterns. We would cross the Los Angeles ship traffic lanes on the way to Catalina Island and I know how fast ships move when you are in those confined waters.

Maybe electronic charts contribute. Paper charts give a picture that I’m not sure the electronic ones do as well.

I know the Navy is starting to teach celestial navigation again. Maybe they should go back to paper charts and plotting sheets. At least as backup.

I’ve no experience in a navy so I make only two points.

1 There are many references to Standing Orders. How big a collection of orders is that? Is it a huge book of cover-your-arse cases, or a terse book of “you really need to do this”?

2 In my experience you must practise doing the right thing again and again, and do the right thing even in circumstances where it seems trivially important or needlessly pedantic. Otherwise you’re unlikely to do the right thing when you are tired or stressed or hungry or fearful or soaked to the skin.

It’s possible to see the probable cost of this security breach, it only took 72 years and a lot of work. What is probably impossible to know is how many were saved because of the wide and rapid dissemination of this information. We’re no closer to being able to draw the line now then we were then.

Also note that the information was available to all ranks, down to the lowest that was interested enough to read it. This is rather at odds with a lot of popular military stereotypes.

Out of morbid curiosity, I’ve read a few marine accident reports. Several have found that the electronic chart and navigation systems were misused, often by zooming the displays to such a level that the bridge personnel couldn’t see shoals or other obstacles until it was too late. In the U.S. Navy, officers are generalists and rotated frequently between ships and shore assignments. This makes them dependent on senior ratings for detailed technical knowledge. This is in contrast to having separate deck and engineering tracks. The two exceptions are Submariners and Aviators.