This blog post on “Industrial Electrification and the Technological Illiteracy of the U.S. Army Air Tactical School 1920-1940” marks the new year with a departure from past history columns I’ve written for Chicagoboyz in that it is exploring a theme I refer to as “The Bane of Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders.”[1] As such, it will not be fully fleshed out with sources and notes. Consider it a ‘first draft’ of an article I’ll post later.

The issue with ‘Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders‘ I’ll be exploring in this and future articles is that such leaders tend to make the same classes of mistakes over and over again. And when those military leaders reach flag rank on the bones of theories and doctrines that fail the test of combat through their technological illiteracy. They then bury the real reasons why those doctrines failed behind walls of jargon and classification to avoid accountability for those failures.

Where you can see this pattern most easily in the historical record is with the US Army Air Corp Tactical School (ACTS) “Industrial Web” theory of strategic bombing and it’s inability to understand what the changes that industrial electrification caused had meant to this theory. The “Industrial Web” theory stated there were “choke points” in an industrial economy which bombing would cause a disproportionate reduction in enemy nation’s weapons production supporting total war.[2]

On the surface, this was a logical sounding intellectual construct. In practice, it failed miserably at places like the 14 October 1943 second Schweinfurt raid on German ball bearing factories and the Yawata Strike, the start of the early B-29 campaign on Japanese Coke ovens.

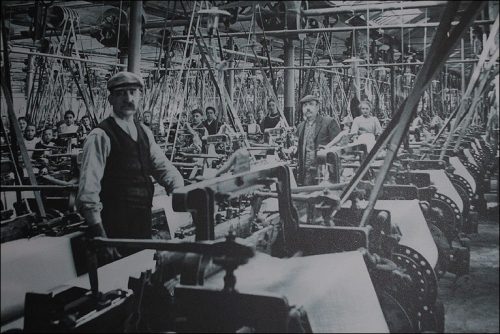

The unavoidable, in hindsight, issue for USAAF leaders trained in the Air Corps Tactical School in the period between 1920 and 1940 was that it spanned the change in industrial infrastructure from steam engine, line shaft and power belt to electric motor powered mass production.[3] Thus the ACTS theorists had a fundamentally flawed understanding of industrial economies vulnerability to aerial bombing going into World War 2 (WW2) because they were technologically illiterate regards the radical change industrial electrification caused.

This flawed understanding was that roof damage in a factory with line shaft and drive belt power transmission — whether steam or electric driven — stops all production until the roof-mounted line shaft is re-seated or replaced. This was not the case for electric motor delivered power located on the factory floor. The technological illiteracy here was not seeing the fact that electric motors fundamentally disassociated factory production processes from factory physical structure. [4]

The basic idea that ACTS theorists had at the time was that their “Industrial Web” was a serial system where every component had to work to produce an effect. Thus ACTS theorists fundamentally believed in the “weak link” theory of reliability, rather than the need to obliterate all key components that a parallel, or complex serial/parallel system, with redundancy required. The point failure weakness of line shaft and drive belt industrial infrastructure fit this “serial system with a weak link” belief system of ACTS theorists to a tee. [5]

So when you read wartime USAAF bomb damage assessment reports from the WW2 Combined Bombing Campaign giving such and such percentages of factory roof’s destroyed being used as a means of determining whether production there was knocked out. You are seeing a “weak link” short hand based upon line shaft power transmission infrastructure assumptions.

When you read later post-war bomb damage surveys reading “…that machines and machine tools were damaged far less severely than factory structures,” you are seeing a USAAF staffer dodging those pre-WW2 “Industrial Web/Weak Link” line shaft infrastructure assumptions by not using the term at all.

This sort of language shift to hide real world meanings with jargon, thus neatly avoiding accountability for failure in combat, is one of the classic ‘poker tells’ in researching ‘Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders‘.

WHAT INDUSTRIAL ELECTRIFICATION MEANT

There were vast productivity increases in new manufacturing plants built in the 1920’s based on the widespread availability of electric motors. And there were large ones in the conversion to electric power of existing manufacturing plants designed around steam-engine driven line shaft and belt power transmission. But it was the new manufacturing plants, designed with factory floor layouts optimized to use small electric powered motors, that were the most efficient.

When the Great Depression hit in America in 1929, the remaining steam-powered and mechanical line shaft driven industrial plants were quickly closed and never re-opened. The converted-to-electric-power mechanical line shaft plants were gradually closed and did not re-opened. All remaining American commercial production was then funneled through the newer, more efficient plants with layouts designed around electric power, and those simply did not need the manpower per unit of output that the closed plants, designed around steam power and line shafts did.

This meant that the industrial output of the late 1930’s could be provided solely with physical plant built in the 1920’s, but at far lower levels of employment. Furthermore, the 1930’s saw a vast amount of additional productivity increases as industry “tweaked” the factories built in the 1920’s based on experience with the then-new all-electric power layouts. This allowed still greater production from the same numbers of workers and electric power being used. [6]

When the US got involved in World War Two, industry mobilization in the 1940-1942 period — after factory conversion to armaments — just meant added more shifts to the 1920’s-built industrial plants as “tweaked” in the 1930’s.

ACTS MISSING THE INDUSTRIAL ELECTRIFICATION BOAT

Electrification of the major power economies in the run up to WW2 was an unrecognized “money solvable problem” for the “Industrial Web” theory of strategic bombing that happened at a time — the Great Depression — when there simply wasn’t the money.[7] There was no money to do the necessary international intelligence gathering on German or Japanese industry to identify “choke points.” And even if there was presidential support for money then — and there was not — the isolationist sentiment in Congress made any such funding request dead before arrival. Such was the American military’s 1920’s to 1930’s fear of budget cut political blow back from powerful and isolationist Midwestern Senators and representatives for suggesting such a thing.

The sole data set the ACTS theorists had available in the 1930’s was a very limited investigation by Air Corps officers of the industrial vulnerabilities of New York City. A city that had been industrialized during the 19th century steam age, from before the American Civil War of 1861-1865, and that had a line shaft and drive belt dominated industrial infrastructure reflecting it. New York City was one of the last places in America where industry fully converted to electric motor based mass production during the Great Depression due to the sunk investment in existing factories.

This funding shortage was further compounded by interwar institutional issues in the US Army Air Corps. Officers in the US Army Air Corps had to be rated pilots at some point in their career. There simply wasn’t the money for anything in the depression and thus there were very few planes and pilots. So the pool of Army Air Corps intellectual talent for good staff officers to even recognize the issue, let alone solve it, simply was not there going into WW2. The very best US Army Air Corps staff officers of that small talent pool were put on the staggering logistical job of expanding the Army Air Corps of tens of thousands in the period of 1940-1943 to an Army Air Force of _millions_.

There simply wasn’t the discretionary pool of Army Air Corps staff officer talent available to address electrification as applied to the “Industrial Web” theory and the search for “Choke Points.” This lack of talent meant very fundamental assumptions were never validated against real world data prior to repeated and bloody failures in combat.

Thus life and death decisions were made via logical constructions based on articles of doctrinal faith and selective picking of incomplete data, which replaced hard researched staff work. The time that should have been spent gathering and vetting data was instead put into glossy presentations, networking, and scholarly logical arguments based on accepted doctrinal ideas unvetted by real world data.

To be blunt about it, these 1940’s USAAF staffers were “Power Point Rangers” before the invention of Microsoft Power Point. This is another “poker tell’ behavior pattern to look for in researching ‘Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders‘.

Two examples of this WW2 lack of USAAF staff officer intellectual talent are the following:

1. The very shallow investigation of the American electrical power grid that took power plants off the aerial target lists after pre-war ACTS theory identified electricity as a “choke point,” and

2. The wartime identification of Japanese steel coking plants as a “choke point” done by USAAF Washington D.C. target planners.

The efficiency of America’s power grid had convinced USAAF target selection staffers that it was unprofitable to strike power plants. While at the same time the wide usefulness of steel convinced them that Japanese coal to purified carbon “Coking Plants” were profitable “Choke Point” targets.

The USAAF target planners didn’t think through questions like “What was the vulnerability of steam turbines and electrical generators to bomb blasts?” and “What was the lead time for steam turbines, multi-megawatt electric generators and high capacity electrical transformers?” because they didn’t see what it would buy them given the efficiency of the power grid.

This was bad staff work all around. If the USAAF target planners had asked those questions they would have discovered that this electrical capital equipment were very long lead items, on the order of a year to 18 months and that they were highly vulnerability to both bomb blasts and fragments. Either of those hitting large steam turbines and power generators having huge masses of metal moving at rotational velocities measured in terms of thousands of rotations per minute are very bad news. Furthermore, electric transformers generate a lot of heat when under load which required very vulnerable to bomb fragments liquid filled cooling blankets. The combination large steam turbines, power generators and large electrical transformers had a very distinctive visual signature that was easily seen by photo reconnaissance and bombers in good visual conditions.

If those power plant attacks had occurred. The regular striking of German power plants would have required the Germans to honor the threat of any approaching American bomber raid and shut down power generation plants regularly. This would have been done to protect the turbines and generators from blast damage that would cause fast moving rotating metal parts to “self-disassemble” like fragmentation bombs if aerial bomb blasts unseated the close tolerance rotating parts or fragments punched through the exterior jackets. And there was really no way to protect the massive transformers and their long haul electrical cables from bomb fragment damage that catastrophically severed power plants from their load.

The second order effects of unpredictable rolling brown outs and black outs on German industrial production, particularly high electrical energy aluminium smelting used to make aircraft engines and structure, can only be imagined. It certainly was not staffed out by WW2 USAAF target planners.

As far as the USAAF target planning focus on Coking plants for the XXth Bomber Command in China, CIA Author and former 14th Air Force Intelligence officer A.R. Northridge put it this way:

The realization on the part of the 14th USAAF staff that this magnificent new weapon with its enormous supporting base was being deployed a good two-thirds of the way around the globe to bomb coke ovens gave rise to wonderment — and argument. Each of us could think of targets by the score that were vulnerable to the B-29s and if attacked with vigor would save countless Chinese and American lives. To cite but one example, despite the slight pressure that the 14th Air Force could exert, slight because of our logistic transport difficulties, the Japanese had accumulated large stocks of materiel at Hankow. With this they had launched a drive that cost the 14th its eastern airfields and gave the Japanese an overland route between their Hong Kong-Canton enclave and their holdings on the middle Yangtze and the North China plain. Unequipped to offer serious resistance, the Chinese suffered personnel losses, military and civilian, numbering in the tens of thousands. The XXth Bomber Command could have destroyed the Hankow supply dumps in a single strike.

.

Or, again within easy range under a full bomb load, there was on Taiwan an operational air depot where new aircraft, fresh from the Japanese factories, were readied for combat and ferried off to the Philippines and the southwest Pacific to do battle with General Kenney’s air forces and Admiral Nimitz’ ships and the planes from his carriers. The destruction of this depot could well have shortened our approach to the Philippines and saved considerable losses in men, ships, and aircraft.

.

As the debate began to get acrimonious, the briefers left us. We spent the rest of the night studying their brochure and preparing an alternative plan for them to carry back to the JCS. We had not worked very long, plowing through the impressive presentation, before we could see that the conclusions reached were derived from elaborately contrived projections of equally elaborate hypotheses which were based, in the end, on meager data of dubious authenticity. This is an important point. The program was a scholarly piece of work, honestly researched and presented without gloss. The argument was logically flawless, but the authors simply lacked the basic data necessary to determine the proper use of the China-based B-29s. It became eminently plain that someone in Washington who had a fixation about the role of coke in Japan’s war economy had enlisted followers and somehow taken the JCS by storm. He must have been a very persuasive man.

.

It scarcely needs saying that the alternative program we prepared for the XXth Bomber Command was found wanting in Washington, and it was not long before the B-29s reached China under the original plan. [8]

GENERAL “HAP” ARNOLD TAKES A HAND

It was only through costly failure in war, and General Hap Arnold pulling in outside civilian academics for USAAF Operational Analysis, that the USAAF leaders and staff got even a limited understanding of industrial electrification during the Combined Bomber Offensive vis-Ã -vis fusing aerial bombs to explode between the roof a factory, where mechanical line shafts lived, and factory floor, where electrically powered machine tools lived. And that bombs had to explode between the two, as the Germans put up blast and fragment abatement walls inside their electrified factories. [9]

USSBS LESSONS LEARNED AND HIDDEN

In the aftermath of the end of the war in Northwest Europe, the UK and the USA conducted a serious evaluation of the effects of strategic bombing. The American investigation was called the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS). This effort was the brain child of former ACTS instructor and now Maj. Gen. Muir S. “Santy” Fairchild. It was a wide ranging effort to document the American portion of the Combined Bomber Offensive. It had 212 reports and the summary report for the European air campaign declared, “Allied airpower was decisive in the war in Western Europe.”

This is what the USSBS summary report for Europe said regards targeting electrical power in the war against Germany.

Electric Power

.

The German power system, except for isolated raids, was never a target during the air war. An attack was extensively debated during the course of the war. It was not undertaken partly because it was believed that the German power grid was highly developed and that losses in one area could be compensated by switching power from another. This assumption, detailed investigation by the Survey has established, was incorrect.

.

The German electric power situation was in fact in a precarious condition from the beginning of the war and became more precarious as the war progressed; this fact is confirmed by statements of a large number of German officials, by confidential memoranda of the National Load Dispatcher, and secret minutes of the Central Planning Committee. Fears that their extreme vulnerability would be discovered were fully discussed in these minutes.

.

The destruction of five large generating stations in Germany would have caused a capacity loss of 1.8 million kw. or 8 percent of the total capacity, both public and private. The destruction of 45 plants of 100,000 kw. or larger would have caused a loss of about 8,000,000 kw. or almost 40 percent, and the destruction of a total of 95 plants of 50,000 kw. or larger would have eliminated over one-half of the entire generating capacity of the country. The shortage was sufficiently critical so that any considerable loss of output would have directly affected essential war production, and the destruction of any substantial amount would have had serious results.

.

Generating and distributing facilities were relatively vulnerable and their recuperation was difficult and time consuming. Had electric generating plants and substations been made primary targets as soon as they could have been brought within range of Allied attacks, the evidence indicates that their destruction would have had serious effects on Germany’s war production.

While the USSBS in the passage above underlined that the USAAF failed to strike electric power during WW2 that was identified as a “choke point” vulnerability per its pre-war “Industrial Web” theory. [10] What it didn’t do was document in one place what that lack of understanding of industrial electrification meant for the strategic bombing campaign. And specifically how that lack related to the fundamental assumptions of the Industrial Web theory of strategic bombing. Other than the USSBS summary reports of the European and Pacific, most of the evidence gathered via wartime operational research and in the USSBS — which showed how often the “Choke Point/Weak Link” part of the “Industrial Web” theory didn’t pass the test of combat — was classified until after the end of the Cold War.

It wasn’t what pre-war USAAF leaders didn’t know that got many of the 26,000 airmen and pilots killed in the strategic bombing campaign in Europe in World War 2 — more than died in the US Marine Corps from all causes!

It was what the ACTS instructors and students thought they knew about industry, which wasn’t true — because of the industrial electrification revolution — that got many of those men killed.

And, as the declassified CIA report authored by A.R. Northridge shows, those military leaders used the classification system to hide their responsibility for this failure of “Industrial Web” theory.[11] It is this use & abuse of the classification system that is the common denominator regards “The Bane of Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders.”

-END-

Notes and Comments

[1] The genesis of this ‘Technologically Illiterate Military Leaders’ writing theme is my watching the Department of Defense wrestle with the emerging industrial revolution of 3D printing/additive manufacturing. And in particular, watching the pronouncements of senior US military leaders about how their services will be producing parts for themselves. These pronouncements show an appalling ignorance of issues of ownership of technical data for the parts and what amounts to technological illiteracy on issues of industrial quality control in military organizations that have between 20% and 40% personnel turn over a year.

As most of the 3D Printing/Additive Manufacturing TED talk gurus and consultants are using the electrification of the American economy from 1920 thru 1940 as their baseline comparison. This is where I’m starting.

[2] The term “Industrial web theory” was never in any US Army Air Corps doctrinal publication. This term was coined in the 1930s by Donald Wilson, an instructor at ACTS, to cover strategic bombing concepts then under development. See Wikipedia link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_web_theory

[3] Line Shaft and Drive Belt Technology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Line_shaft

[4] This failure was not limited to just the American Army Air Force. The UK Air Ministry, senior Royal Air Force leaders, the UK’s wartime Ministry of Economic Warfare, and most importantly RAF Bomber Command were equally ignorant and illiterate regards the disassociation of factory processes from factory structure in industrial society that electrification wrought at the start of WW2. For issues of RAF Bomber Command’s WW2 intelligence, see RAF Wing Commander John Stubbington’s “Bomber Command: Kept in the Dark” Pen and Sword (June 19, 2010) ISBN-10: 9781848841833, ISBN-13: 978-1848841833.

It is unclear if the very poor German Luftwaffe intelligence arm ever considered the issue of industrial electrification at all. This lack would hurt them after Operation Barbarossa, when evacuated electrical motor based production equipment lead to the industrial recovery of the Soviet Union’s armament industry in 1942-1943.

[5] For understanding the “weak link” versus more robust approaches to reliability, see J. DeVale (1998). “Basics of Traditional Reliability”

http://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/des_s99/traditional_reliability/presentation.pdf

[6] Robert Higgs “Depression, War, and Cold War: Challenging the Myths of Conflict and Prosperity” (Independent Studies in Political Economy), Independent Institute; 1st Printing edition (May 1, 2009), ISBN-10: 1598130293, ISBN-13: 978-1598130294. Higgs’ book is very useful because it includes a careful analysis of economic productivity factors of electrification underpinning the American economy in the 1920 – 1945 period.

[7] “History of the Air Corps Tactical School, 1920-1940” Research Studies Institute, USAF Historical Division, Air University, 1955. (USAF historical studies; no. 100). www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a432954.pdf It’s telling that when you search inside the Adobe PDF version of this history that the word “electric” appears three times (pages 27, 65 and 75), with the first time referring to powering the base where ACTS was housed. While the terms “line shaft” and “drive belt” do not appear at all.

[8] A.R. Northridge suffered a “Death by Power Point” briefing decades before it was invented by Microsoft. He did far better in his complaints than did fired US Army reserve Colonel Lawrence Sellin in 2010 for a similar rant. For what it is worth, the Okayama air depot on Formosa (now Taiwan) mentioned by A.R. Northridge was struck by the B-29’s of XXth Bomber Command using then secret radar proximity bomb fuses the night of October 13-14, 1944 as a part of the preparation for the Leyte Campaign. See pages 137-138 of W.F. Craven & J.L. Crate’s Volume V of The Army Air Force in WW2 “The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945” and page 423 of SUMMARY TECHNICAL REPORT OF DIVISION 4, NDRC, VOLUME 1, RADIO FOR PROXIMITY FUZES FIN-STABILIZED MISSILES, WASHINGTON, D. C., 1946

[9] Charles W. McArthur “Operations Analysis in the United States Army Eighth Air Force in World War II,” American Mathematical Society, London Mathematical Society; 1st edition (January 7, 1991) ISBN-10: 0821801589, ISBN-13: 978-0821801581. See in particular the various bomb fuse sub-sections through out his fine work.

[10] As then USAAF Maj Gen. Fairchild was the ACTS instructor advocating hitting electrical power as a USAAC major in 1939. This passage was certain to be in the USSBS, if the data supported it. See page 75 in note [7] above.

[11] A.R. Northridge, “B-29s Against Coke Ovens,” APPROVED FOR RELEASE, CIA HISTORICAL REVIEW PROGRAM, 22 SEPT 93, https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol9no3/html/v09i3a05p_0001.htm Please carefully note the Post-Cold War _1993_ declassification date. Having your “Power Point Ranger before there was Power Point” rant about poor USAAF WW2 staff work by officers who likely went on to flag rank in the USAF classified for 49 years _in the CIA_ sure helps your career as an intelligence officer.

Very interesting. Something like this occurred with military small arms.

I read this book years ago.

It points out that repeating rifles with cartridge magazines could have ended the Civil War early with far fewer casualties. The Confederacy did import repeating rifles from Europe but never enough and they had no industrial capacity to make the metal cartridges. The Confederates often armed themselves with captured muzzle loading muskets. The Minie’ ball made rifled muskets far more accurate but the musket still used black powder that was easily made in the south. Had the federal Army used Henry or Spencer repeating rifles, capturing them on the battlefield would not have been of much value since the ammunition required technology the Confederacy did not have.

Then, of course, the US Army refused to use the BAR in Europe in WWI for fear the Germans would capture one and copy it. The Germans had better machine guns, especially the Maxim gun, and the US used the inferior Chauchat light machine gun.

The muddy trenches of northern France exposed a number of weaknesses in the Chauchat’s design. Construction had been simplified to facilitate mass production, resulting in low quality of many metal parts. The magazines in particular were the cause of about 75% of the stoppages or cessations of fire; they were made of thin metal and open on one side, allowing for the entry of mud and dust. The weapon also ceased to function when overheated, the barrel sleeve remaining in the retracted position until the gun had cooled off.

The book above also explains why the M 16s were jamming in Vietnam. The Army changed the specs for the powder and did not issue cleaning kits. The original AR 15 powder did not foul barrels and actions. The Army powder did.

Very interesting post.

One of the lessons of life is that we can do almost anything better the second time around; but we have to take decisions based on what we know at the time, without the benefit of later hindsight. Yes, there could certainly have been better choices of targets for bombing — but it is at least arguable that the main problem was the very poor accuracy of bombing under the best of conditions. And with frequent heavy cloud cover and active efforts by those being bombed to make life dangerous for the bomb crews, the best of conditions were very rare. Just in casual reading about WWII, it is not uncommon to see references to bombs missing the target by literally miles.

Electric generating plants may not have been a focus of WWII bombing, but oil refineries and related installations were. While frequent bombing of those oil-related plants certainly caused damage and reduced output, it did not shut them down; probably in part because of the bombing accuracy problem.

It was the failure of bombing industrial installations which led all sides to switch to area bombing — make like miserable for the workers and demoralize the ones who were not killed. And yet that strategy did not work too well either. The civilian populations of neither Britain nor Germany nor Japan cracked under the assault of bombers. There is a telling scene in the movie “Fury” in which the tank crew are looking at distant smoke from burning German cities as still more flights of Allied bombers fly overhead. One of the tank crew asks ‘Why don’t the Germans just give up?’. And the tank commander responds ‘Would you?’.

One thought was that water/steam based factories were often dispersed to be close to rivers/coal mines. Here in New England they were everywhere and were mostly factory towns. Newer factories were located in Cities to be close to reliable electric power and workers. So the area bombing tactics were also pretty good at distrusting industry. The idea of a choke point like a key battle is often a dream to have a cheap, quick victory. Len Deighton’s book ‘BLITZKREIG” has interesting discussions on the limitations of German defense industries in the late 1930’s and how Czech and French factories filled the gaps during occupation.

The two most important things to remember about the European strategic bombing campaign in WW2 was, first, that 80% of all bomb tonnage dropped on Germany fell between June 6th 1944 and German surrender in May 1945.

Second, it took a whole lot of “Learning by Dying” to the tune of 66,000 RAF Bomber Command and 26,000 8th and 15th Air Force bomber crew to win the European Strategic bombing campaign.

A better choice of targets before D-Day — specifically the Ruhr’s electrical power plants — would have reduced the butcher’s bill to the tune of several thousand lives.

A 10% reduction in the human cost of the European strategic bombing campaign meant 9,200 lives saved.

the limitations of German defense industries in the late 1930’s and how Czech and French factories filled the gaps during occupation.

Another reason Chamberlain was so wrong to give away that armaments industry at Munich. There was always the issue of the loyalty of the Sudeten Germans but I don’t know enough about the location of the Czech munitions plants.

I hate to say that this was inexcusable, but it was. For the cost of some trade magazine subscriptions and a few trips around to places like Detroit and attending trade shows and SME conventions, the army people could have figured out what was going in. There was a lot, and I do mean a lot of literature and correspondence course going around with pictures of new factories like the automobile industry demonstrating that the lineshaft was on the way out. A few machine tool catalogs, even German ones, would have gone a long way. I suspect that the Rock Island arsenal could have shown them all the latest tenchiques. But they had this idea and visited all the wrong factories in New York. Is there a report on just what they did visit?

New York City was one of the last places in America where industry fully converted to electric motor based mass production during the Great Depression due to the sunk investment in existing factories.

I was reading something recently about Edison’s efforts to set up electricity in New York City. He was faced with bitter opposition not only from the established gas companies but also citizens who were so used to using gas. He decided to make the transition as seamless as possible by making the change evolutionary instead of revolutionary. He ran the power lines through existing gas lines in the ground even though it was less efficient than overhead lines and would prove to be an impediment to later adopting AC current. Edison also convinced people that new electric lamps would just easily fit onto existing gas chandeliers and fixtures that had been ubiquitous in buildings and homes for decades. He was careful to keep the light dimmer than it could have been in order to mimic the light from gas lamps.

So maybe sunk investments can be some part of the problem, but I don’t think a sunk investment is always a problem. There is often a valid reason why we sink so much into an idea, and that is because there is a meaning and value beyond the obvious surface appearances.

Ironically, the real problem of the experts not venturing out to see how the latest technology performs shouldn’t be pinned on the Midwestern isolationists (I prefer to call them non-interventionists, by the way, but whatever). The experts should’ve gone out to talk to some of those Midwestern isolationists to find out how they re-tooled during the Depressiom. After bit of critical thinking they may have realized that was what the Germans were doing too, but I suppoe that may be too much to expect from experts.

My parents home in Chicago was built in 1912 and had gas fixtures in the living room and bathroom.

I guess they were doing as belt and suspenders thing.

There was a book published in 2016, of which I read in AIR & SPACE Smithsonian about the bombing campaign (and bought the book). The bomber crews didn’t know what they didn’t know, and I suspect the bomb groups’ intel officers didn’t either. I read that the Norden bombsight came to be used only by the lead aircraft’s bombadier, and all the crews following him dropped their bombs upon seeing him drop his bombs. So, mostly not aimed at targets.

Jccarlton

>> Is there a report on just what they did visit?

Yes, but nothing detailed like was in the USSBS or the UK evaluations of German bombing 1939-1941.

There was no money, remember.

Among other things the ACTS instructors did an aerial survey of NY City looking for “choke points” from the air.

One of the photos in the survey is of the port of New York showing all the railways from the piers necking down to a single double track line with a caption to the effect “This looks like a choke point to me.”

Running down that limited ACTS NYC data set versus the UK bomb data and the various wartime bomb data and USSBS data sets is what the bigger article needs and I didn’t have time for at the moment.

Grurray

>>So maybe sunk investments can be some part of the problem, but I don’t think a sunk investment is always a problem. There is often a valid reason why we sink so much into an idea, and that is because there is a meaning and value beyond the obvious surface appearances.

Sunk investments were very much a problem for the European Strategic bombing campaign because many of the British “Shadow Factories” were subsidized “converted to electric power line shaft and drive belt” facilities.

Thus the data the UK gathered on German bombing of UK industry 1939-1941 reflected the older line shaft and drive belt factories that the British government subsidized in the 1930’s and not the newer electric motor powered armament factories the Germans built under Hitler.

I don’t know how many have read “Once an Eagle” by Anton Myrer but it includes an episode where an army officer takes his family on a vacation in the 1920s and spend the time working for a relative of his wife’s. He uses his own skills as a logistics expert to reorganize the relative’s plant.

It might have been a good thing for some of the officers who were planning the next war to have spent some time in real factories and seen what was developing.

The publication of the “Rainbow Five plan” in newspapers was probably done by the Air Corps, which felt very unprepared.

In 1963 Frank C. Waldrop published an article recalling his memories of the big leak. He told of having lunch after the war with the FBI man who had directed the investigation. The agent told him the bureau had solved the case within ten days. The guilty party was “a general of high renown and invaluable importance to the war.” His motive was to reveal the plan’s “deficiencies in regard to air power.”

In a recent interview Waldrop added some significant details to this story. The FBI man was Louis B. Nichols, an assistant director of the bureau. Waldrop asked him, “Damn it, Lou, why didn’t you come after us?” Waldrop and everyone else at the Times Herald and the Tribune had hoped that the government would prosecute. They had a lot of information about the way the White House was tapping their telephones and planting informants in their newsrooms that they wanted to get on the record. Nichols replied, “When we got to Arnold, we quit.”

It was probably Hap Arnold, although Wedemeyer was suspected at the time.

One of the photos in the survey is of the port of New York showing all the railways from the piers necking down to a single double track line with a caption to the effect “This looks like a choke point to me.”

I’ve been listening to Victor Davis Hanson on WWII quite a bit the last couple of weeks. I remember him making the point that Allied bombardment of German railways was largely ineffective at first because it was focused on the rail lines themselves. They are obviously small targets and difficult to hit, but also relatively easy to repair or find bypasses around the damage. They finally figured out they needed to start hitting marshaling yards which are bigger targets, far more difficult to repair, and can’t be worked around.

Christopher B.

VDH was referring to a book by the author Alfred Mierzejewski on the role of the Reichsbahn AKA German railways in WW2. Searching with the author’s name will get you his book on amazon.com.

The book relies entirely on German Railway documents in the German archives and it is absolutely vital in understanding how the Allied strategic bombing campaign destroyed the German economy.

The effect of a multi-hundred heavy bomber strike on a Reichsbahn railway marshaling yard was roughly equivalent to mining a sea port. Like ships on both sides of a mine field, massive bombing strands many dozens of engines and thousands of rail cars until the damage is repaired.

For a lot of reasons amounting to bureaucratic factional politics of the worse sort, the Allies didn’t systematically strike every major nodal railway marshaling yard simultaneously and keep striking them to stay ahead of the repair crews until early March 1945 in a campaign that lasted for six weeks.

It’s huge success in causing the German economy to collapse is not talked about because one of the railway marshaling yards struck in this campaign was in a city called Dresden.

Christopher B.

This is the book I referred to:

The Collapse of the German War Economy, 1944-1945: Allied Air Power and the German National Railway

by Alfred C. Mierzejewski

And Amazon.com reports he has a 2nd edition in kindle format for ~$18 —

The Most Valuable Asset of the Reich: A History of the German National Railway Volume 2, 1933-1945

Trent, I was hoping that the study was online so that I could do a blog post looking at what the ‘experts’ saw vs what I know about NYC, a topic of interest of mine for a long time. If they thought that closing a single rail line was going to shut down New York, they would have been rather shocked. Back in the 1930’s most of New York’s intercity and import freight moved on water to the piers. You would have to sink literally thousands of car floats to achieve that. To say nothing of lighters and covered barges.

As for the aerial survey, did the Air corps waste their money and do it themselves or did they use the Fairchild survey that the city commissioned in the 1920’s.

Jccarlton,

See page 17 of this graduate paper on-line

THE UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY

AND AIR FORCE DOCTRINE

BY

JOHN K. MCMULLEN

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.191.74&rep=rep1&type=pdf

This is a passage from that page which gives the ACTS lectures they are drawn from —

“As an intellectual tool, ACTS used New York City as a model to further develop their ideas concerning the vital links in an industrial chain. Transportation, electrical power, raw materials and water were all among the vital links that, if targeted, would bring down the New York industrial and economic systems.16 The information for the analysis of New York City was readily available, but would intelligence be able to provide the required information against a potential enemy? ACTS believed that it would as cited in the following quote from an ACTS lecture:

I hope [that it] is apparent to you, that all the necessary information to make the required analysis is available in time of peace””available to all the world. Proper analysis of that information will give us a very definite answer as to the degree of vulnerability and the effect to be anticipated from the various degrees of destruction.”

Point in fact, come the day, there was no such information available.

Jccarlton,

Also see this book:

The Foundations of US Air Doctrine – Air University

https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/AUPress/Books/B_0008_WATTS_FOUNDATIONS_DOCTRINE.pdf

And particularly this chapter —

FIRST US STRATEGIC AIR WARPLAN

pages 19 and 23

“In spite of the analytic challenges embodied by these questions, the AWPD-1 planning team ultimately settled on four basic target systems totaling 154 individual targets:

(1) Electric power (50 generating plants and switching stations) .

(2) Transportation (47 marshaling yards, bridges, and locks) .

(3) Synthetic petroleum production (27 plants) .

(4) The Luftwaffe, especially its fighter arm (18 airplane assembly plants, 6 aluminum plants, and 6 magnesium plants).17

The last of these four systems, the German air force, was described as an

“intermediate objective of overriding importance” on the grounds that German fighter defenses would have to be overcome for the strategic air offensive to be effective .”The other three systems-electric power, transportation, and synthetic oil-were designated “Primary Objectives,” meaning that in the opinion of the team, they constituted those vital links whose destruction or neutralization would mean that Germany’s entire economy would cease to function. To achieve this end, the planners assumed the full bomber force (over 3,800 mediums and heavies) would be devoted exclusively to attacking the complete AWPD-1 target list for a period of six months. 19”

By way of comparison to that Hansell list, the 15th Air Force struck _50_ transportation targets in Germany in the Feb 1945 for Operation Clarion.

The 8th AF hit another 42. For which, see —

Narrative – Official Air Force Mission Description

Mission 841:

http://www.8thafhs.com/get_one_mission.php?mission_id=1853

1,428 bombers and 862 fighters commence Operation CLARION, a joint RAF, Eighth, Ninth and Fifteenth AF operation with the objective of paralyzing the already decimated German rail and road system; most attacks were made visually; bombing was conducted from an optimum 10,000 feet (3,048 m) to achieve accuracy at target without flak defenses; they claim 28-2-43 Luftwaffe aircraft; 7 bombers and 13 fighters are lost:

1. 522 B-17s are sent to hit marshaling yards at Bamberg (64), Zwickau (2) and Kitzingen (1); targets of opportunity are Ansbach (143), Donaueschingen (24), Reutlingen (25), Ulm (77), Freiburg (21), Hafingen (10), the marshaling yards at Aalen (24), Neustadt (26), Singen (8), Schwenningen (22), and Villgen (11) and other (42); some attacks are made with H2X radar; they claim 0-0-1 aircraft; 2 B-17s are lost and 29 damaged; 2 airmen are WIA and 19 MIA. Escorting are 163 of 168 P-51s; 3 are lost (pilots MIA).

2. 452 B-24s are dispatched to hit marshaling yards at Halberstadt (51), Sangerhausen (11), Nordhausen (30), Vienenburg (23), Peine (52), Hildesheim (55), Kreiensen (48), and Northeim (48); targets of opportunity are Nordhausen (11), Ottbergen (10), the rail and highway bridge at Lindern (1) and marshaling yards at Wallhausen (19), Oker (8), Eschwege (30), Gottingen (29) and Celle (8) and other (1); 4 B-24s are lost and 68 damaged; 2 airmen are WIA and 38 MIA. 246 P-47s and P-51s escort; they claim 19-0-16 aircraft on the ground; 4 P-51s are lost (pilots MIA).

3. 454 B-17s are sent to hit Wittenburg (72), Stendal (73), Salzwedel (59), Uelzen (73), Wittstock (11), Luneburg (39), and Ludwigslust (48); targets of opportunity are Grabow (13), Kobbelitz (24), Dannenberg (12) and Klotze (13). The escort is 268 of 280 P-51s; they claim 4-2-18 aircraft in the air and 3-0-5 on the ground; 5 P-51s are lost (pilots MIA).

4. 99 of 103 P-51s fly a freelance mission in support of the bombers; they claim 2-0-0 aircraft in the air; 1 P-51 is lost (pilot MIA).

5. 28 of 32 P-51s fly a scouting mission; they claim 2-0-3 aircraft on the ground.

6. 13 P-51s escort 10 F-5s and 5 Spitfires on photo reconnaissance missions over Germany.

Trent T: “It’s huge success in causing the German economy to collapse ”¦”

Did the German economy collapse? The place was a mess, for sure, but the damage to the economy did not stop the fighting. The Russians had over-run eastern Germany and taken Berlin (against strong opposition), the Western Allies had over-run most of western Germany, Hitler was dead ”¦ and still the fighting dragged on. Shades of the Pass of Thermopylae!

Some have argued that the difficulty of bringing the European war to an end was part of the thinking behind the use of nuclear weapons in Japan, to persuade the Japanese to surrender while there still was some kind of functioning authority that could get the Japanese people to lay down their arms.

The interesting aspect of all this is the moral issue of the switch from the World War I view of War being between armies to the World War II Total War approach of treating the entire enemy citizenry as viable targets. Perhaps that difficult moral issue arose only as a consequence of the inability to bomb any target with precision? Your research into this area will be very interesting.

Gavin Longmuir,

The Reichsbahn lost all ability to track it’s engines and cars when the final 6-week aerial transportation offensive against it’s major marshaling yards kicked off the first week of March 1945 and at the end — mid-April 1945 — it could not even transport enough coal to power its own trains.

This is in Mierzejewski’s “The Most Valuable Asset of the Reich: A History of the German National Railway Volume 2, 1933-1945.”

Actually the Army Air Corps/Force DID know about the electric power motors running German factories. Some bombardment guy from the Air Corps Tactical School had the great idea of checking with the US banks which financed the German factories built in the 1920’s and 1930’s for details of the factories’ construction.

And those banks still had the German business proposals for how they would use the bank loans. Including factory floor plans.

The Air Force’s bombardment guys used that information in making targeting decisions during World War Two.

It just didn’t occur to them that the use of electric motors for powering equipment made their plans for wrecking the factory roofs to destroy the power distribution systems completely irrelevant. They had the information and didn’t connect the dots.

I’ll leave it to Trent to explain why they didn’t understand the implications of they had cleverly obtained.

Trent: “… it could not even transport enough coal to power its own trains.”

We may be ships passing in the night on this. Yes, Allied bombing campaigns disrupted Germany’s supply chains — especially late in the war, when the cumulative disruptions to fuel supply rendered the Luftwaffe impotent and made it easier for Allied bombs actually to land on the intended target. All I was trying to suggest is that those disruptions did not stop the fighting — did not stop the war.

You may remember the scene from the movie “Patton” where General Patton is so impressed with one of his wounded soldiers — their tanks ran out of fuel, they ran out of ammunition, and they continued to fight the Germans hand-to-hand. There is more to winning a war than choosing the right target to bomb.

I have an interesting book about the last battle of the war, when US and German soldiers fought together to save the French political prisoners from the Nazis.

It’s called “The Last Battle” and is not the Cornelius Ryan book.

One of the problems you run into with the military is that there isn’t a whole lot of imagination in the supervisory ranks, and what little there is winds up sidelined, much of the time.

This is why “nobody saw” so many things, like the effect of machine guns, barbed wire, and artillery in WWI, and why we were “surprised” by the IED campaign in 2003 that nearly crippled us in Iraq. All of that “stuff” was foreseen, and by numerous parties within the military structures that missed it. Where the problem lay was in the system and hierarchy itself–There was nothing to be lost by continuing to bet on the primacy of conventional military operations before WWI, and so, the men forecasting the impact of the machine gun and so forth were seen as risky bets by those who made the decisions.

Had the French taken the tools and techniques that they took to WWI into the Franco-Prussian War, things would probably have worked out better for France; unfortunately, the moving finger of technology and technique had moved on, and their ideas of how to fight had become obsolete and ineffective.

The other problem is the one we had with regards to the IED campaign; the problem existed at the seam of things, being neither truly tactical nor truly logistical. There was no clear doctrinal owner; that form of warfare by denial and attrition was not purely owned by either the maneuver forces or the rear-area logistics people. The Engineer Branch should properly have taken it up, but the Engineers are a service branch; if nobody asks for or demands that the task/mission be done, they’re not going to bother gearing up to do it–And, the bureaucracy is going to actively seek avoidance of that sort of thing, because it does not want to spend what little money it already has on new things like MRAP and armored route clearance vehicles.

Part of the problem, to my mind, is the inherent inflexibility of the hierarchy and system that we use to approach everything; instead of saying to a group of generalists “Hey, we want you to be ready to wage war as it is fought today…”, what we do is break it down into different branches who each have their own parochial interests and approaches to the question of what is important in war; this is a recipe for rigid maladaptive performance. We badly need to rework our paradigm for how we go about doing these things, which seems to always include throwing up a new bureaucratic structure that takes on a life of its own, and then starts seeking out new justifications for its existence, rather than dissolving once the problem is solved.

Hierarchy and rigid bureaucratic structure is not something we humans are necessarily good at–Every one of these things we’ve thrown up, over the centuries, has turned into self-aggrandizing structures that are more concerned with self-perpetuation than dealing with the original problems. It’s like the various charities set up to fight things like polio and other long-gone childhood diseases: Did any of them say “Our job is done; we can shut down, now…”? Oh, hell no–They went out looking for new windmills to tilt at, just like so many bureaucratic Don Quixotes.

We very badly need to come up with better ways of doing these things, and erasing this impulse towards hierarchical bureaucracy as a solution to every problem. The mess we create doing this crap is why things like WWI and the IED campaign even happen; had we had a more flexible and adaptable structure, the people who saw the light of the oncoming IED train would have been listened to, preparations made, and precautions taken. As it was, we had to wait until the train wreck happened.

I’m tired of train wrecks.

We badly need to rework our paradigm for how we go about doing these things, which seems to always include throwing up a new bureaucratic structure that takes on a life of its own, and then starts seeking out new justifications for its existence, rather than dissolving once the problem is solved.

Read “Jawbreaker” about the initial Afghanistan war. The CIA and Special Forces had organized a good campaign with Afghan fighters.

Then The “Big Army” arrived and told the SF guys to “shave and get into uniform.” After that the mini-empires were built.

Dakota Meyer tells the story in his book about how long it took to get artillery to respond when his small unit was ambushed. It was hours.

“someone in Washington who had a fixation about the role of coke in Japan’s war economy”…

Has this someone ever been identified? It reminds me of the malign influence of Ancel Keys on nutrition.

On a related topic: I saw an article a few years ago on how failures in armed service operational procedures and doctrines were discovered in the field, where fixes were put into service. Then at the end of the war, the field organizations which had implemented the fixes were demobilized. But those fixes often had never been incorporated into the official manuals, so a later generation of users had to discover them again.

This is a meta-failure, which continues to this day.

Gavin Longmuir

>>There is more to winning a war than choosing the right target to bomb.

Oh, absolutely!

Airpower has always over promised and under performed.

The first step in Alcoholic’s Anonymous is the admission that there is a problem.

The issue I’m trying to address here is that American military leaders of the era were really bloody ignorant and technologically illiterate with the bombs they did drop.

The B-17 was designed in the early 1930’s to deliver a 500-lb bomb designed to the specifications of the USAAC to blow a hole in the roof of a line-shaft and drive belt factory.

The B-17 carried 12 of them. So did the B-24, to a longer range.

The medium bombers B-25 and B-26 up to six 500-lb bombs.

The B-29 carried 40 each 500-lb bombs.

The issue is this entire suite of planes I just called out were designed around a munition that was made obsolete by advancing electric motor production technology 10 years before they were used in war.

The parallel’s here with the F-35’s suite of air to air and air to ground munitions here are extremely uncomfortable.

a later generation of users had to discover them again.

A friend of mine was an Army pathologist in the Korean War. They encountered Korean Hemorrhagic Fever, which is a viral fever transmitted from rats.

It was a new disease and the Army knew nothing about it. Lots of fatal cases were encountered.

After the war, he learned that the Japanese had studied the disease in the 1930s and 40s, sometimes using POWs as subjects for experiment. The Japanese records were sealed as all evidence of Japanese war crimes was suppressed by MacArthur after the Second World War. We had to learn about it from scratch.

“The first step in Alcoholic’s Anonymous is the admission that there is a problem.”

Absolutely! No disagreement with your thesis that the bombs could have been better designed. But even perfectly designed bombs would not have achieved the objective when so many of them were missing the targets. And even poorly designed bombs might have been adequate to the task if more of them had landed on the intended target.

There were at least two problems with bombing campaigns — the design of the bombs, and the very poor bombing accuracy (especially when bombs had to be dropped in a “non-permissive” environment of intense opposition by those being bombed).

The military serves the nation — functionally, the Political Class. In matters of organization, the ultimate blame for the failure of the military to plan properly has to be laid at the feet of the people who control the military, ie the politicians.

Trent — I am a mere dilettante on these kinds of matter; I have great respect for your deep dives into the source materials, and sincere interest in what you uncover. As a dilettante, let me pass on an example of the kind of snippet that leads me to suspect that bombing accuracy (really, inaccuracy) was the key factor in the Allies morally-challenging decision in both the European and Japanese theaters to switch from targeting industrial facilities & infrastructure to burning down cities & their inhabitants.

This is from Robert Buderi’s book about the impact of the development of radar and associated technologies, “The Invention That Changed The World”. In his Epilogue, Buderi points to the successes of Desert Storm as an example of how radar (and radar-avoidance technologies) have transformed the military. Keep in mind that the attacks on Iraq benefitted also from a whole slew of technologies, such as satellite mapping and GPS. And the Allies in Desert Storm also had the benefit of information from Kuwaitis who were intimately familiar with Iraq (since that is where Kuwaitis traditionally went to drink alcohol and watch dancing girls).

p. 456: “Of the forty-nine F-117 bombing attacks [on the Jan. 17 1991 initial attack], intelligence reported twenty-seven hits.”

If only 55% of bombs landed on target with 1990s technology, what would have been the likely success rate in 1941?

The Germans seemed to carry it off.

I suspect they were much m ore inventive than we were. We were lucky that Hitler was not as smart as his army.

The ME 262 a year earlier might have made Normandy impossible.

@Rich,

“On a related topic: I saw an article a few years ago on how failures in armed service operational procedures and doctrines were discovered in the field, where fixes were put into service. Then at the end of the war, the field organizations which had implemented the fixes were demobilized. But those fixes often had never been incorporated into the official manuals, so a later generation of users had to discover them again.

This is a meta-failure, which continues to this day.”

Here’s an example of this precise point: During the recent campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, we discovered a need to have what became termed a “Personal Security Detachment” for the senior leaders at and above battalion level, in order to enable them to actually circulate on the battlefield. These PSD elements wound up being taken out of hide from subordinate units, to the tune of about a maneuver squad’s equipment and personnel from each line company. These ad-hoc elements were usually consolidated and worked out of the various Headquarters companies at battalion and brigade level.

They’re an operational necessity, or your commanders are going to wind up being held prisoner in the command posts, no matter what. You cannot count on being able to circulate on the battlefield in today’s highly lethal rear areas, mainly because the linear battlefield with front lines and safe areas is pretty much an artifact of history, likely never again to be seen.

And, what have we done, having learned this? Oh, well… Of course, we’ll never need to have these elements again, so upon return to home station and garrison mode, we shut them down, and there is not the slightest sign that the Army or Marine Corps sees a need to create permanent security detachments in the Headquarters to ensure that the commanders can get out and do their jobs on the battlefield. So, next time we go trundling off to war, we’re gonna have to throw these elements together again, strip the line units of assets they need, and re-invent the wheel all over again.

Oh, and they are also going with the fantasy that mine-protected vehicles aren’t going to be the minimum standard, going forward. Supposedly, we’re not going to need any kind of armored logistics support equipment in the rear areas, so we’re surplusing a lot of MRAP assets and up-armor kits for the wheeled vehicles, as well.

As one of my South African/Aussie acquaintances who was an MRAP logistics guy put it: “Fookin’ genius, mate…”.

Biggest part of the problem is that the structural straight-jacket we have in the American armed forces results in an inability to adapt to conditions as they are; the loggies don’t want to fight, and the combatants don’t want to have to worry about logistics. Because of that, well… Idiocy abounds.

Case in point, one that I think I may have raised before on this site: If you go back and look at a lot of the action in the Iraqi theater of operations, there was a huge disconnect in that we’d have our maneuver guys–Infantry, armor, and the like–Wandering around the area of operations on intelligence-based efforts to find and fix the enemy in place for destruction. Thing was, they’d never quite pull it off–The enemy rarely cooperated, and the usual result of these missions were innumerable dry holes. Meanwhile, every goddamn night, the logistics convoys would be getting hit with ambushes of all sorts, ranging from harassing small arms fire to full-scale complex IED attacks. And, those logistics guys would respond by blowing through the contact, and then (maybe… They often didn’t bother…) reporting it to whoever was in command in that sector. Since the loggies worked for CENTCOM out of Baghdad, they felt no part of the fight, and did not feel any need to participate in the combat mission of finding and destroying the enemy. To a large degree, the loggies were really running a finishing school for the insurgents…

So, what was nuts about that? The entire mentality. In a counter-insurgency, each and every contact is like gold; you have to engage and destroy the enemy whenever they raise their heads, and utterly destroy them. You cannot say “Oh, that’s a job for the infantry outfits…”, and blow through the contact at 50mph. That ambush force is going to evaporate the minute you’re out of range, and dissolve into the countryside, getting together to hit you again the next time. You want to solve the problem permanently, you need to follow up each and every contact by fixing them in place, and then annihilating them. This means, sadly, that the loggies are gonna have to take up the role of being the combatants, because they’re the only ones who’re getting the contacts necessary to generate casualties on the other side.

But, because we’re so pipelined, loggies say “Combat ain’t our job…”, and the combat guys say “Logistics security isn’t ours, either…”. Which results in nobody really being effective at eliminating the enemy… It’s almost like having convoy operations in WWII operate in a vacuum, with the escorts out looking for subs independently, and just letting the cargo ships operate on their own.

To fix it all, I’d say that the entire paradigm needs to be broken. Utterly. No more branches, no more specialties, no more insular little communities built around special jobs or missions–If you’re in uniform, then you’re there to fight, and if the enemy raises his damn head and attacks you, you need to engage and destroy him utterly, whenever and wherever that might be. Your first job must be to engage and destroy that enemy, and whatever other mission you also have, that’s secondary.

Properly done, the enemy really ought to be more terrified of engaging our troops doing logistics work, because those would have to become our most experienced career soldiers, who got to those positions via a lengthy apprenticeship in the combat arms.

Of course, our current lot of time-serving hacks will never do something like that, so we’re going to continue on with the maladaptive behavior.

Biggest part of the problem is that the structural straight-jacket we have in the American armed forces results in an inability to adapt to conditions as they are; the loggies don’t want to fight, and the combatants don’t want to have to worry about logistics. Because of that, well”¦ Idiocy abounds

I’m concerned about the quality of officer cops types with the PC and “diversity” rules as they are.

I can’t forget about the the letter from the West Point instructor.

It’s obvious reading between his lines who the problem cadets are.

However, during my time on the West Point faculty (2006-2009 and again from 2013-2017), I personally witnessed a series of fundamental changes at West Point that have eroded it to the point where I question whether the institution should even remain open. The recent coverage of 2LT Spenser Rapone – an avowed Communist and sworn enemy of the United States – dramatically highlighted this disturbing trend. Given my recent tenure on the West Point faculty and my direct interactions with Rapone, his “mentors,” and with the Academy’s leadership, I believe I can shed light on how someone like Rapone could possibly graduate.

And:

l was unfortunate enough to experience this first hand during my first tour on the faculty, when the Commandant of Cadets called my office phone and proceeded to berate me in the most vulgar and obscene language for over ten minutes because I had reported a cadet who lied to me and then asked if “we could just drop it.” Of course, I was duty bound to report the cadet’s violation, and I did. During the course of the berating I received from the Commandant, I never actually found out why he was so angry. It seemed that he was simply irritated that the institution was having to deal with the case, and that it was my fault it even existed. At the honor hearing the next day, I ended up being the one on trial as my character and reputation were dragged through the mud by the cadet and her civilian attorney while I sat on the witness stand

She was not disciplined and graduated. God help the troops she commands.

The officer corps has always had issues; West Point has never been the best source of officers, either.

Like I said, though–The whole paradigm is broken, top to bottom, side to side. Recruitment, NCO selection, officer selection, retention… All of it.

The wrong people get recruited for the officer accession system, the enlisted system, and all the rest flows from there. Most of our problems boil down to one thing, and one thing only: We don’t select the right people, and the ones we do select are not properly trained, utilized, or retained.

We’re still using a personnel system that was first kludged together back around the turn of the 19th Century; the whole idea of how we recruit and train is still based on the thrown-together hodge-podge that we had to graft on top of the Depression-era Army/Navy system of carefully selected volunteers, and we’ve never stopped since to examine the basic assumptions underlying most of what we do.

Case in point–Why the hell do we maintain this massive bureaucratic training base that we built to train a mass conscription Army and Navy for WWII? The entire mentality amounts to the factory processing of draftees, slightly modified to deal with the volunteer system. Today’s commander has zero control over who he gets out of the personnel pipeline, how they’re trained, and/or what they’re trained in. If a company commander out in the hinterlands of the Army, like Joint Base Lewis-McChord, gets hit with a new mission like doing route clearance, he’s supposed to just pull that out of his ass and use the same product of the basic training and advanced individual training system that the rest of the Army’s Combat Engineers gets. Why? Wouldn’t it be a lot smarter for the system to have that company commander get total control over every aspect of his unit, to include doing the individual training his men will need? Wouldn’t that give us units with much tighter control over the quality of training, and enhance unit cohesion/morale?

Why are we still operating these huge, impersonal, slow-to-react institutional training structures that eat up a huge swathe of our experienced enlisted personnel? Wouldn’t it be smarter to put those guys out in the line units, to fill all the slots we need filled, instead of having them spend years doing Drill Sergeant training?

Hell, for that matter, why the hell do we spend millions (literally–Add up what it costs just to get a guy to an experience level where he’s an effective junior NCO, in terms of training exercises and the like… It’s gonna add up to millions more than just his salary…) of dollars to train an NCO, and then throw his ass out to be a recruiter in the middle of his career, when the set of skills he has as an NCO don’t do a damn thing to help him be an effective recruiter? Not to mention, the hit he takes having having several years of time in the middle of his career effectively sidetracked into irrelevancy… What point does recruiting duty serve, when it comes to making better NCOs? Absolutely none, and that job ought to be filled some other way.

So much of what we do hasn’t been looked at–The retirement system, for example: Why the hell do we do what we do? Wouldn’t it be a lot smarter and cheaper to transition soldiers directly into DOD or other civilian government jobs, where they’d earn salaries as opposed to a retirement check? Why don’t we look at having guys do as much time as their bodies can stand on active military duty, and then transition them over to do other government jobs, as opposed to doing an immediate military retirement? Wouldn’t it make a lot more sense to say “Hey, you’re done doing your active duty military time, now go be a National Forest Service employee until you retire…”. While you’re at it, change the whole retirement system so that instead of a fixed-sum deal, it’s a portable 401k plan or something else that you take with you after even a short-term active duty contract.

Nearly everything we do is a legacy of some kludge we did years ago, and which was done because of conditions that haven’t existed since the late 19th Century. It’s way past time we stopped what we’re doing, re-examined how we are doing it, and came up with some blank-sheet improvements.

Gavin,

Regards this —

>> As a dilettante, let me pass on an example of the kind of snippet that leads me to suspect that bombing accuracy (really, inaccuracy) was the key factor in the Allies morally-challenging decision in both the European and Japanese theaters to switch from targeting industrial facilities & infrastructure to burning down cities & their inhabitants.

Your thoughts here are absolutely right, with no argument.

American “Bombing Through Overcast” from late winter 1943 to April 1945 using radar or radio beacons was area bombing, period, full stop.

The circular error probability of radar bombing was two miles when there were no “gross errors” in navigation. Which happened a low double amount of the time.

The combat box formations of the 8th & 15th AF in this period used 36 to 54 bombers. If each bomber carried 12 each 500-lb bombs with an interval-o-meter setting of 400 feet between bombs. That meant a pattern of between 432 to 648 500-lb bombs in a string 4,400 feet long and as wide as the combat box.

This covered over one square mile of territory on the ground.

General Doolittle said after the war that the RAF Bomber Command “Did precision bombing of area targets” while the USAAF “Did area bombing of precision targets.”

Kirk: The US military is, among other things, perhaps the world’s biggest bureaucracy and political slush fund. Which isn’t ideal, if the point is to maximize military efficiency. But that’s not the only concern. One good thing about the current system is that the enlisted men don’t idolize the officers, but look at them with a sort of benign, low-level but ever present contempt. Tightening the inter-group bonds in ways you suggest may not actually outweigh the benefits, when thinking about the potential social effects, given our distinctly unhealthy political climate.

Kirk,

This —

>>Where the problem lay was in the system and hierarchy itself–There was nothing to be lost by continuing to bet on the primacy of conventional military operations before WWI, and so, the men forecasting the impact of the machine gun and so forth were seen as risky bets by those who made the decisions.

As someone who “lives inside the train wreck” known as American military procurement, I’m here to tell you that your diagnosis is spot on…but incomplete with regards to the pernicious impact of a -LACK- of institutional memory on military affairs.

I’ve seen it during the early 2000’s in my agency when we had a massive military procurement expansion after 9/11/2001 with a declining procurement work force to administer it because the Dubya Administration and Sec. Def. Rumsfeld in particular planned to fight a “short victorious war”.

The issue of the USAAF’s 500-lb bomb going into WW2 was in that ‘-LACK- of institutional memory’ lane. It is a long complicated story that started in 1926 when the ACTS/Air Corps crowd decided the 500-lb bomb was perfect for factory destruction because a long fall from high altitude would result in a “explosive tamping effect” making the bomb 4.5 times more powerful than if it was dropped at low altitude.

There was no such tamping effect in this application, but optimizing for 500-lb bomb carriage made it into the YB-17 design specs anyway. (The guy that said this pulled it out of his “x-minus” as a part of the Pursuit vs Bombardment Versus Attack debates of the late 1920’s on which aircraft tract would be best to get an independent air force.)

From then on, optimizing for 500-lb bombs was all about “cut and paste” from one bomber specification to the next.

The issue with why that happened and -STUCK- was in 1926 the US Army Air Corps wasn’t a real military institution.

It was a personnel list of 1,000 pilot officers spread over the 45 contiguous states, the territories of Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico and the overseas Army garrisons of Panama and the Philippines.

This state lasted through out the entire 1918-1941 period.

For example, when the war came in December 1941, there was a total of five guys at Wright Fields (later Wright-Patterson AFB) that made up the total test establishment of the USAAF. This was basically a desk officer and four pilots.

There is a sweet spot in bureaucratic size where you have institutional memory and you are still small enough to listen to outside input, if you have the right accountability incentives.

However, the first thing that usually happens after a war is the “right sized” bureaucracy does all it can to grow and avoid accountability over time.

Such are the incentives of parasitism vis-Ã -vis military bureaucracy.

You probably know of this book already, but I found it interesting Beneficial Bombing by Mark Clodfelter of the National War College about the progressive roots of the Air Force and strategic bombing. Here he argues how public pressure was forcing them to bomb anything and everything in order to expedite the war’s end.

Moreover, the longer the war progressed, the louder the clamor grew to end it, and the closer Spaatz’s targets crept to residential districts in German cities. Both Dresden’s marshalling yard and the rail junction selected for the 14 February attack were less than a mile from the heart of the cities residential area. Even with the Norden bombsight in excellent weather, bomber crews were certain to hit more than just their aiming point; using radar against a “precision” target in the midst of a city guaranteed many civilian deaths. Indeed, the “last resort” target for the 14 February Dresden mission was: “Any military objective definitely identified as being in Germany and east of the current bomb line.” By February 1945 the impetus to end the war quickly provided few limits to the definition of “military objective.”

Then there was the bombing of Berlin also in February. Doolittle asked if they should go after other “definitely military targets” on the outskirts if too much cloud cover over the primary target of an oil installation. Spaatz gave him the order, “Hit oil if visual assured; otherwise, Berlin – center of city.”

There was no doubt what the objective was supposed to be, clouds or no clouds.

Moreover, the longer the war progressed, the louder the clamor grew to end it,

I’ve read Pogue’s biography of Marshall, all four volumes.

First, at the beginning of the war, Marshall had a “little black book” he had been accumulating since Infantry School in the 1920s. In it he had kept track of promising officers. The first year of the war, he spent getting rid of ineffective officers, from general on down.

Second, there was a serious manpower crisis at the time of the Battle of the Bulge. The public was convinced the war was almost over and there was serious resistance to the draft at the time., The resistance was form Congress and the public. Eisenhower went through the rear echelon troops in Europe and sent hundreds into combat units. JCH Lee had built an enormous Service of Supply bureaucracy in Paris.

The technological costs were high, also. The B 29 project costa more than the atomic bomb.

@Trent Telenko,

“The issue of the USAAF’s 500-lb bomb going into WW2 was in that ‘-LACK- of institutional memory’ lane. It is a long complicated story that started in 1926 when the ACTS/Air Corps crowd decided the 500-lb bomb was perfect for factory destruction because a long fall from high altitude would result in a “explosive tamping effect” making the bomb 4.5 times more powerful than if it was dropped at low altitude.”

The lack of what you’re terming “institutional memory” here is endemic to the US military, across the board. There’s also an institutional arrogance that prevents learning from others, and which makes it difficult to admit that we might have gotten something wrong.

I could recite case after case where this has happened, going from procurement through to operational realization of doctrine and purchases. The root of the problem stems from the essential ahistorical nature of our armed forces–We talk a lot about “lessons learned”, but we never actually seem to learn those lessons, or apply them.

There was a British Army exchange NCO that I got to work with back during the 1990s, and one of the things he imparted to me was the opinion that the Army had fundamentally mis-named one of its supposed crown jewels, namely the “Center for Army Lessons Learned”, or CALL. As that Brit put it, and I paraphrase–“…you can’t call it a “center for lessons learned” if you never actually learn the lesson or implement a fix; what you properly ought to be calling it is the “Center for Army Lessons Identified and then Bloody Well Ignored…”.

I am chagrined to have to admit that the man had a point.