In the press of events related to the Great Wuhan Coronavirus Pandemic, many anniversaries of the Second World War have been passing by with little notice and less comment. For example, April 1st 2020 was the 75th Anniversary of the April 1st 1945 “Love-Day” landings on the western shores of Okinawa.

The Okinawa campaign in WW2 has often been described as marking the end old style total war. Where “cork screw and blow torch” close combat to the death between American attackers “who fought to live” and Japanese defenders who “died in order to fight” played out its last dance.

Upon closer examination, as this 75th anniversary article series will demonstrate, Okinawa is far better described as a high tech war for the electromagnetic spectrum between technological peer competitors air and naval forces. A “secret radar war,” if you will, where two opposing command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I) sensor networks were directing land, sea and air forces in a series of both combat and logistical moves and countermoves.

And while the less advanced, and organizationally deficient, Japanese military lost Okinawa proper. It still took advantage of the primarily US Navy institutional biases, American military inter-service rivalries, logistical planning weaknesses caused by that rivalry and US Navy’s unwillingness to learn from “non-approved” sources to never the less defeat the US Navy’s original Phase III plan to overrun the upper Ryukyu’s and install island air and radar bases close enough Kyushu to properly provide land based air superiority for the invasion of Japan.

These campaign objective failures were hidden in tales of US Navy destroyer picket heroism in the “Fleet That Came to Stay:…and classified top secret files…because of the coming budget war associated with the pending merger of the War and Navy department’s into the Department of Defense. After 75 years, this series will part the curtains on these hidden histories.

Too accomplish that objective, this series will examine the planned goals of the Operation Iceberg campaign against what was accomplished. How various American military institutions, doctrine and planning failed. And why the defeat of the US Navy’s Phase III plans set the stage for an American blood bath of preventable naval casualties during the planned Operation Olympic assault of the Japanese home islands, had the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not made the invasion of Japan unnecessary.

OPERATION ICEBERG & THE FORGOTTEN PHASE III INVASION PLANS

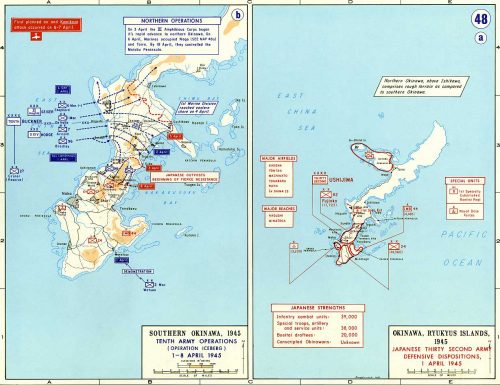

The planning for the invasion of Okinawa with Operation Iceberg, to replace the invasion of Formosa with Operation Causeway, began in September 1944 after the Joint Chiefs directed General MacArthur to by bass Mindanao for Leyte and Admiral Nimitz on September 15th. It also involved October 1944 conferences with the War Department logistical officers to remove a massive removal of materials from the Operation Causeway plan and make way for Phases I, II & III of Operation Iceberg. [1]

Per page 40 of “PARTICIPATION IN THE OKINAWA OPERATION BY THE UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS, APRIL – JUNE 1945, VOLUME 1” Operation Iceberg’s planned Phase III campaign were sub-divided into five separate operations to support the deployment of land based air power to the Ryukyu’s as follows:

(1) The first operation (IIIa) called for the occupation of Okino Daito Jima, code named THREADWORN. [2] This small island to the east or Okinawa was to be established as a LORAN station. LORAN was a ground based functional equivalent of today’s global positioning system radio navigation system. This preliminary operation was cancelled without replacement and the LORAN station was set up on Okinawa. [3]

(2) The objective of the second operation (IIIb) was the capture of Kume Jima, code named KNOWLEDGE. It was to be developed as an airfield for two B-29 bomber wings. This operation was cancelled and then revived as a radar outpost and revised to something approaching the original plan. [4]

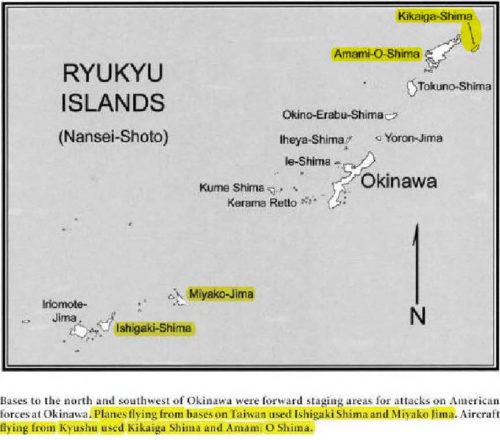

(3) The third operation (IIIc) had for its objective the capture of Miyako Jima, code named ADJUTANT, and its development as an additional air base and southern outpost of Okinawa. A USMC Corps of three divisions was designated as the assault force for this operation. One Marine division was to remain garrison until relieved by a redeployed Army division. The balance or the garrison force was to consist of four anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) gun (90mm) battalions, four AAA automatic weapons (40mm and .50 caliber) battalions, and three 155mm coast artillery gun battalions. The air force garrison was to include two Marine fighter groups (six squadrons of 24 fighters), one night fighter squadron (Marine), one navy torpedo bomber squadron, and two B-29 wings. The RAF Tiger Force of 10 squadrons of Lancaster bombers was to be based there as well. Tentatively, the Vth Marine Amphibious Corps to be used here. However, the blood bath at Iwo Jima made that impossible. [5]

(4) In operation (IIId) forces were to seize Kikaiga Jima, code named FRICTION, which was necessary as an additional air base and northern outpost for Okinawa.

The assault force was to consist of one reinforced Army division; the garrison force: one division, two AAA gun battalions, three AAA AW battalions, and two 155mm coast artillery gun battalions. The air force garrison was to comprise four fighter groups, two night fighter squadrons, and one Navy torpedo bomber squadron. This was the last Phase III operation cancelled. [6]

(5) The fifth and final operation (IIIe) called for the capture of Tokuno Jima. code named ADJOURN, with an assault force of one reinforced infantry division. The purpose of this operation was to establish additional airfields to the north or Okinawa for Naval air units. It was cancelled for logistical reasons in May 1945. [7]

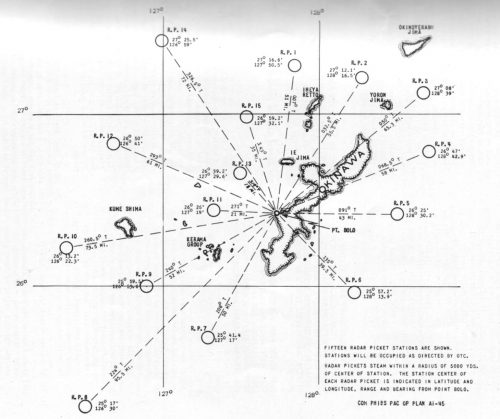

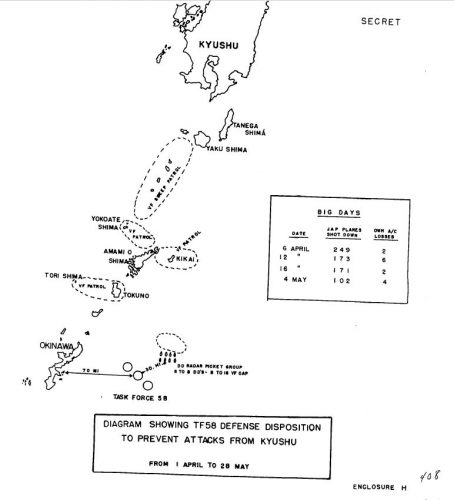

THE UNTOLD STORY OF AMERICAN & JAPANESE RADAR AT OKINAWA

While the story of American destroyer radar pickets at Okinawa is well publicized, exactly how the system of pickets really worked isn’t. Nor is the story of how rest of the US Carrier Fleet supported the Okinawa pickets while protecting the supporting carrier known, either. Below are maps showing the Okinawa radar picket “standard narrative” and TF58’s lessor known defensive dispositions.

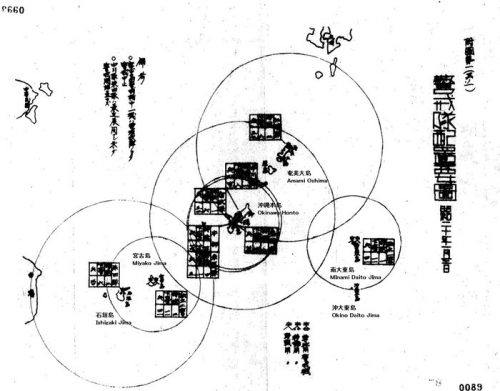

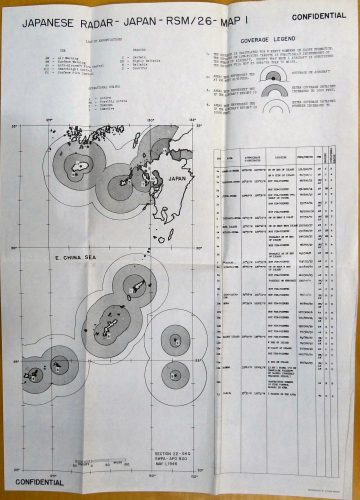

The role Japanese ground based and aerial radars is, frankly, nearly unknown in English language sources. The two maps below of Imperial Japanese ground radar sites in the Ryukyu Island Chain were obtained with the assistance of Japanese researchers at the Axis History Forum web site.

Finally, while Admiral Nimitz’s command lacked a separate theater level radar intelligence organization during the Okinawa campaign. The same was not true of General Douglas MacArthur. His Section 22 radar hunting “Ferret” aircraft operated near Okinawa and SWPA theater controlled 7th fleet submarine radar intercept reports were correlated with them to make radar detection coverage by altitude maps of all know Japanese radar sites.

For the purposes of the map above, Section 22 was using know “skin paint” returns from captured Japanese radars plus a small addition based on the enhanced radar returns of Allied Mark III identification friend or foe systems for safety. Since it was know since the fall of 1944 that IFF was being triggered by Japanese radar signals in the IFF system’s automated response bands. [8]

It was US Navy practice to have sections of fighter planes at low altitude over picket destroyers and carriers, at 5,000 feet and 15,000 feet at a minimum with additional fighters immediately above and below the cloud layers. The radar line of sight for a surface ship to an aircraft at 15,000 feet is 200 miles.

It was not until June 1945, after the Okinawa campaign was all but over, that Section 22 discovered via testing that the IJN Type 13 radar at 150 megahertz trigger Allied IFF out to the radar horizon enabling detection ranges on the radar out to 150 miles on this low powered radar. Section 22 Current Statement #327, dated 17 June 1945, saying that fact, was the single most widely distributed current statement of the war. Lt. Col. Rudolph J Ayres, Section 22’s Senior Assistant Director, saw to it that _269_ Allied military organizations involved in fighting Japan around the world were informed to include ever major Australian, New Zealand, Dutch, US and UK military units in the Pacific. [9]

What Section 22’s discovery meant was that many Japanese radars in the Ryukyu’s archipelago (see figures 7 thru 9) were tracking both the Okinawa centered and Task Force 58 centered combat air patrols over US Navy pickets and carriers in near real time for Kamikaze attacks. Yet there is not a single word of this fact in any of Admiral Samuel Morison’s histories of the Okinawa campaign, nor even most immediate post-war secret electronic warfare documents.

That historical narrative adjustment, more than anything else, is the reason for this series.

-END-

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Operational Project for Base Development Phases II and III, ICEBERG (CP-33).

11 February 1945 AG 093.06/17 2 HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES,

PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS, APO 953 in History of Planning Division, ASF. Volume

10.

These are the Operation Iceberg Phase Place-Code Names with associated air facilities planned for off Okinawa proper:

Phase II — Ie Shima – INDISPENSIBLE – 2 Ftr Strip, 2 VLB Strips (15 Feb War Dept LTR)

Phase III A — OKINO DAITO JIMA – THREADWORM — No Air Strips, sea plane base & LORAN station (15 Feb War Dept LTR)

Phase III B — KUME SHIMA – KNOWLEDGE – 2 Ftr Strip, 1 HB Strip (15 Feb War Dept LTR)

Phase III B (alt) — OKINO ERABU SHIMA – ACQUAINT – 2 Ftr Strip, 1 HB Strip (15 Feb 1945 tactical study 10th Army)

Phase III C — MIYAKO JIMA – ADJUTANT – 2 Ftr Strip, 1 HB Strip (A-Day planned as L Plus 90) (15 Feb War Dept LTR)

Phase III D — KIKAIGA SHIMA – FRICTION – 2 Ftr Strip, 1 HB Strip (F Day planned as L Plus 120) (15 Feb War Dept LTR),

Phase III E — Tokuno – ADJOURN – 2 Ftr Strip, 1 HB Strip (In place of KNOWLEDGE?) (Not mentioned in 15 Feb War Dept LTR)Note 1: U.S. Army and Navy document used “Jima” and “Shima” near interchangeably.

Note 2: Ftr – fighter plane, HB- Heavy Bomber, VLR – Very Long Range Bomber AKA the B-29

[2] All Operation Iceberg code names from the following:

GLOSSARY OF U.S. NAVAL CODE WORDS

NAVEXOS P-474 (Revised March 1948)

SECOND EDITION

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/USN-NAVEXOS_P-474.html

[3] See the following

THE LORAN CHAINS IN WWII

The U.S. Coast Guard in World War II

By Malcolm F. Willoughby Lieutenant USCGR(T)

Chapter 11 – The Story of LORAN

http://www.jproc.ca/hyperbolic/lora_ww2chains.html

and see also

Spaatz Papers Box 41

Incoming Cable

3 Aug 1945

Page 177 of 217

19. Subject: loran Installation , Parece Vela

From CinCPAC ADV HQ

To: ComMarianas 311337Z

Info CinCPOA PEARL HQ, Iscom Guam, 5th NC Brigade, CG USASTAF,

COAST GUARD DET 203.

Your letter serial 0000101 dtg 17 June refers. Proceed

with installation at Parec Vela in accordance my letter serial

0005660 dtg 22 May. Desire construction be expedited as soon as

possible report progress monthly. (Prim Info – D/Opns)

[4] See the following:

Spaatz Papers Box 41

Cables

page 177 of 217

10 Aug 1945

Discussion notes between Spaatz, LeMay and Doolittle

British Engineers are to build a two-runway 8500 foot VHB Wing airfield for 8th Air Force on Kume Shima.

Two British HB Sqd at Futema 15 Oct 1945. All British squadrons (2 + 8) to move to Yotan by 15 Dec 1945.

[5] See pages 32, 43, 46 & 47 of the following:

Seven Stars: The Okinawa Battle Diaries of Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., and Joseph Stilwell

Edited by Nicholas Evans Sarantakes.

College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

[6] See: Nimitz Grey Book, Red pages,

JUNE [1945] (GCT)

[JUNE] 06 0724

COMGENAAFPOA TO CINCPOA ADV INFO CINCAFPAC, COMGEN TEN, COMGENAAFPOA ADMIN3480.

1. The deferment of FRICTION accents our airdrome requirements to support OLYMPIC Operations.

2. Although IHEYA RETTO and AGUNI-SHIMA were captured largely for radar purposes, it is believed it possible to build airdromes, at least fighter airdromes, on these islands.

3. Request all possibilities, including physical reconnaissance; be explored to determine airfield potentialities of these 2 islands. Request earliest advice of investigation results.

[7] PARTICIPATION IN THE OKINAWA OPERATION BY THE UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES PACIFIC OCEAN AREAS, APRIL – JUNE 1945, VOLUME 1, Page 42, Part 1 – USAFPOA, SECTION V — LONG RANGE PLANNING AND LOGISTICS FOR OKINAWA OPERATION, paragraph A. PLANNING, sub-paragraph paragraph 2. d.

[8] Section 22 Current Statement #200, Oct 7 1944, Jap IFF Triggering – Found in ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVAL WARFARE REVIEW Nov-1944 A.C.B 0245/44 910, TRAINING AND STAFF REQUIREMENTS DIVISION, NAVY OFFICE, MELBOURNE

[9] Section 22 Current Statement #327, dated 17 June 1945, Distribution”A” list, found in Australian national archive location MP1049/5 2037/7/1117

Almost all of what I know about the Okinawa campaign is from Sledges’ book.

I’ve been reading this series with great interest ”” thank you very much for doing it!

One radar-related matter I have seen mentioned only occasionally is that the Japanese use of their “stick-fabric-and-wire” training planes for kamikaze attacks was an early example of stealth aircraft. Most accounts simply dismiss them as desperate, last-gasp efforts; desperate they certainly were, but a training plane’s visibility to American radar was less than an all-metal Zero (for example), coming only from the engine, bomb, and perhaps gas tank if the radar beam penetrated the skin of the training plane.

If you have covered this issue in the series, I missed it and would appreciate knowing where it appeared.

Trent: have you ever posted a list of reading material on the Pacific War, preferably focussed on material for laymen? I read lots of stuff in the 70s/80s, like Time/Life stuff, but would not know where to start now. Looks on amazon like there are multivolume series both wrapping up and starting, but those things can really vary in quality.

Thanks for this, Trent. Very interesting.

The old saying is that ‘No plan survives contact with the enemy’. Perhaps there should be nothing surprising about the failure of US forces to accomplish some of the original objectives of the plan — but they should be honored for adapting, improvising, and overcoming. As opposed, say, to German World War I command sticking rigidly to the Schlieffen Plan.

It is easy for us to forget how limited some of the technologies we take for granted today were back during WWII. For example, the devastation of Admiral Halsey’s fleet in a typhoon off the Philippines, because of the lack of adequate weather forecasting capabilities.

Thanks, Trent.

Thanks Trent. I read it all. I have an alternate history book on the Pacific campaign. It is titled, “Rising Sun Victorious”

Pretty interesting.

Mike K, I have read a number of Peter Tsouras’s alternate histories. Good reads.

I really enjoyed reading this. I hope you continue with the installments. I read this and thought it was really interesting as well, similar in that it talked about WW2 in terms that made it directly relate to problems faced today also

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2020/03/how-analog-computational-power-shaped-naval-battles-in-both-world-wars/

Don’t know how accurate it was about Lyete, however. I second Brian’s request for book recommendations. Thanks again!

Joe,

It wasn’t just HIJM Atago’s plot that was special. She had the best trained and longest serving radar crew in the Japanese fleet. Contrary to the Combinedfleet.com’s tabular record of movement for the ship states. She was outfitted with the Type 22 10 CM/3Ghz radar in December 1942/January 1943 at the behest of Commander Yoshiro Sakura, the Communications Officer of the 1st Fleet (Who had been present at the tests of the Mark 2 Model 2, AKA Type 22 radar).

He got his superiors to approve the installation of the Type 22 on HIJMS Atago after she was damaged at Guadalcanal in Nov. 1942 and was undergoing repairs at the Kure Naval Arsenal in Japan. In addition to the radar, Commander Yoshiro Sakuraalso also saw to it that HIJM Atago had the best trained non-commissioned officer radar crew in the fleet to deal with the then still experimental radar.**

[**See pages 57 & 58 of Yasuzo Nakagawa’s “Japanese Radar and Related Weapons of World War II”]

That made Atago’s Captain Nakaoka Nobuki the equivalent of the US Navy’s Adm “Ching” Lee in terms of radar use. This showed up when Captain Nakaoka’s Type 22 10 CM/3Ghz radar on HIJMS Atago was watching when 97 planes from the carriers USS Saratoga and Princeton came out of the low level radar gap to the north of Rabaul Harbor that General MacArthur’s Section 22 radar intelligence boffins had both spotted and plotted for the raid.

This is why all the IJN cruiser’s at Rabaul during the 5 Nov 1943 battle had their boilers hot, their anti-aircraft stations fully manned and some were moving when USS Saratoga and Princeton’s raid came in. They has 10 minutes warning from Atago’s radar because while the USN air raid fleet too low for Japanese land based meter band radars around Rabaul. The 10 CM set staring into that gap could see the raid just fine.

This foresight did not save Captain Nakaoka Nobuki’s life, he lost it in that attack, but it did prevent a real “reverse Pearl Harbor” in Rabaul. It wasn’t just orders by Halsey that every IJN cruiser in the force be struck that prevented any sinkings in the USN carrier strike. The IJN’s readiness had a whole hell of a lot of responsibility for that outcome.

Atago’s next commander, Captain Araki Tsutau, expanded upon the previous captain’s patrimony and integrated the Type 22’s range and azimuth spotting capability into the ship’s optical gunnery so successfully that the method was copied by both the Yamato class battleship’s. This was made clear in several passages on Yamato’s radar gunnery training in Adm Ugaki’s diaries published in “Faded Victory.”

This is why the Yamato was so much more effective as a gun platform at Leyte Gulf than any other Japanese warship in the Battle of Samar.

The death versus the survival of the HIJMS Atago from USS Darter & Dace’s wolf pack attack was the measure of survival for Taffy 3.

Trent,

Thanks, always more layers to the onion. So with the Atago and Type 22,Kurita would have known those were light carriers. You’re writing a book, I hope.

Possibly, even likely, her crew had seen IJN fleet carriers on radar.. Section 22 also captured a document that Atago had radar intercept receivers before or just after it got radar that was used to spot USN cruisers by their electronic foot print.

Thanks Trent!

Fascinating stuff, do you have any idea when you are doing next article?

In reference to the islands in the Ryukyu chain that hosted Japanese air bases. That were used as staging areas for kamikaze, visual spotter and radar snooper aircraft and never fully suppressed by American or British carrier air strikes.

Were these within range of naval gunfire? If so, was there a missed opportunity to bombard them and radar stations, especially with battleships?

I always thought Japan misused battleships early. Could have been better to send battleships vs. Midway, rather than fatally split carrier air between that island and U.S. carriers.

And at Guadalcanal, the Oct. battleship bombardment caused much more damage than any air attack, AFAIK. If Japan had made more battleship attacks it might have made a difference.

Perhaps Allies misused battleships in Op Iceberg? BTW, the article mentions Phase III. What were the 1st 2 phases?

Figure 3 caption mentions Kikaiga Jima – I assume that is Kikaiga Shima

on map. Typo or alternative ways to translate?